ADHD - American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

advertisement

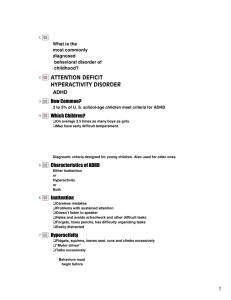

The Diagnosis and Treatment of ADHD Jess P. Shatkin, MD, MPH Vice Chair for Education NYU Child Study Center New York University School of Medicine Learning Objectives Residents will be able to: 1. Identify symptom criteria for ADHD. 2. State the major rule-out diagnoses. 3. Identify the primary comorbidities. 4. Describe the diagnostic process. 5. Choose between various treatment options based upon their risk/benefit profiles. The Story of Fidgety Phillip --Dr. Heinrich Hoffman, 1844 "Let me see if Philip can Be a little gentleman; Let me see if he is able To sit still for once at table." Thus spoke, in earnest tone, The father to his son; And the mother looked very grave To see Philip so misbehave. But Philip he did not mind His father who was so kind. He wriggled And giggled, And then, I declare, Swung backward and forward And tilted his chair, Just like any rocking horse;"Philip! I am getting cross!" History of ADHD Minimal Brain Dysfunction (damage): 1900 – 1950 Hyperkinetic/Hyperactivity Syndrome (DSM-II of 1968): 1950 – 1969 Recognition of Attentional impairment and Impulsivity: 1970 – 1979 Diagnostic Criteria (DSM-III) and “ADD” with or without Hyperactivity: 1980 ADD becomes ADHD (DSM-IIIR) w/mixed criteria: 1987 ADHD (inattentive, hyperactive, combined subtypes) in DSM-IV: 1994 Differential Diagnosis (Psychiatric) Mood and/or Psychotic Disorder Anxiety Disorder Learning Disorder Mental Retardation/Borderline IQ ODD/Conduct Disorder Pervasive Developmental Disorder Substance Abuse Axis II Disorders Psychosocial Cx (e.g., abuse, parenting, etc.) Differential Diagnosis (Medical) Seizure Disorder (e.g., Absence, Complex-Partial) Chronic Otitis Media Hyperthyroidism Sleep Apnea Drug-Induced Inattentional Syndrome Head Injury Hepatic Illness Toxic Exposure (e.g., lead) Narcolepsy DSM-IV Diagnostic Criteria (Inattention) Makes careless mistakes/poor attention to detail Difficulty sustaining attention in tasks/play Does not seem to listen when spoken to directly Difficulty following instructions Difficulty organizing tasks/activities Avoids tasks requiring sustained mental effort Loses items necessary for tasks/activities Easily distracted by extraneous stimuli Often forgetful in daily activities DSM-IV Diagnostic Criteria (Hyperactive/Impulsive) Fidgets Leaves seat Runs or climbs excessively (or restlessness) Difficulty engaging in leisure activities quietly “On the go” or “driven by a motor” Talks excessively Blurts out answers before question is completed Difficulty waiting turn Interrupts or intrudes on others DSM-IV Functional Criteria 6 of 9 symptoms in either or both categories Code as: Inattentive; HyperactiveImpulsive; or Combined Type Persisting for at least 6 months Some symptoms present before 7 y/o Impairment in 2 or more settings Social/academic/occupational impairment Epidemiology (1) Most commonly diagnosed behavioral disorder of childhood (1 in 20 worldwide) 3 – 7% of school children are affected in U.S. Males:Females = 2 – 9:1 Virtually all neurodevelopmental disorders are more common in boys prior to age 10 years; by adulthood, we get closer to 1:1 ratios Epidemiology (2): Gender Paradox Girls typically show less hyperactivity, fewer conduct problems, & less externalizing behavior Yet we see a gender paradox – The group with the lower prevalence will show a more severe clinical presentation, along with severity/greater levels of comorbidity (Loeber & Keenan, 1994) – Consistent with multifactorial/polygenic conditions: The idea is that it takes a greater accumulation of vulnerability and risk factors to put an individual from the lower-afflicted group “over the top” Epidemiology (3) At least 30 – 50% maintain diagnosis for ≥ 15 yr Strongest predictor of poor prognosis is prepubertal aggression Over 80% of psychotropics are Rx by PCPs: stimulants (>50%), antidepressants (30%), mood stabilizers (13%), anxiolytics (7%), & antipsychotics (7%) ADHD related outpatient visits to PCPs increased from 1.6 – 4.2 million between 1990 93 Too Much of a Good Thing? Between 1991 – 2000, the annual production of MPH rose by 740%; production of amphetamine increased 25x during this same period. In 2000, America used 80% of the world’s stimulants; most other industrialized countries use 1/10 the amount we do. Canada uses stimulants at 50% of the US rate. Rates vary by states and regions: Hawaii has the lowest per capita MPH use by a factor of 5. “Hot spots” are mostly in the east near college campuses and clinics that specialize in Dx/Rx. But wait, there’s more! Approximately 2.5 million children in the US (ages 4 – 17) took medication for ADHD in 2004 Sales of medications used to treat ADHD rose to $3.1 billion in 2004 from $759 million in 2000 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2008 3.5% of US children (2.8 million kids) aged 18 and younger received a stimulant medication in 2008, up from 2.9% in 1996 