Part Four - Kansas State University College of Architecture, Planning

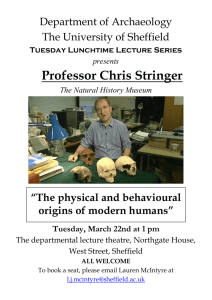

advertisement

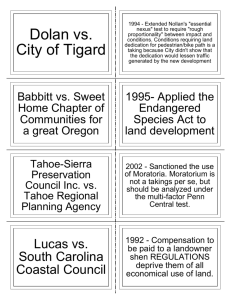

The Taking Issue Lecture Series 3 John Keller – Plan 752 Planning Law “Nor shall private property be taken except for a public purpose and then on payment of just compensation” “The Takings Clause” the 5th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States Introduction to Takings • The First Period – Pre 1856 – The general legal conception is that no taking can occur without a touching – A touching is a physical invasion on to private property by the government Examples of Touching • Brick Presbyterian Church v City of NY – In 1843 NYC passed a law that prohibited “dead bodies from being buried within the city limits” – Brick Presbyterian Church purchased a plot of ground next to the church for cemetery purposes – They brought suit against NYC on the theory that their property had been taken since it could no longer be used for burial purposes Brick Continued • Brick’s Argument – A regulation so severe as to deprive an owner of all p[practical use of the property is a taking and due compensation • Court’s Decision – No reason can be advanced for providing compensation for an injury arising from a mere regulation. No property was entered and none was taken The Wharf Case • Commonwealth v Alger – City of Boston passes a law in 1847 that prohibits the erection of a wharf into the Boston harbor unless it is less than 100 feet. The harbor was nearly impassible by this time because of wharf’s projecting far out into the navigation area Alger - Continued • The Allegation – Alger brings suit under the theory that this constitutes a restraint of free trade and deprives them of the opportunity to use their property to the fullest. Their allegation is that a restraint of trade is the same thing as the government divesting them of all or part of the title to their property Alger - Decision • The Court Finds – This is a just restraint of an injurious use. Government uses eminent domain to appropriate property to a private use and the police power to prevent injury to the public interest. This is not an appropriation of property but a restraint. Second Period • Civil War to Mugler – Judicial thinking remain much the same until after the turn of the Century – In order to find a taking – government must constitute some sort of physical invasion of private property. If government enacted a regulation to protect the public from an injurious use – it was not more than a mere regulation. Pumpelly v Green Bay • A Physical Invasion – In 1871 the U.S. Army Engineers erected a dyke along a one side of a river.to protect a fort from flooding. This caused the adjacent field to flood more often than was normal. Pumpelly sued under the theory that the government had taken his land as a water storage basin The Decision • The Interpretation – The court found that in the strict sense of the law the property was not taken by the government. However, the floodwater, which normally inundated the fort was diverted to the owner’s land and this, in reality constitutes a physical invasion or a touching – and thus a taking that must be compensated Alcohol and Kansas • Mugler v Kansas - 1887 – In 1880 Kansas passed a constitutional amendment that forbade the manufacture of alcohol. Mugler owned a distillery in Salina, KS. In 1885 he was ordered to cease operations. Mugler sued under the theory that the State had deprived him of all value of his land and the $10,000 he had paid for the manufacturing operation Supreme Court Reasoning • The Rationale – The prohibition by the State of Kansas, in its Constitution and laws, of the manufacture or sale within the limits of the State of intoxicating liquors for general use there as a beverage, is fairly adapted to the end of protecting the community against the evils which result from excessive use of ardent spirits; and is not subject to the objection that, under the guise of police regulations, the State is aiming to deprive the citizen of his constitutional rights. Mugler - Continued • The Findings – A prohibition upon the use of property for purposes that are declared by valid legislation to be injurious to the health, morals or safety of the community, is not an appropriation of property for the public benefit, in the sense in which a taking of property by the exercise of the State's power of eminent domain is such a taking or appropriation. – AND Mugler - Continued The destruction of a property right, in the exercise of the police power of the State,in violation of law,is not a taking of property for public use, and does not deprive the owner of it without due process of law. Mugler After the Trial & Mugler’s Granddaughter Today Justice Harlan’s Dictum • The State takes property for the public good and for public use through eminent domain after compensation • The State protects the public health and safety through the police power • No compensation can arise from a mere police power regulation The Modern Era • Penn. Coal Company v Mahon – A Penn statute forbids the removal of the coal support estate under any land used for a residence, cemetery, school, public building, town, or factory – Mahon had purchased the home from an individual who had sold the mineral and supports rights to Penn Coal. Mahon purchased the property with full knowledge that the support right had passed to Penn Coal The Act Centralia 1983 Centralia 1999 Centralia Today - 2002 National Fuel in 1922 Support Estate Justice Holmes • Government could hardly go on if to some extent values incidental to property could not be diminished without paying for every such change. Some values are enjoyed under an implied limitation and must yield to the police power. But obviously,the implied limitation must have its limits or the right of contract and the due process clause are gone Holmes Continues • One fact for consideration in determining such limits is the extent of diminution. When it reaches a certain magnitude, in most if not in all cases, there must be an exercise of eminent domain • The right to coal consists in the right to mine it. This coal is the property of the Penn Coal Company. In this sense all value of the property has been destroyed The Impact • Penn. Coal makes the end of an era of judicial thinking. • The impact is that a “regulatory taking” was possible when the magnitude of the diminution passed a certain point • In the Penn Coal was this magnitude reach the categorical