Reader Case Study - About Manchester

advertisement

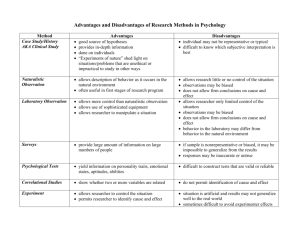

Reader Case Study Abby Schwendeman Professor Victoria Eastman EDUC-301: Corrective Reading Fall 2011 Semester Schwendeman 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS: Phase I: Part A: Reader Background…………………………………………………..…..…… 3 Part B: Assessments …………………………………………………………..…….… 5 Part C: Assessment Database ……………………………………………..…………... 6 Phase II: Administration of Assessments ………………………………………………..………...8 Interpretations of Assessments …………………………………………………………. 9 Plan of Action………………………………………………………………………….. 10 Intervention Lesson #1 ………………………………………………..……….. 11 Intervention Lesson #2 ………………………………………………...……….. 12 Intervention Lesson #3 ……………………………………………...………….. 13 Intervention Lesson #4 ………………………………….……………..…..…… 14 Intervention Lesson #5 ………………………………………………...……….. 15 Parent/Educator Letter (explains Plan of Action)……………………………….……… 16 Kidspiration Software Web/Graphic Organizer ……………………………….….…..…17 Phase III: Evidence of Learning and Reflections on Conducting the Intervention Intervention Lesson #1 ………………………………………………..………...18 Intervention Lesson #2 ……………………………………………..…………...21 Intervention Lesson #3 ……………………………………………..…………...24 Intervention Lesson #4 …………………………………………………………..26 Intervention Lesson #5 …………………………………………………………..30 Phase IV: Impact on Student Learning………………………………………………………..…… 31 Personal Growth as a Reading Teacher……………………………………………..….. 38 References……………………………………………………………………………………… 40 Schwendeman 3 PHASE I: Reader Background Information The subject of this reader case study is a female student in second grade. She lives with both parents and an older female sibling (aged 17). The student enjoys music class, reading and recess, according to a information sheet collected by the teacher at the beginning of the school year. She is not receiving any economic support from the school (i.e. free or reduced lunches) and does not qualify for any special education services at this time. The student does, however, participate in a LLI (Leveled Literacy Instruction) program (similar to reading recovery) four times a week. Her current instructional reading level is 1.7-2.5. According to the Fountas assessment, she is reading “at level.” Fountas and Pinnel level is currently an “H.” The student did attend a summer school program this past summer (before entering second grade) to receive additional support in reading instruction. While she is on the lower end of her grade range, the subject enjoys reading and does so in class and at home with great enthusiasm. The subject appears to be accepted well socially by her peers and does not seem to struggle to make friends. She is kind to others, outgoing and seeks acceptance not only from her peers, but also from authority figures such as teachers and support staff. She is helpful in the classroom and enjoys special attention from teachers. She has expressed a desire to be a teacher in the future. Her parents have given permission for the student to participate in the reader case study, be evaluated/assessed and to receive appropriate interventions. However, the classroom teacher noted, based on her interactions with the family, the subject does not get much support at home and that her family does not particularly value education. The subject often misses school and has an inconsistent attendance record. (The researcher sees this as a potential barrier to Schwendeman 4 completing the reader case study.) While the subject generally completes homework assignments, often they are not done correctly because of her lack of parental guidance and involvement at home. Schwendeman 5 Assessments In talking to the student’s classroom teacher and reading interventionalist, the researcher has decided to focus on the student’s comprehension of text—both fiction and non-fiction. To test comprehension, the researcher proposes using Cloze Procedures and Fountas and Pinnel running records (with corresponding comprehension questions) to record levels and progress monitor throughout intervention lessons/meetings. For consistency’s sake, the researcher anticipates on using Cloze Procedures for both the initial diagnostic assessment and the summative assessment of the conclusion of this study. This will help to show the student’s true progress. The running records should be used throughout the lessons/interventions to monitor student comprehension of self-read passages, as well as working on fluency (which will aide in the student’s overall comprehension). Unfortunately, after completing the first initial screening, the researcher realized that the subject did not have the necessary skills in place to focus on comprehension. It was discussed with the classroom teacher, as well as the researcher’s supervising professor, and determined that the subject needed to focus on phonemic awareness and vocabulary development before trying to focus on comprehension of text. The student needs to be able to decode the text so that they may be able to understand what it is saying. Please see the section entitled “Interpretations of Assessments” for additional information on the changes made to the assessment portion of this case study. Schwendeman 6 Assessment Database Name of Assessment Running