Stimulant use in girls increased over 10 years from 1.1% to 1.6% Stimulant use in preschoolers decreased, stayed the same for 6 – 12 y/o, and increased for adolescents Hey, Kids Can’t Have All the Fun! Adult use of these medications increased 90% between March 2002 and June 2005…can you say Strattera?! Use of meds to treat ADHD in adults aged 20 – 44 rose 19% in 2005 An estimated 1.7 million adults aged 20 – 64 and 3.3 million children under 19 took medication for ADHD in 2005 – Use increased 2% for those 10 – 19 – Use decreased by 5% for those under 10 ADHD is Familial Family studies: (1) sibling risk increases 2-5x; (2) 3-5x increased likelihood that parent is affected (9 – 35%) Symptom Evolution Inattention Hyperactivity Impulsivity Time ADHD: Course of the Disorder Inattention —Age— Why More ADHD? Improved recognition by physicians? Increase in prevalence? An easing of standards for making the diagnosis? An easing of standards for prescribing medication?...or the “Prozac” connection? Increased scholastic demands? Changing parental habits? Managed care and the pharmaceutical industry? 1991 amendments to IDEA? Potential Areas of Impairment Academic limitations Relationships Occupational/ vocational Legal difficulties ADHD Motor vehicle accidents Low self esteem Injuries Smoking and substance abuse Comorbidities (1) 2/3 of children with ADHD present with ≥ 1 comorbid Axis I disorder: Comorbidities (2) ≥ 84% of children with ADHD demonstrate psychopathology as adults Adolescents w/ADHD Rx w/stimulants have lower rates of substance abuse than untreated adolescents w/ADHD Educational impairments Employment problems Greater sexual-reproductive risks Greater motor vehicle risks Natural History Rule of “thirds”: – 1/3 complete resolution – 1/3 continued inattn, some impulsivity – 1/3 early ODD/CD, poor academic achievement, substance abuse, antisocial adults Age related changes: – – – – Preschool (3-5 y/o) – hyperactive/impulsive School age (6-12 y/o) – combination symptoms Adolescence (13-18 y/o) – more inattn w/restlessness Adult (18+) – largely inattn w/periodic impulsivity Neuroimaging Brain Imaging and ADHD Numerous imaging studies have now demonstrated the following: – The caudate nucleus and globus pallidus (striatum) which contain a high density of DA receptors are smaller in ADHD than in control groups – ADHD groups have smaller posterior brain regions (e.g.,occipital lobes) – Areas involved in coordinating activities of multiple brain regions are (e.g., rostrum and splenium of corpus collosum and cerebellar vermis) are smaller in ADHD Developmental Trajectories of Brain Volume Abnormalities in Youth with ADHD Smaller brain volumes in all regions regardless of medication status (cortical white & gray matter) Smaller total cerebral (-3.2%) and cerebellar (3.5%) volumes Volumetric abnormalities (except caudate) persist with age No gender differences Volumetric findings correlate with severity of ADHD • Castellanos et al, 2002 Cortical Thickness in ADHD: Cingulate Cortex Makris et al. Cerebral Cortex 2006 Shaw et al., Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006 Specific Genes Associated w/ADHD Rare mutations in the human thyroid receptor β gene on chromosome 3 Dopamine Transporter gene (DAT) on chromosome 5 Symptoms suggestive of ADHD are found among those w/a general resistance to thyroid hormone (Hauser et al, NEJM, 1993) A “hyperactive” presynaptic DAT (Gill et al, Mol Psych, 1997) Dopamine Receptor D4 gene (DRD4) on chromosome 11 Postsynaptic malfunction do not allow signal transmission (Swanson et al, Mol Psych, 1998) Cortical Thickness & DRD4 Shaw et al. AGP 2007 Potential Non-Genetic Causes Non-genetic causes of ADHD are also neurobiological in nature – Perinatal stress – Low birth weight – Traumatic brain injury – Maternal smoking during pregnancy – Severe early deprivation (extreme) • Nigg, 2006 Executive Functioning Most children with ADHD have impairments in executive functioning, including: – Response inhibition – Vigilance – Working memory – Difficulties with planning • Wilcutt et al, 2005 Neuropsychological Testing Nigg (2005) in a meta-analysis identified the most common abnormalities in various neuropsych tasks in ADHD (listed by Effect Size): – Spatial working memory (0.75) – CPT d-prime (0.72) – Stroop Naming Speed (0.69) – Stop Task Response Suppression (0.61) – Full Scale IQ (0.61) – Mazes, a planning measure (0.58) – Trails B Time (0.55) Establishing a Convincing Diagnosis (1) There is no single test to identify ADHD Available “tests” are primarily Continuous Performance Tests (CPTs): – – – – TOVA (Test of Variables of Attention) Conner’s CPT Gordon Computerized Diagnostic System I.V.A. CPT Diagnosis must be multi-factorial Establishing a Convincing Diagnosis (2) Clinical Interview: – Diagnostic Assessment of Primary Complaint – Review of Psychiatric Systems (e.g., attention, hyperactivity/impulsivity, oppositional & conduct difficulties, mood, anxiety, psychosis, trauma, neurovegetative systems, tics, substance