level where all value of the resource was destroyed Agins v Tiburon 1980 • After appellants acquire five acres of unimproved land in Tiburon for residential development • The city was required by California law to prepare a general plan governing land use and the development of open-space land. • In response, the city adopted zoning ordinances that placed appellants' property in a zone in which property may be devoted to one-family dwellings Restrictions • Sliding scale densities allowed between 1 – 5 dwellings on the 5 acre tract • Agins sues for a taking • Claims damages of $2 million and that the ordinance is facially invalid Findinsg • In this case, the zoning ordinance substantially advances legitimate governmental goals. The State of California has determined that the development of local open-space plans will discourage the "premature and unnecessary conversion of open-space land to urban uses." Must Compensation Be in the Same Coin? • Penn. Central Transportation Company Background • The New York City Landmarks Designation Law is administered by the Landmark Review Committee of 11 members with a staff • They are charged with approving any changes or modification to a Landmark Property • Grand Central Station was completed in 1913 by Reed , Stern and Warren and was designated as a landmark site in 1968 Grand Central – A National Masterpiece in the French Beaux Arts Controversy • Penn. Central Railroad gave a 50 year lease to a U.K. Corp. who intended to build a complex of office buildings above the terminal • Two plans were submitted – the first for 55 stories and the other for 53 stories. One plan would have stripped the façade from the building Commissions Review • “A 55 story office building above a flamboyant Beaux-Arts façade cannot be divorced from the setting.” The Landmarks Commission designates a number of other properties owned by Penn. Central as receiving zones Other Buildings By the Architect Taipei 101 in Taiwan The Concept Transfer Rights Scheme • Under the TDR concept, the owner may transfer the development rights from the sending to a designated receiving zone Sending District Receiving Zones Response • Penn. Central files suit alleging that the Landmarks ruling and transfer law constitute a taking is that just compensation was not given to them • Landmarks Commission responds by noting that Penn. Central owns numerous properties in the nearby vicinity suitable to accept this type of density And Further • Penn. Central argues that they are losing money on the operation of the terminal and need to income from the lease to turn a profit. • The Terminal is a valuable property interest, They urge that the Landmarks Law has deprived them of any gainful use of their "air rights" above the Terminal and that, irrespective of the value of the remainder of their parcel, the city has "taken" their right to this superjacent airspace, thus entitling them to "just compensation" measured by the fair market value of these air rights. Supreme Court Decision • Nothing the Commission has said or done suggests an intention to prohibit ay construction above the Terminal. • The Commission's report emphasized that whether any construction would be allowed depended upon whether the proposed addition "would harmonize in scale, material, and character with the terminal.” • Since appellants have not sought approval for the construction of a smaller structure, we do not know that appellants will be denied any use of any portion of the airspace above the Terminal. TDR Ruling • Although appellants and others argue that New York City's transferable development rights program is far from ideal, The New York courts here supportably found that, at least in the case of the Terminal, the rights afforded are valuable. • While these rights may well not have constituted "just compensation" if a "taking" had occurred, the rights nevertheless undoubtedly mitigate whatever financial burdens the law has imposed on appellants and, for that reason, are to be taken into account in considering the impact of regulation. Conclusion • On this record, we conclude that the application of New York City's Landmarks Law has not effected a "taking" of appellants' property. The restrictions imposed are substantially related to the promotion of the general welfare, and not only permit reasonable beneficial use of the landmark site, but also afford appellants opportunities further to enhance not only the Terminal site proper but also other properties. How Big Is A Taking? • Loretto v.Teleprompter Manhattan CATV Corp. The Controversy • Mrs Loretto purchases a 5 story apartment building in NYC • The previous owner of the building granted CATV the right to install TV cable lines and connectors on the outside of the building. The building’s tenants themselves were not connected to the cable And Then • Two years after Mrs. Loretto purchases the building the CTAV runs a line to the tenants in the building • The CTAV did not ask permission • A NYC Law forbade interference by a landlord and just grants them a flat one dollar compensation. Tenants had to pay for the actual cost of hookup The Tenants Were Pleased Mrs Loretto Was Not Pleased • She discovers the installation • Claims a taking and a trespass • The district court rejects the claim that a physical occupation always constitutes a taking Analysis • On appeal the court determined that the law requires that a landlord allow both crossover and non-crossover connection. The owner would be compensated for non-crossover connections only. The court did not determine if $1 was adequate compensation. They said the law was necessary in a era of rapidly growing communications Supreme Court Decision • There is no exact set formula of what constitutes a taking – A taking is more easily found where they is a direct physical invasion rather than a public regulation – Even though the interference is “insubstantial” a physical invasion is still compensable – And the courted noted that there are three distinctions that should be considered Distinctions • A permanent physical invasion • A physical invasion of short duration • And a regulation that merely restricts the use of property Permanent Temporary Regulatory Conclusions • In short, when the "character of the governmental action," is a permanent physical occupation of property, our cases uniformly have found a taking to the extent of the occupation, without regard to whether the action achieves an important public benefit or has only minimum economic impact on the owner