Nowlin 2003 - University of Mississippi Law School Student Body

advertisement

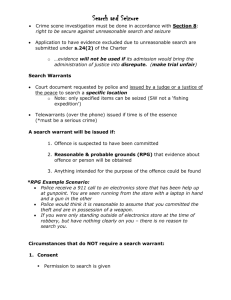

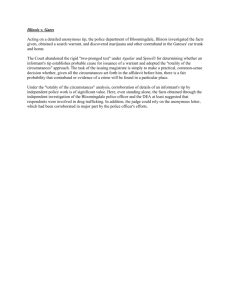

Criminal Procedure (Nowlin, Fall 2003) I. Overarching policy issues in criminal procedure A. Substantive policy dimension 1. “Crime control” model A. “(R)epression of crime is the most important domestic goal of government.” (Understanding Criminal Procedure, Joshua Dressler) B. Focus efficiency of convictions 1. Advocates prefer no judicial processes to formal 2. Police officers permitted substantial opportunity to function free of legal impediments C. Favors uniformity 1. Procedures must be “routine” and “stereotyped” to handle large numbers of cases] D. Presumes guilt of suspects 1. “Almost all criminal Ds are, in fact, guilty.” (Dershowitz) E. “The Crime Control model sees the efficient, expeditious and reliable screening and disposition of persons suspected of crime as the central value to be served by the criminal process.” (Packer, The Courts, The Police, and the Rest of Us [1966]) 2. “Due process” model A. Focus on the rights of accused; human rights; dignity; fear of government tyranny 1. More likely to favor interests of individual over community 2. Questions reliability of informal processes; believes in early intervention of lawyers, judges A. Instead of “conveyor belt” comparison of “crime control model,” “due process” model more like an obstacle course. 3. Focuses on doctrine of legal guilty -- must prove beyond a reasonable doubt 4. “The Due Process model sees (criminal convictions) as limited by and subordinate to the maintenance of the dignity and autonomy of the individual.” (Packer, supra) B. Structural dimension of criminal procedure 1. Restraint in judicial power (in line with “crime control” model) A. Deference to democratic decision-makers (Legislatures) B. Separation of powers; federalism 1. Local governments may want more flexibility in crime control 2. Strive to minimize judiciary’s political discretion C. Required to ground decisions very firmly in traditional legal materials D. Supreme Court in the 1980s 2. Activism in judicial power ((in line with “due process” model) A. More free to implement broader constitutional values B. To prevent discrimination of majority over minority C. Exercise substantial amount of political discretion in determining constitutional provisions C. Supreme Court in the 1960s 1. Started federalizing criminal procedure C. Supreme Court today 1. Conservatives (“crime control” and “restraint”) A. Rehnquist, Thomas, O’Connor, Kennedy, Scalia 2.. Liberals (“due process” and “activism”) A. Souter, Stevens, Ginsberg, Breyer 3. NB Rule of 5 A. Five votes can do anything D. Limits 1. Done on case-by-case basis -- piecemeal 2. Coherence -- what a case means and how it does, or doesn’t, line up with other cases 3. Implementation II. Incorporation A. Duncan v. Louisiana (391 U.S. 145, 1968) 1. IMPORTANCE: “Because we believe that trial by jury in criminal cases is fundamental to the American scheme of justice, we hold that the 14th Amendment guarantees a right of jury trial in all criminal cases which--were they to be tried in federal court--would come within the Sixth Amendment’s guarantee.” (White) A. Incorporated Sixth Amendment to state practice 2. D was convicted without a jury trial in Louisiana on a simple battery charge (max. penalty of two years, $300 fine). D wanted a jury, and Supreme Court held that the jury trial was “fundamental to the American scheme of justice” in such a crime. A. NB That if it were a less serious offense carrying only a penalty up to six months in prison, a jury trial is not mandated. B. NB Does not affect waivers 3. Fourteenth Amendment (Section 1) A. “All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” B. Approaches to incorporation 1. Fundamental fairness (fundamental rights) doctrine (advocate: Justice Harlan, who dissents in Duncan) A. Asserted first in 1884, theory asserts due process clause is not a reflections of the provisions of the Bill of Rights B. Rights are only protected if “(t)o abolish them is…to violate a ‘principle of justice so rooted in the traditions and consciences of our people as to be ranked as fundamental.” (Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U.S. 319, 1937) C. Objection (as stated by Justice Black) 1. Too subjective and not limited to Bill of Rights 2. Total incorporation (judicial architect: Justice Black) A. “(O)ne of the chief objects that the provisions of the (14 th) Amendment’s first section, separately, and as a whole, were intended to accomplish was to make the Bill of Rights applicable to the state.” (Black) B. a “due process” incorporation C. All rights in the first eight amendments should be incorporated 3. Selective incorporation (advocate: Justice White) A. Current theory B. Compromise: rights are those of “fundamental fairness” in addition to the enumerated in the Bill of Rights. 1. What’s something that’s fundamentally fair? A. Can’t have coerced confessions; must prove every element beyond a reasonable doubt III. Fourth Amendment A. Rise and Fall of Boyd v. United States, 116 U.S. 616 (1886) 1. Fourth Amendment tied to physical intrusion--trespass--into constitutionally protected area. A. SUMMARY: D was forced to turn over papers on imported plate glass to prosecutor. Court holds violates Fourth and Fifth amendments. 1. Gov’t must have superior possessory interest to seize under Boyd A. EXAMPLES 1. Papers that gov’t requires D to keep A. Hale v. Henkel 201 U.S. 43 (1906) 1. Boyd analysis doesn’t apply to corporations. B. Shapiro v. United States 35 U.S. 1 (1948) 1. Required records doctrine 2. Stolen goods 3. Contraband 4. Criminal instrumentality 1. Maron v. United States (275 U.S. 192, 1927) A. Distinguished between instrumentality and mere evidence B. Gould v. United States 255 U.S. 298 (1921) A. Applied Boyd analysis to hold gov’t can’t just search for “mere evidence” 2. Two clauses of Fourth Amendment A. Clause 1: Reasonableness 1. Under Boyd, it is unreasonable to force D to turn over papers that are incriminating (NB close tie between Fourth and Fifth amendments) B. Clause 2: Probable cause / warrants 3. Olmstead v. United States, 277 U.S. 438 (1928) A. Under Boyd, FBI didn’t violate D’s Fourth Amendment rights by tapping telephone wire outside of home. Conversation not protected (speech is not property) by Fourth and no physical intrusion. 