Florida v. Jardines and Canine sniffs of the Home

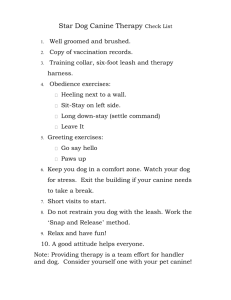

advertisement

LEGAL UPDATE “Hound Dogs, Seizures, DNA and Blood” or “Saturday Night in Muhlenburg County” A Good Year! For the Florida Folks Road Map • Florida v. Clayton Harris • Florida v. Jardines • Maryland v. King • Bailey v. US • Missouri v. Mcneely FLORIDA V. CLAYTON HARRIS: “Canine Searches on “Rocky Ground?” Canine Units • Hard to get national numbers • Larger organizations have multiple units • Not cheap ($19-20k) initial investment • On going costs • Private vendors • Self established criteria • Profit 4th Amendment • The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the person or things to be seized. Reasonable Expectation of Privacy • Katz v. U.S. (1967) • Appeared to cast off the yolk of property law as the basis of Fourth Amendment analysis and adopted a privacy approach. • “Fourth Amendment protects people, not places … What a person knowingly exposes to the public, even in his own home or office, is not a subject of Fourth Amendment protection … but what he seeks to preserve as private, even in an area accessible to the public, may be constitutionally protected” (Justice Harlan’s concurrence in Katz v. U.S.1967: 351-352). Test for REP • 1. The person must first have shown an actual subjective expectation of privacy in a matter. • 2. The subjective expectation of privacy manifested by the person must be of such a nature that society is willing to recognize it as reasonable; • Both gets you REP • REP gets you standing to object to the search or seizure Seminal Canine Sniff Case Law • US v Place (1983) • Seizure of luggage based on RS and subjected to a canine sniffOK. • City of Indianapolis v. Edmond (2000) • Car at checkpoint subject to canine sniff- Sniff OK. • Illinois v. Caballes (2005) • Car at lawful traffic stop subject to canine sniff-OK. Why are canine sniffs different? • Canine sniff “sui generis” • Minimally Intrusive. • No rummaging through your stuff • Only detects the presence of contraband • Nothing revealed but the bad stuff Reliability • The Fourth Amendment presumptively requires a warrant for all searches or seizures. • Narrowly tailored exceptions have been created to allow state actors to search without warrants but based upon probable cause. • Trained drug detection alerts are one such exception. • This exception flows from the perceived reliability of canine sniffs to detect contraband and thus supply probable cause for the belief contraband is present. • The canine’s reliability is the foundation of the warrantless search behavior. Relaiable Canine Snif Alert Proable Cause Warrantless Search Establishing Legal Reliability • The method, manner, and evidence used to prove a canine’s reliability has received considerable attention in the courts. • Federal courts generally certification is enough. • Types of evidence: • Certification (for both dog and handler) • Training records (for both dog and handler) • Training descriptions (for both dog and handler) • Re-certifications (for both dog and handler) • Field Performance Records Field Reliability • Legal reliability is different from actual/factual reliability. • Legal reliability supports the states’ action. • Factual reliability goes to the actual presence of contraband. • The potential for residual contraband clouds the issue. • Recently removed or very tiny amount Canine Alert Reliable Potentially Unreliable Alert Contraband Present Alert Contraband Not Present Potential False Positive Residual Contraband Present *“Field/Practical” False Positive* No Residual Contraband Present “True” False Positive (Over alert) No Canine Alert No Alert and Drugs NOT Present No Alert and Drugs Present False Negative (Under alert) Florida v. Clayton Harris • Harris was initially stopped for an expired license plate. • Officer Wheetley observed that Harris was very nervous with shaking hands and rapid breathing. • Wheetley ask for consent to search the vehicle but Harris declined. • Officer Wheetley then retrieved Aldo and walked him around the car. The dog alerted on the driver’s side door handle. • Officer Wheetley, based on the alert, searched the vehicle and found “200 loose pseudoephedrine pills, 8,000 matches, a bottle of hydrochloric acid, two containers of antifreeze, and a coffee filter of iodine crystals” but no drugs. Facts • After being Mirandized Harris admitted to abusing and cooking methamphetamine. • He was charged with possession of precursors for use in the production of methamphetamine. • Harris was stopped subsequently while on bail again by Officer Wheetley and Aldo for a broken tail light. Aldo sniffed the exterior of the car and altered again upon the driver’s side