Slaughterhouse-Five is a novel that explores many

advertisement

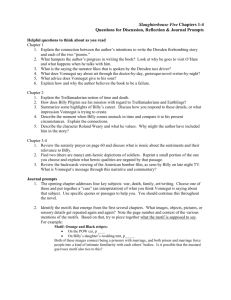

Slaughterhouse-Five Asif Nazerally English ENG4U Tuesday, November 12, 2013 Nazerally 2 By now, many people have realized that life is a very cruel sport. It ventures into areas of depression, anger, and a whole assortment of negativity, but as humans we find several different methods of coping with these incidents whether it be meditation, or simply punching a wall. But the same cannot be said for veterans of war unfortunately, due to the magnitude of the events that lay before them, resulting in a post-war “life” that almost seems to be meaningless. Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut was created simply to depict the post-war crisis that is the “life” experienced by soldiers of war. Following the events of World War II, Billy Pilgrim not only lacks the moral aptitude to recognize the gravity of death, but he acquires a rather tenuous state of mind. The author uses the protagonist to convey his post-war message throughout this autobiographical novel and he also includes his own bad habits that were developed post-war to further convey his message. Slaughterhouse-Five is a novel that explores many different aspects of humankind such as revenge and dignity, but Vonnegut mainly wrote the book to bring to light the negative effects that war brings to a human life, and this is best demonstrated through the protagonist in the novel, Billy Pilgrim. One of the ways that Billy displays the effects of war on his life is his indifference towards death. Billy almost never seems to have anything to say when people are dying around him, and he just passes it off in a nonchalant matter, as part of life. An example of this would be when he is the only survivor (along with the co-pilot) in a plane crash among a group of optometrists: Early in 1968, a group of optometrists, with Billy among them, chartered an airplane to fly them from Ilium to an international convention of optometrists in Montreal. The plane crashed on top of Sugarbush Mountain, in Vermont. Everybody was killed but Billy. So it goes. (Vonnegut 25) Nazerally 3 This plane was supposed to take a group of optometrists to a convention in Montreal, but instead, it resulted in a plane crash. Someone who is the only survivor of the passengers on a chartered plane that had crashed usually undergoes post-traumatic stress disorder of some shape or form. This could be in the case of nightmares, anxiety or even anger. But due to the number of deaths that Billy had already witnessed due to the war he had part in, his dreams only consisted of becoming a giraffe and eating pears: Billy had a dream of giraffes in a garden. The giraffes were following gravel paths, were pausing to munch sugar pears from treetops. Billy was a giraffe, too. He ate a pear. It was a hard one. It fought back against his grinding teeth. It snapped in juicy protest. (Vonnegut 99) This is a dream that Billy has in the hospital after the plane crash. Since this page long description of Billy’s dream does not further the plot whatsoever, it was perhaps solely put in the novel to demonstrate Billy’s apathy towards the whole situation. The author proposes that the only words he had regarding the plane crash was “so it goes”, which was Billy Pilgrim’s method of coping with death. Another example where Billy shows no remorse for a death is when his wife, Valencia Pilgrim, dies of accidental carbon monoxide poisoning on the way to see Billy: Valencia turned off the engine, but then she slumped against the steering wheel, and the horn brayed steadily. A doctor and a nurse ran out to find out what the trouble was. Poor Valencia was unconscious, overcome by carbon monoxide. She was a heavenly azure. One hour later she was dead. So it goes. (Vonnegut 183) Nazerally 4 When Valencia hears that Billy is in the hospital recovering from a plane crash, she speeds over to him in hysterics, resulting in a car accident. Valencia speeds away after getting hit from behind, but unfortunately the exhaust system was destroyed and Valencia dies. After the death of a loved one, most people would undergo an intense amount of grief and pain, but as for Billy, he never ends up speaking to her death for the rest of his life, and once again, only has these words to say: “so it goes”. To further prove the fact that Kurt Vonnegut wrote this novel to show the effects that war has on a soldier’s life afterwards, he really focusses on Billy’s diminished mental state, as a result of war. One prime example that shows the condition of his mind is his inability to separate fantasy from reality, which occurs throughout the