Drinking Water in Virginia

advertisement

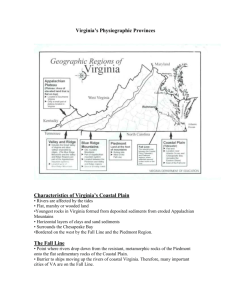

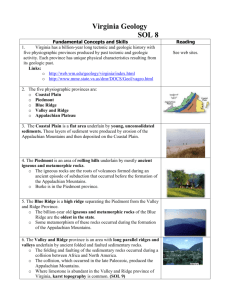

What’s in Your Water? Drinking Water in Virginia Erin Ling, M.S. Virginia Tech Biological Systems Engineering Virginia Cooperative Extension Where does your water come from? Public or private supply? Bottled? Groundwater? Surface water? Both? Who manages your water system and water quality? Is there a source water protection plan in place for your water supply? What do you know about your water quality? 2 Today’s Presentation • The water cycle and groundwater in Virginia • Public vs. Private Water Supplies • Drinking Water Regulations • Care and maintenance of private water systems • Well location, protection, and construction • Well maintenance and care • Water testing • Dealing with water problems • Virginia Household Water Quality Program • Virginia Master Well Owner Network 3 The Water Cycle Ground-Water-Flow System (Natural Conditions) Direction and Rate of Ground-Water Movement Aquifer Material Sand Shell material Crystalline rock Sedimentary rock Carbonates Coal Physiographic Provinces of Virginia Coastal Plain Coastal Plain Piedmont Piedmont Mesozoic Lowlands Mesozoic Lowlands Blue Ridge BlueValley Ridge and Ridge Valley and Ridge Appalachian Plateau Appalachian Plateau Hydrogeology of the Appalachian Plateau SPRING FRACTURES NOT TO SCALE Geology Generalized Ground-Water Flow Path Colluvium and Alluvium Sandstone Weathered Bedrock Coal Seam Geology NOT TO SCALE Geology Generalized Ground-Water Flow Path Colluvium and Alluvium Modified from Harlow and LeCain, 1991 m and Alluvium Weathered Bedrock ed Bedrock e or Shale nd LeCain, 1991 Sandstone Coal Seam Siltstone or Shale Modified from Harlow and LeCain, 1991 Older Ground Water Coastal Plain Piedmont Mixture of Younger and Older Lowlands Ground Water Mesozoic Generalized Ground-Water Flow Path NOT TO SCALE Siltstone or Shale Younger Ground Water Sandstone Younger Ground Water Coal OlderSeam Ground Water Mixture of Younger and Older Ground Water Blue Ridge Valley and Ridge Younger Ground Water Plateau Appalachian Older Ground Water Mixture of Younger and Older Ground Water Hydrogeology of the Valley and Ridge West East ? Coastal Plain Piedmont Mesozoic Lowlands Blue Ridge Valley and Ridge Appalachian Plateau From: Harlow, G.E., Jr., Orndorff, R.C., Nelms, D.L., Weary, D.J., and Moberg, R.M., U. S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2005-5161, p. 30. Hydrogeology of the Blue Ridge and Piedmont http://www.hydro.geos.vt.edu/ Coastal Plain Piedmont Mesozoic Lowlands Blue Ridge Valley and Ridge Appalachian Plateau Fractured rock aquifers Carbonate rock aquifers Crystalline rock aquifers Evidence of Water Flow in Fractures Coastal Plain Coastal Plain Piedmont Mesozoic Lowlands Blue Ridge Valley and Ridge Appalachian Plateau Public vs. Private Water Supplies PUBLIC SYSTEMS: PRIVATE SYSTEMS: Community water systems may be run by local government, PSA, HOA or private company Considered public system if serving more than 15 service connections/25 people more than 60 days of the year Non-community systems: ◦ Transient (e.g. campground) Wells are considered private if they serve fewer than 25 people Water well construction, location and application regulations vary from state to state (monitoring generally NOT required) Owner is responsible for maintenance, routine water testing, dealing with problems ◦ Non-transient (e.g. school or restaurant) Regulated under Safe Water Act Drinking 15 Public vs. Private Supplies in VA PUBLIC SYSTEMS 38 of Virginia’s 95 counties completely reliant on groundwater; 55 counties draw more than half of supply from groundwater Of Virginia’s 2,900 public supplies, more than 2,300 rely on groundwater; many are small and remote with no alternative to groundwater Monitoring of water quality required at the treatment plant; lead and copper levels must be monitored from tap water samples throughout community PRIVATE SYSTEMS 1.7 million, or 22% of Virginians rely on private water supplies (wells, springs, and cisterns) Private Well Regulations (Va Dept of Health) went into effect in 1992; specify construction, location, and application requirements. Routine testing and maintenance the responsibility of the owner. Homeowners relying on private water supplies: Are responsible for all aspects of water system management Often lack knowledge and resources to effectively manage Usually don’t worry about maintenance until