Result • Teleprompter's cable installation on appellant's building constitutes a taking under the traditional test. • The installation involved a direct physical attachment of plates, boxes, wires, bolts, and screws to the building • We find no constitutional difference between a crossover and a non-crossover installation. The portions of the installation necessary for both crossovers and noncrossovers permanently appropriate appellant's property. Accordingly, each type of installation is a taking. The Swamp Case Series – Parsippany-Troy Hills The Area Background • This involves the use of a wetlands area of about 1,500 acres know as Troy Meadows • There are practically no uses in this area and about 75% is owned by a private conservation trust • The plaintiff owns and operates a sand and gravel extraction business on a large tract zoned industrial. This company has filled a large portion of their land The Controversy • In 1954 the township passes a zoning amendment that forbids the establishment of any new use, or the expansion of an existing use, in the Troy Meadows except for an agricultural type use. The law also forbade the filling of the wetlands The Actions • Later, a new Meadowlands Development Zone was added that allowed hunting and fishing, communications towers, wildlife parks, and sewage plants and public water facilities Response • The sand and gravel business ignored the new amendments and continued to fill their portion of the wetlands. • Finally the business file suit saying that the government had appropriated the property to public use • They were allowed under a special permit to fill within 300 feet of the road The Case • New Jersey Supreme Court – the two main and practical effect of retaining the meadows in their natural interrelated aspects are: – first, a detention basin in aid of flood control in the lower reaches of the Passaic Valley far beyond this municipality; – and second, preservation of the land as open space for the benefits which would accrue to the local public from an undeveloped use such as that of a nature refuge by the Wildlife Preserve This prime public, rather than private, utilization can be clearly implied from the purpose sections of the zone regulations The Decision • We are in danger of forgetting that a strong public desire to improve is not enough to warrant achieving the desire by a shorter cut than the constitutional way of paying for the change.“ • While the issue of regulation as against taking is always a matter of degree, there can be no question but that the line has been crossed where the purpose and practical effect of the regulation is to appropriate private property for a flood water detention basin or open space. Just v Marinette County 1972 Lake The Just’s Tract – 36.4 acres Noquebay No Fill Area The Statute • Wisconsin passes a shore lands ordinance • Shore lands are defined as land within 1,000 feet of the normal high water elevation of navigable lakes • All county shore land ordinances must be approved by the state or the state will adopt an ordinance for them Now Comes the Justs • The Justs buy a tract of 36 acres along a navigable lakes • It has a frontage of 1266’ along the lake • Over the next few years the Just sell 5 lots with lake frontage that extend back 600 feet – it has a frontage of 366’ The Just’s Land 366 feet Lake 5 parcels sold Noquebay Land retained by the Just’s Marshes and Swamp Land The Next Act • Without a permit the Justs begin filling the marshes with sand and fill dirt • County issues a stop work order and fines the Justs • The Justs file suit in district court alleging that the ordinance constitutes a taking without compensation Legal Test • The trial court finds for the State and fines the Justs • The Justs appeal and demand money damages • The State contends that it is a conflict between the right of the property owner to alter land versus the authority of the State to prevent environmental destruction The Court’s Questions • Is an owner’s right to alter land so absolute that it can be changed to any purpose? • Is this case is an owners right so absolute that they can change the essential character to an use that is unsuitable and damaging to the rights of others? Rulings • This is not a case where an owner is prohibited for using land for natural or indigenous uses • Altering and filling are not always prohibited – just when they pose harm • Nothing in law indicates that destroying a wetland is a reasonable use of the land Final Decision • The Justs say that the value of their land has been severely depreciated • This depreciation is only based on what the land would be worth if it were filled for housing – not its natural state The Justs Were Not Happy and Bought a Portable Sign To Place On Their Property Sibson v State To be Filled Sibson House Wetland 6 acres tract Background • Sibson owns a 6 acre tract of wetland near Portsmouth NH. • The Sibson’s filled 2 acres of the wetland, constructed a house, and later sold it for $75,000 • They then applied to fill the remaining 4 acres The Application • The NH Board of Water Resources denied the permit and cited irreparable harm to the ecology of the marsh. • The Sibson’s claimed a taking and filed suit to force compensation • They relied on the Penn Coal case citing that when all or substantially all of the value of land is taken through regulation that the owner is due just compensation NH Supreme Court • The court found that clearly the police power is sufficient to prevent the filling of the marsh and that the power was properly exercised by the state • “The action of the State Board did not depreciate the value of the wetland. Its value was the same after the denial of the permit. All traditional uses of the wetland remain. In other words, if you pay swamp prices you get swamp uses. The owner has no absolute right to change the essential character of the land for a purpose to which it is unsuited Agins v Tiburon Agins v Tiburon 1980 • California requires all cities to prepare a general land use and open space plan • Agins, a developer, acquires 5 acres in Tiburon. • Tiburon is nearly 100% developed • A new zoning amendment is passed which placed Agin’s land in a district that allowed between 1 – 5 homes – discretionary on review by the city Agin’s Issues • Agin’s claims a regulatory taking in that they could not recoup the value of the land with just one home • Tiburon claims the issue is not ripe because the rule was not tested as applied • Does the amendment deny Agin’s all use of the land