4. Rejecting Boyd A. Schmerber v. California, 384 U.S. 757 (1966) (BRENNAN) 1. Court holds intrusion of D to get blood test is not a violation of Fourth A. Court rejects property analysis, holds Fourth is about privacy B. Due to exigency, blood test needed to avoid losing dissipating BA level 1. Only minor intrusion and warrant delay would have hindered 2. Test for reasonableness A. Have probable cause and search warrant B. Have probable cause and exigency 2. NB Fifth Amendment challenge by D rejected too A. Court holds only testimonial or communicative (not blood test) protected B. Warden v. Hayden, 387 U.S. 294 (1967) (BRENNAN) 1. Rejects mere evidence rule 2. Under privacy analysis, search for mere evidence constitutional if probable cause requirements met. Further distinction between “privacy” and “property” A. “Privacy is disturbed no more by a search directed to a purely evidentiary object than it is by a search directed to an instrumentality, fruit, or contraband.” 3. Dissent (DOUGLAS) A. citing Learned Hand, “(T)he real evil aimed at by the Fourth Amendment is the search itself…If the search is permitted at all, perhaps it does not make so much difference what is taken away, since the officers will ordinarily not be interested in what does not incriminate…Nevertheless, limitations upon the fruit to be gathered tend to limit the quest itself.” B. Threshold of Fourth Amendment (SEARCH) 1. What is a search? A. Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347 (1967) (STEWART) 1. SUM: D transmitting wager information over telephone. Gov’t used electronic devices to listen in (tape recorder on phone booth). Court holds violates Fourth. REJECTS Boyd analysis, and applies privacy analysis. 2. “(T)he Fourth Amendment protects people, not places.” A. Is there a reasonable expectation of privacy, thus meaning Fourth applies and gov’t needs probable cause/warrant or probable cause/exigency B. TEST FROM HARLAN’S CONCUR 1. Subjective prong -- actual expectation 2. Objective prong -- is the expectation one society recognizes as legitimate, justifiable and reasonable A. Empirical prong: look at facts around you B. Normative value test 1. Social value of privacy rights asserted 2. Degree of intrusion 3. What efforts taken to protect privacy 4. Importance to police C. Dissent (BLACK) 1. Fourth doesn’t apply to eavesdropping B. United States v. White, 401 U.S. 745 (1971) (WHITE) 1. False friend A. SUM: Court holds D assumes risk person on other end of phone will tell gov’t. Not a violation of Fourth. B. What a person knowingly exposes to the public, there is no protection 2. Hoffa v. United States, 385 U.S. 293 (1966) A. Undercover agents getting info. from D not a violation 3. NB Shift from “reasonable expectation” to “possible risk of disclosure” C. Smith v. Maryland, 442 U.S. 735 (1979) 1. Court holds use of pen register to record numbers dialed from private residence is not a search 2. Distinguish “content” from Katz analysis from only numbers dialed D. Bond v. United States, 120 S.Ct. 1462 (2000) (REHNQUIST) 1. Court holds police can’t “squeeze” luggage on bus in exploratory manner A. Contrast: here, physical intrusion; Ciraolo and Riley, infra, only visual B. Dissent (BREYER, SCALIA) 1. Squeezing foreseeable by other passengers; tying purpose of squeeze to 4th Amendment 2. No reasonable expectation of privacy with luggage on bus 2. United States v. Place, 462 U.S. 696 (1983) A. Not a search to have drug-sniffing canine come up to luggage in public place E. Searches in other contexts (from handout) 1. Air Pollution Variance Board v. Western Alfalfa Corp. (1974): daylight visual observation of smoke plumes from open fields of respondent’s property not a search and seizure 2. Rakas v. Illinois (1978): automobile passenger has no legitimate privacy interest in unlocked glove compartment or area under front seat 3. Hudson v. Palmer (1984): prisoner has no legitimate privacy interest in prison cell; Fourth Amendment not applicable within confines of cell 4. New York v. Class (1986): automobile owner has no legitimate privacy interest in vehicle identification number. 5. California v. Greenwood (1988): Looking into garbage placed in opaque containers and left for collection at curb at end of driveway not a violation of search and seizure 6. United States v. Jacobsen, 466 U.S. 109 (1984): Police can replicate a private search if by doing so learn nothing new A. Someone finds container, opens it, finds drugs, closes it and gives to police and tells police what is inside. B. Must look to totality of the circumstances to determine whether acting at behest of police C. Open fields doctrine 1. Fourth Amendment does not protect an open field A. Curtilage is protected (yard of home) 1. Why not protect? A. Textual analysis 1. “Open fields” not part of Fourth Amendment language B. Katz test 1. Property right not determinative of privacy right A. Go through the empirical and normative tests 1. “Open fields do not provide the setting for those intimate activities that the Amendment is intended to shelter from government interference or surveillance.” (J. Powell) B. Oliver v. United States (466 U.S. 170, 1984) (POWELL) 1. Court holds field about one mile from Oliver’s home is not protected by Fourth Amendment, and police who found marijuana there did not conduct a “search” as defined in Amendment Open field w/ marijuana Home Curtilage 2. Bright-line rule A. Once designated an open field, not protected by Fourth Amendment 3. Dissent (Marshall) A. Dismisses textual analysis, pointing out Katz prevents “search and seizure” of taped telephone conversations at phone booth, which is not explicit in Amendment B. Offer three-prong objective test for why this open field is protected 1. Expectation of privacy (owner of property expects such) 2. Nature of use (could use for solitary walks, religious ceremonies) 3. Precautions (posted no trespass sign) C. Contrary rule of law 1. Can’t trespass to search, otherwise giving police blessing to break law to get information 4. Four-part test to determine where curtilage stops and field begins (from United States v. Dunn, 480 U.S. 294, 1987) A. Proximity to house B. Enclosure (a hedge, trees) C. Nature of the use for which land is put D. Precautions (how high is the fence?) C. California v. Ciraolo (476 U.S. 207, 1986) (BURGER) 1. Court holds no search for police using airplane to fly over property--fenced off from a ground-level view--to see marijuana plants A. Fourth Amendment does not require “police traveling in the public airways at this altitude (1,000 feet) to obtain a warrant in order to observe what is visible to the naked eye.” B. Key that police used a normal camera available to general public 1. Contrast with Kyllo v. United States (121 S.Ct. 2038, 2001) A. Court strikes down search with thermal-imaging device aimed at a private home from public street with technology not in general public use and information not otherwise obtainable without physical intrusion C. Dissent (Powell) 1. Violates empirical test (individual had