abuse, etc.) – Medical, Psychiatric, & Developmental History – Detailed Educational History – Detailed Family & Social History Establishing a Convincing Diagnosis (3) Collateral interviews: – – – – – – – – Patient Primary Caregivers (parents, grandparents, etc.) Teachers School Counselors Sunday School Teachers Coaches Music Teachers Camp Counselors (e.g., Boys & Girls’ Club) Establishing a Convincing Diagnosis (4) “Some” symptoms by age 7 years This criterion has been maintained in 3 versions of the DSM, despite a lack of empirical support Likely leads to increased false-negatives DSV-IV field trials demonstrated that inattentive subtype exhibited a later onset (Applegate et al, 1997) An adult population survey found that only 50% of individuals with clinical features of ADHD retrospectively reported symptoms by age 7, but 95% reported symptoms before age 12 & 99% before 16 (Kessler et al, 2005) DSM-V will possibly reset age to 12 years to decrease rate of false negatives (Kieling et al, 2010) Establishing a Convincing Diagnosis (5) Symptoms in ≥ 1 setting: – Never diagnose ADHD in a 1:1 interview – Individuals with ADHD can often function well in certain settings with no signs of symptoms when they are interested and maintain total focus (e.g., playing Nintendo, watching videos, etc.) – Symptoms in group settings are a must! Establishing a Convincing Diagnosis (6) Rating scales: – – – – – – – SNAP – IV (for parents & teachers) Conners (for teachers, parents, and affected adults) ACTeRS (for teachers & parents) Child Behavior Checklist Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC) ADHD Rating Scale – IV Brown ADD Scales Establishing a Convincing Diagnosis (7) Treatment trial: – Risk of adverse effects is significant – Not necessarily “diagnostic” even if effective – At least 2 – 3 medications should be attempted before patient deemed non-responder – Very low placebo response with treatment of ADHD Who “Gets” ADHD? Children without insurance receive less attention (e.g., care) in all domains Latino and black children are less likely to be diagnosed with ADHD by parent report than are white children Black children with ADHD are less likely to receive stimulants than white children *1997 – 2001 National Health Interview Surveys *1997 – 2000 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Treatment (1) Medication Behavioral Therapy – Cognitive/Behavioral Therapy – Parent Management Training – Social Skills Training Educational Support – 504 – Individual Educational Plan (IEP) Treatment (2): The MTA Study of 1999 Over 550 school-aged children with ADHD were followed for 14 months: 1) Community Treatment 2) Rigorous Medication Protocol 3) Rigorous Behavioral Protocol 4) Combined Behavioral and Medication Protocols Treatment (3) The MTA Study demonstrated: – Medication (stimulants) treatment effective – Behavioral treatment not effective for core ADHD symptoms (useful for some related impairments) – More frequent & higher dosing led to greater responses – Increased physician contact improved outcome Treatment (4) After 14 month initial MTA study, all follow ups were naturalistic (patients could choose any treatment) 2-Year Follow Up of MTA Study: – Modest advantages for Meds & Combined Rx over Behavior Rx & Community Care (effect sizes were reduced by about ½ in comparison to 14 month follow up) 3-Year Follow Up of MTA Study: – 485 of original 579 subjects participated – No differences between groups at 36 months on any measure (parent/teacher ADHD & ODD symptoms, reading achievement scores, social skills, & functional impairment) – Note: Compliance waned over time for med group (used IR meds, not ER); medication treatment intensity group was dropped after 14 months; initial medication only group decreased medication use (91% to 71%) & behavioral only group increased medication use (14% to 45%) • Jensen et al 2007 Treatment (5) 8-Year Follow Up of MTA Study: – 436 of original 579 subjects participated – No differences between groups at 6 & 8 years on any measure (parent/teacher ADHD & ODD symptoms, reading achievement scores, social skills, & functional impairment, along with new variables: grades, arrests, & psych hospitalizations) – Note: Medication use decreased by 62%, but adjusting for this did not change the outcome. Type or intensity of treatment in the first 14 months did not predict functioning at 6 and 8 years later. ADHD symptom trajectory over the first 3 years did predict 55% of the outcomes. Children with behavioral and sociodemographic advantage and with the best response to any treatment will have the best long-term prognosis. • Molina et al 2009 Comorbidity in the MTA Study ADHD alone ODD 179 126 15 Tic 14 5 Conduct 43 12 8 4 1 3 67 2 11 Mood 5 26 Anxiety 58 Stimulants (1): Mechanism of Action Reuptake inhibition of NE & DA Cause increased release of presynaptic NE/DA Amphetamine promotes passive diffusion of NE and DA into synaptic cleft Amphetamine promotes release of NE and DA from cytoplasmic pools Amphetamine & Methylphenidate are mild inhibitors of MAO Mechanism of Action of Stimulants Presynaptic Neuron Amphetamine blocks vv Storage vesicle Cytoplasmic DA Amphetamine blocks reuptake DA Transporter Synapse Wilens T, Spencer TJ. Handbook of Substance Abuse: Neurobehavioral Pharmacology. 