The Use of Virtual Reality for Persons with Balance Disorders

advertisement

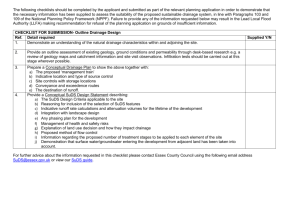

The Use of Virtual Reality for Persons with Balance Disorders Susan L. Whitney, PT, PhD, NCS, ATC University of Pittsburgh Supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Introduction • The use of virtual reality with persons with vestibular disorders is a relatively new concept • Persons with vestibular disorders often complain of having difficulty maintaining their balance when exposed to complex visual scenes Introduction • Persons with vestibular disorders have abnormally large, visually induced postural responses • It is impossible to replicate visually complex visual environments in a rehabilitation setting and control the input The BNAVE (Balance Cave Automatic Virtual Environment) • It was custom built with a viewing angle of 200 degrees horizontal and 90 degrees vertical (Figure 3) • Each display (3) is produced by a VREX 2210 LCD-based stereoscopic digital projector controlled by an Intel PIII computer The BNAVE (Balance Cave Automatic Virtual Environment) • Lab View software is used to interface the signals between the software and hardware • Data from the force platform and head sensor were sampled at 120 Hz Design of the BNAVE Right side projector. Left side projector. Front projector. Sinusoid, 0.1 Hz Sinusoid 0.1 Hz, 4 sq./m, 4 m/s 5 0.35 4 3 RMS A-P COP (cm) COP, Hea d X-lation (c m) 0.3 2 1 0 -1 -2 0.2 2 m/s 4 m/s 0.15 0.1 -3 Head -4 COP -5 0.25 0 10 20 30 Time(sec) 40 50 0.05 60 0 2 SQ/m 4 SQ/m Block Size Postural Sway in a Virtual Environment in Patients With Unilateral Peripheral Vestibular Lesions Susan L. Whitney, PhD, PT, NCS, ATC Patrick J. Sparto, PhD, PT Kathryn E. Brown, MS, PT, NCS Mark S. Redfern, PhD Joseph M. Furman, MD, PhD Departments of Physical Therapy, Otolaryngology and Bioengineering University of Pittsburgh Introduction • Vestibular compensation adjusts for abnormalities in the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) and postural stability seen acutely following unilateral peripheral vestibular lesions (UPVL). • Long term visual dependence of individuals with UPVL has not been fully examined. • Also, the ability to receive cues from the periphery in these individuals has not been studied. Purpose • The goal of this study was to assess the visual motion sensitivity of patients with chronic UPVL’s. • Another objective was to determine the amount of discomfort each individual perceived after each trial. Methods • 24 gender and age matched patients and controls were recruited to participate. • Gender: males – 10; females – 14. • Age: Range: 31 – 66; Mean: 49.5 ± 10. • Patients time (in months) since unilateral peripheral vestibular loss: – Range: 10 – 72 mos. – Mean: 38.9 ± 21.5 mos. Methods • Each subject participated in one 8-trial virtual reality session. • There was an initial and final “quiet” trial with nothing displayed on the screen. Methods • Each subject was tested under 3 different field of view conditions (FOV). – Full vision. – Peripheral vision only (30º). – Central vision only (30º). Methods • Each subject was also tested under 2 different frequencies of visual scene movement in a sinusoidal fashion. – 0.1 Hz movement. – 0.25 Hz movement. Experimental Design • Independent variables: – FOV – Frequency of tunnel movement – SUDS rating • Dependent variable – Amount of sway Methods • Subjects stood on force platform with their feet comfortably apart, wearing a harness support to prevent a potential fall, measuring center of pressure (COP). • The subjects’ head movement was measured using an electromagnetic position and orientation sensor affixed to an adjustable plastic headband. Methods • Eye movement was monitored to insure that eyes remained straight ahead. • All data was collected with the room darkened. Methods • Preliminary objective and subjective data collected include: ABC, DHI, BP, HR, Situational Characteristics Questionnaire, and the Simulator Sickness Questionnaire. • BP, HR, and level of discomfort (Subjective Units of Discomfort – SUDs) measured prior to start of trial. Methods – SUDs were measured after each trial. – BP and HR were measured in the middle of the session and again at the end. • When measuring level of discomfort or anxiety, the subject is asked to rate their level on a scale of 0 to 100 with 100 being the greatest. Methods • A visual stimulus of an infinitely long tunnel with checkered walls was displayed in the BNAVE, a virtual environment display facility. • Subjects stood barefoot for 80 seconds while viewing sinusoidal movements of the virtual tunnel. • Sixty seconds of movement were preceded and followed by 10 seconds of quiet standing. Data Analysis • Analysis of variance with repeated measures was used to test for the effects of subject group, movement frequency and FOV condition. • Non-parametric statistics were used to look at the main effects of the independent variables on the SUDs. • Non-parametric correlation coefficient was used to examine the association between sway and the SUDs. Pt 2, 0.10 Hz, Peripheral Vision 6 Head Position (cm) Tunnel Position (m) 4 2 0 -2 -4 Head Position Tunnel Position -6 0 10 20 30 40 Time (s) 50 60 70 80 Pt 2, 0.10 Hz, Central Vision 6 Head Position (cm) Tunnel Position (m) 4 2 0 -2 -4 Head Position Tunnel Position -6 0 10 20 30 40 Time (s) 50 60 70 80 Results – FOV & Frequency • There was no difference in amount of sway elicited in patients vs. control group, regardless of FOV condition or frequency of visual scene movement. • The amount of sway was significantly affected by FOV (p=.000). • The amount of sway was significantly affected by frequency of visual scene movement (p=.003). Results – FOV Conditions Effect of FOV on Sway 0.7 RMS in cm 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 Full Peripheral Central Results – Frequency vs. Sway Effect of Frequency of Movement on Sway 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 0.1 Hz 0.25 Hz Results • The SUDs level was significantly affected by FOV (p=.000). • The correlation between the SUDs and sway was significant (rs= .32, p=.000; n=137). – Many of the SUDs scores were clustered between 0 and 10. Effect of FOV on Perceived Level of Discomfort/Anxiety 20 15 10 5 0 Full Peripheral Central SWAY Sway vs. SUDs levels 4 3 2 1 1='pt',2=cn' 2.00 0 1.00 -20 SUDS 0 20 SUDs > 10 40 60 80 100 Conclusion • FOV significantly influences visual motioninduced sway in normal and in patients with chronic UPVL. • Frequency of visual scene movement also significantly influences sway in normal and in patients with chronic UPVL. • Level of discomfort (SUDs) is significantly affected by FOV in normal and patients with chronic UPVL.