expectation of privacy) 2. Violates normative test A. Had fences to guard 2. Florida v. Riley, 488 U.S. 445 (1989) A. Helicopter used to see marijuana not a search as long as fly at legal FAA limit (plurality held); here 400 feet was legal D. Threshold of Fourth Amendment (SEIZURE) 1. Of Property A. Meaningful interference with a possessory interest 2. Of Person A. Police handcuff, restrain, shoot you B. Seizure has to be intentional (Brower v. Inyo County (1989)) 1. Can have transfer intent -- try to shoot someone but shoot B; B is seized. C. Three ways: 1. Requires touching 2. Says “not free to leave” 3. Involves a police weapon (pointing at you) 3. United States v. Mendenhall (1980) A. Totality of the circumstances test (“fuzzy test”) for seizure Reasonable person would believe he is not free to go. 1. Policy (crime-control) -- want police to be able to talk with people without every conversation being a “seizure” B. Court says person in airport stopped by officers who find her suspicious would reasonably feel free to leave when police stop to ask her questions, and ask her to come to office; officers had given her back ticket and license before asking her to come with them. 1. Need more for seizure as part of totality of circumstances test A. Florida v. Royer (1983) 1. Suspect in airport was seized when officers took ticket, license, said they suspected him of drug trafficking, asking him to come to a police room with them and didn’t indicate he was free to leave. C. Applying Mendenhall in confined space 1.Florida v. Bostick (1991) A. Court holds there is no per se rule that questioning on a bus by police is a seizure. B. Reasonable for bus passenger to decline officer’s request or otherwise terminate encounter 1. Test no longer feel free to leave, but feel free to decline and terminate C. Dissent (Marshall) 1. Noted officer’s gun as intimidating; bus passenger couldn’t leave D. Seizure requires physical restraint or submission to officer’s request 1. California v. Hodari D. (1991) A. Court holds youth who runs from police chasing him is not seized until physically tackled by police. 1. No seizure until submission to officer’s request to stop or physical touching. B. Policy -- Want to encourage compliance with police; another reason, look to common law for when there’s an arrest 4. Exclusionary Rule (in its Fourth Amendment context) (see notes, infra) A. Weeks v. United States (1914) 1. Applied exclusionary rule to evidence in federal cases 2. Reasoning A. W/o exclusionary rule, Fourth Amendment would be right without a remedy B. Judicial integrity -- don’t want to be complicit in constitutional violation B. Mapp v. Ohio (1961) 1. Applied exclusionary rule to states (overrules Wolf v. Colorado, 1949, which held e/r rule didn’t have to apply to states) 2. Reasoning (adding to Weeks) A. DETER police violations 3. Dissent (Harlan) A. Court wrong to impose e/r on states (fettering unnecessarily) C. Arguments on Exclusionary Rule 1. Pro A. Deterrence of bad police conduct 1. Prosecutors weren’t going to prosecute for violations B. More teeth than a civil claim for violation 2. Against A. Protects criminals B. Other remedies outside of exclusion available (fines) E. Unreasonableness and Probable Cause in Fourth Amendment 1. Two clauses in Fourth Amendment A. Clause 1: reasonable 1. Guarantees right to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures 2. Probable cause is required as a condition of warrantless searches and seizures A. Want to encourage use of warrants B. If less than p/c needed for warrantless searches and seizures, little incentive to get warrants B. Clause 2: warrant / probable cause (see notes, infra) 1. Probable cause must be based on more than mere suspicion 2. Probable cause to search exists if the facts and circumstances within (the officers’) knowledge and of which they (have) reasonably trustworthy information (are) sufficient in themselves to warrant a man of reasonable caution in the belief than ‘an item subject to seizure will be found in the place to be search.’ 2. First test to determine probable cause for warrant A. Spinelli v. United States (1969) 1. Two-prongs A. Veracity 1. Looked at independently for truthfulness 2. Oath; affirmation; “I swear” by the officer 2. For informant, veracity of informant (reliability) B. Basis of knowledge 1. Facts showing how come upon information supplied for warrant 2. Is it first-hand? 3. Second-hand tip? A. Are there self-verifying details? B. If not self-verifying, is there corroboration? C. If not corroboration, add to rest of mix 3. Illinois v. Gates (1983) A. Case overrules Spinelli test, incorporating Spinelli into totality of the circumstances test B. Question -- Would a reasonable person think there is a substantial basis for a warrant? C. While both prongs of Spinelli are included, one can outweigh what’s lacking in another D. Policy 1. Test less rigid than two-prong; less complex; encourages police to get warrants because less rigid than Spinelli E. Problem: 1. Balancing test has flaw -- liar (the basis of knowledge) can tell someone else (veracity for warrant) a lie; the veracity prong can’t make up for basis of knowledge prong 4. Review of appellate courts of warrant’s validity A. Warrant searches -- deferential B. Warrantless searches -- de novo 5. Pre-textual stops A. Whren v. United States (1996) 1. Subjective state of mind of officer is irrelevant if there is probable cause someone committed a traffic offense; police can stop even if officer really wants to look for drugs as long as there was a traffic offense to base stop on. 2. Per se reasonable. Reasonable officer would stop someone after traffic offense. A. Even if there is racial profiling, not a Fourth Amendment violation--Equal rights complaint. B. Related case -- full custodial arrest for minor offense permitted 1. Atwater v. Lago Vista (2001) F. Unreasonableness and warrants 1. Deals with Clause 2 2. Policy for warrant requirement A. Checks on overzealousness of police who might see p/c when there is none B. Avoids hindsight problems (magistrate seeing there is drugs on warrantless search and letting that influence his decision on probable cause) C. Reasonableness in clause 1 is defined by clause 2 warrant requirement 3. Application for warrant A. Police issue affadavit with oath / affirmation 1. “detached and neutral” magistrate makes decision of p/c 2. Invalidating warrants A. Franks v. Delaware (1978) 1. Three-prong test: A. Affiant fabricated evidence B. Affiant knowingly and intentionally fabricated C. False statement necessary to finding p/c. B. Particularity requirement 1. Warrant must specify “where and what” (reasonableness standard) 4. Execution of warrants A. Concern for staleness (Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure state 10-day rule to execute) 1. Reasonableness test (there is no bright-line constitutional requirement) B. Nighttime warrants 1. Unreasonable in most states to execute at night, unless “reasonable” justification C. Means of entry 1. Knock-and-announce required unless exigency A. Wilson v. Arkansas (1995) 2. Only need “reasonable suspicion” to not knock-and-announce A. Richards v. Wisconsin (1997) D. Damage to property 1. Can do “reasonable damage” but not allowed to do “unreasonable damage” in executing warrant A. United States v. Ramirez (1998) 5. Exigency (situations of hot pursuit, escape of suspects, destruction of evidence, danger to officers) A. Exigent circumstances can give police right to search without a warrant 1. Warden v. Hayden (1967) A. Scope of the exigency determines the scope of the search. Once exigency disappears, so does warrantless search ability B. When there’s insufficient exigency 1. Welsh v. Wisconsin (1984) A. Exigent-based warrantless search no good for police looking for minor offense suspect (DUI suspect who had passed out inside his home) C. Police can’t create exigent situation 1. Vale v. Louisiana (1970) D. Temporary seizure until warrant obtained 1. Illinois v. McArthur (2001) A. As woman escorted from premise following domestic disturbance call, she says drugs inside with guy. Police can keep guy on porch and temporarily seize until warrant arrives. G. Automobile Exception (bright-line exception) 1. Carroll v. United States (1925) A. Automobiles and other conveyances may be searched without a warrant…provided that there is probable cause to believe that the car contains articles that the officers are entitled to seize. 2. Can warrantless search impounded car too if there is probable cause A. Chambers v. Maroney (1970) 1. Safer to search at stationhouse; more thorough 3. Policy for auto exception A. Ready mobility of cars B. Diminished expectation of privacy in cars 1. Cars generally exposed to public view 2. Autos heavily regulated 3. Public roads in plain view 4. More contact with police in car than in home 5. Personal effects kept in house, not cars 6. If in accident, auto contents exposed C. Lesser intrusion to search without warrant than to seize and wait for warrant. 4. California v. Carney (1985) A. No special exception for mobile homes to auto exception B. Test is TOTALITY OF THE CIRCUMSTANCES 1. If car is readily mobile based on observation of reasonable officer, then it’s subject to auto exception 2. When would a vehicle not be? A. Missing battery; tires C. NB: If car within driveway, within curtilage (hint: car to be in public to be subject to warrantless search) H. Containers and cars 1. United States v. Chadwick (1977) A. Greater privacy interest in containers than cars (need warrant to search) B. Police may seize, then get warrant to search C. NO CONTAINER EXCEPTION 2. When container is in car, and there is probable cause to search container only (overruled, see notes, infra) A. Arkansas v. Sanders (1979) 1. No warrantless exception; only search with warrant 2. Mere fact put in car does not diminish privacy expectation 3. When there is p/c to search car, and container inside A. United States v. Ross (1982) 1. Can search container in the car if it could contain what there is p/c to look for in car (here, container was a crumbled paper bag) 4. Overruling Sanders A. California v. Acevedo (1991) 1. Package suspected of having marijuana subject to warrantless search 2. Policy A. less intrusive (otherwise, if police can’t search only container in car, police would want to search entire car) B. Old rules too confusing 3. Does it matter who container belongs to? A. NO. Wyoming v. Houghton (1999) NO W-EX Chadwick No container exception WARRANT EXCEPTION (MODERN RULE) Acevedo Ross When PC for container inside of car When PC for car that has container Chambers When PC for car I. Warrant preference and seizure of person 1. United States v. Watson (1976) A. Police do not need warrant for felony arrest of person in public B. Only need warrant to arrest of misdemeanor not seen by officer 1. If within officer’s five senses, no warrant needed C. Traditionally, warrants not needed for such seizures 2. If warrantless seizure, prompt judicial determination of probable cause must be made (within a reasonable amount of time) A. Gerstein v. Pugh (1975) (called Gerstein hearing) B. 48 hours considered reasonable J. Search incident to arrest 1. Chimel v. California (1969) A. Police allowed to do contemporaneous search of person’s “wingspan” in making a custodial arrest (also called “grabbing area”) 1. What is grabbing area? Possibilities: A. One-room rule B. “Wing span” of several feet B. Policy 1. Officer safety 2. Preserve evidence that might otherwise be destroyed 2. Search incident to traffic stop and arrest A. Search flows automatically (only need quantum of suspicion to do search; no need for particularized suspicion) 1. United States v. Robinson (1973) 3. Search of automobile incident to arrest A. New York v. Belton (1981) 1. Search incident to arrest of passenger compartment of car permitted; interior of car A. Excludes trunk B. Don’t confuse w/ auto exception 4. No search incident to citation A. Knowles v. Iowa (1998) 1. If only citing, not same high-intensity situation as full custodial arrest 2. Problem: Officer may say person “under arrest,” search, find nothing and then let go with citation 5. Protective sweeps A. Maryland v. Buie (1990) 1. Police may, as search incident to arrest, automatically without p/c or reasonable suspicion, look in closets and other spaces immediately adjoining place of arrest from which an attack could be immediately launched 2. Need reasonable suspicion to go beyond area of automatic sweep 3. Policy: safety of officers K. Entering private residence 1. Payton v. New York (1980) A. Need arrest warrant to enter / but do not need search warrant 1. Need PC suspect is there in addition to probable cause B. Policy 1. Derivative privacy protection to home by requiring arrest warrant and pc for arrestee 2. Steagald v. United States (1981) A. If arrest warrant is for person in third-parties house, NEED search warrant to enter 1. Privacy interest of homeowner is greater L. Inventory searches 1. Policy A. Keep out dangerous instrumentalities introduced to police station B. Prevent false claims C. Help ID D. Prevent theft of property 2. Only looking to clause one (reasonable) to balance state interest vs. individual interest A. Must be standard operating procedure 1. Routine 2. Administrative (not investigative) A. Subjective intent does matter if not administrative B. If find too much discretion to routine, may find invalid search B. Must be in custody C. Incarceration must what follows arrest 3. Illinois v. Lafayette (1983) A. “(I)t is not ‘unreasonable’ for police, as part of the routine procedure incident to incarcerating an arrested person, to search any container or article in his possession, in accordance with established inventory procedures.” 