1998;501–513 Methylphenidate blocks reuptake Stimulants (2): Response Rates 70% response rate w/a single stimulant (DEX/MPH); 90% respond if both tried No significant differences between Dexedrine, Adderall, and Methylphenidate overall Behavioral rebound 6 of 8 studies (involving 241 children ) in preschool age (3 - 6 y/o) found MPH effective; no studies w/ADD & DEX (paradoxically FDA approved for preschool children) Stimulants (3): Tachyphylaxis Serum Level Methylphenidate IR 3x/daily Ritalin SR Time (Hours) Stimulants (4): Tachyphylaxis & Successful Long Acting Stimulants Serum Level Long Acting Stimulant Ritalin SR Time (Hours) Methylphenidate IR 3x/daily Stimulants (5): Dosage & Administration Routine PE prior to initiation of stimulants; Vitals checked periodically Long-acting treatments (e.g., Concerta, Ritalin LA, Adderall XR, Metadate CD) are good options given concerns about tachyphylaxis Dosing averages: 30 mg/d MPH, 20 mg/d AD Ritalin LA & Adderall XR are good long-acting choices for those with difficulty swallowing pills Stimulants (6): Dosage and Administration Continued Weight based dosing (not generally utilized) – Methylphenidate @ 1 mg/kg – Adderall @ 0.6 mg/kg Dose to clinical response Forced Dosage Titration – E.g., for a 100+ pound child: Concerta: 18 mg/d week #1; 36 mg/d week #2; and 54 mg/d week #3 – E.g., for a 50 pound child: Adderall XR: 5 mg/d week #1; 10 mg/d week #2; and 15 mg/d week #3 Long Term Effects on Academic Success Mayo Clinic 18 year study (2008) of >5,000 children from birth (370 with ADHD, 277 boys & 93 girls) found that treatment with prescription stimulants is associated with improved long-term academic success of children with ADHD. Girls and boys with untreated ADHD were equally vulnerable to poor school outcomes. By age 13, on average, stimulant dose was modestly correlated with improved reading achievement scores. Both treatment with stimulants and longer duration of medication were associated with decreased absenteeism. Children with ADHD who were treated with stimulants were 1.8 times less likely to be retained a grade than children with ADHD who were not treated. – Barbaresi et al, 2008 Are Stimulants Protective? Certainly with regard to SUDS 10-year, prospective study of 112 white males with ADHD ages 6 to 17 years 82 (73%) had received stimulant treatment, with a mean treatment duration of six years In comparison with those who never took stimulants, participants who had received stimulant medication were significantly less likely to subsequently develop MDD (24% versus 69% for those who were stimulant naïve), conduct disorder (22% versus 67%), oppositional defiant disorder (40% versus 88%) and multiple anxiety disorders (7% versus 60%) Children receiving stimulant therapy also had significantly lower lifetime rates of grade retention as compared to their counterparts who never received stimulants (26% versus 63%) --Biederman et al, 2009 Stimulants (7): Side Effects & Contraindications Side Effects: Nausea, headache, early insomnia, decreased appetite; tics, anxiety, HTN/tachycardia, psychosis Preschool Study of ADHD (PATS) demonstrated a 20% decrease in expected height and 55% decrease in expected weight over 1 year of treatment Contraindications: HTN, symptomatic cardiovascular disease, glaucoma, hyperthyroidism, tics/Tourette’s (relative), drug abuse (relative), psychosis (relative) Stimulants (8): Sudden Cardiac Death Concerns about the cardiac safety of stimulants peaked in 2005 when Health Canada discontinued sales of Adderall XR. FDA discovery of 25 reports of death among users of stimulants between 1999 and 2003 and 54 cases of serious CV problems (e.g., strokes, MI, arrhythmia). Based on 110 million Rx for MTP written for 7 million kids between 1992 – 2005, the estimated rate of SCD among treated patients was 2 – 5 times below the rate in the general population The risk of dying of a sudden cardiac event is still under 1/1,000,000 and no more than is expected in an untreated population. AHA/AAP Recommendations The American Heart Association released on April 21, 2008 a statement about cardiovascular evaluation and monitoring of children receiving drugs for the treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). 