Civil Rights Movement: Liberty and Equality

advertisement

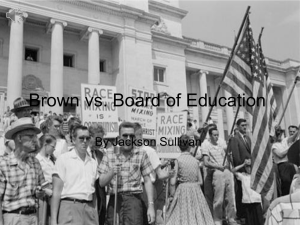

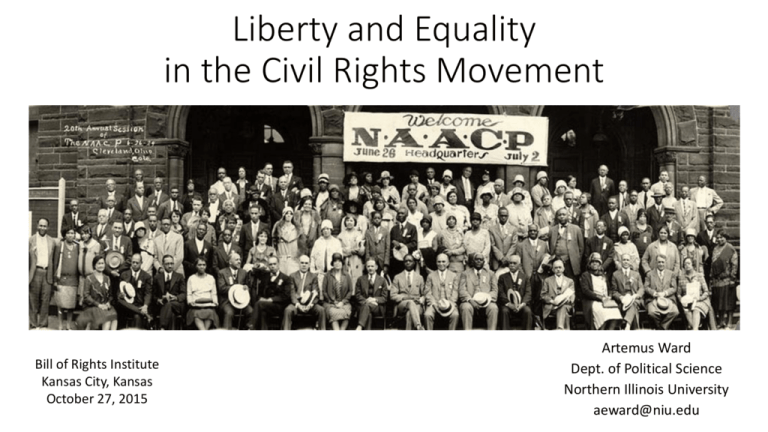

Liberty and Equality in the Civil Rights Movement Bill of Rights Institute Kansas City, Kansas October 27, 2015 Artemus Ward Dept. of Political Science Northern Illinois University aeward@niu.edu Jim Crow Origin • The term Jim Crow is believed to have originated around 1830 when a white, minstrel show performer, Thomas “Daddy” Rice, blackened his face with charcoal paste or burnt cork and danced a ridiculous jig while singing the lyrics to the song, “Jump Jim Crow.” • While traveling in the south, Rice created this character after seeing either a disabled, elderly back man or young black boy dancing and singing a song ending with these chorus words: • “Weel about and turn about and do jis so, Eb’ry time I weel about I jump Jim Crow.” • Some historians believe that a Mr. Crow owned a slave who inspired Rice’s act—thus the reason for the Jim Crow term in the lyrics. • In any case, Rice incorporated the skit into his minstrel act, and by the 1850s the “Jim Crow” character had become a standard part of the minstrel show scene in America. • Youtube: http://youtu.be/T5FpKAxQNKU • Youtube: http://youtu.be/ALTam2L9NhE Jim Crow Laws • Denying black men the right to vote through intimidation and violence was a first step in taking away their civil rights. • Beginning in the 1890s southern states enacted literacy tests, poll taxes, elaborate registration systems, and eventually white only democratic party primaries to exclude black voters. • In Mississippi, fewer than 9,000 of 147,000 voting age African-Americans were registered after 1890. In Louisiana, where more than 130,000 black voters had been registered in 1896, the number plummeted to 1,342 by 1904. • On the local level, most southern towns and municipalities passed strict vagrancy laws to control the influx of black migrants and homeless people who poured into these urban communities in the years after the Civil War. In Mississippi, for example, whites passed the notorious “Pig Law” of 1876, designed to control vagrant blacks at loose in the community. This law made stealing a pig an act of grand larceny subject to punishment of up to five years in prison. Within two years, the number of convicts in the state penitentiary increased from under three hundred people to over one thousand. It was this law in Mississippi that turned the convict lease system into a profitable business, whereby convicts were leased to contractors who sub-leased them to planters, railroads, levee contractors, and timber jobbers. • Jim Crow laws only spread… Consider some examples: • “Any white woman who shall suffer or permit herself to be got with child by a negro or mulatto…shall be sentenced to the penitentiary for not less than eighteen months.” Maryland 1924 • “No colored barber shall serve as a barber to white women or girls.” Atlanta, Georgia, 1926 The Fuller Court 1899. (L-R) Top: Rufus Peckham, George Shiras, Edward White, Joseph McKenna; Bottom: David Brewer, John Marshall Harlan, Chief Justice Melville Fuller, Horace Gray, Henry Brown. Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) • Louisiana passed an 1890 law segregating the races on all railroads. • A group of New Orleans residents of black and mixed-race heritage challenged the law. Their suit was supported by the railroads who found the law too costly to administer. • The group’s lawyer Albion Tourgee selected Homer Plessy to test the law. Plessy was 7/8 white and 1/8 black. • Plessy bought a first class ticket and was arrested. The Fuller Court hears oral argument in the Income Tax Cases, 1895. Old Senate Chamber, U.S. Capitol. Justice Henry Billings Brown for the Court • Writing for the 7-1 majority, Justice Henry Brown (a Lincoln Republican and New Englander who supported the abolitionist movement) said: • “The object of the [14th] amendment was undoubtedly to enforce the absolute equality of the two races before the law, but in the nature of things it could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color, or to enforce social, as distinguished from political equality, or a commingling of the two races upon terms unsatisfactory to either.” • “We consider the underlying fallacy of the plaintiff’s argument to consist in the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it.” Justice John Marshall Harlan Dissenting • In dissent was Justice John Marshall Harlan (an aristocratic Kentuckian whose family had owned slaves). • “The Thirteenth Amendment….not only struck down the institution of slavery…but it prevents the imposition of any burdens or disabilities that constitute badges of slavery or servitude….It was followed by the Fourteenth Amendment, which added greatly to the dignity and glory of American citizenship, and to the security of personal liberty.” • “If a State can prescribe…that whites and blacks shall not travel as passengers in the same railroad coach, why may it not so regulate the use of the streets…to compel white citizens to keep on one side of the street and blacks on the other? Sheriffs to assign whites to one side of a courtroom and blacks to the other? Prohibit the commingling