without just compensation Supreme Court Decsion • Since no development plan was submitted, the court had to answer the question of a facial taking • A ordinance such as this cannot be a taking as long as the state advances a legitimate interest or denies all economically viable uses of the property • The legitimate state interest in this case is the value of open space and urban conversion First English Angeles Nt. Forest Background • In 1957 the First Evangelical Lutheran Church purchases21acre parcel of land in a canyon along the banks of the Middle Fork of Mill creek in the Angeles National Forest. This land is a natural drainage channel for the watershed area owned by the National Forest service. The Use • A summer camp for handicapped children • July 1977, a forest fire destroys approximately 3,860 acres of the watershed area, creating a serious flood hazard. February 1978 a flood occurs and the runoff from the storm floods the land where Lutherglen sits and destroys all of its buildings. After the Flood Its hard to make something foolproof when there are so many clever fools Enter the County • L. A. County passes an ordinance that forbids building anywhere in the interim flood zone. • If course Lutherglen is right in the middle of the flood zone • And, of course First Lutheran files suit against Los Angeles County Case and Appeals • The district court dismisses the suit for damages by First Lutheran for a taking of there property. • The appeals court upholds the trial court citing Agins v Tiburon. • There is also a snicker or two about L.A. County participating in cloud seeding and causing the whole thing. Cloud Seeding? “Members of our church always wear their seatbelts so aliens can’t suck them out of the car” More Courts • Eight years after the initial hearing the case is passed to the Supreme Court • The question now does not relate to Lutherglen itself, but whether a taking can be characterized as “temporary” • The Sp. Ct. finds that the proper remedy is monetary damages if the ordinance is found to constitute a taking Bottom Line • As Justice Holmes aptly noted more than 50 years ago, "a strong public desire to improve the public condition is not enough to warrant achieving the desire by a shorter cut than the constitutional way of paying for the change • Remand the case to Calif. Courts to determine if a taking occurred Opening Shots - Nollan • The Nollans own a beachfront property in Ventura County California. • ¼ mile north of the property is the Faria County Park (an Oceanside public beach and recreation area). Another public beach known locally as the “Cove” is located approx. 1,800 ft to the south of the property. Facts • An 8’ high sea wall divides the lot from the beach portion of the lot. At the time a 504 sq. ft. bungalow existed on the property and was used to rent out to vacationers Regional Location Closer View Here It IS! Seawall Next Round • Nollans originally leased the lot with the option to buy. Nollans wanted to buy the lot and could do so under the following conditions: • Existing bungalow must be demolished and a single family structure (remaining consistent with neighboring structures) would replace it. – In order to replace structure Nollans needed coastal development permit from the California Coastal Commission. A permit of application was submitted on Feb. 25, 1982. Controversy Begins • Commission recommended permit upon the condition that they allow a public easement on the portion of their property bordered on one side by the 8ft sea wall and on the other by the mean high tide line. Essentially allowing a lateral easement for the public to pass through their property. • Nollans protested the condition but the California Coastal Commission overruled and granted the permit pending the Nollans obtain recordation of a deed restriction granting the easement The Arguments • Nollan’s Argument • Condition could not be imposed unless the proposed development had a direct adverse impact on the public access to the beach • The California Coastal Commission condition was essentially a taking and in violation of the property clauses in the Constitutions 5th and 14th Amendments The Contra Arguments • California Coastal Commissions Argument • Protecting the Public’s ability to see the beach • Assisting the public in overcoming the “psychological barrier” to using the beach created by a developed shorefront • Preventing congestion on public beaches • Commission had similar conditions on 43 of the 60 properties in that tract The Court History • Court History • June 3, 1982-Nollans appeal to the Ventura California Superior Court to invalidate the access condition. Court agrees and sends case back to California Coastal Commission. • California Coastal Commission holds public hearing and reaffirms its position on the condition. • Nollans take case to Superior Court claiming the condition is in violation of the taking clause of the 5th Amendment. Court sides with Nollans. Next Step • California Coastal Commission appeals to the California Court of Appeals. Court of appeals finds in favor of the California Coastal Commission citing that if the project creates a need for public access and condition was related to burdens created by the project the condition would be constitutional. • Case is taken to U.S. Supreme Court and argued March 30, 1987. Enter the Supreme Court • U.S. Supreme Court Decision and Implications • Court found that a “permit condition is not a taking if it serves the same legitimate governmental purpose that a refusal to issue the permit would serve” (Mandelker 2003). • However, it is unclear how allowing a lateral access will lower the “psychological barrier” imposed by the new development and or how it helps to alleviate congestion in the two near by public beaches. It is further unclear as to how the access will help reduce the viewing of the public beach. Conclusions • In a sense there was not found to be a “nexus” between the California Coastal Commissions arguments and the intended purpose of the condition. • Court agrees with the commission that the comprehensive coastal access proposed by the California Coastal Commission is a good idea, however they will have to compensate the Nollans if they want the easement. • Court finds in favor of the Nollans. In Other Words • There was a touching (permit condition) • The State could not raise the need to such a level that it would justify a physical interference with the Nollan’s property David H. Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council U.S. Supreme Court 505 U.S. 1003 June 29, 1992 Background • 1972: Federal Coastal Zone Management Act • 1977: South Carolina Coastal Zone Management Act – Based on federal Act to require permits to be obtained before development in “critical areas” along beachfronts • Late 70’s: Lucas and others developed Isle of Palms • 1986: Lucas purchased two lots in Beachwood East Subdivision for $975,000 • 1988: Beachfront Management Act – Construction of habitable improvements was prohibited seaward of a line drawn 20 ft. landward and parallel to the baseline. Background Context Lucas v Carolina Coastal Commission Merrick Road Beach Line 1986 Beach Line 1956 Beach Line 1902 Lot 2 Lot 1 Controversy • Lucas bought two beachfront lots zoned for single-family residential development in 1986 with no restrictions imposed upon the use of the property by the state, county, or town • In 1988, the Beachfront Management Act made a permanent ban on construction on Lucas’s lots Trial Court • Lucas contends that the construction of the Beachfront Management Act caused a taking of his property without just compensation • The Trial Court agreed and found that the Act “deprived Lucas of any reasonable economic use of the lots,…eliminated the unrestricted right of use, and rendered them valueless” Change in Beachfront Management Act • In 1990, while the issue was in front of the South Carolina Supreme Court and before issuance of the court’s opinion, the Act was amended to allow for special permits to be issued • The State Supreme Court determined that that case was unripe Supreme Court of South Carolina • The State Supreme Court reversed the decision • The court’s reasoning was that “when a regulation respecting the use of property is designed to prevent serious public harm, no compensation is owing under the Takings Clause regardless of the regulation’s effect on the property’s value” Dissent of State Supreme Court • Two justices dissented because “they would not have characterized the Beachfront Management Act’s primary purpose as the prevention of a nuisance” • “To the dissenters, the chief purposes of the legislation, among them the promotion of tourism and the creation of a habitat for indigenous flora and fauna, could not fairly be compared to nuisance abatement” US Supreme Court • Prior decision was overturned based on two principles: – The court decided that the case was ripe because it was filed before the amendment to the Act in 1990 – The State Supreme Court erred in applying the noxious uses principle • Tie in to previous case law – In Pennsylvania Coal v. Mahon, 260 U.S. 413, “if the protection against physical appropriations of private property was to be meaningfully enforced, the government’s power to redefine the range of interests included in the ownership of property was necessarily constrained by constitutional limits” Reasoning • Lucas sacrificed all economically beneficial uses in the name of common good, so it is a categorical taking • Creating a distinction between regulation that prevents “harmful uses” and that which “confers benefits” is next to impossible • Background principles of nuisance and property law must be defined After The Case After the case was reversed and remanded to the trial court in South Carolina, both parties wisely agreed to settle rather than expose themselves to the whims of a jury. The settlement amounted to $1.575 million. Lucas got his investment back, was able to pay off his lawyers and pocketed $100,000 for his 4 years of trouble. He also agreed to convey title to the state. So what did the state do with the property? With the Beachfront Management Act now amended, the Coastal Council was empowered to issue a special permit allowing the state to sell Lucas' property to developers! The attorney representing the state explained lamely that it needed to recoup some of the monies paid in the settlement. And the state may as well have done so since the two lots have been described as standing out like missing teeth in a row of million-dollar homes fronting the Atlantic Ocean Guess What’s on the Lot Now? The Widow Mrs. Dolan The Place The Ditch The Background • Dolan v Tigard – Mrs Dolan applies to redevelop her site – Plans to expand from 9,700 sq. ft. to 17,600 sq. ft and to pave a 39 space car parking lot – This is in the form of an additional building to the Northeast and a new parking lot Main Street Gravel Parking Lot Fanno Creek Existing Plumbing and Electrical Supply Store The City • After a comprehensive study the City adopted and plan to enhance the drainage of the town and to relieve congestion in the main part of town by connecting new bike paths • The City requires that new development in the CBD dedicate space for the new bike/walkway and also contribute to the drainage system (and also enhance the appearance of Fanno Creek and as greenway system) The Exaction The Commission required that Dolan dedicate the portion of her property lying within the 100 year floodplain for improvement of a storm drainage system along Fanno Creek and that she dedicate an additional 15 foot strip of land adjacent to the floodplain as a pedestrian/bicycle pathway. The dedication required by that condition encompasses approximately 7,000 square feet, or roughly 10% of the property. In accordance with city practice, petitioner could rely on the dedicated property to meet the 15% open space and landscaping requirement mandated by the city's zoning scheme. Mrs Dolan Replies • Dolan appealed to the Land Use Board of Appeals (LUBA) on the ground that the city's dedication requirements were not related to the proposed development, and, therefore, those requirements constituted an uncompensated taking of their property under the Fifth Amendment. In evaluating the federal taking claim, LUBA assumed that the city's findings about the impacts of the proposed development were supported by substantial evidence. Supreme Court Findings • Without question, had the city simply required petitioner to dedicate a strip of land along Fanno Creek for public use, rather than conditioning the grant of her permit to redevelop her property on such a dedication, a taking would have occurred. • Petitioner does not quarrel with the city's authority to exact some forms of dedication as a condition for the grant of a building permit. • She argues that the city has identified no special benefits conferred on her, and has not identified any special quantifiable burdens created by her new store that would justify the particular dedications