LN Wk 5-1: Lec 2

advertisement

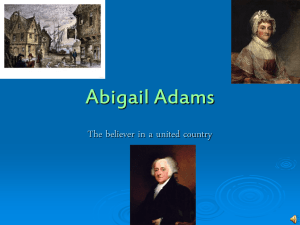

DECLARATIONS IN DIALOGUE: VOICES FROM OUTSIDE Abigail Adams’ letters, 1771-76 The Haitian Declaration of Independence, 1804 TWO CASE STUDIES • In the (north) American colonies, a husband and wife exchange views through letters about who shall be included in the new government to be created by a “Declaration of Independency” • After years of war, Jean-Jacques Dessalines drives out the French and declares the independence of Haiti • What are the rhetorical strategies of two writers who make cases against their exclusion from the central promise of the Enlightenment? • Does either of these cases reimagine key elements of the Declaration’s promise: contract between citizens, equality, rights? “All men are created equal” A gender and color-neutral noun? MEN = males and females? MEN = people of all color and standing? CITIZEN = unmarked? ENLIGHTENMENT PERSPECTIVES ON WOMEN IN THE POLITICAL ORDER Women disqualified from the political participation in most Enlightenment thought on the basis of sex (confinement to reproductive roles) or gender (lacking in qualities of rationality, discipline, strength of character, intelligence) •Women’s weakness disqualifies them from “the distant chase, from war, from the usual subjects of debate” (Condorcet qtd. in Kerber) •Rousseau, Emile: women’s empire: “of softness, of address, of complacency; her commands are caresses; her menaces are tears” BUT . . . •Locke: “Conjugal Society is made by a voluntary Compact between Man and Woman ” (62-65). L. entertained the idea of divorce ECONOMIC BARRIERS TO PARTICIPATION • Coverture: common law tradition (from England) Blackstone, Commentary on the Common Law (1765): “By marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law: that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage, or at least is incorporated and consolidated into that of the husband; under whose wing, protection, and cover, she performs every thing” ABIGAIL ADAMS, 1744-1818 • No formal education; father a Congregationalist minister; taught reading, writing, and numbers by her mother; access to her father’s library of English and French literature • Married to John Adams in 1764 • Lived in Braintree, Massachusetts; bore 6 children • Second First Lady: 1797-1801 Portrait by Benjamin Blythe, 1766 An 18th-century middle-class white woman’s sphere Adams’ house in Braintree, Massachusetts “The Good House-wife,” Colonial Williamsburg Collection What terms best describe Abigail Adams’ ethos? • A. She writes as a citizen to another citizen, making strong arguments for women’s inclusion in the new republic. • B. She writes as a loving wife to her husband. • C. She’s playful and taunting, using humor to persuade. • D. None of the above. • E. All of the above. THE GENRE OF THE LETTER: PUBLIC OR PRIVATE? • Cicero (1st-century B.C.E.); Elizabeth (16th century) • The characteristic genre of the 18th century: “outpourings of the heart” but also a vehicle for political communication • “Private” but not secret: oriented toward an audience; the epistolary novel (Richardson, Pamela, 1740) • An available means for someone excluded from public spaces and official bodies Abigail’s letters • To Isaac Smith (4/20/1771): using the letter for intellectual exchange, overcoming gender and geographical limitations: the “humble cottage” in Braintree: “in immagination place you by me that I may ask you ten thousand Questions” (235) • To John (3/31/1776): “Remember the Ladies” -- ironic use of the language of rights • • restriction on “unlimited power” • “all Men would be tyrants” • we will “foment a Rebelion” • no law without representation John’s reply (4/14/1776): picks up Abigail’s mocking tone • “I cannot but laugh” • Women: “another Tribe” • “We know better than to repeal our Masculine systems” • “Despotism of the peticoat” Abigail’s letters (cont.) To Mercy Otis Warren (4/27/1776): political action • Proposal of a petition • Given the “natural propensity in Humane Nature to domination,” there should be laws in our favor based on “just and Liberal principals” • Abigail has been making a trial of “the Disintresstedness of his Virtue” Abigail to John (5/26/1776): “we have it in our power not only to free ourselves but to subdue our Masters” John Adams’ reflections, May 26, 1776 To James Stewart, not a response to Abigail; moral foundations: “in theory” • “Whence arises the right of the men to govern the women, without their consent? Whence the right of the old to bind the young, without theirs? • A series of questions: “why exclude women?” gender argument: their delicacy reproductive obligations: domestic cares coverture