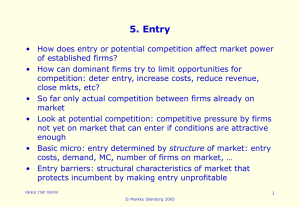

Markku Stenborg Economics of Competition and Antitrust

advertisement

TMP 38E050 Advanced Topics Economics of Competition and Antitrust Markku Stenborg, PhD (Penn State) • Currently at Bank of Finland, Research Dept • April 1st at Ministry of Finance, Economics Dept – Consultant at CEA – Previously: Assistant Prof, Turku Business School; Senior Adviser, Finnish Competition Authority; Senior Manager, KPMG Transaction Services; Research Fellow, ETLA – Docent of Law and Economics, University of Joensuu Course homepage www.cea.fi/hkkk.htm (soon) HKKK TMP 38E050 1 © Markku Stenborg 2005 • This course coversof theoretical and empirical issues related to Economics Competition and Antitrust competition policy such as – Market definition – Market power – Mergers – Coordination of market conduct – Predation – IPRs and high technology • We shall also review some economics of competition strategy relevant for analyzing competition policy • Textbook – Motta (2004) Competition Policy, Cambridge UP – Recent articles – Slides, articles and some notes will appear on homepage HKKK TMP 38E050 2 © Markku Stenborg 2005 • I assume you master Intermediate Micro, Managerial Econ, IO Economics or similar, including related basic Game such as of Competition andTheory Antitrust Nash Equil, and understand basic Econometrics • Grade will be based on – Assignment • Competition Law case, will be handed out during the course • Weight of assignment is one quarter toward final grade, but: • You need to get a passing grade for the assignment to get a passing grade for the course. – Final exam • Four questions, two answers • Expect to have (at least) one applied and one technical question HKKK TMP 38E050 3 © Markku Stenborg 2005 1. Intro: Competition Law and Policy • You should read intro material: Motta, Chaps 1 and 2, Intro from my Lecture Notes, and browse Kovacic & Shapiro and Commissions publications to get feel for competition policy – http://europa.eu.int/comm/competition/ • Why do we need competition law and policy? – Competition promotes efficiency in many activities in society • Efficient: maximize surplus generated by production and exchange, from the asset possessed in society • Allocative efficiency • Productive or X-efficiency • Dynamic efficiency – Market power reduces efficiency and restricts selfguidance of markets HKKK TMP 38E050 4 © Markku Stenborg 2005 – Restraints on competition disturb the market process – Market competition is self-guiding process Goals of competition laws • Promote efficiency? – Yes, but with nonprice competition, simple formulaes (eg. consumer + producer surplus) for efficiency are deceptive and misleading – With non-price competition, customer welfare becomes more multi-dimensional • quality of product, speed and security of supply, introduction of new products and services, etc. • these aspects may not be measurable and value judgments are necessary – Do not strive for perfect competition but promote ”workable competition” HKKK TMP 38E050 5 © Markku Stenborg 2005 • Protect economic freedom and opportunity by promoting competition, so that competition can create – lower prices – better quality – greater choice – more innovation • Sometimes competition laws have also other goals: – In EU, competition laws are used to promote single market within EU – Sometimes competition laws also protect SMEs – These other goals can conflict with the main goal of protecting economic freedom and opportunity HKKK TMP 38E050 6 © Markku Stenborg 2005 Competition Laws 1. Cartels and such Article 81 of EU Treaty statest that […] agreements between undertakings, decisions by associations of undertakings and concerted practices […] which have as their object or effect the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition […] shall be prohibited • Article 81 covers much more than formal cartels • Not only collusion, but also many beneficial forms of horizontal and vertical cooperation are prohibited • In US and many other legislations there are similar paragraphs 2. Monopolization and such Article 82 of EU Treaty states that HKKK TMP 38E050 7 © Markku Stenborg 2005 Any abuse […] of a dominant position […] shall be prohibited […]. Such abuse may, in particular, consist in: – imposing unfair purchase or selling prices or other unfair Competition Laws trading conditions; – limiting production, markets or technical development to the prejudice of consumers; – applying dissimilar conditions to equivalent transactions with other trading parties, thereby placing them at a competitive disadvantage; – making the conclusion of contracts subject to acceptance by the other parties of supplementary