novel. Billy believes that he was captured by an alien life form and brought to their planet, Tralfamadore: He said, too, that he had been kidnapped by a flying saucer in 1967. The saucer was from the planet Tralfamadore, he said. He was taken to Tralfamadore, where he was displayed naked in a zoo, he said. He was mated there with a former Earthling movie star named Montana Wildhack. (Vonnegut 25) Billy runs away from his home in Ilium to New York City to get on an all-night radio talk show, and on that talk show, he explains that he was kidnapped on the night of his daughter’s wedding, and taken to the planet Tralfamadore, where he fornicated with a movie star. Billy claims that since Tralfamadorians can pop in and out through moments in time, no one noticed he was gone, since was only for a microsecond. He is then kicked off the news show, clearly because Billy is a lunatic. Billy’s fantasies are the equivalent of anyone else’s meditation, or punch to the wall; it is his method of coping. Unfortunately for Billy, the stress that Billy must Nazerally 5 cope with after the war is on such an enormous scale that he must take a mental vacation to a fantasy in a far world. To prove that Billy’s stories are fictional, the author includes Billy going to a book store that has all the events he believes to have happened to him in different sciencefiction novels, proving that it is fake. Another event that represents Billy’s post-war mental state in this novel is when he endures a nervous breakdown at his eighteenth wedding anniversary: Billy had powerful psychosomatic responses to the changing chords. His mouth filled with the taste of lemonade, and his face became grotesque, as though he really were being stretched on the torture engine called the rack [...] Here was proof that he had a great big secret somewhere inside, and he could not imagine what it was. [Ellipses mine] (Vonnegut 173) After seeing the barbershop quartets singing, the sight of their mouths wide open had reminded him of the German soldiers’ faces when they first witnessed the destruction of Dresden, resulting in his breakdown. Pilgrim did not know why the quartet set him off, until he left to his bedroom and had a chance to reflect: this was the first time he realized the effect the Dresden bombing had on him, the first time in over eighteen years. Once again, to cope with this stress, Billy mentally sets off to Tralfamadore, where he recounts the story to Monica Wildhack. Kurt Vonnegut used the protagonist in the story of Slaughterhouse-Five as a means of portraying the crisis that remains the lives of soldiers after war, but also in the book, he includes some real experiences that following the events of World War II. In the first chapter (which could arguably be used as a preface to the book), Vonnegut speaks to his long journey of actually Nazerally 6 writing this book. Not only that, but he bluntly lets the readers know that after the war, he developed some odd habits: I get drunk, and I drive my wife away with a breath like mustard gas and roses. And then, speaking gravely and elegantly into the telephone, I ask the telephone operators to connect me with this friend or that one, from whom I have not heard in years. (Vonnegut 4) The first example of a bad habit that the first chapter puts forward is Vonnegut’s insomnia. The author points to the fact that after the war, he had many sleepless nights, and on those sleepless nights, he phone the operator and get them to patch him through to one of his old girlfriends, or just old friends. To further illustrate to the reader the insomnia that comes along with post-war life, he, very subtly, points out the insomnia of one of his war buddies, when he calls him up late at night: “I got O'Hare on the line in this way […] He was up. He was reading. Everybody else in his house was asleep” (Vonnegut 4). Not only is Vonnegut the only one awake in his household, but his fellow soldier was also the only member of his family who wasn’t fast asleep. The second example of a bad habit that is displayed in the first chapter is also seen in the quote above: the author’s alcoholism. Not only was he having a problem getting to sleep, but he would drown his saliva with alcohol most nights. He also speaks to the fact that sometimes, he may get drunk and have a conversation with his dog: “'You're all right, Sandy, I'll say to the dog. ‘You know that, Sandy? You're O.K.'” (Vonnegut 7). These are just two of the bad examples that Kurt Vonnegut chose to include in his book to show the lasting, negative effect of war. Nazerally 7 Nazerally 8 Works Cited Vonnegut, Kurt. Slaughterhouse-Five. New York: Dell Publishing, 1968. Print.