1. The scientific statement included a review of data that show children with heart conditions have a higher incidence of ADHD. 2. Because certain heart conditions in children may be difficult (even, in some cases, impossible) to detect, the AAP and AHA feel that it is prudent to carefully assess children for heart conditions who need to receive treatment with drugs for ADHD. 3. Obtaining a patient and family health history and doing a physical exam focused on cardiovascular disease risk factors (Class I recommendations in the statement) are recommended by the AAP and AHA for assessing patients before treatment with drugs for ADHD. 4. Acquiring an ECG is a Class IIa recommendation. This means that it is reasonable for a physician to consider obtaining an ECG as part of the evaluation of children being considered for stimulant drug therapy, but this should be at the physician's judgment, and it is not mandatory to obtain one. 5. Treatment of a patient with ADHD should not be withheld because an ECG is not done. The child's physician is the best person to make the assessment about whether there is a need for an ECG. 6. Medications that treat ADHD have not been shown to cause heart conditions nor have they been demonstrated to cause sudden cardiac death. However, some of these medications can increase or decrease heart rate and blood pressure. While these side effects are not usually considered dangerous, they should be monitored in children with heart conditions as the physician feels necessary. Conflicting Data…sort of… Retrospective, case-control study; children who died of sudden unexplained death were matched to children who died in MVAs Medical, historical, and toxicology info was collected Children with identified heart abnormalities and family history of SCD were excluded Of 564 cases, 10 (1.8%) of cases of sudden unexplained death were treated with a stimulant at the time of death, as compared with only two (0.4%) who died by MVA Gould et al, 2009 Stimulants (9): Pros & Cons Methylphenidate (Ritalin), Adderall, Dexedrine Pros: – Highly effective – Long history of use Cons: – Limited duration of action – Side effects [e.g., Nausea, headache, insomnia, decreased appetite, tics (up to 65% w/MPH), anxiety, HTN/tachycardia, psychosis] – Contraindications [HTN, symptomatic cardiovascular disease, glaucoma, hyperthyroidism, tics/Tourette’s (relative), drug abuse (relative), psychosis (relative)] Stimulants (10): Standard Care Routine Treatment with Stimulants and Atomoxetine – Prior to treatment – Height, weight, Blood Pressure & Heart Rate Cardiac Exam Family history of sudden cardiac death and/or personal or family history of syncope, chest pain, shortness of breath, or exercise intolerance warrants an ECG and pediatric cardiology referral for an echo During Treatment At least annual height & weight (compare to published norms); if height for age decreases by > 1 standard deviation while on stimulants, refer to a pediatric endocrinologist (re: possible growth hormone deficiency or hypothyroidism) Repeat blood pressure and heart rate at least twice annually and anytime prior and subsequent to a dosage increase Tic Disorders Up to 65% of children initiating Rx with MPH may develop a transient tic Simple Motor, Complex Motor, or Vocal Stimulants may cause or “unmask” tics Treatment: Alteration in stimulant dose, discontinuation of stimulant, change of stimulant, α-2 agonists, antipsychotics, CBT, Strattera(?) -2 Agonists (1): Mechanism of Action Increased basal activity of the locus coeruleus noradrenergic cell bodies in patients with ADHD may decrease the response of the PFC Consequently, treatments that reduce locus coeruleus activity (e.g,. clonidine, guanfacine) have been hypothesized to improve attentional, arousal, and cognitive processes (Pliszka et al, 1996) Clonidine binds to the three subtypes of alpha (2) -receptors, A, B and C, whereas guanfacine binds more selectively to post-synaptic alpha (2A) - receptors, which appears to enhance prefrontal function Stimulation of the post-synaptic alpha-2A receptors is thought to strengthen working memory, reduce susceptibility to distraction, improve attention regulation, improve behavioral inhibition, and enhance impulse control -2 Agonists (2): Dosage, Treatment, and Side Effects Useful for residual hyperactivity & impulsivity, insomnia, treatment emergent tics, & aggression Clonidine (0.1 – 0.3 mg/d) & Guanfacine (1 – 3 mg/d) Routine PE/VS prior to initiation of Rx Contraindications: CAD, impaired liver/renal function Side Effects: Rebound HTN/tachycardia, HOTN, sedation, dizziness, constipation, H/A, fatigue Dosage: Start with HS and titrate toward morning Monitor BP, but ECG not routinely necessary -2 Agonists (3):Supporting Data Clonidine (Catapres) – DBPC (age range, 7–12 years) randomized to 4 groups (clonidine, methylphenidate, clonidine plus methylphenidate, or placebo) found at 16 weeks that teachers did not find improvement in the clonidine-only group but did indicate statistically significant improvement in both methylphenidate groups. Parents of children in the clonidine-only group, but not the methylphenidate-only group, reported significant symptom improvement (Palumbo et al, 2008, n =122) – DBPC shows benefit with and w/out MPH in children with Tourettes in reducing ADHD & tics (Tourette’s Study Group 2003, n = 136) – DBPC shows benefit in children w/comorbid MR (Agarwal et al 2001, n = 10) – Conners et al 1999 meta-analysis shows decreased effect size compared to stimulants -2 