obligations which, by their nature or according to commercial usage, have no connection with the subject of such contracts • Per se: conduct is prohibited if it meets the legal test regardless of other issues HKKK TMP 38E050 8 © Markku Stenborg 2005 • Rule of reason: conduct is prohibited if its negative consequenses outweigh the positive • Articles 81 and 82 of EU Treaty are per se prohibitions • But to prove that firm has abused its dominant position, authorities must – show that the firm has dominant position – conduct was abusive – In practice, Article 82 has flavor of rule of reason analysis • In some legal systems, many vertical restraints are dealt with rule of reason – Effects of vertical restraints to competition and efficiency are ambiguous – Many vertical restraints are solutions to problems, not a problems for competition • Vertical restraints can align private incentives in supply and distribution HKKK TMP 38E050 9 © Markku Stenborg 2005 3. Mergers • Transactions that lead to increase in market power or to some other competition problems may be prohibited – Illegal to monopolize markets by M&As • EU: ”A concentration which would significantly impede effective competition […], in particular as a result of the creation or strengthening of a dominant position, shall be declared incompatible” • US:”the effect of such acquisition may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly” – Formely EU had dominance test – Usually SLC-test poses lower threshold for intervention – Here, monopoly is US legal jargon strong market power, dominant position monopoly in Econ textbooks HKKK TMP 38E050 10 © Markku Stenborg 2005 Market Power in Case Law • Read Motta, Ch 2 & 3, Rubinfeld, browse Nevo, and read Volvo/Scania decision, market definition pp 5-21 Assessment of market power in abuse and merger cases 1. Define so-called relevant antitrust markets 2. Evaluate market power within the relevant markets – SCP paradigm • Relevant markets are defined basically by demand substitution – Only those goods that provide immediate and intense competitive constraints to each other belong to the same relevant market – In some instances, also supply substitution and entry by potential competitors are taken into account in market delineation HKKK TMP 38E050 11 © Markku Stenborg 2005 • Market power on relevant markets is analyzed: – calculate market shares Market Power in Case Law – analyze competitive strengths of firms – evaluate degree of actual competitive pressure firm faces – evaluate entry barriers – evaluate supply substitution • In abuse cases, analyze whether conduct of dominant firm was misuse of market power – In EU, dominant firms have special obligations – Dominant firms cannot use their market power to impair conditions of competition – Idea is to protect competition, not competitors • Extra class on Mon. 14.3. at 14 pm, Room A-401 • No class on Thu. 17.3. HKKK TMP 38E050 12 © Markku Stenborg 2005 2. Economics of Market Definition • Read Motta Ch 3 • Why we need to define markets in case law? – Calculate meaningfull market shares • Diet Coke on cola or on beverage markets? BMW on luxury car or vehicle markets, say? – Old SCP idea: market shares tell us something about market power • More on this in Oligopoly and Merger sections – Identify competitors and main competitive constraints – We are interested in market definition only to extent it helps in analyzing market power – Sometimes we can identify and measure market power w/o defining markets • More on this later on HKKK TMP 38E050 13 © Markku Stenborg 2005 How to define markets? — SSNIP • Read Market Definition Guidelines • Market is something that can be monopolized • If it can’t be monopolized, important competitive pressures out of ”candidate market” – Take a small set of substitute goods and geographic area – All produced by hypothetical monopoly – Incentive to permanently increase prices by 5-10 %? – Yes: Candidate market = relevant market • Proceed to analyze market power etc – No: Candidate market < relevant market • Include more goods or geographic areas and repeat • Logic: Goods on relevant market create intense competition to each other HKKK TMP 38E050 14 © Markku Stenborg 2005 to defineismarkets? — SSNIP – OnceHow this competition removed, incentive to increase price – If strong competition remains, price increase is not possible, and goods do not constitute relevant market – Leave out significant constraints on market power, candidate market is too small – Keep in firms and products that are not significant constraints, market is too large • Price increase: – Consumers substitute away – Outside producers increase output or enter • SSNIP asks: how much demand