Criminal Procedure – Levenson (2012) (4)

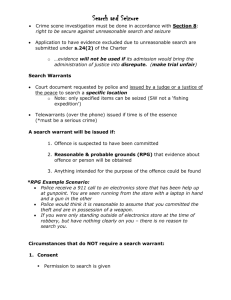

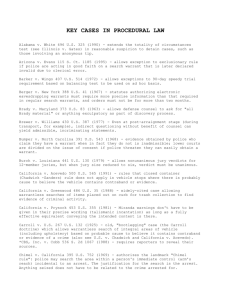

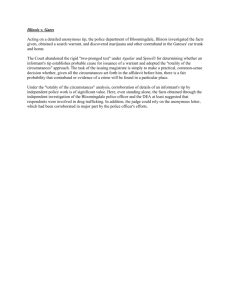

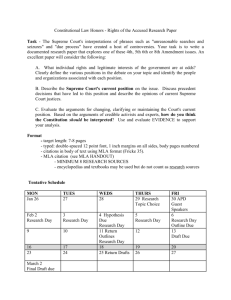

advertisement