of the two races in the galleries of legislative halls or in public assemblages?” • “The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in the country. And so it is, in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth, and power. So, I doubt not, it will continue to be for all time, if it remains true to its great heritage….But in view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is colorblind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law.” Segregation Bolstered • In response, the legislatures of the South passed segregation laws affecting courtrooms, jails and prisons, restaurants, hotels, bars, trains and train stations, buses, streetcars, elevators, lunch counters, swimming pools, beaches, baseball fields, fishing holes, telephone booths, prizefights, pool halls, factories, public toilets, hospitals, cemeteries, schools, parks, water fountains, libraries, recreational facilities, and almost every other public and commercial facility. • These laws, coupled with segregated private lives, inevitably resulted in two separate societies. Supreme Court After Plessy • In the years after Plessy, the Court applied the precedent to sustain segregation that did not purport to be “separate but equal” as well as a number of other instances of racial discrimination: • Cumming v. Richmond County Board of Education (1899)—the Court refused to interfere with a county school system that provided high school education for whites but not African-Americans. • Berea College v. Kentucky (1908)—the Court sustained a statute requiring private colleges to exclude African-Americans. • Newberry v. United States (1921)—the Court concluded that party primary elections were private affairs, unknown to the framers and therefore beyond the reach of the Constitution. The decision constitutionalized the “white primary” in the one-party Democratic South. • Gong Lum v. Rice (1927)—the Court affirmed the right of Mississippi to segregate Chinese-Americans from public schools set up for whites. Springfield Race Riot (1908) • Throughout American history, white rage has always followed African American activism and progress (e.g. when African Americans fought for their freedom in the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, and the Civil War and after Reconstruction. • On August 14, 1908, white mobs stormed through the African American district in Springfield, Illinois burning homes and destroying business establishments. • It took more than 4,000 militiamen 2 days to restore order. By this time, 2 people had already been lynched, and 2,000 African Americans had fled the city. • Shock waves reverberated throughout the nation that such violence could occur in the North. The racist violence that occurred heightened the need for action and mobilized reformers to act. • A biracial coalition of activists, clergy, and scholars was formed in 1909 as a watchdog of liberties for African Americans. The coalition members sought to create a unified front against future racial injustice and committed themselves to improving the fragile citizenship rights of African Americans. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (1909) • Prompted by the violence Springfield, in 1909 the largest civil rights organization in the United States was founded for the purpose of lobbying, political education, and legal action to alter the status of African-Americans in education, voting, and labor. • W.E.B. DuBois was among the founders of the NAACP and from 1910 to 1934 served it as director of publicity and research, a member of the board of directors, and editor of The Crisis, its monthly magazine. • In its early years (1909-1923), the NAACP focused on ending racial violence—specifically, lynching and mob violence. It raised public awareness through media campaigns, won over American Presidents Woodrow Wilson and Warren Harding who issued public statements against lynching, and secured the support of Congress. • The backlash of white rage against the efforts of the NAACP was palpable and lynchings actually increased. Early Battles for Equality: NAACP • As the scourge of lynchings and the inequality of segregated public facilities grew worse, the disadvantages of the black population increased. The NAACP and its affiliate, the Legal Defense Fund (LDF) fought back through a litigation strategy. • At first, the NAACP relied on volunteer attorneys to bring legal challenges to racial injustice. In its first two decades it participated in a number of Supreme Court cases that expanded the rights of African-Americans: • Guinn v. United States (1915)—submitted a legal brief which helped persuade the Court to overturn the use of the “grandfather clause” to disenfranchise black voters. Though originating in Connecticut in 1818, the grandfather clause was used during the Jim Crow era by 6 southern states as a transparently racist attempt toth circumvent the 15th Amendment. Grandfather clauses released men who were eligible to vote in 1867 (when the 15 was passed), and their legal progeny, from literacy or property requirements for voting. This would ensure that older white illiterates would remain enfranchised. • Buchanan v. Warley (1917)—successfully challenged