required from her which are not required from the public at large. Nexus – The Two Tests • Undoubtedly, the prevention of flooding along Fanno Creek and the reduction of traffic congestion in the Central Business District qualify as the type of legitimate public purposes we have upheld • It seems equally obvious that a nexus exists between preventing flooding along Fanno Creek and limiting development within the creek's 100year floodplain. Petitioner proposes to double the size of her retail store and to pave her new gravel parking lot, thereby expanding the impervious surface on the property and increasing the amount of storm water runoff into Fanno Creek. So – Is the Exaction Fair? • The second part of our analysis requires us to determine whether the degree of the exactions demanded by the city's permit conditions bear the required relationship to the projected impact of petitioner's proposed development. • We conclude that the findings upon which the city relies do not show the required reasonable relationship between the required floodplain and the petitioner’s new building. The same may be said for the need for the bike path Bottom Line • Government must be able to demonstrate a rough proportionality between the need for the exaction and the impact of development Battle Ground WA City of Battleground v Benchmark Land Devel. • As a condition of development approval, the City of Battleground required Benchmark Land Company to improve an existing street adjacent to Benchmark’s proposed subdivision. The street is congested. • The City based its condition upon a generally applicable ordinance requiring developers to construct half-width road improvements to adjoining access streets as a prerequisite to permit approval. Half Street Improvement The Contention Benchmark challenged the condition with and sought damages from the City for a taking. The trial court ruled that studies conclusively showed that there was no substantial impact from the new subdivision on traffic that would warrant the new half street improvement More Studies • After the trial both Benchmark and the City conduct traffic studies. • Guess what – Benchmark’s expert says no impact and the City’s expert says that there will be impact. • Also, the City says that it does not have to do a specific Dolan study ever time that have to improve a new half street Wash. Sp. Ct. 4 Part Test • What must the government establish – A Public Problem – A development that impacts the public problem – Governmental approval of a set of conditions that tends to alleviate the problem – Rough proportionality between the conditions and the solution to the problem The Court’s Analysis • A Dolan style analysis is required when the developer is likely to incur “significant costs” arising from improvements • Battleground fails the essential nexus test – the proposed solution does not tend to alleviate the public problem A Little Salt Marsh Palazzolo v Rhode Island SGI Tract 18 acres 2 acres Upland Beach 16 acres Salt Marsh Shoreline Site Picture Credits to Dan Mandelker for this picture Location Background • Palazzolo v Rhode Island – Palazzolo and associated formed Shore Gardens Enterprises in 1959 for $8,000 – Within a year Palazzolo bought out his associates and became sole owner – For six years Palazzolo filed various applications to fill 11 acres of the salt marsh and all were rejected – After 1966 no further applications were filed for over a decade Into The 1970s • In 1971 Rhode Island creates the Coastal Management Council • The Council adopts rules that severely restrict the filling of salt marshes • In 1983 Palazzolo files an application to fill the entire marsh area and construct a seawall bulkhead. The application is denied. • In 1985 he files an application to fill 11 of the 18 acres of salt marsh for a 75 unit subdivision – this is denied in that it did not meet the standards for a special exception The 1985 Application SGI Tract 18 acres 2 acres Upland Beach Here 11 acres Salt Marsh The Legal Challenge • Palazzolo files suit in state court alleging that the Coastal Management Council deprived him of all economic value of his property • He seeks $3,150,000 in damages • The trial court and the State Supreme Court deny him any relief for several reasons – His claim was not ripe – He took title with full knowledge of the regulations – He still retained about $200,000 in value in the upland parcel Summary Brief Questions Question 1 • Whether the Supreme Court of Rhode Island permissibly treated petitioner's takings claim as unripe, where that takings claim was based on the State's purported refusal to allow large-scale residential development on petitioner's property and petitioner had never sought permission from the appropriate state officials to construct residences Summary Brief Questions 2 • Whether petitioner can establish a taking of property through proof that his land would dramatically increase in value if longstanding development restrictions were removed, even though the restrictions were in effect at the time petitioner acquired the property and the land retains substantial value notwithstanding the restrictions The Supreme Court Decision – The Ripeness Claim • A landowner may not establish a taking before the land-use authority has the opportunity, using its own reasonable procedures, to decide and explain the reach of a challenged regulation • Once it becomes clear that the permissible uses of the property are known to a reasonable degree of certainty, a takings claim is likely to have ripened. Here, the Council’s decisions make plain that it interpreted its regulations to bar petitioner from engaging in any filling or development on the wetlands. Further permit applications were not necessary to establish this point. The Remaining Value • The State Supreme Court did not err in finding that petitioner failed to establish a deprivation of all economic use • It is undisputed that his parcel retains significant development value • Petitioner is correct that, assuming a taking is otherwise established, a State may not evade the duty to compensate on the premise that the landowner is left with a token interest. • This is not the situation in this case, however. A regulation permitting a landowner to build a substantial residence on a parcel does not leave the property “economically idle.” He Figures Out How To Use His Property Tahoe-Sierra Preservation v Tahoe Regional Planning OCTOBER 2001 Lake Tahoe Region Background • Tahoe is the highest – largest alpine lake in