shifts away for a price increase? – SSNIP in economic jargon: What is demand elasticity for this set of goods? HKKK TMP 38E050 15 © Markku Stenborg 2005 • Residual demand curve is the demand curve faced by an How to define markets? — SSNIP individual firm – Residual demand = total market demand curve - supply of all other firms in market – Residual demand curve incorporates effects of changes in prices of other products in response to changes in given product’s price – Residual demand is tool to evaluate relevant market as it is relatively easy to estimate • Homework: How do you derive residual demand? HKKK TMP 38E050 16 © Markku Stenborg 2005 • Marshallian demand based on ceteris paribus assumption and How to define markets? — SSNIP measures effect of price change by keeping all other prices constant – Merger Guidelines assume that “the terms of sale of all other products are held constant” = Marshallian demand – Direct demands are hard to estimate • Suppose condidate for relevant market has n goods and their demand depend on each others prices • Need to estimate at least n2 parameters to get any info on Marshallian demand • Price change in some goods do not leave all other prices constant • Prices and quantities are determined jointly in equilibrium – Can one identify demand and supply? HKKK TMP 38E050 17 © Markku Stenborg 2005 Critical Elasticity of Demand and Critical Loss • SSNIP-test should be applied by estimating own elasticity of demand • What value of elasticity is large enough for concluding that given set of goods comprise relevant market? • P0 = Current price • P1 = P0 plus some specified price increase t • C = Short run marginal cost • L = Current price-cost margin or Lerner-index: (P0 – C)/P0 = 1 – (C/P0) • T = Minimum price increase deemed significant (.05 or .1) T = (P1 – P0)/P0 = (P1/P0) – 1 • e(P) = (dQ/Q)/(dP/P) elasticity of demand HKKK TMP 38E050 18 © Markku Stenborg 2005 • AssumeHow C is constant, profits are then (P-C)Q to define markets? — SSNIP • For profitable price increase, ex post profits must at least equal profits from selling more at lower price • Break-even condition is Q(P0)(P0 – C) = Q(P1)(P1 – C) where P1 = break-even price • Rearranging: Q(P1)/Q(P0) = (P0 – C)/(P1 – C) • Using definitions of T and L: [(P0 – C)/P0]/[(P1 – C)/P1)] = L/(L+T) • For linear demand Q = (A - P)/B: Q(P1)/Q(P0) = (A - P1)/(A – P0) = 1 – [(P1 – P0)/P0][P0/(a – P0)] • Recall elasticity of demand here is e(P0) = P0/(A - P0), which gives Q(P1)/Q(P0) = 1 - Le(P0) HKKK TMP 38E050 19 © Markku Stenborg 2005 How to define markets? — SSNIP • Break-even requires Q(P1)/Q(P0) = L/(L+T) so this gives us L/(M+T) = 1 – Te(P0) and solving gives us critical elasticity e(P0) = 1/(L+T) • When demand is isoelastic, break-even elasticity is e(P0)[log(L+T) – log(L)]/log(1+T) • Critical sales loss for a price increase = proportionate decrease in quantity sold as a result of the price increase large enough to make price increase unprofitable • Sales loss resulting from price P0 P1 is 1 - Q(P1)/Q(P0) HKKK TMP 38E050 20 © Markku Stenborg 2005 How to define markets? — SSNIP • For linear demand Q = (A–P)/B we can write this as 1 – Q(P1)/Q(P0) = 1 – (A – P1)/(A – P0) = [(P1 – P0)/P0][P0/(A – P0)] = Te(P0) • Applying break-even value of e(P0) derived above gives value for break even critical sales loss Y = T/(L+T) • If actual sales-loss after price increase is less than Y, it is profitable to increase prices • The break-even value of the critical sales loss is the same for both linear and isoelastic demand curves • Relationship between market power index L, and critical e and Y for 5 % price increase: L% e Y% 50 1.82 9.1 40 2.22 11.1 30 2.86 14.3 20 4.00 20.0 10 6.67 33.3 HKKK TMP 38E050 21 © Markku Stenborg 2005 Cross-Price Elasticity • Sometimes in case law market definition is based on crossprice elasticity of demand • Cross price elasticity of demand = (dQi/dPj)/(Qi/Pj), where Qi and Pi denote the quantity and price of products i and j • Cross price elasticity = How demand for good i reacts to price increase of good j? • Sounds like nice idea to delineate markets: goods belong to same relevant market if they are good-enough substitutes • i and j are on same market if cross-price elasticity is large enough and otherwise are on different markets • Cross price elasticity is not a good measure for market delineation • Market delineation is not question of how much demand will flow from i to j as Pi increases HKKK TMP 38E050 22 © Markku Stenborg 2005 • Cross-price elasticity is notmarkets? usually symmetric, eij eji How to define — SSNIP • eij: ”i and j on same mkt” and eij: ”i and j on different mkt” is possible • Even if cross price elasticity