4. Colorado v. Bertine (1987) A. Permissible to either impound and inventory search car or decide to park in open lot as long as part of (1) routine and (2) administrative process 1. Can search glove compartment M. Consent searches 1. Schneckloth v. Bustamonte (1973) A. Consent to search is NOT a 4th Amendment waiver issue 1. No notification to D of right to refuse is required B. Voluntariness is based on totality of circumstances 1. It’s reasonable to search with consent C. Policy: Crime control (notes, supra) 2. Ohio v. Robinette (1996) A. Fourth Amendment does not require that a lawfully seized person be advised that she is free to go before her consent to a car search will be recognized as voluntary 1. Voluntariness based on totality of the circumstances B. Policy: Crime control 1. DISSENT (Stevens): Was an illegal detention --traffic stop over 3. Scope of consent A. Florida v. Jimeno (1991) 1. Scope of consent based on reasonableness of given consent to officer’s understanding A. What officer reasonably believes to be scope 4. Illinois v. Rodriguez (1990) A. Warrantless entry of residence is valid when it is based on the consent of a person who police believe, incorrectly but reasonably, has authority to grant consent B. Test: “(W)ould the facts available to the officer at the moment…warrant a man of reasonable caution in belief that the consenting party had authority over the premises?” N. Plain View Doctrine 1. Warrant exception for seizures A. Officer has to lawful vantage point B. Has right of access to seize object (no 4th Amendment violation) C. Seizable nature of object has to be immediately apparent 2. Applies anytime officer engaged in lawful activity O. Stop and Frisk 1. Terry v. Ohio (1968) A. Stop is a seizure, but less intrusive 1. Elements to look at to test whether just stop or more: A. Level of restraint (handcuffs?) B. Spacial component (forced movement?) C. Temporal component (can’t keep too long?) B. Frisk is a search, but less intrusive 1. Pat down over clothing (only go into pockets if feel weapon that comes into plain view) A. If feel something and don’t know what it is, can take out 2. Must be immediate and automatic C. Need REASONABLE SUSPICION for stop and frisk 1. TEST: Officer point to specific, articulable facts that lead to reasonable suspicion that criminal activity may be afoot and suspect may be armed and dangerous D. Policy: officer safety 2. Defining reasonable suspicion A. Illinois v. Wardlow (2000) 1. Objective (totality of the circumstances) test A. Individualized suspicion B. Articulable suspicion 1. Specific facts / rational inferences 2. In this case: A. High crime area + flight = reasonable suspicion B. Alabama v. White (1990) 1. For reasonable suspicion from anonymous tip, test is Gates’ totality of the circumstances A. Veracity of tip (corroboration) B. Basis of knowledge 1. Predictive information (self-verifying details) C. Florida v. J.L. (2000) 1. Anonymous tip young black male has gun under plaid shirt at street corner is not enough to establish reasonable suspicion. A. Not enough predicative information; no corroboration D. Michigan v. Long (1983) 1. Allowing a Terry search of a vehicle A. Police can “frisk” passenger compartment of car if reasonable suspicion suspect is dangerous and may gain immediate control of weapons. 2. RELATED A. Pennsylvania v. Mimms (1977) 1. Once car pulled over, police can ask driver to alight from vehicle. A de minimis intrusion. 2. Maryland v. Wilson (1997) A. Passengers may be asked to step out of vehicle too. 1. Still no individualized suspicion, but officer safety outweighs privacy interest B. Unclear if can forcibly detain for entire duration of stop E. Ybarra v. Illinois (1979) 1. “(A) person’s mere propinquity to others independently suspected of criminal activity does not, without more, give rise to probable cause (or reasonable suspicion) to search that person.” 2. FACTS: Warrant to search bar, bartender, but not Ybarra meant police couldn’t search Ybarra without more (no reason to believe Ybarra armed and dangerous) 3. NB Both probable cause and reasonable suspicion are “totality of the circumstances” test 4. Michigan v. Summers (1981) A. Police searching a premises with valid warrant for contraband may DETAIN an occupant or resident of the premises during the search 1. Don’t want occupant to get weapon (or take evidence out) 2. Detain for potential arrest 3. NB: If searching for only mere evidence, may have less connection between warrant and third party occupant 4. Don’t forget: police can just ask for consent, or ask people to leave (it’s a seizure of premises) B. BASIC RULE: Can detain occupant; resident; in public places, probably can’t detain absent individualized suspicion. P. Special needs searches 1. Sobriety checkpoints not unconstitutional A. Michigan Dep’t of State Police v. Sitz (1990) 1. Use balancing test to find police can stop for drunk drivers (test from Brown v. Texas (1979)). A. Public interest (stop drunk drivers) B. Does seizure advance state interest (is it effective?) C. Liberty interest 2. Policy A. Checkpoint stops everyone / no surprise B. CONTRAST 1. Delaware v. Prouse (1979) A. RANDOM stops of drivers is unconstitutional B. Officer was stopping to do random license and registration checks 1. Dicta in opinion suggests checkpoint for similar programmatic activity would be OK 2. Narcotics checkpoint is unconstitutional A. City of Indianapolis v. Edmond (2000) 1. Since primary purpose of stop was general crime fighting, then need individualized suspicion 2. “(P)rogram driven by an impermissible purpose may be proscribed while a program impelled by licit purposes is permitted even though the challenged conduct may be outwardly similar.” A. Some call a “magic word” case 3. This is a programmatic inquiry 3. Pretext concerns of special needs searches A. Must be programmatic (not general crime fighting) (use Brown balancing test) B. Must be standardized (like inventory searches) 4. Other special needs searches A. School searches 1. New Jersey v. T.L.O. (1985) A. If reasonable suspicion (by principal), can search lockers, containers 1. No warrant required; no p/c B. State interest in proving safe public school environment (diminished expectation of privacy at school) 2. Random drug testing at schools A. Vernonia School District v. Acton (1995) 1. Random testing of students involved in sports constitutional (no need for individualized r/s