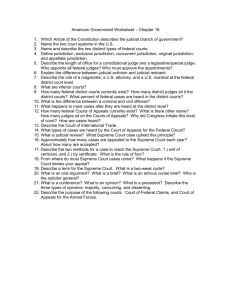

Federal court

advertisement