is small, market need not be narrow, as there may be many other goods that restrict the market power of hypothetical monopolist • If there are many good substitutes, price increase will divert demand to many goods • Then cross price elasticity must be small • Price and cross price elasticities are connected: • Price elasticity = 1 + weighted average of all cross price elasticities • Weight: share of income in relation to share of income of the good in question HKKK TMP 38E050 23 © Markku Stenborg 2005 ”Cellophane Fallacy” • US Supreme Court: high cross price elasticy between cellophane and paper wrapping relevant market wider than cellophane Du Pont not dominant – Also SSNIP test ignores fact that firm may already have market power • Firm with market power wants to increase price to level where competitive constraints start to bite – Demand usually turns more elastic as price increases • Then goods actually outside of relevant market seem to be substitutes • High cross price elasticy indication of use of market power, not an indication of wide market • Cellophane fallacy means that a different approach is required in abuse of dominance cases HKKK TMP 38E050 24 © Markku Stenborg 2005 3. Market Power • Market power = ability to profitably charge P > MC • Sources of market power – Only few firms active in the market – Products are differentiated, and some customers prefer one firm’s product to other • Firm that attempts to ”steal” customers from its competitor must reduce price a lot • Firms have less incentives to lower their prices – Capacity constraints • Firm have less incentive to win more customers – Customers are not informed of all firms’ prices • Incentive to lower price is reduced – Switching costs – 38E050 Cartel or collusion (later in Oligopoly section) HKKK TMP © Markku Stenborg 2005 25 • Market How power to is source of inefficiency define markets? — SSNIP – Allocative inefficiency • Harberger triangle • Rent seeking – X-inefficiency • Less need to control costs or to concentrate on key capabilities • Less need to provide value to customers – Dynamic inefficiency • Less incentive to innovate • Market power allows restrictions on competition – Entry deterrence – Predation – Price squeeze – Cartel or collusion HKKK TMP 38E050 26 © Markku Stenborg 2005 Monopoly’s profit How to maximization define markets? — SSNIP • Assuming constant MC, profit = [P(Q) - C] Q - F • To maximize profits, set d/dQ = 0: d/dQ = P(Q) + Q dP/dQ - C = 0 P*(Q) - C = -Q dP/dQ • Divide both sides by P* (P* - C)/P* = -(Q/P*)(dP/dQ) • Rewrite this as L = 1/e • L = Lerner Index, e = elasticity of market demand • Under perfect competition or perfectly elastic demand: P = C, hence L = 0 • L is measure of market power: 0 < L < 1/e • If we can estimate P, e and C, we can estimate market power L – Not practical HKKK TMP 38E050 27 © Markku Stenborg 2005 Estimation of market power Read Motta Ch 3, browse Nevo (2001) and Slade (2002) Iwata-Breshanan-Lau method • General idea: firms reveal market power through market behavior • In equilibrium, MC = Perceived Marginal Revenue, or – Perfect competition: P = MC – Monopoly: P = MC + Q dP/dQ – In general: P = MC + Q dP/dQ • Then seems to measure market power: 0 < < 1 – Suppose MC stable and demand fluctuates, can we identify from observed data? • = (P-MC)/(Q dP/dQ) • In general: no HKKK TMP 38E050 28 © Markku Stenborg 2005 • • • • • • – DrawHow picture monopoly and assume observed tofor define markets? — only SSNIP data is known: problem Only when demand curve rotates can be identified Firm i chooses qi to maximize P(Q,Z)qi – C(qi,.), where P is market or average price and Z vector of variables that affect demand FOC: pi = MCi – [(Q/qi)(qi/Q)(P/Q)Q] Term (Q/qi)(qi/Q) is Conjectural Variation coefficient – How average firm expects market output will react to changes on its output • This is comparative statics, not dynamics – FOC represents firms supply relationship, not supply curve Suppose demand Q = a0 + a1P + a2ZP + v, v is error term Substituting into FOC yields (1) pi = MCi – P/(a1 + a2Z) + u HKKK TMP 38E050 29 © Markku Stenborg 2005 • (1) canHow be estimated: estimate market — demand, multiply P to define markets? SSNIP by a1 + a2Z, and regress • This works for homogenous goods, eg bank loans • To measure market power with differentiated goods, we need to estimate demand consistently • Basic idea: how well other goods substitute for goods of firm i and constrain her market power? • Answer: elasticity of residual demand – Residual demand does not tell who or what constrains market power • Straight-forward approach is to specify system of demand equations q = D(p;r), where q is J-vector of quantities