to begin such program -- de minimis intrusion) 2. The Earls case (2002) A. Random testing of all students in extra-curricular activities constitutional B. At workplace 1. Skinner v. Railway Labor Executives’ Association (1989) A. Constitutional to do random blood and urine tests of certain employees (eg, engineers) B. Special needs: Safety 2. National Treasury Employees Union v. Von Raab (1989) A. Constitutional to do random tests of customs employees B. Special needs: drug control C. Candidates for public office 1. Chandler v. Miller (1997) A. Unconstitutional for Georgia to do random drug testing for candidates of public office B. No special needs Q. Force in making seizure (when reasonable) 1. Tennessee v. Garner (1985) A. Two-part test for when to use deadly force in making arrest 1. Have probable cause D poses significant threat of death or serious physical injury 2. Officer must reasonably believe deadly force is necessary to make arrest or D will escape B. “It is not better that all felony suspects die than that they escape.” 2. Graham v. Conner (1989) A. Fourth Amendment reasonableness standard governs all use of force by police B. Excessive force -- Totality of circumstances test to determine if excessive force is used 1. Look to whether D has weapon 2. Degree of danger posed 3. Seriousness of crime R. “Standing” 1. Court uses “personal privacy” (“personal rights”) approach to determine if D can contest wrongful search / seizure -- eliminates “standing” analysis A. Rakas v. Illinois (1978) 1. Test for “standing” -- Does D have a reasonable expectation of privacy in area searched? 2. Here, D, a passenger in car, did NOT have reasonable expectation of privacy in glove box or under seat B. Minnesota v. Olson (1990) 1. Overnnight guest has a reasonable expectation of privacy to contest search C. Rawlings v. Kentucky (1980) 1. Ownership of property seized as a result of a search does not by itself entitle an individual to challenge the search 2. Here, D didn’t own purse, but drugs inside -- D didn’t have REP in purse D. Minnesota v. Carter (1998) 1. Ds in apartment to bag cocaine did NOT have reasonable expectation of privacy 2. More of a commercial transaction at the apartment -- not like overnnight social guest 2. Remember: ask (1) is there a reasonable expectation of privacy, and (2) is there a constitutional violation of privacy IV. Exclusionary Rule - Fruit of the poisonous tree A. Generally 1. Primary evidence A. Evidence immediately from constitutional violation 2. Derivative evidence (the “fruit”) A. Evidence found that flows from primary evidence found b/c of constitutional violation 3. Policy to exclude A. Deter police from constitutional violations 1. Contrast -- b/c constable blunders, criminal goes free B. Put gov’t in position as if violation hadn’t occurred (NB, not a worse position) 4. CAUSATION analysis A. “but for” cause 1. Independent source 2. Inevitable discovery B. Proximate cause 1. Attenuation of the taint B. Independent Source Doctrine 1. Evidence is admissible, despite police illegality, if the evidence seized is not causally linked to the wrongdoing 2. Murray v. United States (1988) A. HOLD: Although police illegally entered warehouse and found marijuana, a second warrant-based search that would have occurred even without illegal entry means there was an independent source for finding the drugs--making drugs admissible B. Policy 1. Would have found drugs anyway 2. Won’t risk “confirmatory” searches C. Inevitable Discovery Doctrine (hypothetical independent source) 1. Nix v. Williams (1984) A. Evidence relating to murder victim’s body admissible, notwithstanding the Sixth Amendment violation during car ride, b/c body would have been found ultimately anyway B. Burden to prove inevitable discovery -- preponderance 1. Dissent wants a “clear and convincing” standard C. No “good faith” analysis 2. Circuit Courts of Appeal have placed various limits on inevitable discovery (not yet ruled on by Supreme Court) A. Apply only to derivative evidence (won’t allow for primary evidence) B. Police must be in active pursuit of warrant (getting warrant during illegal search) D. Attenuation of taint 1. Do a proximate cause analysis (a totality of the circumstance) to determine if taint has dissipated and evidence admissible A. FACTORS (look to break chain from violation to evidence) 1. Temporal proximity 2. Spacial proximity 3. Remoteness in chain of events 4. Voluntariness (free will) 5. Type of evidence (live witness or inanimate) (notes, nature of evidence, infra) 6. Flagrancy of violation A. CONCUR (Powell) -- wants to distinguish between “flagrant” violation and “technical” violation 2. Wong Sun v. United States (1963) A. Established rule: has evidence been found by exploitation of illegality or instead by means sufficiently distinguishable to be purged of primary taint B. D returning to police station and providing written statement is voluntary enough to remove taint 3. Brown v. Illinois (1975) A. “Miranda warnings, alone and per se, cannot always make the act sufficiently a product of free will to break, for Fourth Amendment purposes, the causal connection between the illegality and the confession.” B. Man illegally arrested and read Miranda rights can have confession suppressed. No remoteness of events, Miranda didn’t break chain (only one factor of several, see notes, supra) 4. Nature of the evidence A. United States v. Ceccolini (1978) 1. HOLD: Cop, who illegally opens envelope, gets statements from witness; witness statements sufficiently attenuated for admission A. Distinction between live witnesses and inanimate objects B. Live people may come forward (taint diminishes faster) 2. Dissent -- Double-counting (both inevitable discovery and attenuation) B. New York v. Harris (1990) 1. HOLD: D, arrested illegally in house, makes statement outside of house; statement admissible b/c violation was illegal entry in home; continuing custody is not a continuing constituional violation 2. Payton rule designed to protect integrity of home and doesn’t protect statements made outside of home E. Impeachment Exception 1. Can use illegally seized evidence to impeach witness who testifies contrary to evidence F. “Good faith” exception 1. Not an exception to Fourth Amendment, but exception to Exclusionary Rule 2. United States v. Leon (1984) A. Evidence obtained pursuant to search warrant later determined to be invalid may be introduced in prosecution’s case-in-chief if a reasonably well-trained officer would have believed warrant was valid B. Exceptions to Leon (objective test: reasonable officer) 1. Magistrate relied on information from affiant who purposefully lied 2. Magistrate so lacking in neutrality a reasonable officer would know