door handle. • No contraband was found in the search that followed. Facts 3 • Harris moved to suppress the evidence asserting that the alert by Aldo did not amount to probable cause. • Wheetley testified about the training that both he and Aldo had received. • Wheetley was trained with a different dog and Aldo with a different handler. • Aldo was also certified by a private company for a year. • Together Wheetley and Aldo participated in a 40 hour refresher course and conducted 4 hours a week of continued training. • Wheetley admitted on cross examination that he did not keep full field performance records for Aldo, rather he only recorded alerts that culminating in arrests. Facts 4 • Motion fails. • Florida Supreme Court overturns. • “Evidence that the dog has been trained and certified to detect narcotics, standing alone, is not sufficient to establish the dog’s reliability for purposes of determining probable cause- especially since training and certification in this state are not standardized and thus each training and certification program may differ with no meaningful way to assess them” (759). • To “establish a reasonable basis for believing the dog to be reliable” the state “must present the training and certification records, an explanation of the meaning of the particular training and certification for that dog, field performance records, and evidence concerning the experienced training of the officer handling the dog, as well as any other objective evidence known to the officer about the dog’s reliability in being able to detect the presence of illegal substances within the vehicle” (759). Issue • The issue reviewed by the Court focused on Florida’s mandatory evidentiary requirements language. • Whether the requirement that “the state must in every case present an exhaustive set of records, including a log of the dog’s performance in the field, to establish the dog’s reliability” is proper? Holding • The required evidence of the canine’s performance was “inconsistent with the flexible, common-sense standard of probable cause”. • Reliability examination should unfold as follows: “if the State has produced proof from controlled settings that a dog performs reliably in detecting drugs, and the defendant has not contested that showing, then the court should find probable cause. If, in contrast, the defendant has challenged the State’s case (by disputing the reliability of the dog overall or of a particular alert), then the court should weigh the competing evidence. Holding 2 • In all events, the court should not prescribe, as the Florida Supreme Court did, an inflexible set of evidentiary requirements. • The question—similar to every inquiry into probable cause—is whether all the facts surrounding a dog’s alert, viewed through the lens of common sense, would make a reasonably prudent person think that a search would reveal contraband or evidence of a crime.” Reasoning • Difficult concept--probable cause is better thought of as a “fair probability” on which reasonable and prudent [people,] not legal technicians act” • The test for probable cause looks to the totality of the circumstances. • fluid and rejects “rigid rules, bright line tests”. • Florida requirements directly conflict with the protean legal nature of probable cause. Reasoning • The weaknesses of field performance evidence. • Asserting that in such records false negatives would never be known as no search is conducted when the dog does not alert but drugs are present • and that in false positive situations where the dog alerts and drugs are not found may be the result of residual odors or drugs that are too well hidden to be found by the officer. Reasoning • Better evidence of a dog’s reliability comes from controlled testing environments like training and certification programs Two rules regarding reliability • First, “if a bona fide organization has certified a dog after testing his reliability in a controlled setting, a court can presume (subject to any conflicting evidence offered) that the dog’s alert provides probable cause to search”. • Second, a court may also presume that a dog’s alert provides probable cause “even in the absence of formal certification, if the dog has recently and successfully completed a training program that evaluated his proficiency in locating drugs”. Discussion • Wide variation in training and certification of canines will • • • • continue. Performance/field records potentially used but not likely. Difficulty in establishing a dogs reliability if you are a defendant. Unknown impact of handlers on canine behaviors on the street. Might some officers be motivated by things other than the desire to find “contraband without incurring unnecessary risks or wasting limited time and resources” ? Vote Constitutional • Kagan • Ginsburg • Breyer • Sotomayor • Scalia • Kennedy • Roberts • Alito • Thomas 9-0 FLORIDA V. JARDINES AND CANINE SNIFFS OF THE HOME: “Frank[y] I don't know what I'm gonna find” Grow Houses • Appear to be increasing • Quality product demands high price • Improvement in hydroponics • Housing bubble? • Dangerous-fire/explosion. • Crime generator? Grow Houses • Appear to be increasing • Quality product demands high price • Improvement in hydroponics • Housing bubble? • Dangerous-fire/explosion. • Crime generator? 