demanded from J commodities, p is a J-vector of prices, and r is a vector of exogenous variables that shift demand • Need to define D(.) in a way that is both flexible and consistent with economic theory HKKK TMP 38E050 30 © Markku Stenborg 2005 Aside: Residual Demand of for market power • The inverseEstimation demand function firm 1 is (1) P1 = P1(Q1,Q-1,Y;) where P1 and Q1 are price and quantity for firm 1, Q-1 is vector of other firms’ quantities, Y is vector of demand shifters and is vector of parameters • Inverse demand functions for all other relevant products are given by Pj = Pj(Q1,Q-1,Y;) – Notation continues to treat product 1 asymmetrically. • Supply behavior of other firms are marginal cost = perceived marginal revenue (2) (3) MC-1(Q,W,W-1,-1) = PMR-1(Q1,Q-1,Y;,-1), where HKKK TMP 38E050 31 © Markku Stenborg 2005 P j Qi market power Estimation of PMR j Pj i Qi Q j – – – – • W is vector of industry-wide factor prices Wj is vector of firm-specific factor prices j are cost function parameters j are conduct parameters describing conjectures ∂Qi/∂Qj, ie expectations how rivals react to changes in output Solve (3) and (2) for Q-1 and P holding Q1 fixed; solution is (4) Q-1 = F(Q1,Y,W,Wj; ,j,j) • Next substitute (4) into (1) to get the residual demand curve facing firm 1 and simplify: P1 = R(Q1,Y,W,Wj; ,j,j) – This is what we want to estimate HKKK TMP 38E050 32 © Markku Stenborg 2005 Modeling Demand Estimation of market power • Traditionally: Linear Expenditure, Rotterdam, Translog model, and Almost Ideal Demand System (AIDS) • Problem 1: Number of parameters estimated increases with square number of products: 20 firms with 20 brands each 40 000 elasticities with straigth approach • Problem 2: Multicollinearity of prices and need for an instrumental variable for each of them – Equilibrium price and quantity determined jointly by demand and supply schedule – Price increase by i is followed by rivals need to take into account how rivals react residual, not market demand • Problem 3: Simple direct approach ignores heterogeneity among consumers – Next we turn to potential solutions HKKK TMP 38E050 33 © Markku Stenborg 2005 1. Avoid problem Estimation of market power – Focus on aggregate demand • Bank loans – Focus on narrowly defined product • Self service 95 octane – Focus on sub-markets • Particular segment in beer industry • This is enough in some cases 2. Symmetric representative consumer • Constant Elasticity of Substitution (CES) utility function 1/ r r U(q) qi i 1 J where r is a constant that measures substitution across products HKKK TMP 38E050 34 © Markku Stenborg 2005 • Demand of representative consumer obtained from CES is Estimation of market power qk pk1 /(1 r ) J p r /(1 r ) I i i 1 • • • • where I is income of representative consumer Dimensionality problem is solved by imposing symmetry between products Estimation involves a single parameter, regardless of number of products, and can be achieved using simple (non-linear) estimation methods Cross-price elasticities are restricted to be equal, regardless of how “close” the products are in some attribute space This restriction can have important implications and in many cases would lead to wrong conclusions HKKK TMP 38E050 35 © Markku Stenborg 2005 • Symmetry condition is restrictive and for this model implies Estimation of market power qi p j qk p j , for all i, j, k p j qi p j qk Alternative CES specification U(q) J J q q j j 1 j j ln q j j 1 yields Logit demand (more below) – First term suggests consumer will consume only good with highest j – Second is entropy term and expresses variety-seeking behavior • Estimation of this model involves J, not J2, parameters and allows for somewhat richer substitution patterns HKKK TMP 38E050 36 © Markku Stenborg 2005 • Substitution patterns in Logit model are function of market oftomarket power shares only,Estimation and not related product characteristics • Market share here equivalent to quantities consumed by representative consumer • If price of good i increases, consumer is assumed to keep same ratio qj/qk instead of consuming relatively more of products that are similar to product i • Models impose symmetry conditions which implicitly suggest extreme form of ”non-local” (in attribute space) competition • For some industries or cases this model of differentiation is adequate, for most markets this is not 3. Separable utility and multi-stage budgeting • Divide products into smaller groups and allow for flexible functional form within each group HKKK TMP 38E050 37 © Markku Stenborg 2005 • Justification: Separable preferences & multi-stage budgeting • (Additive) Separable preferences: Estimation of market power