Records Rigby [READS] Assessments Grades Appropriate Elementary (K-6) Elementary (K-6) How to Use When to Use Assessment is completed one-on-one with student being tested. Baseline testing should be done at the beginning of school. Anecdotal notes are taken during assessment: errors, insertions, hesitations, substitutions, etc. Computer-based testing to identify instructional reading levels of students Student is given a list of ten provided words to spell. The Monster Test Elementary to Intermediate (K-8) Teacher evaluates what level of spelling student is at based on the spelling patterns present in the student’s answers. Progress assessments should be done every 4-6 weeks depending on needs of students. Information Provided If the selected text is too easy or too difficult Helps identify Instructional Reading Levels Student skill levels in: o Fluency o Comprehension o Accuracy Should be used when identifying reading levels and grouping students in homogeneous leveled groups for reading instruction Instructional Reading Levels Can be used periodically throughout the year to monitor spelling levels and progress in students. Developmental Spelling Level Specific Reading Skill Levels: o Comprehension o Phonics o Vocabulary Information about how the student uses phonics to decode words Reference Information "Running Records Information on Running Records and How to Administer Them." Busy Teacher's Cafe - A K-6 Site for Busy Teachers like You! Web. 02 Oct. 2011. <http://www.busyteachersca fe.com/literacy/running_reco rds.html>. "Rigby Reading Evaluation and Diagnostic System [READS] Intervention." Rigby. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Web. 2 Oct. 2011. <http://rigby.hmhco.com/en/ reads_int.htm>. Gentry, J. Richard. "You Can Analyze Developmental Spelling…” Louisiana.gov. Web. 2 Oct. 2011. <http://sda.doe.louisiana.gov /ResourceFiles/Literacy%20 Assessments/Monster%20Te st.pdf>. Schwendeman 7 Part C: Assessment Database (continued) Name of Assessment Cloze Procedures Accelerated Reader Quizzes Grades Appropriate How to Use Elementary to Intermediate (K-8) Meet one on one with student and provide them with the cloze procedure. Allow student to complete independently for truest individual results. Elementary to Intermediate (K-8) AR Quizzes can be used as part of a reading curriculum or part of a reading incentive program. Generally, it is a school-wide program. When to Use Information Provided If the selected text is too easy or too difficult When checking a student’s comprehension level for a certain text. Helps identify Instructional Reading Levels Student skill levels in: o Fluency o Comprehension o Accuracy Reading Comprehension When checking a student’s comprehension level for a certain text. If the selected text is too easy or too difficult How many books students read throughout the semester Reference Information "Instructional Strategies Online - Cloze Procedure." Online Learning Centre. Web. 10 Oct. 2011. <http://olc.spsd.sk.ca/de/pd/i nstr/strats/cloze/index.html>. “Overview - Accelerated Reader." Renaissance Learning - Advanced Technology for Data-Driven Schools. Web. 10 Dec. 2011. <http://www.renlearn.com/ar /overview/>. Schwendeman 8 PHASE II: Administration of Screening Assessment For an initial screening assessment, the researcher administered a Cloze Procedure to the subject. The researcher chose a first grade leveled procedure that reflected the student’s reading level, rather than choosing a second grade leveled procedure that would have reflected her grade level. However, the subject struggled to read the sentences and seemed to focus so much on decoding and phonics that she was unable to comprehend what she was reading and determine which word was appropriate without assistance and a lot of verbal prompting. To make the assessment have some substance and to prevent the subject from getting discouraged or upset, the researcher assisted the subject in the completion of the task. To do so, the researcher would read the sentence omitting the selected word and then the student would choose from the word bank to complete the sentence. When the subject was still confused, the researcher would then read the sentence with the word choices in it and the subject would “listen for which sounded right.” While the test was not accurate in showing what the student can do individually, it did help the researcher to understand what actually needed to be the focus of the plan of action. Schwendeman 9 Interpretations of Assessments Because the subject was unable to comprehend the text and the task asked of her, due to problems with decoding, the researcher has decided to change the focus of the interventions to help the student build a vocabulary in two ways—segmenting phonemes to break a word into easier pronounceable parts, as well as doing a word study activities with a list of second grade sight words to start working on comprehension (as was previously desired). To help the researcher gain information on the subject’s current level of vocabulary development, another initial assessment will be given to the subject during the first intervention lesson. As a new initial assessment, the researcher plans to use the Yopp-Singer Assessment which requires students to segment words, breaking them