4th Amendment • Katz and REP • Test for REP • Subjective • Objective • Same Canine Sniff case law and rationale for why canine sniffs are different from other searches. Home Sweet Home! Kyllo v. U.S. • “Whether the use of a thermal-imaging device aimed at a private home from a public street to detect relative amounts of heat within a home constitutes a ‘search’ within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment” (Kyllo v. U.S. 2001:4432)? • The opinion held: “where … the Government uses a device that is not in general public use, to explore details of the home that would previously have been unknowable without physical intrusion, the surveillance is a ‘search’ and is presumptively unreasonable without a warrant” (Kyllo v. U.S. 2001:4435). US v Jones (2012) • Issue: • Whether the attachment of a Global-Positioning-System (GPS) tracking device to an individual’s vehicle, and subsequent use of that device to monitor the vehicle’s movements on public streets, constitutes a search or seizure within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment. • Holding: • The Government’s attachment of the GPS device to the vehicle, and its use of that device to monitor the vehicle’s movements, constitutes a search under the Fourth Amendment. US v. Jones • Reasoning: • Katz did not repudiate the understanding that the Fourth Amendment embodies a particular concern for government trespass upon the areas it enumerates. The Katz reasonableexpectation-of-privacy test has been added to, but not substituted for, the common-law trespassory test. Florida v. Jardines • Drug investigation--Miami-Dade Police Department. • Detective Pedraja received an unverified tip that Jardines was • • • • • growing marijuana in his home. Detective along with Detective Bartlet and a drug detection dog-Franky went to the Jardines home. Franky walked toward the home and near the front of the home the dog alerted. The detective then went to the front door of the home and smelled marijuana. He also observed that the air conditioning had run constantly for approximately 15 minutes. The detective used his observations as well as the canine alert in an affidavit in support of a search warrant. A warrant was issued and executed. The search found a grow operation in the home and Jardines was arrested. Issue • Whether using a drug-sniffing dog on a homeowner’s porch to investigate the contents of the home is a “search” within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment? Holding • The Government’s use of trained police dogs to investigate the home and its immediate surroundings is a “search” within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment. Reasoning • The Fourth Amendment context a person’s home is “is first among equals” and that the idea that a person may “retreat into his own home and there be free from unreasonable governmental intrusion” sits at the “core” of the amendment. • The space ““immediately surrounding and associated with the home” --what our cases call the curtilage--as “part of the home itself for Fourth Amendment purposes.” Reasoning-Knock and Talk • The critical question in this determination focused upon whether intrusion on the porch “was accomplished through an unlicensed physical intrusion”. • The law may infer a license based upon custom. Justice Scalia noted that an “implicit license typically permits the visitor to approach the home by the front path, knock promptly, wait briefly to be received, and then (absent invitation to linger longer) leave” and that “a police officer not armed with a warrant may approach a home and knock, precisely because that is “no more than any private citizen might do.” Reasoning-why your here • The opinion noted that there is no customary invitation to bring a trained police dog to sniff the curtaliage in an attempt to discover evidence of criminality. In short, “the scope of a license--express or implied--is limited not only to a particular area but also to a specific purpose”. Reasoning and REP • The opinion then dealt with the potential for a canine sniff to trigger a reasonable expectation of privacy. Here the Justice noted that Jones established