WorkinProgress–NeoliberalRacialOrder

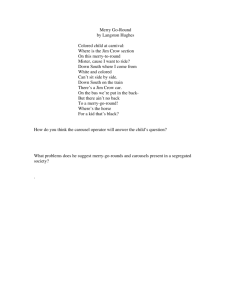

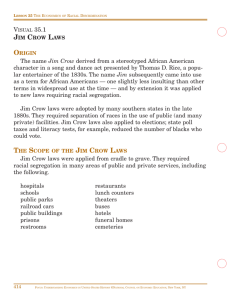

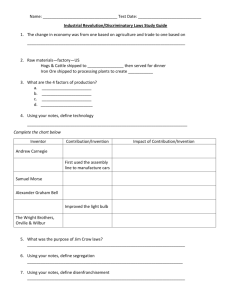

advertisement