Agonists (4):Supporting Data Guanfacine (Tenex) – RDBPC trial of 345 patients shows benefit in treatment of ADHD in children (6-17) using longacting Tenex at 2, 3 & 4 mg/day; greatest benefit at highest dose. The change from baseline in patients with the inattentive ADHD subtype was not statistically significant. Younger children (age range, 6–12 years) had greater responses to guanfacine than did adolescents (age range, 13–17 years). Only 62% of all enrolled patients completed the study largely due to fatigue, somnolence, and sedation (Biederman et al, 2008, n = 345) – DBPC shows benefit in treatment of ADHD in children w/comorbid tic d/o (Scahill et al 2001 n = 34) – DBPC shows benefit in adults w/ADHD comparable to dexedrine (Taylor et al 2001, n = 17) Intuniv Guanfacine ER (Shire) Nonscheduled, alpha-2A receptor agonist indicated for ADHD Indicated for children and adolescents, ages 6 – 17 years, as solo treatment or as augmenting medication to stimulants Available in November of 2009 Dosages of 1, 2, 3, and 4 mg once daily In clinical trials, Intuniv significantly reduced ADHD symptoms across a full day as noted by teachers (10 AM and 2 PM) and doctors (throughout the day) and as measured by parents at 6 PM, 8 PM, and 6 AM the following morning Two randomized, DBPC trials: the first trial incorporated 345 children on either placebo or a 2, 3, or 4 mg dose once daily for 8 weeks; the second was a DBPC trial in which 324 children were given placebo or 1 – 4 mg per day for 9 weeks (1 mg given to children <50 kg). Doses increased in both trials at 1 mg per week to treatment effect. Clinically significant improvement noted in 1-2 weeks. α-2 Agonists (5): Pros & Cons Clonidine (Catapres) and Guanfacine (Tenex) Pros: – Moderately effective (residual hyperactivity & impulsivity, insomnia, treatment emergent tics, & aggression) Cons: – Side Effects: Rebound HTN/tachycardia, HOTN, sedation, dizziness, constipation, H/A, fatigue, sudden death in combination with stimulants? – Contraindications: CAD, impaired liver/renal function Combination Treatment Stimulant + α-2 Agonist: – Concern related to 4 reported deaths in children taking both MPH & Clonidine (each with extenuating circumstances) – No FDA limitations – AACAP recommends against routine ECGs Stimulant + TCA: – 9 deaths reported in children taking TCAs – recent report of 10 y/o on DEX and IMI who died by cardiac arrhythmia Tricyclics for ADHD DBPC trials: – Desipramine in adults w/68% positive responses (Wilens et al 1996, n = 41) – Desipramine w/comorbid tic d/o in children & adolescents (Spencer et al 2002 n = 41); 71% of pts w/ADHD responded positively; 30% decrease in tics, 42% decrease in ADHD symptoms – Desipramine statistically better than clonidine for ADHD with comorbid tourettes in children and adolescents; neither exacerbated tics (Singer et al 1995 n = 34) – Desipramine in children & adolescents (Biederman et al 1989, n = 62); 68% responded positively “much or very much” improved Wellbutrin for ADHD Adults – DBPC positive (Wilens et al 2001, n = 40) – BPP v. MPH v. placebo all negative (Kuperman et al 2001, n = 30) Children and Adolescents – DBPC positive (Conners et al 1996, n = 109) – BPP v. MPH both positive (Barrickman et al 1995, n = 15) – BPP for ADHD w/adolescents w/comorbid MDE 62% response rate to ADHD, 85% for MDE; no statistical improvement in ADHD per teachers (Daviss et al 2001, n = 24) Effexor for ADHD Effexor - contradictory open label data in children and adults By example, Motavalli & Abali (2004) demonstrated efficacy in an open label study of 13 children and adolescents (average age = 10 y/o) dosed venlafaxine to an average of 40 mg (+/- 7 mg); Connors parent rating scales and CGI ratings both showed significant improvement Modafinil (Provigil, Sparlon) FDA approved for narcolepsy, EDS associated with sleep apnea, & shift work sleep disorder Variable open label results with higher doses suggested to possibly improve symptoms of ADHD One RDBPC Trial, 189 children (ages 6-17), 7 weeks randomized to modafinil (dosed for weight; <30 kg = 340 mg/d & >30 kg = 425 mg/d) w/2 week blinded withdrawal (no discontinuation syndrome noted) demonstrated statistical separation by week #1 (Effect Size = 0.76) Side Effx = insomnia (24% vs. 1%), H/A (17% vs. 14%), decreased appetite (14% vs. 2%), rare risk of Stevens- Johnson Syndrome Modafinil (2): Provigil, Sparlon A second trial of children ages 7 – 17 with ADHD (9 weeks, double-blind, flexible dose [170 – 425 mg], randomized to once daily drug vs. placebo) Modafinil led to statistically significant reductions in symptoms of ADHD at home and at school Side Effx = insomnia, headache, decreased appetite, and weight loss Published Modafinil Studies To Date A randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled trial of modafinil in children and adolescents with attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder. Kahbazi et al, 2009 Modafinil improves symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder across subtypes in children and adolescents. Biederman et al, 2008 Modafinil as a treatment for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in children and adolescents: a double blind, randomized clinical trial. Amiri et al, 2008 Efficacy and safety of modafinil film-coated tablets in children and adolescents with or without prior stimulant treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: pooled analysis of 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Wigal et al, 2006 A comparison of once-daily and divided doses of modafinil in children with attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled study. Biederman et al, 2006 A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of modafinil film-coated tablets in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Greenhill et al, 2006 Modafinil film-coated tablets in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose study followed by abrupt discontinuation. Swanson et al, 2006 Efficacy and safety of modafinil film-coated tablets in children and adolescents with attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, flexibledose study. Biederman et al, 2005 Vyvanse (lisdexamfetamine) Dextro-Amphetamine – Contrast to Adderall (25% L-Amp & 75% D-Amp) Pro-drug Stimulant (20, 30, 40, 50, 60, & 70 mg dosages) 10-12 hour duration Lower “drug liking effects” among drug abusers than amphetamine (diminishing at higher doses) Once daily dosing; can be dissolved in water Side Effx = as amphetamine Daytrana (The “patch”) Methylphenidate 10-12 hour duration One patch per day worn for 9 hours Dosages: 10 mg (27.5 mg @ 1.1 mg/hour), 15 mg (41.3 mg @ 1.6 mg/hour), 20 mg (55 mg @ 2.2 mg/hour), & 30 mg (82.5 mg @ 3.3 mg/hour) Side Effx = as methylphenidate Texas Medication Algorithm Revised (JAACAP, June 2006) Uncomplicated ADHD: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Stimulant 2nd Stimulant Atomoxetine Bupropion or TCA Alternate (BPA/TCA) Alpha-2 agonist Texas Medication Algorithm Revised (JAACAP, June 2006) ADHD with Depression: 1. 2. 3. 4. Non-medication alternatives If ADHD worse, begin ADHD algorithm If depression worse, begin MDD algorithm If ADHD improves but there is no change in depression, begin MDD algorithm 5. If ADHD or MDD worsens, begin MDD algorithm 6. If MDD improves but ADHD remains unchanged or worsens, begin ADHD Texas Medication Algorithm Revised (JAACAP, June 2006) ADHD with Anxiety: 1. 2. 3. Atomoxetine or Stimulant for ADHD If ADHD symptoms improve but not anxiety, add an SSRI If ADHD symptoms don’t improve or anxiety persists, change to alternate ADHD agent (atomoxetine or stimulant) Texas Medication Algorithm Revised (JAACAP, June 2006) ADHD with Tics: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Begin ADHD algorithm If nonresponse to ADHD treatment, continue with algorithm If ADHD improves but tics persist or worsen, add alpha-2 agonist If tics do not respond, try an atypical antipsychotic If tics do not respond, try haloperidol or pimozide Texas Medication Algorithm Revised (JAACAP, June 2006) ADHD with Aggression: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Begin ADHD algorithm Add behavioral intervention Add atypical antipsychotic to stimulant Add LiCO3 or VPA to stimulant Use alternate agent not tried in Step #4 Other Treatments Focalin (dex-MPH), use at 50% MPH dose Focalin XR Pemoline (Cylert) Methamphetamine (Desoxyn) Reboxetine Atomoxetine HCl (Strattera): Mechanism of Action Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; acts at presynaptic neuron; primary mechanism Significant increase in dopamine noted in PFC No DA increase noted in nucleus accumbens (limbic system) No DA increase noted in striatum Mechanism of Action A Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor (NRI) Relative Monoamine Transporter Affinities Compound NE 5-HT DA Atomoxetine 5 77 1451 MPH 339 >10,000 34 Desipramine 3.8 179 >10,000 Bupropion >10,000 >10,000 562 Imipramine 98 19 >10,000 Fluoxetine 1022 7 4752 Strattera: Pharmacokinetics/ Pharmacodynamics Rapidly absorbed following oral administration Maximal plasma concentrations reached 1–2 hrs p dose Metabolized via hepatic CYP P450 2D6 Half-life (t½) ~ 5 hours (~ 20+ hours in poor metabolizers) Observed duration of action with once-daily dosing suggests: – Therapeutic effects may persist after drug is cleared and/or – Brain concentration may differ from plasma concentration Strattera: Pharmacodynamics Cont’d Brain Concentration 10X Plasma Concentration* Strattera Concentration (ng/mL or ng/g) 3000 Brain Plasma 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 0 5 10 15 Hours** *AUC. **Mouse half-life ~1 hour; (human half-life 5 hours). Data on file, Eli Lilly and Company. 