14.1 Romangovernment

advertisement

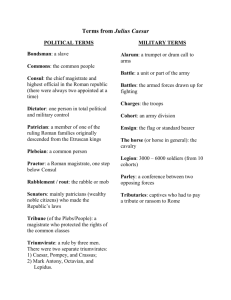

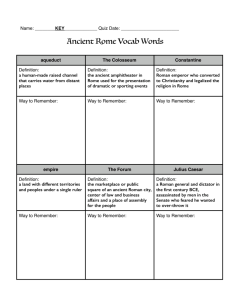

The Roman Republic How the government was supposed to work. And how it really did. Rome Before Emperors • Some Latin 1-2 courses spend little or no time talking about the government of Rome before Julius Caesar, so if this is all new, don’t feel bad. • Some basic information about the structure of Republican government is necessary to make any sense of this reading. Key Terms • Consul=elected head of state. There were always two at once. The term was only one year. • Senator=anyone who had previously attained elected office at the rank of quaestor or higher (i.e., you were never directly elected to the Senate) More Key Terms • SPQR: Acronym for senatus populusque Romanus. It is worth remembering that the Senate was not actually the only governing body of the Roman Republic. There was also an assembly of the people. The speech we are reading is addressed to the Senate, but Cicero also addressed the people on this matter. Still more--in Latin! • Cursus honorum: literally, “the course of elected positions”. A progression of government jobs of increasing responsibility, leading up to the highest rank of consul. • Consularis: a member of the Senate who had previously been consul. A consularis got to speak before other members did. A consularis could run for consul again, but only after ten years had passed since his term. (As the Republic broke down this rule was frequently ignored.) • Novus homo: close to American English “self-made man”, this meant a person who became consul when none of his ancestors had done so. This was rare (to a large extent by design). Late Republican Political “Parties” • Romans did not have a formal party system like most functioning modern republics do, but it did have two major factions that served a similar purpose. • Optimates were the “conservative” party. However, that doesn’t mean that they necessarily shared values with modern conservatives. “Conservative” just means that you put political value on preserving elements of past government and/or culture: and for Romans, that meant the dominance of wealthy landowning families who had been in government for generations. • Populares, on the other hand, tended to advocate for causes that would appeal to a larger proportion of the Roman population (remember, the Assembly of the People was also a force to be reckoned with). Optimates • From our perspective, it can be very hard to comprehend the optimate political position. How could you justify giving most power to people who already had wealth and a long history of having power and wealth? It goes against our grain. • However, a Roman optimate might well wonder why you didn’t see his point. Surely those who have the most in society will take better care of it? They have the most to lose if it falls apart. • (It’s also a useful historical corrective to remember that most of the original American states, who were consciously using the Roman Republic as a model for government, had property qualifications for the vote. Many people forget that. These attitudes aren’t as far removed from us as we might think.) Populares • We have few surviving sources written from a populist position, so it is hard to say how many populares were ideologically committed to helping the poor, and how many saw that they were a big voting bloc. • Issues likely to appeal to the poor could include distribution of land to the urban poor, food aid, debt relief, etc. So how did you get elected? • All Roman voting was done in person. There were no secret ballots. The city population was split into groups, who all voted together with a “yea/nay”. • All citizens got only one vote. However, the system was intentionally biased so that wealthy people who lived in Rome itself counted more: • The wealthiest groups voted first, and the election was called once the math became clear, not necessarily when everyone was done. Many poorer people probably thought it was a better idea to stay home and work than waste a day waiting in line for a turn that might never come. • Though citizens not resident in Rome had the vote, there were no absentee ballots, which cut down on participation by allies. Um, not-so-good reasons to vote • We know a great deal about Roman campaigning from sources ranging from graffiti to a manual on how to run for office which may actually have been written by Cicero’s brother Quintus. We also have court cases prosecuting candidates for their behavior during elections. And it was clearly a thoroughly dirty system in Cicero’s day. • Bribery was illegal, but also basically compulsory. Take a look at the picture of the food/booze bowls with slogans at the start of the unit. Wealthier voters could get cash bribes--and would then expect all their clients to vote the way they did. • Rumors, whispering campaigns and poorly fact-checked smear stories were par for the course. Violence and intimidation were becoming an increasing problem in Cicero’s day. So Now You’re In the Senate! • The Senate conducted its business, somewhat like a modern house of representative government, with a presiding official (the consul) and senators who attempted to sway votes with speeches. • To really imagine a day in the Roman Senate, however, you should get C-SPAN straight out of your head. US Congress operates by very strict rules of order that prevent most kinds of rudeness and restrict unfounded statements. It keeps our government civil but is also the reason hardly anyone watches C-SPAN. • A contentious day in the Roman Senate would have been full of insults, yelling, interruptions, half-baked insinuations, personal dirt that we would usually consider irrelevant, etc. . . .