residential neighborhood segregation ordinances. • Moore v. Dempsey (1923)—successfully argued that federal courts can intervene to protect the procedural rights of defendants who are tried in mob-dominated state proceedings. • John J. Parker Nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court (1930)—played a pivotal role in defeating the nomination after it discovered that Parker had criticized political participation of African-Americans during the 1920 North Carolina gubernatorial campaign. Criminal Justice • In the Scottsboro Cases—Powell v. Alabama (1932) and Norris v. Alabama (1935)—the Supreme Court made clear that it was no longer willing to ignore the blatant racism rampant in southern courtrooms, overturning convictions of black teenagers accused of raping white girls. • Hollins v. Oklahoma (1935) – the first of many decisions declaring exclusion of African American jurors unconstitutional. • Brown v. Mississippi (1936) – ruling that confessions exacted through torture violated the Due Process Clause. • Chambers v. Florida (1940) – establishing that confessions obtained under duress were illegal. • These decisions sent a message to state governments that a criminal trial had to have more than simply the appearance of being conducted in a lawful manner—it had to have substance as well. The Supreme Court had positioned itself as a major institutional player in the politics of race in Jim Crow America. Charles Hamilton Houston • The issue of racial discrimination often coalesced around education. After a debate within the African-American community of whether separate school or integrated schools were desirable, in the 1930s the NAACP began litigation to overturn the separate but equal doctrine. • Charles Hamilton Houston was a key figure in this early movement. He attended Harvard Law School and became the first African-American member of the Harvard Law Review in 1921. In 1924 he began teaching at Howard University and was Dean of the Law School from 1929 to 1935. As Dean, Houston transformed the law school from a traditional part-time operation into a full-time school with a focus on civil rights law. • Houston inspired many of his students, including Thurgood Marshall, who graduated from Howard Law School in 1933, to devote substantial parts of their careers to civil rights law. • In 1935 Houston joined the staff of the NAACP in New York as its first fulltime counsel. He advocated a unified approach to resolving the disparate problems associated with discrimination, segregation, and racial violence. Charles Hamilton Houston Thurgood Marshall (L-R): Thurgood Marshall, Donald Murray, and Charles Hamilton Houston. Murray was the first African-American to enter the University of Maryland School of Law since 1890 as a result of winning the landmark civil rights case Murray v. Pearson (1935), decided in Maryland courts. The Road to Brown Lloyd Gaines Heman Marion Sweatt G.W. McLaurin • In Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada (1938), the NAACP successfully argued that Missouri could not exclude African Americans from its whiteonly law school if the alternative (an out-of-state legal education) was inferior. • In Shelley v. Kraemer (1948), the NAACP persuaded the Court to strike down restrictive racial covenants—private agreements that prohibited local property owners from selling or renting their properties to nonwhites. • Military Desegregation (1948)—Executive Order 9981, issued by President Harry Truman desegregated all branches of the United States military. • In Sweatt v. Painter (1950), the NAACP successfully argued that Texas could not exclude African Americans from its white-only law school if the alternative (a hastily constructed black-only law school) was inferior. • In McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents (1950), the NAACP won again— this time convincing the Court to strike down the University of Oklahoma’s decision to segregate an African-American doctoral student in the classroom, library, and lunchroom. • In Henderson v. United States (1950), the U.S. government joined AfricanAmerican plaintiffs in convincing the U.S. Supreme Court that segregation on interstate railroad dining cars was unconstitutional. Brown v. Board of Education I (1954) • The Browns wanted their daughter to attend the local white-only school in Topeka, KS. The black school was far from the Brown’s home, it was what they considered a dangerous journey, and was in their view inferior. • They lost in the lower courts under the Plessy doctrine. Third-grader Linda Brown (L) and her sister Terri walk through the railroad switchyard on their one-mile journey to the black elementary school. From Vinson to Warren • In 1952, Brown was first heard by the Supreme Court and the justices were split 5-4 with Vinson, Clark, Reed, and Jackson probable dissenters if the Court were to overturn Plessy. • Justice Felix Frankfurter, a former Harvard Law Professor, was so intellectually condescending to Vinson that during one of the Justices' private conferences, Vinson rose from his seat and nearly punched Frankfurter in the nose. Frankfurter later said that Vinson “found it ‘Hard to get away’ from the contemporary view by the framers that the 14th amend did not prohibit segregation—for 90 years segregated schools in the city of Washington.” • The justices knew a divisive decision in the case would be political anathema to the election campaign of 1952, so they decided to schedule the case for re-argument in 1953. But shortly before the Term began, Chief Justice Vinson unexpectedly died of a heart attack. Frankfurter declared on the train back from the funeral, "This is the first indication I have ever had that there is a God.