magistrate is not acting impartially 3. Officer may not rely on warrant so lacking in indicia of probable cause as to render any belief in p/c entirely unreasonable 4. Officer may not rely on warrant so facially deficient--not specifying place, things to be seized--that it’s unreasonable to presume it’s valid C. Policy 1. No deterrence of officers who reasonably--in “good faith”--believe warrant is valid 2. No need to try to deter magistrates, who won’t want to be overruled on p/c anyway A. DISSENT -- If would exclude, then deter magistrate shopping and make officers more careful (investigate more rather than hope magistrate will “take the bait” of a suspect warrant); need to retain exclusionary rule D. Extending Leon 1. Arizona v. Evans (1995) A. Court clerk mistake that said warrant for D (when warrant was supposed to quashed) that led to officer searching incident to arrest and finding drugs; drugs admissible (officer reasonably relied, even though court mistake) 2. Illinois v. Krull (1987) (Nowlin provided no further info.) A. Extends Leon logic to Legislature; if statute later invalid, still evidence can be admitted as long as officer acted reasonably in relying on it before it’s invalidated G. Scope of Exclusionary Rule 1. Only applies to criminal trial (not to civil cases) 2. Only applies to prosecution’s case-in-chief 3. Does not apply to preliminary hearing, bail hearing, sentencing or parole V. Interrogation Law A. Generally 1. Confessions A. Efficient B. Good evidence C. Scalia’s “good for the soul” 2. Interrogation A. Concerns 1. Rights of individual as relate to coercion A. Human rights 2. Reliability (false confessions) 3. Maintaining integrity of trial process 3. Three overall bodies of law A. Voluntariness (the DPC test) 1. Applies to Fifth (self-incrimination) / Fourteenth Amendment (due process) B. Miranda Warnings 1. Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination C. Sixth Amendment right to counsel B. Voluntariness (the DPC test) 1. Fifth Amendment and 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause prohibits admissibility of involuntary confessions A. Bram v. United States (1897) 1. HOLD: For federal cases, through Fifth Amendment right against self incrimination, confession must be free and voluntary; not extracted A. Brown v. Mississippi (1936) 1. Ds, tortured by sheriff, did not voluntarily confess to murder 2. Fourteenth Amendment DPC invoked to invalidate convictions at state level 2. Ashcraft v. Tennessee (1944) A. HOLD: Thirty-six hour interrogation is too long to get voluntary confession from D 3. Spano v. New York (1959) A. HOLD: D did NOT voluntary confess after eight-straight hour interrogation, having asked for his lawyer, and after friend (a cop) was used to help get confession -overborne with official pressure and fatigue 4. Prohibitions and concerns under DPC test A. Force (can’t) B. Threat of force (can’t) C. Psychological interrogation (good cop/bad cop, at some point too much) D. Promises of leniency (goes into mix, but not forbidden) E. Promises of harsh punishment (goes into mix, but not forbidden) F. Lie about legal implications (can‘t) G. CAN lie about facts 5. Colorado v. Connelly (1986) A. Have to have police overreaching to find an involuntary confession 7 Other issues A. Exclusionary rule 1. Have right to exclusion (this is the violated right stemming from DPC violation) B. “Standing” is required C. No ‘good faith’ exception D. No ‘impeachment’ exception E. Make a 1983 claim -- “shocks the conscience” test PROTECTIONS MIRANDA DPC / VOLUNTARINESS C. Miranda v. Arizona (1966) 1. “(T)he prosecution may not use statements, whether exculpatory or inculpatory, stemming from custodial interrogation of the D unless it demonstrates the use of procedural safeguards effective to secure the privilege against self-incrimination.” A. POLICY 1. To dispel coercive atmosphere from interrogation in custody 2. Totality of circumstances test was not working to dispel coercive atmosphere A. Miranda is prophylactic rule to protect beyond totality of circumstances test Full custody + Interrogation = Coercive atmosphere Coercive atmosphere -- dispelled by Miranda warnings B. Safeguards 1. Tell D rights: A. Remain silent 1. D is in control 2. Silence is not viewed as implicit admission of guilt B. Any said USE against D 1. This is an adversarial process C. Attorney 1. If need help, can receive D. Appoint attorney if can’t afford 2. CUSTODY -- Must be full custody for Miranda to kick in A. Berkemer v. McCarty (1984) 1. Officer who had subjectively decided he would arrest D, but hadn’t yet done it, was free to ask D questions and D respond without giving Miranda because D was not yet under formal arrest 2. TEST: Would a reasonable person believe he is under the functional equivalent of a formal arrest? 3. INTERROGATION A. Rhode Island v. Innis (1980) 1. “A practice that the police should know is reasonably likely to evoke an incriminating response from a suspect thus amounts to an interrogation…the definition of interrogation can extend only to words or actions on the part of police officers that they should have known were reasonably likely to elicit an incriminating response.” 2. Must be a direct /express question or functional equivalent of question A. DISSENT: Allows police to take long-shots at interrogating Ds B. DISSENT: Want test to be would reasonable person believe it would elicit a response B. Illinois v. Perkins (1990) 1. Miranda warnings are not required when D is unaware he is speaking to a law enforcement officer and gives a voluntary statement. 2. Here, inmate to inmate (undercover agent) in prison cell (not coercive, though D is in full custodial arrest) 3. NB Still have Voluntariness/DPC test, even if no need for Miranda A. Arizona v. Fulminante (1991) 1. Suspected child killer, in jail, was offered “protection” from other inmates by undercover cop if D confessed to crime. D confessed, but court held it was not voluntarily given 4. Waiver of Miranda A. Defining waiver 1. Johnson v. Zerbst (1938) A. Constitutional right can only be waived if “voluntary,” “knowingly” and “intelligently” B. A totality of the circumstances test B. Waiver can be 1. Express or implied A. Mere silence in face of warnings can not be waiver B. But if D says, “I’ll talk with you.” -- implied wavier 2. Oral or written C. Reinitiation 1. Oregon v. Bradshaw (1983) A. If D initiates further communication with police, then validly waived rights under Miranda (nb -- still need Zerbst) 1. Here, D said “Well, what’s going to happen to me now?” 2. Waived invocation of Edward’s rule (plurality holding) B. Initiation -- willingness, desire to talk about general investigation 5. Invoking Right to Silence A. Michigan v. Mosley (1975) 