Sherman Alexie Poem Analysis Read BOTH poems by Sherman

advertisement

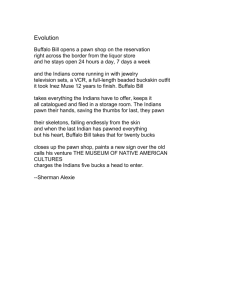

Sherman Alexie Poem Analysis Read BOTH poems by Sherman Alexie and complete the accompanying response sheets. (Be sure you read the background info on Buffalo Bill before tackling “Evolution.”) After you have completed your own reflections and analyses, read the provided criticisms from Modern American Poetry. Select ONE poem for this assignment. Choose the poem that you feel most comfortable with. Task: Write a multi-paragraph essay in which you 1. analyze the poem in regards to theme, tone, and style (sound techniques, figurative language, diction, syntax, figurative language, etc.) and 2. respond to the literary criticism provided. Some things to consider: - Use direct quotes from the poem and criticism to illustrate and support your claims (with proper in-text citations). If you claim he uses figurative language, offer an example of figurative language. Don’t just address the WHAT; address the WHY. Why does he use sensory details? What effect do they have on the reader? Consider using IRE structure to set up examples. Be sure you introduce quotes and transition into them smoothly. Don’t let them float! Say something interesting. Really dissect them poem. Be sure to include a Works Cited page. About Buffalo Bill--Background to "Evolution" William F. Cody "Buffalo Bill" (1846-1917) In a life that was part legend and part fabrication, William F. Cody came to embody the spirit of the West for millions, transmuting his own experience into a national myth of frontier life that still endures today. Born in Scott County, Iowa, in 1846, Cody grew up on the prairie. When his father died in 1857, his mother moved to Kansas, where Cody worked for a wagon-freight company as a mounted messenger and wrangler. In 1859, he tried his luck as a prospector in the Pikes Peak gold rush, and the next year, joined the Pony Express, which had advertised for "skinny, expert riders willing to risk death daily." Already a seasoned plainsman at age 14, Cody fit the bill. During the Civil War, Cody served first as a Union scout in campaigns against the Kiowa and Comanche, then in 1863 he enlisted with the Seventh Kansas Cavalry, which saw action in Missouri and Tennessee. After the war, he married Louisa Frederici in St. Louis and continued to work for the Army as a scout and dispatch carrier, operating out of Fort Ellsworth, Kansas. Finally, in 1867, Cody took up the trade that gave him his nickname, hunting buffalo to feed the construction crews of the Kansas Pacific Railroad. By his own count, he killed 4,280 head of buffalo in seventeen months. He is supposed to have won the name "Buffalo Bill" in an eighthour shooting match with a hunter named William Comstock, presumably to determine which of the two Buffalo Bills deserved the title. Beginning in 1868, Cody returned to his work for the Army. He was chief of scouts for the Fifth Cavalry and took part in 16 battles, including the Cheyenne defeat at Summit Springs, Colorado, in 1869. For his service over these years, he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor in 1872, although this award was revoked in 1916 on the grounds that Cody was not a regular member of the armed forces at the time. (The award was restored posthumously in 1989). All the while Cody was earning a reputation for skill and bravery in real life, he was also becoming a national folk hero, thanks to the exploits of his alter ego, "Buffalo Bill," in the dime novels of Ned Buntline (pen name of the writer E. Z. C. Judson). Beginning in 1869, Buntline created a Buffalo Bill who ranked with Davy Crockett, Daniel Boone and Kit Carson in the popular imagination, and who was, like them, a mixture of incredible fact and romantic fiction. In 1872 Buntline persuaded Cody to assume this role on stage by starring in his play, The Scouts of the Plains, and though Cody was never a polished actor, he proved a natural showman, winning enthusiastic applause for his good-humored self-portrayal. Despite a falling out with Buntline, Cody remained an actor for eleven seasons, and became an author as well, producing the first edition of his autobiography in 1879 and publishing a number of his own Buffalo Bill dime novels. Eventually, there would be some 1,700 of these frontier tales, the majority written by Prentiss Ingraham. But not even show business success could keep Cody from returning to the West. Between theater seasons, he regularly escorted rich Easterners and European nobility on Western hunting expeditions, and in 1876 he was called back to service as an army scout in the campaign that followed Custer’s defeat at the Little Bighorn. On this occasion, Cody added a new chapter to his legend in a "duel" with the Cheyenne chief Yellow Hair, whom he supposedly first shot with a rifle, then stabbed in the heart and finally scalped "in about five seconds," according to his own account. Others described the encounter as hand-to-hand combat, and misreported the chief’s name as Yellow Hand. Still others said that Cody merely lifted the chief’s scalp after he had died in battle. Whatever actually occurred, Cody characteristically had the event embroidered into a melodrama--Buffalo Bill's First Scalp for Custer--for the fall theater season. Cody’s own theatrical genius revealed