problems arise 16 What about bottled water? Sources vary; municipal (tap), wells, springs…. FDA regulates bottled water that crosses state lines; some concern about enforcement during bottling Additional certifications through IBWA and NSF Expensive! Tap water is about $.01 per 5 gallons; if it cost the same as bottled water, average monthly bill would be $9000 In 2011, $11.1 billion was spent on 9.1 billion gallons of bottled water. Since 2001, consumption has increased 76% in US 167 bottles per person per year! 24% of US bottled water sales are by Dasani (Coke) or Aquafina (Pepsi) 17 Safe Drinking Water Act Passed by Congress in 1974 to protect public health by regulating the nation’s public water supply Authorized EPA to set health-based drinking water standards to protect against natural and man-made contaminants Original focus on treatment to create safe water; 1996 amendments included more proactive steps…… ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Source water protection efforts including surface water systems Evaluation of susceptibility to contamination Operator training Funding for water system improvements Increased public information 18 EPA Drinking Water Standards Primary Standards Secondary Standards • Also called Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) • Cause health problems • Enforced for public systems • 80+ contaminants, including o Nitrate o Lead o Coliform bacteria o Most organic chemicals and pesticides Also called SMCL or RMCL Cause aesthetic problems: o Staining o Taste o Odor Can naturally occur in ground water States can choose to enforce About 15, including: o Iron o pH http://www.epa.gov/safewater/contaminants/index.html 19 Consumer Confidence Reports SDWA requires all community water systems to provide annual reports about the water they distribute From Town of Blacksburg 2008 Report 20 Virginia Drinking Water Regs • Virginia maintains “primacy” to regulate public drinking water supplies • • Virginia Water Control Law (1992) / Virginia Water Control Board Virginia Waterworks Regulations (1995) Virginia Department of Health Office of Drinking Water 21 Source Water Protection Basic concepts apply to public and private sources; consider interaction between the two Groundwater systems: Wellhead Protection ◦ Understanding of groundwater flow to determine recharge areas; extremely complex in Virginia due to geology • Surface water systems: Watershed Protection Three basic steps: 1. 2. 3. Delineate assessment boundaries of a drinking water source Perform inventory of land use activities Determine relative susceptibility of the drinking water source to these activities; may include contingency plans or conservation measures to ensure adequate supply Community involvement essential for success 22 Land use-related Contaminant Sources Private water supplies How does water move to a well? (Bedrock/drilled well) In some parts of Virginia, groundwater moves through fractures, or cracks in the bedrock Water can come from many different directions, depths, and sources into one well It can take water hours, days, or years to move through bedrock Well casing extends through loose “overburden” and into the bedrock, where an “open” borehole continues underground Water can come from any fractures that intersect the open borehole 25 How does water move to a well? (Shallow/bored well) In the Virginia coastal plain, shallow wells drilled in sandy soils are common Because of shorter travel time, water is more susceptible to contamination Well casing extends to bottom of well to below saturated zone Well screen filters sediment from water 26 Well should be at least: ◦ 5 feet from property boundary ◦ 10 feet from building foundation (50 feet if termite treated) ◦ 50 feet from road ◦ 50 feet from sewers and septic tanks ◦ 100 feet from pastures, on-lot sewage system drainfields, cesspools or barnyards Photo credit: Swistock, Penn State Univ Proper private well location Upslope from potential contamination Not in an area that receives runoff 27 Proper private well construction Contract a licensed driller: ◦ Valid Class A, B or C contractor license with WWP (Water Well and Pump) classification Well casing ◦ Minimum of 20’ for bored, 50 – 100’ deep drilled, depending on class of well for 12” Photo credits: SAIF Water Wells ; Penn State University ◦ Extends 12” above ground Grouting to a minimum of 20’ Sanitary well cap or sealed concrete cover Ground slopes away from well 28 The Finished Product – Drilled Well Sealed, sanitary well cap Casing extending >12” above ground surface Ground sloping away from casing Grout seal 29 http://www.omafra.gov.on.ca/english/environment/06-117.htm The Finished Product – Bored Well Sealed concrete cover Casing extending >12” above ground surface Ground sloping away from casing Grout seal http://www.omafra.gov.on.ca/english/environment/06-117.htm 30 Private Well Maintenance Tips Do not use fertilizers, pesticides, oil, or paint around well Keep area around well clean and accessible Keep careful records ◦ original contract, water test results and any maintenance or repair information Every year: ◦ Conduct thorough visual inspection of well ◦ Check cap for cracks, wear and tear, tightness Every 3-5 years have well inspected by a qualified professional (with WWP classification) Groundwater is a SHARED resource! Take personal responsibility! 31 Private Water Supply Regulations • Virginia Private Well Regs o Specify application, inspection and construction requirements o No requirements for maintenance or water testing after construction of well – responsibility of the owner! • EPA National Drinking Water Standards o Apply to PUBLIC systems o Primary (health) and Secondary (nuisance) o Can be used as guidance for private systems to know “how much is too much” 32 Testing water quality Why test? ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Protect family’s health and safety Many contaminants undetectable by human senses Preventive measures often more effective and less expensive Legal protection When to test? ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Routine tests every 1-3 years Pregnant woman or infant in the home Recurring gastrointestinal illness Change in taste, appearance, odor of water Any services or repairs are done 33 What should I test for? Public and private water supply users should consider testing for metals Private supply users: ◦ Every year test for coliform bacteria Indicates possible contamination from human or animal waste ◦ Every three years test: pH (secondary std: 6.5 – 8.5) Total Dissolved Solids (TDS; secondary std 500 mg/L) Other contaminants based on local land uses and water condition Residential Development Bacteria Nitrates Sediment Lawn Chemicals 34 How do I test my water? Participate in a VAHWQP drinking water clinic (private water supply users) Choose a certified laboratory ◦ List available at http://www.vdh.state.va.us/DrinkingWater/laboratories/ Use containers provided and follow directions ◦ Sample bottles often contain fixers- do not rinse ◦ Be aware of time requirements to get samples to lab 35 Understanding test results Most results provided as concentrations: ◦ mg/L (milligrams per liter) ≈ ppm (parts per million) ◦ µg/L = (micrograms per liter) ≈ ppb (parts per billion) Other units unique to test ◦ Bacteria ◦ Radon, hardness, pH 1 ppm = about 4 drops in a 55 gallon barrel! Compare to EPA standards: http://www.epa.gov/safewater/contaminants/index.html 36 Sources of potential contaminants or issues of concern well Surface water contamination: nitrate, bacteria Source may be plumbing materials or existing water treatment device: Where a contaminant comessodium from affects copper how we can deal with lead it! bacteria Some are found in groundwater naturally, either due to human activities on or below ground: arsenic TDS iron hardness 37 Options for problem water 1. If possible, control the source of pollution ◦ Divert runoff from well, maintain septic system 2. Improve maintenance of water system ◦ Install sanitary well cap, slope the ground 3. Treat the water to reduce contaminant concentration ◦ Match the treatment option to the pollutant ◦ Consult a professional 4. Develop a new source of water ◦ Deeper well, develop spring, connect to public water 38 http://static.howstuffworks.com/gif/septic-tank-cleaning-1.jpg, http://www.shipewelldrilling.com/Pictures/well_drilling_rig.jpg, http://www.clearflow.ca/REVERSE_OSMOSIS2.jpg Home Treatment Considerations Be sure to explore ALL of your options Always have water tested by a certified lab Be aware of dishonest businesses – look for NSF (National Sanitation Foundation) and WQA (Water Quality Association) certifications, consult BBB If it sounds too good to be true…it probably is! Point of Use (POU) vs. Point of Entry (POE) Weigh benefits and limitations of device ◦ Cost ◦ Maintenance ◦ Warranty 39 What is the VAHWQP? Established in 1989 County-based Drinking Water Clinics Coordinated with