into phonemes. For instance, the word “she” would be broken down into two phonemes—“/sh/-/e/”. This helps students decode words because it breaks it into easier pronounceable parts that can then be blended together to form the word. The researcher also plans to use this as the midpoint progress monitoring test and outcome-based assessment for consistency purposes. As additional progress monitoring, the researcher plans to take anecdotal observational notes and collect samples of student work which displays their skills and abilities while working on vocabulary development. Copies of the assessments given to the student, including administration directions, are included in the section entitled “Impact on Student Learning.” Student work can be viewed throughout the section “Evidence of Learning and Reflections on Conducting the Intervention” with the observational notes helping form the reflective paragraphs about each lesson. Schwendeman 10 Plan of Action Lesson Focus Area #1: Segmenting Words Activity/Assessment Initial Screening (Yopp-Singer Assessment) #2: Choosing the Right Word Working on Cloze Procedures with the vocabulary development word list #3: Using Familiar Words in Sentences Midpoint Assessment (Yopp-Singer Assessment) #4: Word Shape: Tall, Small, and Tails Looking at word shapes to help the student visualize the word structure #5: Conclusion/Wrap Up Outcome-based Assessment (Yopp-Singer Assessment) ** The following pages will go into further detail about plans for each intervention lesson, as well as the materials that would be necessary for implementation and duplication of this study. Schwendeman 11 Intervention Lesson #1: Segmenting Words For the initial invention lesson, the researcher plans on administering the new initial screening assessment to help determine the subject’s instructional needs in the focus area of phonemic awareness. The researcher has planned to use the Yopp-Singer assessment which asks students to segment words into individual phonemes. After scoring the student’s assessment and discussing the results with the subject, the researcher will introduce the idea of a vocabulary word study, using a grade-appropriate list of sight words found in a book that was provided by the school’s resource room teacher. The student will become familiar with the words by segmenting them (just as they did on their initial assessment) and reading them aloud to the researcher. The researcher will denote any issues that the student may have with the segmentation or fluid pronunciation of words. If time allows, the student will be allowed to read a book of their choice, using the idea of segmenting phonemes to help decode unfamiliar words. In addition to the observational notes, the researcher would like to incorporate a worksheet (page 1) from the second grade sight word workbook (obtained from the resource room teacher) to help monitor student progress. Schwendeman 12 Intervention Lesson #2: Choosing the Right Word For intervention two, the subject will delve deeper into their vocabulary development while working with words from the aforementioned grade-appropriate sight word list. The subject will check understanding of meanings of the words while completing Cloze Procedurelike activities. The first activity gives the student a sentence with a missing word and requires the student to choose a word from a given list of three choices. The student should be familiar with the meaning of these words, because they are common sight words and have been introduced during the last session; however, should the student need clarification—the researcher will take time to define the words again to assist the student in the activity. The next activity is slightly more difficult, giving the subject a word bank at the top, rather than a smaller and more concise list of choices for each sentence. Adding to the difficulty, this activity also has a sentence that could have two possible answers, so the student will need to complete the others first to see which word actually belongs there. Both activities will encourage critical thinking and the use of context clues to figure out which vocabulary word fits in which sentence. It is the researcher’s hope that the student can work independently on the papers, with minimal guidance, so that the student’s true abilities can be recorded. After the activity, the researcher will discuss answers with the student and correct any mishaps verbally— while leaving the student’s original work on the paper for documentation purposes. Schwendeman 13 Intervention Lesson #3: Using Familiar Words in Sentences In lesson three, the researcher will continue to work with the subject on their word study vocabulary list. In addition to the observational notes, the researcher would like to incorporate a worksheet (page 4) from the second grade sight word workbook to help monitor student progress. This lesson’s worksheet/activity asks students to make the words their own by creating their own sentences that use the words given to them. The activity asks students to create eight sentences, incorporating two given words into each. Not only will the students have to think about the definitions of the vocabulary words, but the subject will also need to think about the relationship that those