itself in 1883, when he organized Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, an outdoor extravaganza that dramatized some of the most picturesque elements of frontier life: a buffalo hunt with real buffalos, an Indian attack on the Deadwood stage with real Indians, a Pony Express ride, and at the climax, a tableau presentation of Custer’s Last Stand in which some Lakota who had actually fought in the battle played a part. Half circus and half history lesson, mixing sentimentality with sensationalism, the show proved an enormous success, touring the country for three decades and playing to enthusiastic crowds across Europe. In later years Buffalo Bill’s Wild West would star the sharpshooter Annie Oakley, the first "King of the Cowboys," Buck Taylor, and for one season, "the slayer of General Custer," Chief Sitting Bull. Cody even added an international flavor by assembling a "Congress of Rough Riders of the World" that included cossacks, lancers and other Old World cavalrymen along with the vaqueros, cowboys and Indians of the American West. Though he was by this time almost wholly absorbed in his celebrity existence as Buffalo Bill, Cody still had a real-life reputation in the West, and in 1890 he was called back by the army once more during the Indian uprisings associated with the Ghost Dance. He came with some Indians from his troupe who proved effective peacemakers, and even traveled to Wounded Knee after the massacre to help restore order. Cody made a fortune from his show business success and lost it to mismanagement and a weakness for dubious investment schemes. In the end, even the Wild West show itself was lost to creditors. Cody died on January 10, 1917, and is buried in a tomb blasted from solid rock at the summit of Lookout Mountain near Denver, Colorado. Evolution by Sherman Alexie Buffalo Bill opens a pawn shop on the reservation right across the border from the liquor store and he stays open 24 hours a day,7 days a week and the Indians come running in with jewelry television sets, a VCR, a full-length beaded buckskin outfit it took Inez Muse 12 years to finish. Buffalo Bill takes everything the Indians have to offer, keeps it all catalogued and filed in a storage room. The Indians pawn their hands, saving the thumbs for last, they pawn their skeletons, falling endlessly from the skin and when the last Indian has pawned everything but his heart, Buffalo Bill takes that for twenty bucks closes up the pawn shop, paints a new sign over the old calls his venture THE MUSEUM OF NATIVE AMERICAN CULTURES charges the Indians five bucks a head to enter. Response (Complete on a separate sheet of paper) 1. How would you describe the TONE of this piece? List two words/phrases/lines that help capture this tone: 2. Why do you think Alexie chooses to break the lines and stanzas where he does? Provide examples. 3. How does Alexie’s use of syntax (or lack thereof) affect the reading of this poem? Provide examples. 4. What is Alexie’s overall message in “Evolution”? 5. What does Alexie mean when he says, “The Indians/pawn their hands, saving the thumbs for last…”? (Lines 8-9). 6. How do you feel after reading this poem? Explain. How to Write the Great American Indian Novel By Sherman Alexie All of the Indians must have tragic features: tragic noses, eyes, and arms. Their hands and fingers must be tragic when they reach for tragic food. The hero must be a half-breed, half white and half Indian, preferably from a horse culture. He should often weep alone. That is mandatory. If the hero is an Indian woman, she is beautiful. She must be slender and in love with a white man. But if she loves an Indian man then he must be a half-breed, preferably from a horse culture. If the Indian woman loves a white man, then he has to be so white that we can see the blue veins running through his skin like rivers. When the Indian woman steps out of her dress, the white man gasps at the endless beauty of her brown skin. She should be compared to nature: brown hills, mountains, fertile valleys, dewy grass, wind, and clear water. If she is compared to murky water, however, then she must have a secret. Indians always have secrets, which are carefully and slowly revealed. Yet Indian secrets can be disclosed suddenly, like a storm. Indian men, of course, are storms. They should destroy the lives of any white women who choose to love them. All white women love Indian men. That is always the case. White women feign disgust at the savage in blue jeans and T-shirt, but secretly lust after him. White women dream about half-breed Indian men from horse cultures. Indian men are horses, smelling wild and gamey. When the Indian man unbuttons his pants, the white woman should think of topsoil. There must be one murder, one suicide, one attempted rape. Alcohol should be consumed. Cars must be driven at high speeds. Indians must see visions. White people can have the same visions if they are in love with Indians. If a white person loves an Indian then the white person is Indian by proximity. White people must carry an Indian deep inside themselves. Those interior Indians are half-breed and obviously from horse cultures. If the interior Indian is male then he must be a warrior, especially if he is inside a white man. If the interior Indian is female, then she must be a healer, especially if she is inside a