“ • Who would be the new Chief? During the 1952 GOP presidential-nomination campaign, Gen. Dwight Eisenhower made a deal with California Governor Earl Warren (who had run as Thomas Dewey’s VP candidate and narrowly lost to Harry Truman in 1948). Warren would support Ike for President if Ike selected him for the first available seat on the Supreme Court. Ike agreed. Following Vinson’s death, Warren got the appointment. Felix Frankfurter Fred Vinson Waiting for courtroom seats, the Great Hall, U.S. Supreme Court, 1953. The New Chief Justice: From Division to Unanimity • In his memoirs, Justice William O. Douglas (1980, 114-115) recounted the internal politics: • “On December 12, 1953, at the first Conference after the second argument, Warren suggested that the cases be discussed informally and no vote be taken. He didn’t want the Conference to split up into two opposed groups. Warren’s approach to the problem and his discussions in Conference were conciliatory; not those of an advocate trying to convince recalcitrant judges. Frankfurter maintained the position that history supported the conclusions in Plessy that segregation was constitutional. [Justice Stanley] Reed thought segregation was constitutional, and Jackson thought the issue was ‘political’ and beyond judicial competence. [Justice] Tom Clark was of the opinion that violence would follow if the Court ordered desegregation of the schools, but that while history sanctioned segregation, he would vote to abolish it if the matter was handled delicately.” • “It was suggested and decided that the new Chief Justice try his hand at the opinion. Opinions are usually typed the Justice’s office and sent to the printer in the basement, and then two or more printed copies are circulated to each of the other Justices’ offices. This time we suggested that the Chief Justice’s opinion not be circulated but that it be given to each individual Justice privately so that each could express his doubts and uncertainties before a formal opinion was circulated. When circulations are made formally there is always the possibility of a leak, and it was felt we should take the time needed to come up with an opinion that reflected the true opinion of the Court. With these thoughts in mind Chief Justice Warren personally handed to each of us one copy of his draft of his opinion.” The New Chief Justice: From Division to Unanimity • “The four of us who had stood against Plessy the first time these landmark cases were argued transmitted our approval of his opinion to him either orally or by a written note. With Warren we were in the majority, but a five-to-four decision was the last thing any of us wanted. It would not be a decisive decision historically. It would make the issue a political football and would make the filling of the next vacancy on the Court a roman holiday.” • “As the days passed, Warren’s position immensely impressed Frankfurter. The essence of Frankfurter’s position seemed to be that if a practical politician like Warren, who had been governor of California for eleven years, thought we should overrule the 1896 opinion, why should a professor object? The fact that a worldly and wise man like Warren would stake his reputation on this issue not only impressed Frankfurter but seemed to have a like influence on Reed and Clark. Clark followed shortly, Reed finally am around somewhat doubtfully, and only Jackson was left. Jackson had had a heart attack and was convalescing in the hospital, where Warren went to see him. I don’t know what happened in the hospital room, but Warren returned to the Court triumphant. Jackson had said to count him in, which made the opinion unanimous. We could present a solid front to the country, and it was a brilliant diplomatic process which Warren had engineered.” Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the opinion of the Court • What does Warren say about the history and the original intent of those who drafted the 14th Amendment? He said that while historical sources “cast some light” on the question of racial segregation in public schools, they were ultimately “inconclusive.” He explained that there were varying views of what the Amendment meant at the time and furthermore public education for former slaves in the South was disorganized if not non-existent. • Frankfurter’s clerk Alexander Bickel had drafted a memo directing the justices away from historical arguments, which was later revised and published in 1955 in the Harvard Law Review. • “We cannot turn back the clock to 1896 when Plessy v. Ferguson was written. We must consider public education in the light of its full development and its present place in American life throughout the Nation. Only in this way can