two words have to each other to successfully write the sentences as asked. While the researcher realizes that the student will probably need help with this activity, because it is the most difficult of all the tasks being asked of the student, the student will be asked to do her best and create her own sentences before asking for help. This activity also has a verbal component to it, because the student will be asked to verbalize their thinking while working on the sentences. This will be a great opportunity for the researcher to model a think aloud and provide guidance to the student, without necessarily just providing the student with the answers. Schwendeman 14 Intervention Lesson #4: Word Shape: Tall, Small, and Tails This activity is unique in that it looks at the physical shape of the letters. While some students may be familiar with this concept—the subject may not be, so it may be important to be able to describe what the activity is asking with specific examples. Students should grasp what the different shapes of the boxes mean (what type of letter—tall, small, or tail—goes in them) and should be able to look for the patterns in the words. Two strategies could be used to accomplish this task. The researcher could take the alphabet and draw boxes around each individual letter to show which letters are “tall”, “small” or “tails”. Similarly, if the student is a visual student—the student could be asked to generate ideas of which letters would fit in each box until they have discovered which type of box each letter of the alphabet goes in. In addition to the observational notes, the researcher would like to incorporate worksheets (page 3) from the second grade sight word workbook to help monitor student progress. For the worksheet itself, the student will again be working on the same vocabulary list that they have used for the last three intervention sessions. The student will be asked to segment the words—and then sort them into the premade boxes based on the shape of the letters. The researcher will provide minimum guidance as necessary. Schwendeman 15 Intervention Lesson #5: Conclusion/Wrap Up For the final meeting with the subject, the researcher plans to administer the outcomebased assessment—the same Yopp-Singer assessment that was given as the initial screening. The subject will also work on vocabulary skills while reading a grade-appropriate book. The researcher has chosen The Paper Bag Princess by Robert Munsch for the student to read because it is humorous and the reader has expressed an interest in “funny books.” It also is slightly above the subject’s independent reading level so it will most likely have words that the subject is not familiar with. The student will not only be asked to summarize the book using the graphic organizer (see page 16), but also will be asked to look for difficult words that they are unfamiliar with and record them. The student will then be guided in using a student dictionary to find the definitions of the words. It is known that the subject is familiar with alphabetizing, so the researcher does not anticipate many difficulties in using an easy-format dictionary. The researcher will then collect the graphic organizer for documentation purposes, along with the Yopp-Singer assessment to be used as the outcome based assessment. Schwendeman 16 Parent/Teacher Letter Explaining Plan of Action Fall/Winter 2011 Dear Educator and Parents, I feel much honored to be able to work with your child/student this semester and hopefully will be able to help her improve her reading skills and confidence. Initially, my target for this intervention was to improve her comprehension—however, after further research and talking with the classroom teacher and my cooperating professor, I have decided to focus on decoding unknown words and vocabulary development. I feel that focusing on vocabulary skills will help build your student’s reading skills (specifically decoding) and therefore will also affect her comprehension in a positive manner. My goal is to make your child/student feel special and give individualized attention that cannot be given to each student in a class as large as this year’s. I want the student to have fun and enjoy working on reading skills, to encourage a love of reading and life-long learning. I myself am an avid reader and I hope to share my love of reading with your child/student! Reading is a life skill that all children need to gain, but can also be a favorite hobby and source of enjoyment for many students. I hope your child/student will share the lessons that we work on together with you, but if she does not or you have additional comments or questions, please do not hesitate to ask me. I am available by phone (574-253-3331) or preferably, email (alschwendeman@spartans.manchester.edu). I look forward to sharing this special time with your child/student and would like to share all that we do with you as well! Thank you again for allowing your child/student’s participation in this study, Abby Schwendeman Schwendeman 17 Kidspiration Software Web/Graphic Organizer WORD: ________________ WORD: ________________ DEFINITION/MEANING: DEFINITION/MEANING: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ __________________________ ______________________ __________________________ ______________________ The Paper Bag Princess WORD: ________________ WORD: ________________ By: Robert Munsch DEFINITION/MEANING: DEFINITION/MEANING: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ __________________________ ______________________ __________________________ ______________________ SUMMARY: Schwendeman 18 PHASE III: Reflection on “Intervention Lesson #1: Segmenting Words” The researcher first had the student complete the Yopp-Singer assessment to check for phonemic awareness, before engaging the student in the vocabulary activity. The student answered without hesitation during the Yopp-Singer assessment and remarked twice that “this is easy!” The reader had great confidence and seemed to enjoy the assessment, although she did appear slightly bored near the end of it. (Twenty-two words are a lot for a second grader to segment!) After the assessment, the student took a short break and got a drink of water. After the student’s break, the student was given a list of sight words that are age appropriate (albeit on the lower level). The researcher asked the student to read the words, segmenting them if needed to help with pronunciation. The student did so with little problems and seemed to be relatively familiar with these words. She noted: “I learned most of these words in first grade!” The researcher then explained that we would be working with these words for the next few days and would be doing a variety of activities with them. The subject expressed excitement about activities and asked if we could play games. The researcher used this to transition into the activity planned for the day. The first section, asking students to fill in the missing letters to form a word from the box, is similar to a game and was presented to the reader as such. The student began to fill in random letters— which did make words, but were not words from the word bank—so there was some correction needed. Overall, the subject did not struggle with this section. The second section, asking the student to choose five words from the box and then create their own sentences, seemed a little overwhelming to the subject. She tried to bargain with the researcher, saying “What if I write TWO sentences?” The researcher was able to verbally Schwendeman 19 encourage the subject and the subject did complete all five sentences. The researcher allowed the students to use their invented spellings because it encouraged the student to use segmentation of phonemes to sound out the words. While most words are not spelled write, when sounded out, they are plausible. The following page displays the worksheet that the subject completed during this lesson. Schwendeman 20 Schwendeman 21 Reflection on “Intervention Lesson #2: Choosing the Right Word” The student was very excited to see the researcher come into the classroom today and was pleased when she was called to work with the researcher independently. Other students seemed jealous, which pleased the subject to no end! The subject seemed in an exceptionally good mood and was definitely ready to work. Again the subject and the researcher reviewed the list of sight words before completing any other activities for the day. The researcher introduced the idea of the activities by working on “our sentence skills” since the reader seemed to struggle with sentence-building during the last session. The subject giggled and seemed to appreciate the extra help. She also expressed enthusiasm when she saw that she did not have to create her own sentences—only having to choose the correct word. She had no problems with the first challenges that she was posed with, choosing the correct word from a list of three potential words, and a short activity dealing with alphabetization (which seemed to just be a placeholder on the worksheet). The subject did however run into an issue with the second activity, in which there was a word bank. One of the sentences (number nine) had two potential answers. She was confused as to which one to put in the blank, because both were plausible answers. The researcher’s suggestion was to skip over that one and answer all the other questions first and then see what word was left to fill in the blank. The subject listened to this advice and was able to see that “play” fit in the sentence, not “come”. Overall, the subject did well with both the activities that she c completed today. It seems that these are common activities for the second grade classroom that she is in. The next activity planned for session three, writing her own sentences again, will definitely stretch her more than these activities. Schwendeman 22 Schwendeman 23 Schwendeman 24 Refection on “Intervention Lesson #3: Using Familiar Words in Sentences” As the researcher suspected, this lesson was MUCH more of a challenge for the subject. The researcher took the subject’s hesitancy as an opportunity to model and did a think aloud for the student. The researcher used one of the easier pairs of words-- “run” and “not” to show how to go about thinking of how these words connected. During part of the think aloud, the researcher said “I’m thinking about how I am not too fond of running. So my sentence could be… maybe… I do not like to run.” This prompted the student to write down the sentence that was