local Extension Agents Kickoff Meeting Homeowners collect sample; samples analyzed at VT lab Interpretation Meeting: test results and recommendations for care, maintenance, and addressing problems ~15,800 samples tested 40 Drinking water clinics • Testing for : • • • • • Total coliform E. coli Nitrate Fluoride Sodium • • • • • • Manganese • Arsenic Copper • Lead pH • Quantification of Total Dissolved Solids bacteria Sulfate $49 per sample Hardness kit 41 VAHWQP Drinking Water Clinics YEAR of LAST CLINIC 2008-2013 (in progress) 2003-2007 1996-2002 1989-1995 No clinic held Virginia Master Well Owner Network (VAMWON) Includes extension agents, agency collaborators, volunteers Training workshops across VA • Groundwater hydrology • Proper well location, construction • • • • • and maintenance Land use impacts and wellhead protection Water testing and interpretation Solving water problems Education and outreach ideas Water conservation VAMWON volunteer outreach: Fairs and home shows Speak to church or civic groups One-on-one conversations with neighbors and friends Write an article for local paper Help with drinking water clinic 43 Virginia Master Well Owners by County - 2013 Trained VAMWON volunteer or agency collaborator in county Loudoun Rappa hannock Trained VAMWON agent in county King George Trained agent and volunteer Augusta Albemarle Bath Louisa Caroline Nelson Amherst Mathews Bedford Giles Prince Edward Campbell Bland Charlotte Wise Smyth Lee Scott Washington Floyd Wythe Franklin Dinwiddie Surry Isle of Wight Norfolk (city) Halifax Carroll Grayson Lancaster Powhatan Patrick Henry Mecklenburg Suffolk (city) Revised 6/11 VAMWON and VAHWQP Impacts • 54 VAMWON agents, 75 volunteers, and 17 agency collaborators representing 59 counties and 4 cities • 59 drinking water clinics in 73 counties since 2008 (3274 samples analyzed serving over 7400 people): • > 80% have never tested or tested only once; wells average 25 years old • 44% of samples positive for total coliform; 11% of samples positive for E. Coli • ~20% have lead present in first draw (from plumbing components) • After participating in a clinic: • 74% will test water annually or every few years • 80% plan to share what they have learned with others • 28% will seek additional testing following clinic • 26% will work to determine source of pollution • 23% will shock chlorinate water system • 18% will pump out septic system 45 2013 Drinking Water Clinics County(ies) Page and Shenandoah Frederick and Clarke Important Dates Contact Information Get Sample Kit Collect Sample Results Meeting 6/10 6/12 7/29 6/17 6/19 7/30 6/24 6/26 7/31 7/15 7/17 8/13 8/5 8/7 9/3 8/12 8/14 9/10 Nottoway 9/9 9/11 10/8 Pittsylvania 9/16 9/18 10/15 Franklin 10/7 10/9 11/5 Loudoun 10/14 10/16 11/12 Caroline 10/21 10/23 11/19 Rockingham 11/11 11/13 12/11 Warren New Kent and Charles City Lunenburg and Charlotte Mecklenburg and Halifax Mark Sutphin masutph2@vt.edu 540-665-6659 John Allison jab10352@vt.edu 804-652-4743 Donna Daniel ddaniel@vt.edu 434-696-5526 Haley McCann hmccann@vt.edu 434-645-9315 Jamie Stowe jnstowe@vt.edu 434-432-7770 Cynthia Martel cmartel@vt.edu 540-483-5161 Corey Childs cchilds@vt.edu 703-777-0373 Catherine Pitts pudney@vt.edu 804-633-6550 Amber Vallotton avallott@vt.edu 540-564-3080 46 Interested in learning more? Come to a drinking water clinic Join Virginia Master Well Owner Network! ◦ Learn more about your own water system and how to protect your water quality and share info with others ◦ Receive 7 hours MG continuing education credits ◦ Apply at: www.wellwater.bse.vt.edu or call Erin ◦ Next Training: Charlottesville – Oct 26, 2013 ◦ At VAMWON training workshop: Free water conservation devices for home and garden Resource binder 47 Erin Ling (wellwater@vt.edu) Brian Benham (benham@vt.edu) www.wellwater.bse.vt.edu Email: wellwater@vt.edu Ph: 540-231-9058 Virginia Cooperative Extension programs and employment are open to all, regardless of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, genetic information, marital, family, or veteran status, or any other basis protected by law. An equal opportunity/affirmative action employer. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Virginia State University, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture cooperating. Edwin J. Jones, Director, Virginia Cooperative Extension, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg; Jewel E. Hairston, Administrator, 1890 Extension Program, Virginia 48 State, Petersburg.