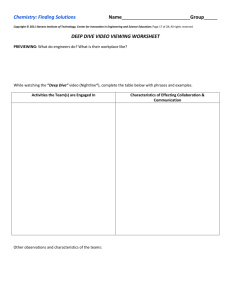

Norma Rae 1980 Washington Post Article

advertisement

Copyright 1980 The Washington Post The Washington Post June 11, 1980, Wednesday, Final Edition HEADLINE: Through the Mill With Crystal Lee and 'Norma Rae'; Through the Mill: The Labors of Crystal Lee Sutton BYLINE: By Megan Rosenfeld BODY: There's a scene in the movie "Norma Rae" were Sally Field, playing the hard-working, hardheaded textile worker who defies the company to help start a union, goes skinnydipping with the young Jewish labor organizer from New York on a hot day. Crystal Lee Sutton thought that scene was funny. "Isn't it a shame," she told the real-life labor organizer, "that we didn't have that much fun?" Some of Cyrstal Lee Sutton's life and times were dramatized in "Norma Rae," but after the victorious election that ends the movie, the real-life scene was that she had to find a job. The first one she got after she was fired from J.P. Stevens in Roanoke Rapids, N.C., was at a fast-food fried chicken stand in another town. It was the worst job she ever had. This was after she'd been fired from J.P. Stevens for "insubordination," and after her story had been written up and was about to be dramatized on celluloid as "Normal Rae." (Note: J.P. Stevens is the real name of the company that owned the factory depicted in the film.) "They bring the chickens in frozen, you got to process'em. You got to go in a freezer and fix up this mixture with so much cold water, you got to make sure the water's at the right temperature, you got to pull the fat out of those frozen chickens, you got to put 'em in this great big tub, 100 chickens at at time, and you are expected to pull that fat out in a certain amount of time. "Then you got to put 'em in this processing mixture and it stays overnight. Then you got to go back into the freezer, in that cold water and take those cold chickens out . . . and then you got to cut those chickens right in that freezer. You put on a glove that's got chains on it, because you're workin' around that power saw . . . You cut it through the breastbone, then the wing part, you know, then you got a certain way you cut the thigh and leg. We had to cook the chickens, you got to batter 'em, you got to fry 'em, you got to go in the morning and get the stoves hooked up. You got to work the cash register. You got to box the chickens . . . Then we had to mop the floor at night, and make sure those stoves were absolutely clean . . . "I'd rather shovel s---, to put it bluntly. I think that would be easier." The best job she ever had, in fact was at J.P. Stevens, where she folded towels into boxed gifts sets for $2.65 an hour. Her job now is, essentially, giving interviews. She is paid as an organizer for the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union (ACTWU), the union that won the right to represent the workers at the Roanoke Rapids plant on Aug. 28, 1974. After she was fired by J.P. Stevens -- she says it was for copying down from the company bulletin board a letter she describes as anti-union and racist; the company says it was for "insubordination" -- she was reinstated by a court order in 1977 and awarded $13,436 in back wages. She went back to work for two days just to "prove a point." For the last four years the ACTWU has organized a boycott against J.P. Stevens products, an anniversity they are celebrating this week by bringing Crystal Lee Sutton to Washington and showing "Norma Rae" on Capitol Hill. A spokesman for J.P. Stevens said the company's sales and profits last year were "record highs," a claim the boycott organizers question. The battle of the union (orginally it was the Textile Workers Union of America, which merged with the 500,000-member ACTWU in 1976) and the company has become one of the epic sagas of union-versus-management history -- one fought more with the modern tools of public relations than old-fashioned fists. It's been going on since 1963, through the courts and the National Labor Relations Board and the living rooms and meeting halls of the South, and there is no end in sight. "Norma Rae" is probably one of the most powerful tools the labor movement will ever have. Its moving saga of simple good and bad, of plain people winning against the badguy establishment, has inspired thousands and certainly clinched a career uplift for actress Sally Field, who will always be remembered holding up that UNION sign. But, of course, real life isn't that simple. Cyrstal Lee Sutton doesn't have a 22-inch waist, and the labor movement is not a simple morality play between the good (workers) and the bad (management). Cyrstal Lee Sutton is just a woman -- feistier and more plainspoken than most, but possessed of no mythical powers. Her gifts are her convictions and her willingness to be heard -- a willingness that in a small North Carolina town was courageous, but on the larger stage where so many causes are fighting for attention, she may seem to be just another voice in a chorus. Cyrstal Lee Sutton has worked hard most of her life. She admires work; when she describes someone she likes; she often says "She's a hard worker," or "They're good workers." She is what people are talking about when they say "working class." She started working at 16. At 17, she was a "battery filler" on the 4 p.m.-to-midnight shift at a textile plant. At 19, she had her first child. At 20, she was widowed. At 21, she had a second child; her third was born in 1965. She grew up in Roanoke Rapids, a town divided clearly into workers and managers, as she recalls it. "All my life, textile workers were looked down on. The doctors and lawyers and managers didn't want their children to associate with us. They always had new clothes, they were the smartest. They were the cheerleaders, and the majorettes -anything outstanding, it came from your higher class of people." Cyrstal Lee Sutton is a simple, straightforward woman. She has long hair that she hasn't cut for 15 years. At 39, she no longer wears makeup, and her clothes are often something she has made herself. Her celebrity, which is increasing now that she is on the union payroll and being built up as a labor heroine, has helped insure that her children do not suffer from the classism she was so conscious of. "My children don't run in the same class I did," she said. "Because thank God I've been able to provide them with decent changes of clothes and all. They run with any class of people. They have been brought up with the idea that nobody is better than you are, but you are not better than anybody else. They don't look down on anybody just because they don't live in a fancy house of wear fancy clothes." Cyrstal Lee lived in a "fancy" house once, when she was married to her second husband, "Cookie" Jordan. "I tell you what," she said, "if I had to live in a shack I could keep it clean. A fancy house does not make a home . . . I had a fireplace, a back yard, azaleas, a