white woman. Sometimes there are complications. An Indian man can be hidden inside a white woman. An Indian woman can be hidden inside a white man. In these rare instances, everybody is a half-breed struggling to learn more about his or her horse culture. There must be redemption, of course, and sins must be forgiven. For this, we need children. A white child and an Indian child, gender not important, should express deep affection in a childlike way. In the Great American Indian novel, when it is finally written, all of the white people will be Indians and all of the Indians will be ghosts. Response (complete on a separate sheet of paper) 1. List an example of figurative language used in this piece. What does it mean? How 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. does it affect the reader? What stereotypes does Alexie address in this piece? Did you notice the repetition of any words, phrases, or ideas? How does Alexie use sensory details? What sense is most prominent? Why? How would you describe Alexie’s TONE in this poem? Why? What do you think the final couplet of the poem means? Explain. How do you feel after reading this poem? On "Evolution" Buffalo Bill and the confiscation of culture by Benjamin Branham Pawn shops tend to represent sites of unorganized accumulation, places that gather anything and everything with the prospect of profiting from the vulnerability of others. By enticing patrons with quick cash--an instantaneous materialization of value--the pawn shop successfully confiscates living objects only to deprive them of meaning by re-offering them for sale. Sherman Alexie adapts this story poignantly in "Evolution." Alexie centers the enterprise of objectification in the figure of Buffalo Bill. Also known as William F. Cody (1846-1917), Buffalo Bill, no longer just an historical figure but rather an icon now synonymous with the American West, did at least his share in exploiting Native Americans. An honorary website credits him with helping "his West to make the transition from a wild past to a progressive future." The establishment of a binary between "wild" and "progressive" subjugates Indians by placing them in the role of savages, a representation that American history has repeatedly thrust upon them. Despite supposedly championing the rights of Indians, Buffalo Bill certainly contributed to their cultural confinement in his "Wild West" shows, performances that "contained elements of the circus, the drama of the times, and the rodeo," offering a "unique form of theatrical entertainment. The Wild West Show had as its theoretical aim the presentation of a pageant of the settling and the taming of the West" (Kramer 87). Beyond mere amusement, the shows also served as advertising campaigns to lure settlers to the West to help further tame the "uncivilized" region: The Wild West show was inaugurated in Omaha in 1883 with real cowboys and real Indians portraying the "real West." The show spent ten of its thirty years in Europe. In 1887 Buffalo Bill was a feature attraction at Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee. At the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893, only Egypt's gyrations rivaled the Wild West as the talk of Chicago. By the turn of the century, Buffalo Bill was probably the most famous and most recognizable man in the world. (American West) Given the legendary status history has accorded him, Buffalo Bill may be compared to other colonizing heroes in Western culture, especially those who circulated a dominant ideology as their role in enhancing domination. His ability to disseminate representations stems not only from his ubiquitous stage presence but also from the extensive publicity that presented his image. "Certainly no individual, before the days of movies and radio, ever had such effective personal exploitation. For nearly half a century he was continuously held before the public, in the pages of nickel and dime novels, on the boards in blood and thunder melodrama and in that astounding Wild West Show which toured from the tank towns to the very thrones of Europe" (Walsh 18). The title of a 1928 book, The Making of Buffalo Bill: A Study in Heroics, suggests that the phenomenon of Buffalo Bill was as much created by an eager audience as it was by Bill Cody. Its collective gaze, like the gaze performed by museum-goers, constructed an impervious ideal: "When they gazed upon the man himself they saw that he looked the part of hero" (Walsh 17). Empowered with the iconic eminence of a hero, Buffalo Bill possesses the capacity and authority to reproduce and distribute cultural myths. His conception of the "real West" extends from his imaginary relation to American ideals that have themselves been formed by such hegemonic historical representations as Manifest Destiny. The posters advertising Buffalo Bill (see below) contribute to the representational subjugation of Indians, portraying them as features of a crude land that the military must rehabilitate and civilize. The illustration depicts Buffalo Bill and his entourage riding in a "civilized" wagon through a tumultuous landscape. As the central focus, they marginalize the Indians on the borders of the painting, indeed cutting some of them off as they forcibly split the factions on both sides of their procession. The white riders stand taller than the