generated in the think aloud; however, they did not omit the “maybe” that the researcher had said while buying time during the think aloud. That mistake was discussed with the student, but was left on the worksheet to show what the student did independently. Again, the subject was allowed to use inventive spellings because the researcher wanted her to feel confidence and not get discouraged. The researcher also wanted to see how well the student could independently do the activity. The subject does not have a lot of support at her home, so most often, her homework is completed with no help. The difference between this activity and homework however, was that the researcher then discussed the spellings and mistakes with the student after the activity was over, instead of simply counting them wrong, as they would have been on homework. Schwendeman 25 Schwendeman 26 Reflection on “Intervention Lesson #4: Word Shape: Tall, Small, and Tails” This lesson probably went the best out of all the lessons thus far, which was surprising because it can be difficult for students to understand at times. It should be noted that the student does show strength in mathematical and logical concepts. The subject had also done activities similar to this one, so she knew the basic directions for the activity. She also said “This is like a puzzle! I like puzzles!” The subject required absolutely no guidance or assistance to complete the worksheet. Because the subject finished the planned lesson so quickly, the subject improvised another activity to do with the subject. The subject used a whiteboard and drew boxes of all shapes (tall, small, and tail) and asked the subject to find words that would fit in the box. The researcher made sure not to make the patterns too difficult or complex so that the subject would be able to generate a word that would fit into the boxes. Some of the words that the student came up with, filling the box patterns, are as follows: cat, dog, mall, there and on. This activity was significantly more difficult for the subject, because it required the student to generate words—not just select from the word banks. The researcher is beginning to see the pattern that generation of sentences and words is difficult for the student. While the subject is creative, she tends to be more hesitant and ask for more assistance when there are not choices. Open-ended activities should be used to help stretch the student and take her out of her comfort zone. Schwendeman 27 Schwendeman 28 Reflection on “Intervention Lesson #5: Conclusion/Wrap Up” The student was ready for the Yopp-Singer outcome assessment today and was very pleased to see that she had improved since the beginning of the case study. She also was excited to see that I had brought back my tote bag of books and that we would have time for “free reading” once the book for the graphic organizer was read. The subject did a great job reading and filling the words as she read. After reading, the researcher assisted the subject in looking up definitions in a student dictionary. The subject was good with alphabetizing—but seemed to get a little lost after she found the first two letters in the word. For instance, she could find the words that started with “al” but struggled to find “almost.” After filling out the definitions, the subject was asked to reread the story and pause where the four challenging words were, and read the definition, to clarify the meaning of the words that were previously unknown. She read with much greater fluency the second time around. After the second reading, the student was asked to summarize the story. She was overwhelmed by all the writing, so she dictated to the researcher. (Her dictation is found on the green Post-It note on the worksheet.) Schwendeman 29 Schwendeman 30 PHASE IV: Impact on Student Learning Yopp-Singer Assessment 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Yopp-Singer Assessment Initial Screening Midpoint Progress Monitoring Outcome Based Assessment As evidenced by the chart above, the student was able to improve their score on the Yopp-Singer Assessment by two points throughout the course of the case study. As explained by the attached assessment information (see pages 31-36 of this document), scores 7-16 show that the student exhibits emergent phonemic awareness, and scores 17-22 show that the student is considered to possess phonemic awareness. The subject moved from emergent into the lower end of the phonemic aware category, which shows that the reader case study had a positive impact on the student’s literacy. The researcher feels that these positive results were directly linked to the practicing of segmenting phonemes each day before completing the vocabulary building activities. Also, having done the test twice previously during the case study, the reader knew what to expect for the outcome based assessment and felt better prepared. Schwendeman 31 The improved phonemic awareness was not the only positive impact that the reader case study seemed to have on the subject. The student also seemed to gain confidence in her reading skills—even though she was already fairly confident before the case study. The student’s hesitancy to participate in sentence building activities and ask for help diminished as the