the U.S. 22 X 12 miles • Maximum depth 1,645’ • Water purity at 99 percent in1960 • Permanent residents 34,000 with 38,000 temporary residents in seasons Factoids • Considered a national treasure only two lakes in the world are comparable – Glacier Lake and Lake Baikal in Russia • World class amenity value • Tahoe began its environmental deterioration about 40 years ago • Significant increase in the lack of clarity because of algae growth The Big Conclusion • Unless the rate of runoff from impervious cover is reduced or eliminated the great “blue lake” will go green from lack of clarity within this decade and cannot recover under any know natural process Early Efforts • In the 1960s and 70s Nevada, California, seven different counties, 11 municipalities, and the Federal government sign a compact to protect the drainage basin of Lake Tahoe • Restrictions on development are significant but the problem increases • Land owners who purchased lots before 1972 could build at a later time as long as they observed reasonable construction regulations Many Landowners Express Their Disappointment Problems Continued • By 1982 it was obvious that Lake Tahoe was losing ground and that development would have to cease • Stringent regulations were them placed on property according to the potential for harm if the vacant land was developed • Thus, the two moratoria were adopted starting in 1983. In addition to the 32 months, the real delay lasted about 6 years before people could building again So, The Planners Act • Lake Tahoe Regional Planning Association imposes two moratoria on development in order to prepare a revised comprehensive plan and devise strategies for sound environmental growth • This totals 32 months • Sierra-Tahoe Preservation Association claims a temporary taking during the 32 months District Court • Hearing court says that a “partial taking” did not occur under a Penn. Central Analysis. • BUT, a categorical taking did occur during the 32 months under the moratorium because of the Lucas analysis – owners were temporarily deprived of all value for the 32 months Finally, The Supreme Court • As already noted the Supreme Court refused to declare the moratorium a per se categorical taking. It will depend on the moves and counter moves of the parties and a “Penn. Central Style Analysis” will be used • The lot owners are going to be ticked off because they wanted a “fairness and justice” analysis like Del Monte Dunes Observations Some Good Things to Say • It appears that moratoria are essential planning tools to protect the public at large • Moratoria a not that much different than other delays caused by normal administrative review • Moratoria prevent hastily enacted regulations • Moratoria foster informed decision making and per se taking rules do not Repeating The Big Picture • Flexible analysis of regulation takings is required – Penn Central becomes the touchstone case for takings • Moratoria may be categorical takings when they are in force but not all categorical takings are compensable. The Penn Central Analysis • To characterize a governmental action as a taking, the court must – Examine the character of the action – Extent of interference with an investment backed expectation – Diminution and value alone cannot not establish a taking – Extent to which the state can show a compelling interest for the regulation Wild Rice River v City of Fargo 2005 Basic Facts Land is purchased in 1947 Platted in 1993 to 38 lots Sixteen lots located on a Oxbow of Rice River 1994 provides water and service with 10 year agreement with Fargo to provide services Spends 500,000 in initial development costs Sold first lot in 1994 to Rutten for $24,000 And Then ….. Fargo Round One The Aftermath 1997 – All undeveloped lots are flooded and Rutten’s house ruined 1998 – FEMA issues preliminary flood rate map and this shows several lots in the floodway Fargo enacts MORATORIUM for the time necessary for FEMA to issue final map It actually runs for 21 months 1999 – Rutten’s daughter applies for building permit and is denied as are other applicants The Suit 2000 Wild Rice sues Fargo Claims inverse condemnation Tortuous interference with contract In late 2000 Fargo ends moratorium Wild Rice sells several lot is 2002 And 2005 for $39 - $59,000 The trail court dismisses all claims for inverse condemnation, interference and bad faith delay. Also denies a temporary takings claim under the First Lutheran Church theory. Sp. Ct. of ND Appeals The court reviews a large cross section of takings cases including Penn Central and the Lake Tahoe cases Concludes that: The moratorium was system wide and did not single out Wild Rice Fargo was doing was it was required to do – preventing an injury There was no extraordinary delay in government decision making – no bad faith There was no taking – the land was worth more after the moratorium than before City of Glenn Heights Texas v Sheffield Development Co. 2001 Glenn Heights TX Facts • 20 miles south of Dallas •Population of 7,000 in 2008 • 10,470 persons estimated in 2010 •“Glenn Heights is a pleasant residential community with low cost of living just minutes from Dallas. Ideal for those who want the quiet life with the amenities of a nearby metropolitan area.” Website Time Periods of the Case • Prior to the agreement – Involves 194 acres of a 240 acre tract zoned PD 10 – PD 10 was granted in 1988 for single family residence on 6,500 sq. ft lots; some larger lots were included in later phases – Phase 1 of PD 10 (43 acres) has already been fully developed under this concept However • In 1995 Glen Heights adopts a new code • 14 of the existing PDs were not rezoned and they were allowed to continue unchanged. This included PD 10. Due Diligence Phase • Sheffield conducts a due diligence • They concluded that the zoning was secure. • Sheffield purchased the property in 1996 The Moratorium • Glenn Heights enacts a moratorium on the approval of development applications • If Sheffield (et al) were allowed to file an application he would lock in his development rights • Moratorium is to run for 30 days How Many Days • The moratorium should have lapsed in March of 1997 • Sheffield tries to file a final plan • Staff says NO because the city manager extended the moratorium • The City Council officially extends the moratorium until April 27, 1998 To Finish It Off • On the day the moratorium lapses the City Council down zones the remaining 194 acres to 10,000 sq. ft – a loss of 4,400 sq. ft per lot • Sheffield is torqued Temper - Temper