encroaching Indians, a force that the advertisement construes as a threat to American progress. Such a hazard, the painting declares, must be vanquished by the collective gaze of American discourse, a gaze that restricts Native American culture to a territory of enclosure. In "Evolution," Alexie addresses the compartmentalization and commodification of culture by supplanting Buffalo Bill's stage antics with a business venture: Buffalo Bill opens up a pawn shop on the reservation Right across the border from the liquor store And he stays open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week And the Indians come running in with jewelry Television sets, a VCR, a full-length beaded buckskin outfit it took Inez Muse 12 years to finish. (1-6) Alexie re-appropriates history to fit the mold of a "24 hours a day, 7 days a week" contemporaneity. Placing it across the "border," rather than across the street from the liquor store, Alexie reminds us of the laws forbidding the sale of alcohol on many Indian reservations and the physical and cultural boundaries that continue to encircle them. The liquor store further calls attention to the use of alcohol as a device of suppression. Numerous historical accounts tell of white residents getting Indians drunk as a negotiation strategy to convince them to sign treaties that would yield land (Barr 7). The high rate of alcoholism that persists among Native Americans occupies a prominent position throughout all of Alexie's work. In "Evolution," Alexie intimates that the money the Indians obtain from pawning themselves evaporates when they cross the street to purchase liquor. This vicious cycle in which everyone stands to profit from Indians except Indians themselves sustains itself because "Buffalo Bill / takes everything the Indians have to offer, keeps it / all catalogued and filed in a storage room" (6-8). Buffalo Bill scavenges all he can, classifying it with the commodifying gaze of a museum curator. The cycle culminates in Buffalo Bill's move from collecting to exhibition: and when the last Indian has pawned everything but his heart, Buffalo Bill takes that for twenty bucks closes up the pawn shop, paints a new sign over the old calls his venture THE MUSEUM OF NATIVE AMERICAN CULTURES charges the Indians five bucks a head to enter. (11-15) By seizing the "heart" of the last Indian and subsequently closing the doors of the pawn shop, Buffalo Bill seals out the possibility of repossession. This act deprives the culture of its lifeblood. The new museum freezes "NATIVE AMERICAN CULTURES" in place, on display, behind glass cases. The painted over sign recalls the years of government manipulation of Indians in which new treaties invalidated old ones that the U.S. no longer wished to honor. The glossing over of old wounds and forms of cultural exploitation--feeding a people someone else's idea of what they should be--cap this poem with the absurd reality of a perverse history. Jane Tompkins comments on the manifestation of another absurd reality in her visit to a museum in Cody, Wyoming that enshrines Buffalo Bill himself. The existence of this memorial ironically shifts the position of the celebrated pioneer from curator to spectacle. However, unlike the cultural deprivation enacted by the museum of Alexie's poem, the Buffalo Bill Museum petrifies the superhero status of its namesake. Both instances cast a type of paralysis--The Museum of Native American Cultures frames its objects as an exhibition of a primitive culture, a display of dry bones; The Buffalo Bill Museum, as Tompkins tells us, galvanizes the golden image of an American icon: The Buffalo Bill Museum envelops you in an array of textures, colors, shapes, sizes, forms. The fuzzy brown bulk of a buffalo's hump, the sparkling diamonds in a stickpin, the brilliant colors of the posters--there's something about the cacophonous mixture that makes you want to walk in and be surrounded by it, as if you were going into a child's adventure story. It all appeals to the desire to be transported, to pretend for a little while that we're cowboys or cowgirls; it's a museum where fantasy can take over. In this respect, it is true to the character of Buffalo Bill's life. (Tompkins 530) The fantasy of Buffalo Bill's life is the fantasy projected onto it by the gaze of a hungry audience. For years Americans and viewers around the world stood captivated by the Wild West Show, feeding off its depictions of conquest, control, and violence. Tompkins gives us the severe yet appropriate metaphor that "museums are a form of cannibalism made safe for polite society," serving as venues that "cater to the urge to absorb the life of another into one's own life" (533). This remark accords with an attitude Alexie voices throughout his work. The dominant culture devours its subordinates to sustain its stance as an enforcer. "The objects in museums preserve for us a source of life from which we need to nourish ourselves when the resources that would normally supply us have run dry" (Tompkins 533). The act of sapping resources from another culture again points to the narrative of "Evolution," a title that drips with the irony of the concept of civilization. A civilized culture, Alexie implies, must "evolve" enough to perfect the practice of stealing and plundering other cultures for the purpose of presenting them as