it be determined if segregation in public schools deprives these plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws.” • What does Warren say about science? • Warren cited a number of social science/psychology studies for the following point: “To separate [black children] from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely to be undone.” • “In the field of public education, separate but equal has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” • The final paragraph of Warren’s unanimous decision asked the attorneys to brief issues regarding implementation and return for oral argument the following year. Thurgood Marshall explains the decision to the press. Brown v. Board of Education II (1955) • The NAACP argued that the Court put an immediate end to racial segregation while attorneys for the southern states argued for gradual implementation. The Court also needed to determine who would be responsible for overseeing implementation. • Warren explained that local school authorities will face various problems with implementation. The federal district courts that first heard these cases will be the best place, based on their proximity, for appraising the local school board’s good faith at implementation. • These courts should exercise traditional “equity power”— balancing both public and private needs. Mere disagreement with integration in not valid. • “To that end the courts may consider problems related to administration, arising from physical conditions of the school plant, the school transportation system, personnel, revision of school districts and attendance areas…on a nonracial basis” and revision of local laws necessary toward these ends. • This is a “transition period.” Public schools should admit children on a racially nondiscriminatory basis “with all deliberate speed.” • When Warren announced the remedy in Brown II in 1955, he utilized an equitable conception that originated years earlier with Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.: "with all deliberate speed.“ Where did this controversial phrase come from? • In a draft of the decree prepared by Justice Frankfurter on 8 April 1955, which Warren subsequently adopted, Frankfurter used the phrase "with all deliberate speed" to replace "forthwith," the word proposed by National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) lawyers to achieve an accelerated desegregation timetable. Frankfurter wanted to anchor the decree in an established doctrine associated with the revered Holmes, but his endorsement of "all deliberate speed" sought to advance a consensus held by the entire Court. Each justice thought that the decree should provide for flexible enforcement, should appeal to established principles, and should suggest some basic ground rules for judges of the lower courts, who would implement the Brown decision. • Shortly after he retired from the Court, Warren acknowledged that "all deliberate speed" was chosen as a benchmark because "there were so many blocks preventing an immediate solution of the thing in reality that the best we could look for would be a progression of action." • When it became clear, however, that critics of desegregation were using the doctrine to delay and avoid compliance with Brown, the Court began to express reservations about the phrase. In 1964, less than a decade after "all deliberate speed" was prescribed, Justice Hugo Black declared in a desegregation opinion that "[t]he time for mere 'deliberate speed' has run out." “All Deliberate Speed” Black Monday (1954) • Arkansas and Virginia closed down their entire public school systems rather than implement Brown. • African-American student Emmit Till was murdered in Mississippi in August 1955, just after Brown II was decided. • U.S. Representative John Bell Williams (D-Mississippi) coined the term "Black Monday" on the floor of Congress to denote Monday, May 17, 1954, the date of the Supreme Court's decision. • In opposition to the decision, white citizens' councils formally organized throughout the south to preserve segregation and defend segregated schools. • The White Citizens' Council movement in Mississippi, led by Thomas Pickens Brady, a circuit court judge, published a handbook, Black Monday, in which the philosophy of the movement is stated, including its call for the nullification of the NAACP, the creation of a forty-ninth state for Negroes, and the abolition of public schools. The Murder of Emmett Till (1955) • Till was a 14-year-old boy from Chicago who was visiting relatives in the town of Money located in the Delta region of Mississippi. • He spoke to 21-year-old Carolyn Bryant, the married proprietor of a small grocery store there. Several nights later, Bryant's husband and his half-brother went to Till's great-uncle's house. They took Till away to a barn, where they beat him and gouged out one of his eyes, before shooting him through the head and disposing of his body in the Tallahatchie River, weighting it with a 70-pound cotton gin fan tied around his neck with barbed wire. Three days later, Till's body was discovered. retrieved from the river, and returned to Chicago. • Till’s mother had a funeral with an open casket to highlight the brutality of white