Other Contemporary Views Deontological Theories

advertisement

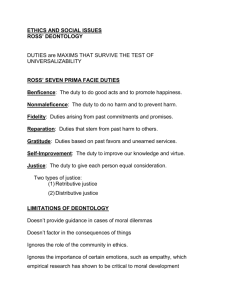

Other Contemporary Views Deontological Theories: Two Artic explorers have only enough food to keep one of them alive until he can reach the base. The first explorer offers to die if the second will promise to educate his (the first one’s) children. Should the utilitarian keep her promise? Given the utilitarian goal, should promises matter if they do not maximize overall happiness? Kant says that one has a sacred duty to another. We should never break our word no matter what. Is there a middle ground? Contract A contract is a promise, and there would seem to be a duty not to violate a contract if it has been voluntarily entered into by both parties. •It is not solely for utilitarian reasons that you have a contract. •It is not solely for egoistic reasons that you have a duty to honor a contract. •One of the main tasks of the law is to enforce contracts voluntarily entered. •The laws allow for exceptions. For instance, if there was an honest misunderstanding. Such as if two boats had the same name. Or, if it is impossible to complete the contract. Ought implies can. Or, if a contractor could not meet every single term, but could still keep the contract. Friendship Should you do the same for a stranger as you would do for a friend? A friend has listened about the details of your breakup at two in the morning, a friend has picked you up in the middle of the night when your car broke down, a friend has helped you study for your exams and has lent you money for books. Do you owe this friend more than you owe a stranger? How does owing somebody something fit into utilitarian theory? Ross’s Theory Sir David Ross (1877-1971) • Ross points out that we all have various duties. Utilitarians reduce all duties to one, the duty to maximize the good. •Ross claims that we have prima facie duties. Ross has a list of prima facie duties: •Duties of fidelity. The fact that a promise was made is a more powerful reason for keeping it than the fact that by keeping it you will maximize the overall good. •Ross believes the utilitarian makes the mistake of assuming that all duties are future-looking - duties to produce certain consequences in the future. However, some duties are pastlooking. Ross’s Theory Duties of Reparation: If I back my car into my neighbor’s fence, then I owe her a new fence. I can’t say, “Instead of fixing your fence I think I’ll give the money to the Salvation Army, because more good will be brought about that way.” Ross’s Theory Duties of Gratitude: Duty is personal: If we have to choose between saving someone that could do more overall good and saving our father, then wouldn’t we be justified in saving our father? Your father helped raise you, he put a roof over your head, lent you money, and so forth. Doesn’t he deserve your gratitude? Duties of Beneficence: We have a duty to promote the general good. This is our utilitarian duty, but it is only one among many. Duties of Non-Maleficence: We have a duty not to harm others. Ross considers this stronger than that of beneficence. Ross’s Theory Duties of Justice: Ross believes that justice does not have to do with the amount of good produced but with its distribution. If I have to decide if to give my $100 to a brother that is going to use it to purchase textbooks or $100 to a brother that wants to go on a shopping spree, then I should help the brother using the money to buy textbooks. It does not matter what the consequences are, only who deserves it more. Duties of self-improvement: We have an obligation to improve our own virtue, intelligence and happiness. Ross’s Theory Principles to resolve conflicting duties: 1. Always do that act in accord with the stronger prima facie duty. 2. Always do that act that has the greatest degree of prima facie rightness over prima facie wrongness. Problems with Ross’s Theory Where do we draw the line? We agree that we have duties of gratitude and duties of justice. What if our friend did pick us up at night when our car broke down, and lent us money when we were a little short. What if she did something wrong and wanted us to keep quiet? How do we decide if the duty of gratitude or the duty of justice is the stronger prima facie duty? Is Ross’s list accurate? What about duties to country and duties to future generations? Person-Relativity? To what extent am I responsible for my actions? See page 175. Rule Utilitarianism So far, we have been discussing act utilitarianism. However, there is a more contemporary view, called rule utilitarianism. According to rule utilitarianism, we should not do the act that will lead to maximum good, we should follow the rule whose general adoption would cause the most good. Act utilitarianism has a problem with those actions that have no utility unless all or most people do them. If a sign says, “Don’t walk on the grass,” and everyone has walked on and killed the grass, then the consequences are that you should walk on the grass. It is dead anyway, and walking through the area will help you get to class five minutes sooner. Criticisms of Rule Utilitarianism Cab rules be formulated for unique situations. Jean-Paul Sartre said that trying to give “the rule under which the act falls” does not help us to decide what to do in our unique situation. He gives the example of a young Frenchman that does not know whether he should joint the Resistance or stay home and help his invalid mother. How should he choose? Where do we go from there? No two people are ever in the exact same situation, so rules are useless. Conflicts of rules: What if two rules conflict? Criticisms of Rule Utilitarianism Complexity of Rules: • There are so many exceptions to rules that we can’t really know which one has an exception to it. • A rule is useless if it can’t be taught and if it is too complicated to learn. Just one rule? • At the opposite end of extreme complexity is extreme simplicity. Why not simplify the whole affair by saying, “Never tell a lie except when telling a lie will do the most good. • A rule with this much vagueness would be of virtually no use to anyone. Criticisms of Rule Utilitarianism Isn’t act utilitarianism sufficient? • Why do we need a rule? Can’t we figure the overall probable consequences of an act without a rule? Act utilitarians have called this “rule worship.” • Act with minimal consequences. See pages 184-185