U(q1,q2, ...,qJ) = v1(q1,q2) + v2(q3,q4) +…+ vG(qJ’,...,qJ) where v1, ..., vG are sub-utility functions associated with separate groups – Groups could be broad categories such as food and wine, and each group can be divided into more sub-groups • Multi-stage budgeting – Consumer allocates expenditure in stages • at highest stage expenditure is allocated to broad groups (food, housing, clothing, transportation…) • at lower stages group expenditure is allocated to subgroups (beer, bread, cheese, ..) … • until expenditures are allocated to individual products (beer i) HKKK TMP 38E050 38 © Markku Stenborg 2005 – At each stage, allocation decision is function of only that group total expenditureof and prices ofpower commodities in that Estimation market group (or price indexes for the sub-groupings) – Cross elasticities between Opel sedan and VW sedan, between Opel van and VW van, and between sedan and van categories, but not between Opel sedan and VW van – Reduces number of parameters to be estimated • Three stage system – Top level: overall demand for the product (cars or beer) – Middle level: demand for different segments (sedan, suv, stw, minivan; or lager, ale, stout, …) – Bottom level: brand demand corresponding to competition between different brands within each segment • Typical application has AIDS at brand level: demand for beer i within segment g in city c at quarter t is HKKK TMP 38E050 39 © Markku Stenborg 2005 sjct = jc + j log(ygct/Pgtc) + kjk log pkct market power ygct is overall where sjct isEstimation share of total of segment expenditure, per capita segment expenditure, Pgct is price index and pkct is price of the kth brand in city c at quarter t • Middle level of demand captures allocation between segments of beer – Often lso modeled using AIDS model – Then demand equation above is used with expenditure shares and prices aggregated to segment level • Top level demand for whole category is log qqct = 0 + 1log yct + 2pct + Zct where qct is overall consumption of beer in city c at quarter t, yct is real income, pct is price index for cereal and Zct are variables that shift demand (eg demographics) HKKK TMP 38E050 40 © Markku Stenborg 2005 4. Discrete Choice Models Estimation power • Model products as bundlesof of market characteristics – sweetness, fiber content, … – alcohol content, bitterness, ... – horsepower, length, ... • Preferences are defined over characteristics space • Each consumers chooses the product with best characteristics for her – use bus if U(bus) > U(car), U(train), U(walk), ... • Discrete choice models yield Logit demands (under some assumptions) – prob that agent n chooses i has logistic distribution • Dimension of characteristics relevant dimension for empirical work, not number of brands • Heterogeneity is modeled and estimated explicitly •HKKKCan be estimated using individual or aggregate market data TMP 38E050 41 © Markku Stenborg 2005 Comparison of market power • Symmetric Estimation average consumer models least adequate for modeling demand for differentiated products – Problem: all goods are assumed to be equally good substitutes • Logit models widely used because they are simple • Multi-level model requires a priori segmentation of market into relatively small groups, which might be hard to define • AIDS assumes all consumers consume all products – For broad categories like food and shelter reasonable – For differentiated products, it is unlikely that all consumers consume all varieties • AIDS is closer to classical estimation methods and neoclassical theory, and more intuitive to understand • Discrete choice models require characteristics of products, are more technical to use, and rely on distributional assumptions functional forms HKKKand TMP 38E050 42 © Markku Stenborg 2005 • Nevo 2001 uses discrete choice models succesfully market powerof cereal in 65 – Panel of Estimation quantities and of prices for 25 brands U.S. cities over 20 quarters, using scanner data – Estimate own price and cross-price demand elasticities – Compute price-cost margins implied by three industry structures: each brand on its own, actual structure of few multi-product firms, and monopoly or collusion – Markups implied by current industry structure and imperfect competition match observed price-cost margins – High margins due to consumers' willingness to pay for favorite brand, and to pricing decisions that take into account substitution between own brands – Margins not due to lack of price competition nor collusion – Market power entirely due to the firms' ability to maintain portfolio of differentiated products and influence perceived product quality through advertising HKKK TMP 38E050 43 © Markku Stenborg 2005