southern rage. Tens of thousands attended the funeral or viewed the casket and helped galvanize the civil rights movement. • The white men who murdered him were acquitted at trial. One of his killers said Till “looked like a man.” This is a common justification for white rage and recurs in news accounts of lynchings of black boys and girls from 1880 to the early 1950s, in which witnesses and journalists fixated on the size of victims who ranged from 8 to 19 years old. These victims were accused of sexually assaulting white girls and women, stealing, slapping white babies, poisoning their employers, fighting with their white playmates, or protecting black girls from sexual assault at the hands of white men. Or they were lynched for no reason at all. The Southern Manifesto (1956) • In 1956, 19 U.S. Senators and 77 Congressman signed “The Southern Manifesto: A Declaration of Constitutional Principles,” in which they pledged “to use all lawful means to bring about a reversal of this decision which is contrary to the Constitution and to prevent the use of force in its implementation.” • The manifesto further said that the Brown decision was “destroying the amicable relations between the white and Negro races that have been created through 90 years of patient effort by the good people of both races.” Sen. Strom Thurmond prepared first draft of Southern Manifesto repudiating the Supreme Court's 1954 school desegregation decision. February 1956. The Hollow Hope? This photograph shows the results of the Brown decision with both black and white students in the same classroom at Anacostia High School in 1957. Today Anacostia, like many of the public high schools in D.C. is attended by predominantly African American students. • Did Brown integrate the schools? • In 1954, .001% of black students attended schools with whites in southern and border states. In 1955 there was a slight upward trend to .12%. • Yet there were no significant changes until the 1970s: 1965 (6%); 1966 (17%); 1968 (32%); 1970 (86%); 1972 (91%). • These changes were largely due to forced busing programs. Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955) • On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks, forty-three, was arrested for disorderly conducted for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white passenger. Her arrest and fourteen dollar fine for violating city ordinance, led African American bus riders and others to boycott the Montgomery city buses. • It also helped to establish the Montgomery Improvement Association led by a then unknown young minister from the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Martin Luther King, Jr. The boycott lasted for one year and brought the Civil Rights Movement and Dr. Martin King to the attention of the world • In Gayle v. Browder (1956) the Court silently overturned Plessy by upholding a declaratory judgment invalidating statues requiring segregation on public transportation in Montgomery, Alabama. The Civil Rights Act of 1957 • It is important to understand that Brown is an example of how the Supreme Court cannot affect social change on its own. Instead, Brown should be understood as merely one step in the larger civil rights movement that involved protests, marches, legislation, and litigation. • The Civil Rights Act of 1957 was the first civil rights law passed by Congress since Reconstruction. It was designed to secure the right to vote for blacks. Little Rock Nine (1957) • The NAACP worked with southern school districts to implement Brown. In Little Rock, Arkansas, the school board agreed to gradual integration of the school beginning in fall 1957. • The NAACP chose nine exemplary African American students (based on grades and attendance) to attend the previously all-white Little Rock Central High School. • Segregationists threatened to physically block the students from entering the school and Governor Orval Faubus deployed the Arkansas National Guard to support the segregationists. The sight of soldiers blocking the schoolhouse door made national headlines. • President Dwight Eisenhower ultimately federalized the Arkansas National Guard and sent U.S. Army troops to protect the nine students who enrolled and attended classes that year—though they were continually harassed by white students and others. • The next year, Faubus—with the support of the school board—closed the public schools and sought to establish private-school-only education. He failed, membership on the school board changed, and after the “lost year” of 1958, the integrated public schools reopened in 1959—though African American students continued to face harassment. The "Little Rock Nine" are escorted inside Little Rock Central High School by troops of the 101st Airborne Division of the United States Army. The Civil Rights Movement • Black and white Freedom Riders were attacked and brutally beaten, their buses sometimes burned, by angry white mobs wielding ax handles, bicycle chains, and baseball bats, often times while local law enforcement stood by and watched. • Throughout the 1960 presidential campaign, Jack Kennedy had dramatized the plight of African-Americans and they supported his nomination and election. • On the eve of