Sheffield Goes to District Court • Sheffield files suit for a taking and requests compensatory damages • The district court finds for Sheffield and the jury awards damages $485,000 a reduction from $970,000 • Finds that the down zoning but not the moratorium constituted a taking Sheffield and Glenn Heights Both Appeal to Texas Sp. Ct • Sheffield says yes it was a taking and the district court should have found that the moratorium was also a taking • Glenn Heights says “no way” is this down zoning a taking and we only reduced the property by 38% $289,920 Texas Sp. Ct. Begins Their Anlaysis • Uses a very traditional takings analysis – Two types of taking – physical and regulatory – Courts should not act as a “super zoning board” but give discretion to the legislature – If Glenn Heights advances a legitimate state interest then the down zoning is not a taking The Court Partially Saves Glenn Heights’ Butte • What is the legitimate state interest? – Glen Heights did not make any findings of fact – The trial court really did not address several important issues – However, the testimony at the trial says the down zoning was beneficial because of less density (less crowing, urbanization, less traffic, more open space) – The number of DU’s was reduced from 1,030 to 521 and pop from 3,000 to 1,500 So, That’s One For the City • Reducing population density is a legitimate state interest The Planning Staff Dons Toga and Has An Orgy of Celebrations However, Let Just Hold On For a Minute • Sheffield still has substantial value in the land after the down zoning so it cannot be a Lucas style taking (categorical) of all economic value • But, did the City unreasonably interfere with Sheffield’s investment back expectations and property rights Analysis • If you only had a small brain in their head you knew that Sheffield intended to develop the property at the same density for which it was originally zoned • Even the trial court found that the utilities were properly sized to permit 4 – 5 units per acre – everything in the completed Phase 1 points to the same development patterns in the following units Comes Now the Evil of Density The Court Ponders • When Sheffield undertook their due diligence no one ever mentioned anything about down zoning • Is there a bigger picture here that we are missing? The Contesta DeUrninationa Begins • Sheffield – There is no demand for large lots • City – Bull, you just want every ounce of density you can get. You are just in business to make money • Sheffield – our appraiser says that we have a 90% loss • City – no way, its more like 35% The Court Puts a Stop to the Argument • The City’s argument is weak • There is plenty of good infrastructure to handle this density • The City blind-sided Sheffield. They could have let them know that the rezoning was being considered But Wait – Is the Moratorium a Taking Also • A moratorium , like a down zoning, must advance a legitimate state interest – City Council admits it had a meeting in secret – Admits that they passed the moratorium to increase their bargaining power – Admits that Council discussed the actual rezoning of the property Reverses The Trial Court • The moratorium was improperly used • In this case it constitutes a taking as an unreasonable interference with an investment backed expectation • Awards Sheffield $280,000 damages for the period of the temporary taking Now Its Sheffield Turn Ripening - Introduction Inset Williamson Reg. Plng/Hamilton National Bank Regional Context NASHVILLE Zoning & UGB Case Location Franklin – Williamson County Nashville TN 1985 • In 1973 a developer obtained preliminary permission to develop his tract under a set of “cluster” provisions • The zoning was changed in 1977 under a down zoning scheme • The developer was allowed to continue with the original zoning provisions • In 1979 the developer applied for a final plat on a new phase of his development • The Planning Commission applied the 1977 rules and denied his application A Takings Claim • The developer claim a right to the 1973 regulations • The District court ruled that the developer was entitled to the 1973 density regulations • But, not taking occurred for the temporary deprivation of the economic use of his/her property • The Appeals Court reverse saying that the permit denial did constitute a taking and was entitled to monetary relief The Supreme Court • The Supreme Court reversed the Appeals Ct. • Court notes that the developer did not seek any variances or even apply for variances that would have allowed full development of the property • The claim was not ripe • The developer did not exhaust available administrative remedies • The developer offered not proof that there was substantial interference with investment back expectations Diminution of Land Value Range of Speculative Value Range of police power regulation Resort Hotel Mall Wal-Mart Large Housing Development $2.5 million $1 million $500,000 1 du/acre $40,000 Compelling government reasons Agri Use Only $10,000 Limit of taking immunity Natural Resource Use Only $1,000 Taking – Basic Tests • • • • Touching – Invasion Size is not an issue Creating a Nexus Roughly proportionate to the impact of development • Investment backed expectation • Categorical taking • I smell a rat Triggering Points • Does the regulation or action result in a temporary or permanent invasion of private property? • Does the regulation or action require the owner to dedicate a portion of their property to public use? Roughly Proportional!!!!! • Does the regulation deprive the owner of all or nearly all economic viability? • Does it appear the government is jerking the land owner’s chain? Taking Matrix Agins Style Taking _Rationally Related Nollan/Dolan Style Taking _Exaction Related Taking/Roughly Proportionate Lucas Style Taking Categorical Penn Central Style Taking_Reasonably Necessary to Effectuate a Substantial Public Purpose & Investment Backed Expectations When Its All Over Lingle v Chevron 2005 Hawaii passes law regulating amount that energy company can charge a gasoline dealer for rent Lower court relies on Agins and rules against the state in that the statutes does not “substantially advance a legitimate governmental interest The case reaches the Supreme Court after Hawaii appeals the decision The Supreme Court rejects the Agins’ test as “imprecise” “The “substantially advances” inquiry reveals nothing about the magnitude or character of the burden a particular regulation imposes upon private property rights” Do You sometimes feel like this?