What we wish we had known and didn*t know to ask:

advertisement

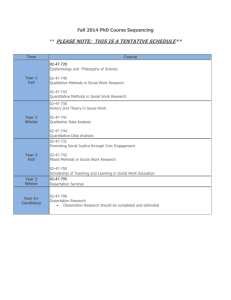

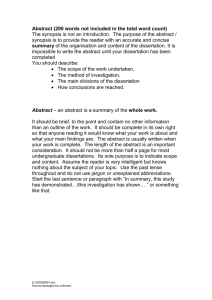

Taming the dissertation/thesis beast What we wish we had known and didn’t know to ask Dr. Dianne Cothran, dcothran@ufl.edu Dr. Mickey Schafer, msscha@ufl.edu Dial Center for Written and Oral Communication There are 4 phases to the project Phase One – search for a project, write the proposal Phase Two – conduct literature review, begin “experimental” phase Phase Three – Freak out and Revise study Phase Four – Write the dissertation Note: the formality of each depends on your field! Phase I: Write a Proposal/Prospectus Main objective – lay out the plan for the project Committee needs to know that: ◦ You know something about what you are doing ◦ You have a workable RQ ◦ You have a plan And yes, they do know all this may change. Proposals have 4 parts Part One – Exec Summary/Significance ◦ Short (1-2 paragraph) overview of topic, why it is significant, RQ, why RQ is significant Part Two – Lit Review ◦ 2-5 page exploration of expert literature in topic area Part Three – Methodology ◦ Lay out timeline, materials, cost, procedure,etc. Part Four – Tentative Bibliography ◦ Demonstrate you know your stuff Proposals vary in formality In some fields, the proposal is an extremely important document – it’s a step on the way to PhD candidacy In other fields, the proposal is a planning step – the committee wants to see it in order to help you Some fields may not require a proposal at all – you should still write one for the purpose of planning procrastination! Phase 2: Research is driven by questions. Method – is how you answer the RQ The best way to get research done is to formulate a question – just one question! ◦ You may need smaller questions along the way ◦ Your RQ answers grad students’ least favorite question: “What’s your thesis about?” ◦ RQ Wh-question, may be yes/no, but that takes some serious you-know-what-body-part Methodology is Discipline Specific. ◦ Humanities ◦ – lots of thinking, reading, more thinking, and some more reading New Methods for Humanities Research -http://www3.isrl.illinois.edu/~unsworth/lyman.htm Digital Research Tools Kit -http://digitalresearchtools.pbworks.com Method: SSB ◦ Social and Behavioral Sciences – IRB? Quantitative (stats driven) Qualitative (words/analysis driven) Mixed (umm, well, both!) Web Center for Social Research Methods -http://www.socialresearchmethods.net/ Digital Research Tools Kit -http://digitalresearchtools.pbworks.com/ Methods: bio/phys ◦ Biological and Physical Sciences – P.I.’s project Quantitative Discipline-specific research protocols Bioexplorer.net -http://www.bioexplorer.net/Methods_and_Protocol s/Resources/ Phase 2 – conduct the literature review The proposal included a tentative bibliography and lit review to support your Big Idea. In most dissertations, the literature review is the first big thing in the dissertation ◦ Is the “proving ground” where you show that you’ve done the necessary work ◦ Still functions to lead to gap motivating RQ Control the literature (or it will control you) Use the FFSP method (find, filter, select, prioritize) ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Find using databases (see subject guides) Filter using abstracts Select after a quick skim Prioritize according to impact on project Any of these steps can be done on their own! There does come a time when you will have to stop reading! The lit review has two jobs. The lit review provides a state-of-the-art overview of your area of research ◦ Think in terms of concept maps ◦ Use subheadings! They are your friend. ◦ This is NOT a function of the lit review in publication (so check with advisor what version they want) Lit review leads to gap motivating your research ◦ This function is true for publications, too Phase 3: Freak out and Revise If you don’t do this once, your committee gets worried that they have nothing to do! Seriously, it’s pretty normal to get part way through and hit a big, nasty existential crisis on the meaning/value/utility/ worthiness of your project. This seems to be a natural product of Deep Thought. Phase 4: Write the Paper Look at models in your department – get inspiration and direction from what others have done Doing something that isn’t well represented by former graduate students? Look at published stuff. Check with mentor/chair for what they want you to produce – dissertation, publication, or both. More on writing: Start writing with what you know/are most comfortable with You will need to pre-write! Make outlines and concept maps, paint a blackboard on your bedroom wall, use giant sticky pads, draw cartoon bubbles Use your proposal to guide the first couple of chapters Use Visuals Effectively Use the terms “figure” and “table” Number figures/tables consecutively throughout the entire dissertation or thesis Give each visual a descriptive title In the text of your dissertation/thesis, discuss each table and figure One last slide: Make the Results section mirror Methods For the Conclusion, don’t re-hash the Results; interpret them! Write the abstract last Above all, BE CLEAR ◦ This may seem obvious, but your committee doesn’t live inside your head with you and you will really have to explain everything Decide what needs to be published AND DID WE SAY. . . . BACK UP YOUR WORK!! BACK UP YOUR WORK!! BACK UP YOUR WORK!! BACK UP YOUR WORK!! BACK UP YOUR WORK!! Tips for Taming the Beast Be flexible Communicate with major professor/ committee Have a plan for work Know the rules Expect things to go wrong Back up your work A collection of links for you at: http://web.clas.ufl.edu/users/msscha/diss_links.html In summary. . . Have a plan/schedule for writing Expect delays/obstacles/disasters Field test your work as you go along with people other than your committee Remember, others have made it, and SO WILL YOU! Defending your Dissertation Teaching the Beast to Behave What is a Defense? Purpose