1. Police must “scrupulously honor” a D’s invocation of right to silence A. Doesn’t mean police can’t come back and try to ask D questions again as long as “scrupulously honor” first request, and then obtain a valid Zerbst waiver 2. POLICY A. Don’t want badgering by police of D B. DISSENT: Wants attorney present before police come back C. CONCUR: Just stick with Zerbst test; no more needed B. NB: D can ALWAYS reinitiate communication with police, so no need for “scrupulously honor” then, though police would need a Zerbst waiver 6. Invoking Right to Attorney A. Edwards v. Arizona (1981) 1. Once D invokes right to attorney, there can be no more interrogation until counsel is made available A. EXCEPTION -- If D reinitiates communication with police / gives Zerbst waiver 2. POLICY A. It’s a “cry for help” -- D may be intimidated by atmosphere B. Offers second layer of protection to Miranda B. Davis v. United States (1994) 1. D must unambiguously request counsel, sufficiently clear that a reasonable police officer in the circumstances would understand the statement to be a request for an attorney 2. If D’s statement is not unambiguous, police have NO obligation to stop questioning him, or clarify 3. Policy debate: A. D may feel threatened by police and want attorney -- should clarify 1. Souter’s position B. D should be able to articulate wants attorney -- no need to clarify 1. Coercive atmosphere should already be dispelled with Miranda 2. O’Connor for majority here C. Can’t treat ambiguous request as full invocation 1. May trap in own rights 2. Obstacle to law enforcement 4. Smith v. Illinois (1984) A. “(A)n accused’s post-request responses to further interrogation may not be used to cast retrospective doubt on the clarity of the initial request itself.” C. Minnick v. Mississippi (1990) 1. Once right to counsel invoked, police may not reinitiate interrogation with D without counsel present, regardless of whether D has met with counsel 7. Public safety exception to Miranda A. New York v. Quarles (1984) 1. In exigency situation, where officer is reasonably prompted by a concern for the public safety, can ask D questions before reading Miranda warnings A. Here, D had hidden gun in a carton in a store 2. A totality of the circumstances (inkblot) test 3. Policy A. Public safety outweighs need for prophylactic rule B. NB Could still violate DPC/Voluntariness test (“shocks the conscience”) 8. General issues A. Constitutional violation 1. The admission of evidence illegally obtained A. Contrast with Fourth Amendment B. Fruit of the poisonous tree 1. Little to none 2. Michigan v. Tucker (1974) A. Police obtained statement in violation of Miranda which led to witness. Witness can be admitted at trial 3. Oregon v. Elstad (1985) A. Police obtained first statement from D in violation of Miranda. Then, second statement given after Miranda warnings, was challenged as fruit from the first. Court held second statement could be used. C. Impeachment exception 1. Can use wrongfully obtained statement to impeach D A. NB DPC/Voluntariness does NOT have impeachment exception D. Constitutional status of Miranda 1. Called a “constitutional rule” in Dickerson v. United States (2000) A. Unclear what that means VI. Sixth Amendment A. Generally 1. Policy A. Need legal expert to provide D with guidance through the legal system B. Advocate for D (adversarial system wouldn’t work without it) C. Extend to pretrial interrogation because: 1. Need buffer between state and D 2. Pre-trial statements are as important as trial statements (right to counsel is no good if attorney can’t help prior to trial) B. Massiah v. United States (1964) 1. BRIGHT-LINE -- Once formal judicial proceedings begun, right to counsel attaches 2. Here, use of undercover agent to gather information from D--outside of police custody and after formal proceedings--is a violation of the Sixth Amendment r/c A. “Any secret interrogation of the D, from and after the finding of the indictment, without the protection afforded by the presence of counsel, contravenes the basic dictates of fairness in the conduct of criminal causes and the fundamental rights of persons charged with crime.” (quoting People v. Waterman) C. Brewer v. Williams (1977) 1. HOLD: “Christian burial speech” is an attempt at deliberate elicitation from D and is a violation of Sixth Amendment right to counsel. 2. Police can’t try to deliberately elicit information once Sixth Amendment’s right to counsel asserted A. A subjective test B. DEFINING deliberate elicitation 1. DELIBERATE (essentially, mental state) A. subjective intent B. Purpose, knowingly, reckless 2. ELICITATION (essentially, actus reus) A. Kulhmann v. Wilson (1986) 1. Police must do something beyond passive listening to be trying to elicit A. Try to stimulate conversation related to offense 2. Hear spontaneous, unsolicited remarks permissible 3. In Kulhmann, police allowed to put agent in jail cell with person against whom formal charges had been brought as long as there were no investigatory techniques that are equivalent of interrogation D. Patterson v. Illinois (1988) 1. “(A)s a general matter, (an) accused who is (given Miranda warnings) has been sufficiently apprised of the nature of the Sixth Amendment rights, and of the consequences of abandoning those rights, so that his waiver on this basis will be considered a knowing and intelligent one.” 2. Waiver of Miranda rights can also be waiver of Sixth Amendment if know have been indicted E. Michigan v. Jackson (1986) 1. An Edwards-rule for the Sixth Amendment 2. Once D invokes right to counsel under Sixth Amendment, police can’t initiate interrogation without counsel present and there can be no waiver of the right to counsel without D’s attorney there F. Sixth Amendment if OFFENSE SPECIFIC 1. McNeil v. Wisconsin (1991) A. An invocation of the Sixth Amendment right to counsel at a bail hearing is NOT an invocation for Miranda right to counsel for future police questioning about crimes D is not formally charged with Contrasts between Miranda rights and Sixth Amendment’s right to counsel Fifth Amendment Sixth Amendment Requires full custody Protects even when not in custody Not offense specific Offense specific 2. How apply offense-specific A. Blockburger v. United States (1932) 1. Two distinct statutory provisions constitute separate offenses if “each provision requires proof of a fact which the other does not.” A. Crime 1: prove A, B and C B. Crime 2: prove A, B and D C. TWO SEPARATE OFFENSES 2. An elemental analysis A. Lesser, included offenses are part of the same offense G. Other issues 1. Right under Sixth Amendment is right to exclude evidence 2. Probable impeachment exception 3. Full fruit of the poisonous tree under Sixth Amendment