that “the Katz reasonable-expectations test “has been added to, not substituted for,” the traditional property-based understanding of the Fourth Amendment, and so is unnecessary to consider when the government gains evidence by physically intruding on constitutionally protected areas. Vote Unconstitutional Constitutional • Kagan • Roberts • Ginsburg • Alito • Sotomayor • Kennedy • Scalia • Breyer • Thomas MARYLAND V. KING DNA and not for Maury Povich Facts • In 2003 a man concealing his face and armed with a gun broke into a woman’s home in Salisbury, Maryland. He raped her. The police were unable to identify or apprehend the assailant … but they did obtain from the victim a sample of the perpetrator’s DNA. • In 2009 Alonzo King was arrested …and charged with first- and second-degree assault for menacing a group of people with a shotgun. As part of a routine booking procedure for serious offenses, his DNA sample was taken…. The DNA was found to match the DNA taken from the Salisbury rape victim. King was tried and convicted for the rape. Law’s Limitations • LEOs can collect DNA samples from “an individual who is charged with . . . a crime of violence or an attempt to commit a crime of violence; or . . . burglary or an attempt to commit burglary.” • crime of violence = murder, rape, first-degree assault, kidnaping, arson, sexual assault, and a variety of other serious crimes. • Once taken, a DNA sample may not be processed or placed in a database before the individual is arraigned (unless the individual consents) • a judicial officer ensures that there is probable cause to detain the arrestee on a qualifying serious offense. Law’s Limitations • If “all qualifying criminal charges are determined to be unsupported by probable cause . . . the DNA sample shall be immediately destroyed.” • DNA samples are also destroyed if “a criminal action begun against the individual . . . does not result in a conviction,” “the conviction is finally reversed or vacated and no new trial is permitted,” or “the individual is granted an unconditional pardon • Tests for familial matches are also prohibited. • No purpose other than identification is permissible. Issue • May the police collect DNA from a person arrested for a serious crime without a warrant? Holding • Yes, DNA identification of arrestees is a reasonable search that can be considered part of a routine booking procedure. • When officers make an arrest supported by probable cause to hold for a serious offense and they bring the suspect to the station to be detained in custody, taking and analyzing a cheek swab of the arrestee’s DNA is, like fingerprinting and photographing, a legitimate police booking procedure that is reasonable under the Fourth Amendment. Reasoning • The Fourth does apply to this process. • Usually, we have some quantum of individualized suspicion to have a constitutional search but not always. • In the Special Needs cases the critical determination is that of “reasonableness”. • That is, they must be reasonable in scope and manner of execution. Reasoning • To determine reasonableness the Court must balance the promotion of a legitimate government interest against the degree to which the search intrudes on an individual’s privacy. • Here the legitimate government interest is to identify persons taken into custody. It allows police to search records already in their possession to understand the person arrested. This can enhance the safety of staff and others in detention. It can inform bail decisions. • The intrusion is small-a swab of the inside of the mouth. The search is incident to arrest. There is no threat to the safety of the person searched. Nor does the search add much to indignity associated with arrest. BAILEY V. US My house if a mile away? Facts • Police get a warrant to search a residence. Officers doing prewarrant surveillance see two men leave and get into a car. Both men match description of person thought to be in the residence. The officers follow the men while search team executes the warrant. The officers pull over the car after following for about five minutes, a mile or so away from residence. Facts • Ordered out of car and patted down. The two men were placed in handcuffs. They asked why they were being detained and were told it was because of the execution of the warrant. Search team finds gun and drugs. Issue • Whether the seizure of the person is reasonable when he was stopped and detained at some distance away from the premises to be searched when the only justification for the detention was to ensure the safety and efficacy of the search? Holding • This seizure was unreasonable. Once an individual has left the immediate vicinity of a premises to be searched, however, detentions