of the PhD process is to birth a colleague – ultimately, committee needs proof that you can “think” like a member of the discipline – this means demonstrating that you know: What makes your discipline unique; your discipline’s key ideas / concepts / contributions the kinds of questions your discipline asks the methodology the discipline uses to answer questions How to be a member of the club. can design/work within discipline’s methodology/frame to critique within field that you can use all of the above to innovate/practice in your field the defense especially tests the last 2 points: that you understand your discipline well enough to critique in the framework of your discipline and hypothesize at the boundaries of what you know in a way that is recognizably discipline-specific. Defending is not supposed to be easy. The high-stakes portion of your defense is supposed to push you to the point you “break” – i.e., that you cannot answer a question with content-knowledge, but must “guess” (remember, in academics we call intelligent guessing “hypothesizing”). You cannot possibly know everything. Get past the desire to be master of all content because… Content exists as a product of method/ approach/process. It is more important that you can demonstrate HOW your discipline works. What are you defending? “dissertation defense” may be a misnomer since there can be more than one thing that needs defending… ◦ Proposal ◦ Qualifying Exams ◦ Dissertation All But Dissertation AND different defenses can have different outcomes attached: ◦ High Stakes, Lower Stakes, No defense Step One: Find out what you need to defend. What do you have to prepare? What do you have to produce? What do you have to defend? Note: dissertation defenses are usually public (they have to be advertised and are open to everyone) – however, proposal and quals defenses are often private. Step Two: Find out what options you have for defending. Is there a presentation preceding questions? (If this is an option, take it!) Are visuals allowed? What formats are permitted (.ppt, poster, handouts)? How long does the process usually take? (the longer the process, the more preparation is required) Step Three: Prepare the Defense Create a “map” of your proposal / quals / dissertation – whatever it is that you need to defend. For each section, list the main ideas. For each main idea, map out related literature (include author/s & dates, and page # in your work), related evidence (data: your stuff, too), and potential objections. “Potential Objections” are the KEY to controlling your defense. Think objectively about your work, your claims, the way you constructed arguments (if you cannot do this or there isn’t enough time, find someone in your department who will). Generate reasonable objections. Then, prepare answers to those objections. Prepare a Presentation (if an option) Think of this more like a conference presentation to colleagues rather than a defense. Incorporate the most important objections into your presentation, and (of course), provide your response. Keep to time limits – if only given 10 minutes, then hit the main points: topic/significance,“research question”, “method”, “results”, and contribution to field. Work in objections briefly, if time (if no time, then reserve that preparation for the Q/A period). If 20 minutes, that’s enough time to get across main points and address major objections. Step Four: Go Forth and Defend! Get out the “map” you made and have it handy – be familiar with it so you can find things easily – make sure it’s neat, legible, and usable. Even for a high stakes defense, keep it cordial. This is an academic conversation…you should remain calm. Let your committee members be the ones to argue (and they just might!). It helps if you’ve had sufficient sleep and decent food in the previous 24 hours! Typical academic questions to expect: http://www.wmich.edu/coe/fcs/cte/doctoral/oraldefense.htm Prepare for “other” questions Be prepared to answer “soft” questions – how you decided on this research question; what do you think is most important “take away” point; what do you think is the most damning problem; can you apply it/extend it; what should come next; if you could do it over, what would be different; what do you want to do next? (http://www.dissertationdoctor.com/advice/questions.html) Be mentally prepared for questions that just seem weird – maybe they are “left field” questions, maybe you don’t understand the significance of the question (even though you know the answer,), maybe it’s something so specific and nitpicky that you didn’t even identify it as a possible problem. Feel free to ask for clarification, e.g. “That’s an interesting question, but to make sure, [restate Q]– is that what you meant?” Prepare for disagreement, digression Be mentally prepared to disagree with a committee member, to actually “defend” your work. Remain civil and confident. The“A but B” strategy is an effective, academic-y way of dealing with conflict. “A” are the points of agreement, “but” is whichever logical connector works best (still, yet, however, nonetheless, despite, etc.), and “B” represents the counterpoints, e.g. “yes, while it’s true that X,Y, and Z are traditionally agreed upon, inconsistencies in the way that Y is defined weakens the likelihood that it can account for Z. Instead, if Y is broken down into U and V, then Z is a far likelier outcome”. Committee members may digress into their own conversation – enjoy the break! Hungry people make grouchy audiences! A Final suggestion…feed the beasts! And by “beasts” we mean your committee members, who are not at all beastly, yet may nonetheless appreciate food & drink. ◦ Fruit, cheese, bread/cracker platters can be eaten any time during the day. ◦ Bring coffee/juice/water. No alcohol! ◦ May bring home-cooked food but be smart about choice. ◦ Remember plates, forks/spoons, cups, napkins. ◦ Keep is simple and modest. ◦ Before including food, check with department.