uncivilized behind the glass case of the museum. We too, Tompkins reminds us, are onlookers. "We stand beside the bones and skins and hooves of beings that were once alive, or stare fixedly at their painted images. Indeed our visit is only a safer form of the same enterprise" (533) rehearsed by Buffalo Bill's Wild West show--cultural objectification and destruction. Bibliography of Works Cited: "Buffalo Bill," The American West. 10 December 2000. <http://www.americanwest.com/pages/buffbill.htm>. Kramer, Mary D., "The American Wild West Show and 'Buffalo Bill' Cody," Costerus: Essays in English and American Literature, 4 (1972): 87-97. Tompkins, Jane, "At the Buffalo Bill Museum--June 1988," South Atlantic Quarterly 89.3 (Summer 1990): 525-545. Walsh, Richard J., The Making of Buffalo Bill, Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1928. Copyright © 2001 by Benjamin Branham On "How to Write the Great American Indian Novel" Beth Anne Palatnik Sherman Alexie has been published in the New Yorker. Alexie’s poem "How to Write the Great American Indian Novel" is linked with those New Yorker publications, and with Alexie’s welldocumented, unprecedented (at least for an American Indian writer) rise to fame, and with his second (or third, or fourth, after poet, novelist, and short story writer) career as Hollywood filmmaker. In other words, Alexie’s work has pop-culture capital, and "How to Write the Great American Indian Novel" in part responds to that perception of his work and is in part constructed by it. This poem, already problematized for aesthete critics because of its long, unwieldy lines, its sarcasm, and its subject, is a poem-that-is-not-really-a-poem about how to write a novel. But it is also a poem about the different ways to write like an American Indian. "The Great American Novel," of course, is more a pop culture catch phrase than an actual literary aspiration. After reading Philip Roth’s novel of that name, it’s impossible to take it seriously. But "the Great American Indian Novel"! One reading that thinks, "Ah! A new, emerging, cutting edge ethnic voice in American Literature! Why, it would be impossible, given the melting pot-salad bowlgrand mosaic that is America to write the Great American novel, but the Great American Indian novel could be done. And in fact, it should be done; America needs such a thing." Like other American Indian writers, Alexie points out the impossibility of making one writer or book "representative" of American Indian cultures. The mainstreaming of African-American literature, with Richard Wright’s Book-of-the-Month-Club Native Son, faced the same problem earlier in the century, and to some extent continues to face it today. But more than that, the poem’s injunctions are informed not by Literature, but by dime-store novels and spaghetti westerns. The images are Hollywood images – "half-breed," "horse culture." Alexie even plays with that most contemporary and fashionable of Hollywood images – "An Indian man can be hidden inside a white woman./An Indian woman can be hidden inside a white man." The Great American Indian novel, by Danielle Steele – why not? This poem bodice-rips right along with her. A recent profile of Alexie in Utne Reader (Sept./Oct. 2000) quotes him as saying, "In order for the Indian kid to read me, pop culture is where I should be…I’d rather be accessible than win a MacArthur." He imagines his ideal audience as "rez" kids, like himself. Alexie comes across as flippantly cynical about his success, and the way his Indian heritage has played into that success – "It’s a crowded world out there, and everybody is clamoring for attention, and you use what you’ve got…And what I’ve got that makes me original is that I’m a rez boy" (72). Those imagined "rez boys" seem genuine, but also, to some extent, Alexie’s evocation of them is deliberate spin. He displays the requisite shame at being part of pop culture – so vulgar! So common! – and offers the requisite justification: it’s for the children. A few lines from "How to Write the Great American Indian Novel" undercut this bit of masking: "There must be redemption, of course, and sins must be forgiven./For this, we need children. A white child and an Indian child, gender/not important, should express deep affection in a childlike way." The poem hollows out this form of redemption; in the interview, Alexie uses it to misdirect. The Utne Reader article describes two photographs of Alexie, one with what he calls "the ethnic stare," and one "without the mask." Alexie not only uses pop culture – he abuses it. Letting the audience of his latest book see him "without the mask" spins even more subtly the image of the American Indian of letters; if they believe they glimpse something personal, if they think that they know him, his persona is cemented – as it is for the author of this article – by a perceived appeal to the universality of man. Pop culture not only reaches more people than so-called high culture, it does different things than high culture. The construction of pop culture includes "general," widespread appeal – bestseller lists, Oprah’s choices, for example – and a predisposition towards enjoyment. A Danielle Steele novel is, according to this paradigm, more "fun" than Moby Dick. By associating himself with these expectations, Alexie can do more than reach a wider