must be justified by some other rationale. Reasoning • Summers case-detention is allowed without probable cause to arrest for a crime. It permitted officers executing a search warrant “to detain the occupants of the premises while a proper search is conducted.” • No particularized suspicion or danger to officers-just being there allows this practice. Reasoning • Summers had three core reasons: • “the interest in minimizing the risk of harm to the officers” • “the orderly completion of the search may be facilitated if the occupants of the premises are present.” • “the legitimate law enforcement interest in preventing flight in the event that incriminating evidence is found.” Reasoning • None of those really work well with the facts of the case. • Allowing this would give too much discretion. These detentions did not happen in the home so more inconvenience and indignity. • Limiting the rule in Summers to the area in which an occupant poses a real threat to the safe and efficient execution of a search warrant ensures that the scope of the detention incident to a search is confined to its underlying justification Reasoning • In closer cases courts can consider a number of factors to determine whether an occupant was detained within the immediate vicinity of the premises to be searched, including the lawful limits of the premises, whether the occupant was within the line of sight of his dwelling, the ease of reentry from the occupant's location, and other relevant factors. MISSOURI V. MCNEELY I’ve come for your blood Facts • McNeely stopped for speeding and crossing center line. Officer notices bloodshot eyes, slurred speech, and the smell of alcohol on his breath. He performed poorly on a battery of field-sobriety tests and declined to use a portable breath-test device. Facts • During transport McNeely indicated that he would again refuse to provide a breath sample, the officer then took McNeely to a nearby hospital for blood testing. • The officer did not attempt to secure a warrant. • Upon arrival at the hospital, the officer asked McNeely whether he would consent to a blood test. The officer explained to McNeely that under state law refusal to submit voluntarily to the test would lead to the immediate revocation of his driver’s license for one year and could be used against him in a future prosecution. McNeely nonetheless refused. • The officer then directed a hospital lab technician to take a blood sample. Issue • Whether the natural metabolization of alcohol in the bloodstream presents a per se exigency that justifies an exception to the Fourth Amendment’s warrant requirement for nonconsensual blood testing in all drunk-driving cases? Holding • We conclude that it does not, and we hold, consistent with general Fourth Amendment principles, that exigency in this context must be determined case by case based on the totality of the circumstances. • We hold that in drunk-driving investigations, the natural dissipation of alcohol in the bloodstream does not constitute an exigency in every case sufficient to justify conducting a blood test without a warrant. Reasoning • Generally a warrantless search of the person is reasonable only if it falls within a recognized exception. The seizure here implicates an individual’s “most personal and deep-rooted expectations of privacy”. Yet the Court has recognized that in some circumstances law enforcement officers may conduct a search without a warrant to prevent the imminent destruction of evidence. Reasoning • To determine whether a law enforcement officer faced an emergency that justified acting without a warrant, this Court looks to the totality of circumstances. Yes, the body does metabolize evidence but that is not enough to force the law to abandon the TOC test. There is always some delay associated with transport for testing. Officers could start the warrant process while another officer transported the suspect. Reasoning • A per se exception also ignores the advances in obtaining warrants remotely. Examples, telephonic or radio communication, electronic communication such as e-mail, and video conferencing. Jurisdictions have also streamlined the warrant process, such as by using standard-form warrant applications. Reasoning • The Court is not going to give a list of factors but the opinion noted that the metabolization of alcohol in the bloodstream and the ensuing loss of evidence are among the factors that must be considered in deciding whether a warrant is required. • No doubt, given the large number of arrests for this offense in different jurisdictions nationwide, cases will arise when anticipated delays in obtaining a warrant will justify a blood test without judicial authorization…. Questions • Thank you