dogwood tree. But I wasn't happy." It was through Cookie Jordan that she got involved with the union in the first place. "My family had worked in textiles all my life. And my husband worked at a unionized plant [a paper mill] and he had so much better benefits. He had four weeks paid vacation and my parents had one week paid vacation after 30 years. So I thought if the union had done that much for him, I wanted to have the same thing. So she went to a meeting of the fledgling union, which was being organized by 55-yearold Eli Zivkovich, a former coal miner from West Virginia who was transformed in the movie "Norma Rae" into a zippy young intellectual type from New York. In the climactic scene of the movie, after Norma Rae has been fired, she stalks back into the plant, writes the work UNION on a piece of paper and stands on a table to show it to all her co-workers above the din of the machines and is then carried out by police. That really happened. What didn't really happen is that everyone lived happily ever after once the union won the election. For one thing, there is still no contract signed between J.P. Stevens and the ACTWU in Roanoke Rapids. For another thing, Cookie and Crystal Lee split up. "Before, I was working second shift, so like in the mornings I could do the laundry, I could clean the house and I could cook dinner before I went to work. But when I got involved with the union, I was working at trying to help Eli organize people. And then there was just no way that I could do what I had done before because then I had two jobs. And a lot of times I'd come in with hamburgers instead of having a hot meal on the table. And he thought I had to do the laundry every day. And that started causing trouble. And he didn't want his wife to get involved, because like he told me, "You're going to get fired." "He didn't want me to go to the first union meeting because it was held in an all-black church . . . Every day I'd come home he'd say, 'Well, you made it through one more day, did you?' So then when I did get fired I was mad as hell. I was mad at the company but then I was made at him because he had said I would get fired." After their separation in 1976, she found it hard to get a job and believes it was because of her union activities. She moved more than 100 miles away, where her job at the friedchicken stand was the first of many she subsequently had. Now she is married to Lewis Sutton, who works at a unionized textile plant. "His dues help to pay my salary," she said with a smile. Her oldest son works in construction and has a 3-month-old baby (his wife just graduated from high school and will soon start work at a "towel place.") Her son Jay sought her help in organizing workers at the hotel where he worked last fall (the election produced a tie vote). Elizabeth, her daughter, is finishing high school -- much to Crystal's Lee's relief. "She hates school as much as I did." The movie, which won an Academy Award for Sally Field but not a cent for Crystal Lee Sutton, was based on a book detailing the lives of Southern textile workers. Sutton thinks it is "funny. It made me cry in parts and it made me laugh . . . I just thought if they're going to spend millions of dollars making a movie, I wanted it be a good educational union movie, not a soap-opera love story like you can see every day on TV." A spokesman for J.P. Stevens in New York said that the boycott of its sheets and towels has not been effective, that sales and profits last year were higher than ever. He also said the union was spending $5 million a year "to send people like Cyrstal Lee Sutton around taking potshots at us," and that if the boycott were successful it would ultimately hurt the 34,000 people who work at J.P. Stevens. The contract has not been signed in Roanoke Rapids, he said, because the union "keeps stalling on specific contract provisions." The company "believes the employees would be better off without a union, but it has never tried to avoid an election," he said. "Four years ago we started a campaign to get the union to have elections; it's the only proper way to decide this question," he said. "But this union has a credibility problem in that they have lost 80 percent of the elections they've held at other companies' plants." (Actually, union officials say they win about 46 percent of their elections, which is comparable to other unions.) Furthermore, he said, "They point to this 'Norma Rae' movie as an example of conditions in a J.P. Stevens plant. That movie was shot in a unionized plant in Alabama. If they are so concerned about conditions, why don't they start there?" The union and its supporters disagree. Pam Woywod, who traveled with Crystal Lee Sutton to Washington, said that J.P. Stevens had been cited 22 times by the National Labor Relations Board out of the 23 times the union has brought complaints against the company since 1963. While total company sales and profits may be up, she said the sales of sheets and towels, the only items the union can legally boycott, are down. The union spent a total of $5 million between 1977 and 1979 on organizing and legal fees, as well as the boycott, she said. As for the plant in Opelika, Ala., where the movie was made, Woywod said the cotton dust was allowed to accumulate for two weeks before the filming in order to approximate the conditions at the plant where Cyrstal Lee had worked. Even then, she said, blowers were used to make it fly around. The tenor of the boycott campaign is emotional and directed as much at public consciousness as at union organizing. "You don't have a lunch break," read one comment in a film on J.P. Stevens by the National Citizens Committee for Justice for J.P. Stevens Workers. "You eat while you're working. You lay your sandwich down in lint. And lint gets in your drink . . . After you give all your life to 'em, then . . . when you start getting old . . . they start tryin' to get rid of you . . ." Pitches like this the company finds offensive. They say their workers are paid, on the average, more than other textile workers in the South (another claim the union disputes). These disputes are merely an indication of the extent and complexity of the enduring battle between ACTWU and J.P. Stevens. For Cyrstal Lee Sutton, who is "trying to be less emotional as I get older," the union changed her life. She is a believer. Her life, and those of her friends, is far away from the exclusive halls of Capitol Hill, the company board rooms or even the inner circles of union power. She is the kind of person who takes it on the chin when a union official is convicted of corruption, or when the sophisticated outwit the simple. "I can only talk about what I know," she said. ". . . The textile worker is a important worker.We didn't have any respect. We didn't have decent working conditions. I just decided if it was okay for other people to have unions, I didn't see why we couldn't."