study went along. The subject also expressed excitement that she was chosen above her twenty-seven peers for the study—which evidences a boost in self-esteem and self-image. Another notable change in the subject was her work ethic and attention span. During the first intervention lesson, the student complained about having to write five sentences—however, by the end of the study, she was writing eight sentences (of greater difficulty) with little complaints or hesitancy. The instruction was designed in such a way that it built up her attention span because it started with easier, shorter lessons and grew to be more complex and require more attention and time to complete successfully. Overall, the student seemed to benefit from the interventions, not only gaining literacy skills, but also gaining self-confidence and work ethic. While there were issues with the case study, because of student absences, it seems that it was still an effective and worthwhile activity for the subject to participate. One may wonder, however, how the results would have looked if the case study had gone as planned and the student did not miss so much school. The researcher offers her opinion that the student would have had higher results had her initial plans been followed and the case study was done in a shorter time frame—rather than spread out over a longer period as it turned out to be. Schwendeman 32 Schwendeman 33 Schwendeman 34 Schwendeman 35 Schwendeman 36 Schwendeman 37 Schwendeman 38 Personal Growth as a Reading Teacher The subject was not the only individual who reaped the benefits of completing this reader case study. The researcher also benefitted because many skills were practiced and acquired through this experience that will help strengthen their reading instruction in future classrooms. One of the largest growths in the researcher was increased flexibility with lessons to adapt for the learner’s needs. When lessons did not go as planned, the researcher was able to come up with other creative and supplemental activities to help the student comprehend the concept—rather than being at a loss of what to do next. This shows great growth in the researcher herself from previous semesters. The researcher also had to be flexible with the lessons because the student missed several appointments that we had made; therefore, the researcher had to rearrange her personal and work schedule and was often given late notice as to when the interventions could be completed (based on the subject’s attendance). As mentioned in the background information for the reading, the researcher had feared this would happen. Lesson design and planning was also another area of growth for the researcher. Lesson plans were created to not only reflect what the individual student needed to work on to meet their case study focus goals of vocabulary development and phonemic awareness, but also to build upon one another. The researcher moved different activities around based on how the student preformed on the previous activities. For instance, the student struggled with generating original and creative sentences, so the researcher took an extra day to practice the skill and provided scaffolding when necessary by having multiple activities of varying difficulty for the student to complete. In implementing the lesson plans, the researcher was able to do so with less dependency on written lesson plans. The researcher was barely glancing at them by the end of Schwendeman 39 the interventions—which seems to indicate good lesson planning because the flow was so natural that the researcher did not need reminders or clues as to what was to be completed next. A goal that the researcher has developed in regards to future reading instruction is to be able to be as effective of a reading teacher in a larger group as she was in this one-on-one situation. One strategy that the researcher plans on using to accomplish this goal is to plan oneon-one conferences with students so that they are able to receive individualized attention (as the subject did during this case study) and the teacher will be able to develop her curriculum to better suit the individual needs of her students. It is this assessment-driven instruction that will benefit her future instruction the most. Schwendeman 40 References Gentry, J. Richard. "You Can Analyze Developmental Spelling…” Louisiana.gov. Web. 2 Oct. 2011.<http://sda.doe.louisiana.gov/ResourceFiles/Literacy%20Assessments/Monster%20 Test.pdf>. "Instructional Strategies Online - Cloze Procedure." Online Learning Centre. Web. 10 Oct. 2011. <http://olc.spsd.sk.ca/de/pd/instr/strats/cloze/index.html>. “Overview - Accelerated Reader." Renaissance Learning - Advanced Technology for DataDriven Schools. Web. 10 Dec. 2011. <http://www.renlearn.com/ar/overview/>. "Rigby Reading Evaluation and Diagnostic System [READS] Intervention." Rigby. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Web. 2 Oct. 2011. <http://rigby.hmhco.com/en/reads_int.htm>. "Running Records - Information on Running Records and How to Administer Them." Busy Teacher's Cafe - A K-6 Site for Busy Teachers like You! Web. 02 Oct. 2011. <http://www.busyteacherscafe.com/literacy/running_records.html>. Sight Words for Older Students. Scottsdale, AZ: Remedia Publications, 2000. Print.