the 1960 presidential election the Kennedy brothers engineered the release of Martin Luther King, Jr. and others who were arrested in Georgia for sitting at a white-only lunch counter. King had been sentenced to prison and many felt King would be killed while being transported from jail to his prison cell. Some say the Kennedys saved King’s life. • After they took office, the Kennedys proposed a sweeping Civil Rights bill which was ultimately passed in 1964. • The civil rights education of the Kennedys by the movement was exemplary of how bottom-up activism can influence insulated elites and lead to political and legal change. March on Washington (1963) •The assembly of an estimated quarter of a million people on the Mall between the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument on August 28th, 1963, was the March on Washington. “It was the biggest, and surely the most diverse, demonstration in history for human rights,” wrote Milton Viorst in Fire in the Streets: America In The 1960's. It was also a march that was 22 years in the making, a march that began as a threat and ended as a triumphant restatement of the goal of human freedom embodied in the Constitution. •Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech at this event. •What many people do not know is that opening for King and other speakers were: Gospel legend Mahalia Jackson who sang “How I Got Over,” Bob Dylan who performed several songs, including “Only a Pawn in Their Game” about the culturally fed racial hatred amongst Southern whites that led to the assassination of Medgar Evers and “When the Ship Comes In” during which he was joined by fellow folk singer Joan Baez, who earlier had led the crowds in several verses of “We Shall Overcome” and “All My Trials.” Peter, Paul and Mary sang “If I Had a Hammer” and Dylan’s “Blowin' In The Wind.” They were all in their early-to-mid 20s. •Youtube: Jackson’s March on Washington performance: http://youtu.be/TALcOreZi0A •Youtube: Dylan’s March on Washington performance: http://youtu.be/WLwHnNybADo •Youtube: King’s speech: http://youtu.be/smEqnnklfYs Civil Rights Act of 1964 Voting Rights Act of 1965 • The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a major enactment designed to erase racial discrimination throughout American life. The act forbids discrimination based on race, color, religion, national origin, and, in the case of employment, sex. (Discrimination in housing is covered under the Civil Rights Act of 1968). • Major provisions of the Act: 1. Outlawed arbitrary discrimination in voter registration and expedited voting rights suits; 2. Bared discrimination in public accommodations, such as hotels and restaurants, that have a substantial relation to interstate commerce [Title II]; 3. Authorizes the national government to bring suits to desegregate public facilities and schools; 4. Extended the life of and expanded the power of the Civil Rights Commission; 5. Provided for the withholding of federal funds from programs administered in a discriminatory manner. 6. Established the right to equality in employment opportunities. 7. Established a Community Relations Service to help resolve civil rights problems. • The Voting Rights Act of 1965 followed and helped increase voting among African Americans in the South. Conclusion: The Unfinished March • The civil rights movement of the 20th Century was only partially successful at ending racial discrimination. • The NAACP’s litigation strategy, which included the landmark victory in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) was only as successful as the larger civil rights movement was more generally. • While legal victories in courts and legislatures provided positive gains for racial minorities, the momentum would ultimately dissipate and begin to reverse as America became more conservative at the close of the century. • Supreme Court decisions reflected the turn to the right by striking down racial quotas, sustaining some forms of de facto discrimination in education, and gutting the voting rights act. Conclusion: The Unfinished March • In a report titled “The Unfinished March,” the Economic Policy Institute found that school segregation, black unemployment, lack of access to fair housing and living wages, and abysmal African American household wealth remain at essentially the same levels of disparity today as they did in 1963, when the March on Washington occurred. • Median household wealth today is $141,900 for whites and only $11,000 for blacks. • Despite making up only 13% of the population, black Americans are 27% of those living at or below the poverty line. • The white unemployment rate is 4.6%, while it’s 9.6% for blacks During the housing bubble of the mid-2000s, 53% of blacks received high-cost mortgages, while only 18% of whites did. • The black incarceration rate is 2,207 per 100,000, compared with the national rate of 707 per 100,000. • Nearly 3 in 4 black children today attend segregated schools. • In many communities, blacks have poorer health outcomes and access to just half the social services of whites. The list goes on ad nauseam. • These statistics make plain that the African American struggle for liberty and equality is not complete.