audience. He can open up the definition of pop culture to include American Indian works – thereby bringing bestseller readers’ attention to the people that a collective American unconscious have chosen to shunt off and forget. Alexie reads and re-forms pop culture so adeptly, in fact, that marvel has been directed almost exclusively at his persona, and to a lesser extent on how much fun his work is. Meanwhile, he subtly redirects markers of difference so that the political implications of his work hit on that pop-culture-forming American unconscious. Changing pop culture reaches not only rez boys – though that would be nice – but people who watch movies and read bestsellers and subscribe to the New Yorker. In Alexie’s hands, pop culture is a tool, a means to accessibility, a way to get read – but his use of pop culture represents not just a call to and a chance to influence a larger audience, but an area of contention within itself, engaging like nothing else with the concept of the "native." Along with the collective American unconscious, the concept of pop culture contains the image of a wellspring of visceral, internal truth – the same thing that the unsatisfactory permutations of "the Great American Indian novel" attribute to the American Indian. The poem critiques this conception of popular culture as much as it critiques the representations of American Indians within it – and for the same reasons. The poem addresses itself as much to American Indian writers seeking to "tell their story!" as it does to stereotypes held by white people. Even if Alexie were to write it, he implies, he would fall into those traps. He’d like to write it, though; in each line of the poem, as he inveighs against Hollywood stereotypes of American Indians, we know he would do it differently. "Smoke Signals," Alexie’s first film – screened at the Sundance Film Festival – could be read as The Great American Indian Road Movie. Its two main characters steep themselves in pop culture, both embodying stereotypes – one the stoic, the other the visionary – and showing witty awareness of them. The ethnic face is a mask, and a tool, but it is also, for Alexie, inescapable. Despite the creation of a persona who has "traded" on his Indian heritage to attract media attention, the accessibility of Alexie’s work depends on his embrace of that situation. For him, it is a matter of representing rather than being represented; the people in the Great American Indian Novel may not reflect his authorship any further than that. But "when it is finally written,/all of the white people will be Indians and all of the Indians will be ghosts." So this novel will be written – not the Great American Indian novel that Alexie might like to write, but novel after novel of earthy Indian healers, men who smell like horses and awake uncontrollable other-lust in white women. But if this representation is not the "right" one – and it’s clear from Alexie’s sarcasm that it isn’t – can there be proper representations of American Indians in literature? It may depend on by whom and to who the Indians are represented. Alexie would like his work to be accessible, and it is. But this poem wonders if that accessibility always has to come with a Hollywood ending, and what happens if it doesn’t. He can change that Hollywood ending, reach into the pop culture unconscious, and begin to recreate the image of the American Indian along with its double bind. But can the Great American Indian Novel be more than just a pop culture joke? And if it could, would anyone read it? And if no one read it, what would be the use of writing it? Pop culture may be a tool and a weapon, but Literature lasts. Alexie enters the Indians into the debate about the Great American Novel, pulling them into the question of American identity, reminding his audience – surely not only rez boys – that any novel claiming to be "American" must engage with the Indian in itself. But he wonders, and rightly, how far that injunction can extend. The Indians, in any work aimed at mass culture (Alexie wants to aim his work at mass culture; he wants to make money and he wants people to read what he writes), may be ghosts. They may, quite literally, be ghosts: the Indians are starving to death, as he points out elsewhere in his essays. If attention isn’t drawn to them – not only to their beautiful shields, but to their alcoholism, their poverty, their early and frequent deaths ("There must be one murder, one suicide, one attempted rape./Alcohol should be consumed. Cars must be driven at high speeds.") – they will, by the time anyone gets around to writing about them, be dead. The lyric speaker of Alexie’s "Indian Boy Love Song (#2)" has a complex relationship to oral culture (embodied in that poem, as it frequently is elsewhere, in the tongues and chests and hearts of women). He asks forgiveness from the women for his distance from them, asking that he be forgiven for not being Momaday – for not celebrating American Indian culture in appropriate ways. But those tongues and hearts, Alexie implies, don’t last. The chests are thin. The stories of the old women won’t last long. But if he writes them down – the stories about the old women as well as their folk tales and songs – they’ll live on. But then how can he sell that to the critic sitting in the stands at the powwow, eating his hot dog?