Child Abuse for the Primary Care Physician

advertisement

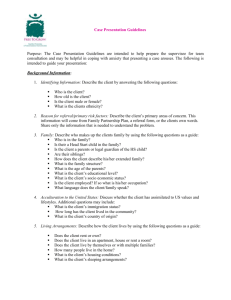

TM TM Prepared for your next patient. Child Abuse for the Primary Care Physician Cindy W. Christian, MD Director, Safe Place: The Center for Child Protection and Health The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia TM Disclaimers Statements and opinions expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Mead Johnson sponsors programs such as this to give healthcare professionals access to scientific and educational information provided by experts. The presenter has complete and independent control over the planning and content of the presentation, and is not receiving any compensation from Mead Johnson for this presentation. The presenter’s comments and opinions are not necessarily those of Mead Johnson. In the event that the presentation contains statements about uses of drugs that are not within the drugs' approved indications, Mead Johnson does not promote the use of any drug for indications outside the FDA-approved product label. TM Objectives Improve early diagnosis of child abuse by recognizing clinical presentations. Increase comfort with the medical evaluation of the sexually abused child. Identify diseases that may mimic abuse. Improve diagnosis using appropriate laboratory and radiographic tests. Highlight the importance of interdisciplinary cooperation in protecting children. TM Child Abuse is a Public Health Problem 3 million reports annually to child welfare Almost 1 million confirmed cases annually More than 1,500 deaths annually from maltreatment Lifelong morbidity – The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study – Emerging research on the effects of early childhood trauma on the developing brain Pediatricians as sentinels – Challenges to identification TM Child Physical Abuse: Clues to Diagnosis Magical injuries History inconsistent with injuries Child’s development inconsistent with reported mechanism of injury Unexpected or unexplained delay in seeking care Pathognomonic injuries Injuries in young infants TM Facial Bruising Percentage of Children with Bruises by Age (n=930) 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 0-2 mo 3-5 mo 6-8 mo 9-11 mo 12-14 15-17 18-23 24-35 mo mo mo mo Sugar NF, Taylor JA, Feldman KW, and the Puget Sound Pediatric Research Network. Bruises in infants and toddlers: those who don’t cruise rarely bruise. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(4):399–403 TM Frenum Injuries TM Missed Opportunities for Identification Jenny C, Hymel KP, Ritzel A, et al. Analysis of missed cases of abusive head trauma. JAMA. 1998;281(7):621–626 – 1/3 of children with abusive head trauma missed by health care professionals • Young infants, mild signs and symptoms • Misread radiographs • Caucasian, 2-parent households Lane WG, Ruben DM, Monteith R, et al. Racial differences in the evaluation of pediatric fractures for physical abuse. JAMA. 2002;288(13):1603–1609 – Racial differences in obtaining skeletal surveys and reports to Child Protective Services TM The Search for Additional Injuries Skeletal Survey – Oblique rib films – Follow-up skeletal surveys Complete blood count (CBC) with differential Liver function tests, amylase, lipase, urinalysis Toxicology Brain imaging – Computed tomography for symptomatic infants – Magnetic resonance imaging for asymptomatic infants • Approx. 1/3 of asymptomatic infants and children with cranial / intracranial injury Rubin DM, Christian CW, Bilaniuk LT, et al. Occult head injury in high risk abused children. Pediatrics. 2003;111(6):1382–1386; Laskey AL, Holsti M, Runyan DK, et al. Occult head trauma in young victims of physical abuse. J Pediatr. 2004;144(6):719–722 TM Yield of Skeletal Surveys Retrospective study of 703 consecutive skeletal surveys 10.8% with positive results – – – – Infants younger than 6 months (16% with positive skeletal survey) Infants with apparent life-threatening event (ALTE) (12/66: 18%) Infants with seizures (6/18: 33%) Children with suspected abusive head trauma (AHT) (20/88: 23%) With positive skeletal survey, 79% with ≥1 healing fracture In 50% of cases, skeletal survey influenced ultimate diagnosis Duffy SO, Squires J, Fromkin JB, et al. Use of skeletal surveys to evaluate for physical abuse: analysis of 703 consecutive skeletal surveys. Pediatrics. 2011;127(1):e47–e52 TM Searching for Fractures: Who Requires Skeletal Imaging? Children younger than 2 years of age with abusive injuries – Children with AHT – Battered children – Children with inflicted burns Children with “concerning” injuries or findings – – – – All infants with injury? Infants with skull fractures? Infants with ALTEs? Infants with seizures? Twins of abused children – Young siblings, household members of abused children? TM Causes of Injuries in Children <36 Months of Age With Fractures in the 2003 KID Cause Weighted N = 15,143 Proportion (%) Fall 50.42 Abuse 12.08 Other accident 11.60 Motor vehicle accident 11.40 Uncertain whether accidental or intentional 2.17 Bone abnormality 0.85 Metabolic abnormality 0.12 Birth trauma 0.05 No injury E-code 11.32 Total 100.01 Abbreviation: KID, Kids’ Inpatient Database Leventhal JM, Martin KD, Asnes AG. Incidence of fractures attributable to abuse in young hospitalized children: results from analysis of a United States database. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):599–604 Weighted Proportions of Fractures Attributable to Abuse, According to Age and Bone, in the 2003 KID Ribs Radius/ulna Tibia/fibula Humerus Femur Clavicle Skull 0–11 mo % from # Fractures Abuse 809 69.4 261 493 518 1257 227 3363 62.1 58.0 43.1 30.5 28.1 17.1 0–36 mo % from # Fractures Abuse 1001 61.4 657 1069 3172 4026 388 5886 29.8 31.1 9.3 11.7 20.7 12.1 Leventhal JM, Martin KD, Asnes AG. Incidence of fractures attributable to abuse in young hospitalized children: results from analysis of a United States database. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):599–604 TM Differential Diagnosis of Physical Abuse There is a differential diagnosis for every individual injury! – There are pathognomonic patterns of injury. Medical evaluation Child protection TM Initial Screening for Cutaneous Bleeding Screening for coagulopathy – CBC with platelet count – Prothrombin time (PT) / activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) / international normalized ratio (INR) – Factor VIII level – Factor IX level – von Willebrand Factor antigen – Ristocetin cofactor TM Evaluation for Children with Suspicious Fractures Careful evaluation of radiographs – Skeletal survey for infants and young children Screen for mineralization deficiency – Calcium, phosphate, alkaline phosphatase – Consider 25-hydroxy vitamin D, parathyroid hormone – Consider urine calcium, phosphate Consider genetic testing for osteogenesis, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Menkes disease – Can also consider fibroblast collagen analysis Work with consultants TM Child Sexual Abuse Involvement of children in sexual activities that… – – – – They cannot understand They are not developmentally prepared for They cannot give informed consent for Violate societal taboos Perpetrators – Known to child – Intend not to injure child – Intend to maintain secrecy TM Child Sexual Abuse: Presentation for Medical Care Disclosure of inappropriate sexual contact Behavioral concerns Physical injury to genitals Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) TM Examples of Sexual Behaviors in Children 2 to 6 Years of Age aAssessment of situational factors (family nudity, child care, new sibling, etc.) contributing to behavior is recommended. of situational factors and family characteristics (violence, abuse, neglect) is recommended. cAssessment of all family and environmental factors and report to child protective services is recommended. bAssessment Kellogg ND and the American Academy of Pediatric Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. The evaluation of sexual behaviors in children. Pediatrics. 2009;124(3):992–998 TM Genital Examination of the Sexually Abused Child NORMAL exams are the NORM – – – – For both girls and boys Abuse may not have injured the genitals. Abuse may not have involved the genitals. Injuries may have healed. Hours after assault 3 weeks post assault TM Medical Evaluation of Child Sexual Abuse Medical history – From parent; alone with child Complete physical examination – Chaperone Genital examination – Careful documentation STI screening – Urine nucleic acid amplification tests – Additional testing as indicated Refer acute assault to emergency department / critical ambulatory care TM Acting on Suspicion TM Informing the Family: Concern for the Child TM The Pediatrician’s Role in Protecting Children Sentinels for identifying abuse – Honest discussions with parents Reporters of suspected abuse – Cooperating with investigations Supporter of families and children – Non-offending parents Prevention – – – – Identify families eligible for prevention programs Education about infant crying early and often Education about body safety Providing anticipatory guidance for behavioral problems TM Child Abuse Resources on PCO AAP Textbook of Pediatric Care https://www.pediatriccareonline.org/pco/ub/view/AAP-Textbook-of-PediatricCare/394120/all/chapter_120:_child_physical_abuse_and_neglect and https://www.pediatriccareonline.org/pco/ub/view/AAP-Textbook-of-PediatricCare/394122/0/Chapter_122:_Sexual_Abuse_of__Children Point of Care Quick Reference https://www.pediatriccareonline.org/pco/ub/view/Point-of-Care-QuickReference/397132/all/apparent_life_threatening_event Patient Handouts https://www.pediatriccareonline.org/pco/ub/index/Patient_Handouts_AAP/Keyw ords/C/child_abuse TM For more information… On this topic and a host of other topics, visit www.pediatriccareonline.org. Pediatric Care Online is a convenient electronic resource for immediate expert help with virtually every pediatric clinical information need. Musthave resources are included in a comprehensive reference library and timesaving clinical tools. • Haven't activated your Pediatric Care Online trial subscription yet? It's quick and easy: simply follow the steps on the back of the card you received from your Mead Johnson representative. • Haven't received your free trial card? Contact your Mead Johnson representative or call 888/363-2362 today.