problem: influence of men in control of property • Again, “for what reason”? Reasoning proves “you aught to admit women and children” • Response to his own questions: fear of the multitude: “ “Depend upon it, Sir, it is dangerous to open so fruitful a source of controversy and altercation as would be opened by attempting to alter the qualifications of voters; there will be no end of it.” John to Abigail, July 2, 1776: public deliberation and consensus on nation-formation set aside the question of women’s inclusion “Time has been given for the whole People, maturely to consider the great Question of Independence and to ripen their judgments, dissipate their Fears, and allure their Hopes, by discussing it in News Papers and Pamphletts, by debating it, in Assemblies ,Conventions, Committees of Safety and Inspection, in Town and County Meetings, as well as in private Conversations, so that the whole People in every Colony of the 13, have now adopted it, as their own Act. —This will cement the Union, and avoid those Heats and perhaps Convulsions which might have been occasioned, by such a Declaration Six Months ago.” Adams Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society SOME CONCLUSIONS • Genre: A. Adams uses the the letter to create a kind of public for the purposes of testing and critiquing Enlightenment ideas. She addresses her husband more as a policy-maker than as an intimate: testing his “disinterestedness.” • The letter, with its context of intimacy, allows for a style different from the high seriousness of “rational-critical” debate. Those excluded from positions of power may adopt alternative styles strategically when high seriousness or direct challenge may not be effective. A Declaration of unanimity, an assertion of “one people,” covers over exclusions and silences dissenting voices. “Man” and “citizen” are gender-specific in the Declaration. The attempt to redeem the Enlightenment promise of equality using the category of the rational, disinterested (unmarked) citizen fail in this case. THE COLONY OF SAINT DOMINGUE Beard, J. R. (John Relly) (1863). Toussaint L'Ouverture: A Biography and Autobiography. Chapel Hill, NC: Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH. Online Publication CIRCULATION: OF BODIES, IDEAS, DISCOURSE 16th-17thC: the rise of “racial slavery” – the slavery of Africans and people of African descent The enslavement of non-Europeans to labor in colonies supported the economic system of the West, “paradoxically facilitating the global spread of the very Enlightenment ideals that were in such fundamental contradiction to it” (Buck-Morss 21). Terminology: “black” linked with slave status and used in a discourse of “race” difference; “race” as a discourse, not a biological category COLONIAL SLAVERY: LAW AND ECONOMY • Le Code Noir, French legal code regulating treatment of black slaves in the colonies, 1685: legalized slavery, humans as property, allowed for physical torture and killing of slaves; regulations prohibiting assembly; some protections for marriage, family, and children • “The fortunes created at Bordeaux, at Nantes, by the slave-trade, gave to the bourgeoisie that pride which needed liberty and contributed to human emancipation” (Jaurès qtd. in James, Black Jacobins 47). • October, 1789: Appeal to the National Assembly by mulattoes of San Domingue to be seated as representatives of the West Indies; supported by the Amis des Noirs (anti-slavery); petitions denied. • August 1791: insurrection on Saint-Domingue • February 4, 1794: French National Convention outlaws slavery in all French colonies: citizenship to men of any color Enlightenment thinkers on “race”/color • Immanuel Kant, 1764: “The difference between the two races is thus a substantial one: it appears to be just as great in respect to the faculties of the mind as in color” (from “Observations of the Feeling of the Beautiful and the Sublime”) • David Hume, 1748: “I am apt to suspect the Negroes, and in general all other species of men to be naturally inferior to the whites . . . No ingenious manufactures among them, no arts, no sciences”; a natural distinction (Essays: Moral, Political and Literary”) • Counterarguments from Francis Hutcheson, Montesquieu, Condorcet; Society of the Friends of Blacks (Amis des Noirs) founded in Paris, 1788 CONTRADICTION BETWEEN BEING PROPERTY AND BEING HUMAN • 1776 American Declaration: “unalienable rights”: alienation, the capacity to be separated from, to give or sell away • July 14, 1789: storming of the Bastille Prison, beginning of the French Revolution • August, 1789: Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen • 1. Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good. • 2. The rights of man: liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression. Toussaint L’Ouverture: Letter to the Directory, November 1797 Declaration, against the reinstitution of slavery: • •“the attempts on that liberty which the colonists propose are all the more to be feared because it is with the veil of patriotism that they cover their detestable plans.” • •“It is for you, Citizens Directors, to turn from over our heads the storm which the eternal enemies of our liberty are preparing in the shades of silence. It is for you to enlighten the legislature; it is for you to prevent the enemies of the present system from spreading themselves on our unfortunate shores to suly it with new crimes. Do not allow our brothers, our friends, to be sacrificed to men who wish to reign over the ruins of the human species.” • •“Do they think that men who have been able to enjoy the blessing of liberty will calmly see it snatched away? • •“if . . . this was done, then I declare to you it would be to attempt the impossible: we have known how to face dangers to obtain our liberty, we shall know how to brave death to maintain it.” HAITIAN CONSTITUTION OF 1801 Freedoms: •Abolition of slavery (Article 3) •“Men” not divided legally by color (Article 5) •Individual freedom, safety, and property are guaranteed (Title V): each person owns himself Restraints: •Catholic religion is established; no divorce (Title IV) •Colonists must labor in agriculture; workers as family led by the father (Title VI) •Toussaint L’ouverture, governor for life (Title VIII) •Attachment to French government •Governor as censor (Article 39); right of petition but not assembly (Articles 66 -67) Napoleon’s attempt to reintroduce slavery in SanDomingue, 1801 • 1803: Toussaint L’Overture arrested, imprisoned in France where he died • May 1803, Dessalines in charge; uniting officers from various indigenous forces • Creates a new flag by tearing out the white panel from the French tricolor • Defeats the French; commissions and delivers the Haitian Declaration of Independence 1 January 1804 Haitian Flag, 1806 (L’Union Fait la Force) The Haitian Declaration of Independence, 1804 – Jean-Jacque Dessalines • Commissioned and delivered by Dessalines: “Commander in Chief to the People of Haiti” – renaming the country • Addressed to “Citizens, my countrymen” – soldiers (¶3), to “native citizens, men, women, girls, and children” (¶6), “intrepid generals” (¶8) • Growth out of tutelage: Let us be “by ourselves and for ourselves” (¶9) • At the end of the war with France: an act of “national authority” to assure liberty (¶1): renunciation of the French – a call for vengeance (¶8), eternal hatred (¶13) • Resist French armies and eloquence (¶5): “they are not our brothers”; tigers, vultures (¶6-7) • 1805 Constitution unites Haitians equally before the law, bans any white man from setting foot in the country as land or property owner, and declares Haiti a “black” nation “The Oath which must unite us”; international relations • “Vow before me to live free and independent” (¶17) • Compare with the American Declaration: “And for the support of this declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes and our sacred honor” (final sentence) -----------------------“Swear, finally, to pursue forever the traitors and enemies of your independence” (¶17) – retributive justice with relation to France, but “let us allow our neighbors to breathe in peace . . . Let us not, as revolutionary firebrands, declare ourselves the lawgivers of the Caribbean” (¶11) Cf. American Declaration: “our British brethren”: “enemies in war, in peace friends” CHANGING TERMS? • Social contract between citizens: assumes “unalienated” selfhood as a starting point; assumes unstated or suppressed social conditions (male, European, unindentured, etc.); framed within the language of the bourgeois public sphere (critical/rational) • The human free from bondage as an alternative to the unmarked citizen; specification of different kinds of people under varied circumstances (gender, skin color, geographic location, property ownership): a right to liberty – the right of breaking and reforming political bonds vs. the right to survival/freedom • Contract vs. oath: both declarations contain each form of verbal bond • In both cases, the rhetorical act of declaration was accompanied by, supported by, preceded by violent struggle (the failure of petition as a form of engagement) FOR WEDNESDAY/THURSDAY 19th-century social movement rhetoric: 1848, Declaration of Sentiments Seneca Falls Women’s Rights Convention How does the Declaration of Sentiments imitate the Declaration of Independence? How does it differ?