20 25 30 Strattera: Efficacy in Children & Adolescents 24-hour duration of action with once-daily dosing Incidence of insomnia comparable with placebo (for children/adolescents) Not contraindicated in patients with tics and anxiety Nonstimulant/noncontrolled substance May improve some measures of functional outcome (not just core ADHD symptoms) Comparability Relative to Methylphenidate (cont.) Strattera vs. Concerta RDBPC trial of 220 children (6 – 16 y/o), all subtypes, were randomly assigned to 0.8 – 1.8 mg/kg/day of Strattera (n = 222) or 18 – 54 mg/day fo Concerta (n = 220) or placebo (n = 74) for 6 weeks The a priori specified primary analysis compared response (at least 40% decrease in ADHD Rating Scale total score) to Concerta with response to atomoxetine and placebo. After 6 weeks, patients treated with methylphenidate were switched to atomoxetine under double-blind conditions. The response rates for both atomoxetine (45%) and methylphenidate (56%) were markedly superior to that for placebo (24%), but the response to Concerta was superior to that for atomoxetine. Completion rates and discontinuations for adverse events not significantly different from those for placebo. Of the 70 subjects who did not respond to methylphenidate, 30 (43%) subsequently responded to atomoxetine. Likewise, 29 (42%) of the 69 patients who did not respond to atomoxetine had previously responded to Concerta – Newcorn et al, 2007 Relative Efficacy of ADHD Therapies: Effect Size 3 (Swanson et al, 2001) 2 Effect Size Effect size: a statistical measurement of the magnitude of effect of a treatment. Large = 0.8 1 Large (0.8) Moderate (0.5) Small (0.2) 0 –1 Nonstimulant Stimulant Long-acting Stimulant Faraone SV et al. Poster presented at APA; May 17–22, 2003; San Francisco, CA. Swanson JM et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:168–179. Understanding Effect Size (1) What Works Best?…or the Art of Psychopharmacology Effect Size – A measure of the “real” population difference between 2 groups; it measures the effectiveness of the treatment: 0.2 = small; 0.5 = moderate; 0.8 = large Stimulants Effect Size in MTA Study = 1.2; in metaanalysis of 62 stimulant studies = 0.78 (teacher) & 0.54 (parent); average response rate in 155 controlled studies in children/adolescents & adults (Spencer, 1996) = 70% Strattera Effect Size = 0.7 (based on 6 pre-marketing clinical trials in children/adolescents and adults); average response rate in clinical trials = 70% α-2 Agonists Effect Size = 0.4 Understanding Effect Size (2) Strattera: Side Effects Children and Adolescents: – Decreased appetite (15%) – – – – Ave wt loss of 2 – 4 LB in first 3 months, then resume nl growth Dizziness (5%) Dyspepsia (5%) Sedation BP/HR Adults: – Anticholinergic side effects (dry mouth, constipation, urinary – – – – retention) Sexual SEfx (decreased libido, erectile disrurbance, anorgasmia) Insomnia Nausea and decrease in appetite BP/HR Liver Toxicity?...Suicide? Published Studies in Adult ADHD Study Mattes et al Wender et al Gualtieri et al Shekim et al (open label) Spencer et al Iaboni et al Wilens et al Wilens et al Paterson et al Taylor et al Horrigan et al (open label) Spencer et al Taylor et al Michelson et al Year 1984 1985 1985 1990 1995 1996 1996 1999 1999 2000 2000 2001 2001 2001 N 26 37 8 33 23 30 42 35 68 21 24 27 17 536 Medication Duration* Methylphenidate 3 weeks Methylphenidate 2 weeks Methylphenidate 5 days Methylphenidate 8 weeks Methylphenidate 3 weeks Methylphenidate 2 weeks Pemoline 4 weeks Pemoline 4 weeks Dextroamphetamine 4 weeks Amphetamine 2 weeks Amphetamine 16 weeks Amphetamine 3 weeks Amphetamine 2 weeks Strattera 10 weeks *Active Treatment Period Patients in Whom You Might Consider Strattera History of adverse effect to stimulants Comorbid anxiety, depression, tics, enuresis or Tourette’s Require 24 hour symptom relief Severe stimulant rebound Personal or family history of substance abuse Concern about insomnia or appetite suppression Monthly prescriptions are a major hassle Any newly diagnosed patient for whom you determine the treatment to be appropriate Patients in Whom You Might Consider Stimulants History of favorable response to stimulants Those who require “drug holidays” Obese/overweight patients Concern about manic activation Augmenting Strattera When you need a “powerful punch” Any newly diagnosed patient for whom you determine the treatment to be appropriate Organizational Skills Training Manualized Treatment, Flexibly Applied to Individual Needs 20 sessions conducted in 10 weeks Meet with child and parents Consult with teachers Focus on practical routines that children can use over and over again Rewards and reinforcement used to motivate students to change Treatment Areas for Organizational Skills Management Tracking Assignments Organization of Settings Materials Management – Collection – Storage – Transfer Time Management – Time Estimation – Scheduling Planning – Single Time Period – Long-Term Projects – Setting Priorities – Determining Breaks Parent Problems Related to ADHD Parents of children w/ADHD are 3-5x more likely to become separated or divorced Parents of children w/ADHD have a higher incidence of depression & family discord Majority of parents of children w/ADHD report making changes in work status 9 – 35% risk that a parent of a given patient has ADHD