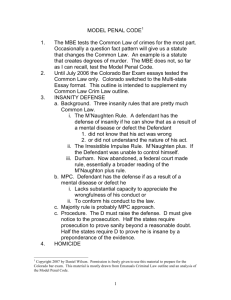

Crim Bullet Outline

advertisement

CRIM OUTLINE SUBSTANTIVE LAW Homicide Murder o Elements Conduct on the part of the defendant (actus reus) Malicious state of mind (mens rea) Intent to kill o Use of deadly weapon as rebuttable presumption o Does not require hatred or ill will, merely the intent to kill Intent seriously to injure o Must be more than plain bodily injury o Generally requires subjective understanding of the extend of the danger o The MPC does not recognize this, but does recognize extreme recklessness (which may capture most cases) Extreme recklessness o More than negligent or unjustifiable o Should reasonably be expected to create a very high degree of risk of death or serious bodily injury o Some courts and the MPC create a subjective standard, other courts create an objective standard o Intoxication Not generally a defense But, drunk driving is usually not extreme recklessness murder unless it’s pretty extreme—100 mph, a bunch of near-misses, etc. Intent to commit a felony (Felony Murder) o Law implies the mens rea from the felony o Law generally requires dangerous felonies Example: Enron executive, during flourish while signing a document committing a financial felony, stabs secretary to death with pen by accident: no murder This may be judged Abstractly (narrower): is this type of crime dangerous when described abstractly Particular facts (broader): is this particular crime dangerous from its own facts o There must be a causal relationship Example: While a bank robbery is occurring, a teller dies of old age: no murder Must generally be a “natural and probable consequence” o Gunfights Robber shoots victim or bystander: slam dunk murder Victim or cop shoots bystander Some states, no liability Other states, who shot first Robber shoots robber: courts split Victim or cop shoots robber: most courts say no liability for other robber o “In the commission of” a felony Generally, the time during which felony murder is chargeable is until the felon(s) are at rest o Independence requirement Where the felony is an included offense in the killing, there is no felony murder Example: A person commits voluntary manslaughter. The prosecutor argues that the murder occurred in the commission of the felony of voluntary manslaughter, and thus the defendant is chargeable with felony murder. This argument will fail. o MPC rejects the rule as illogical—it is a mere fortuity that someone does or does not die during a felony; the penalty for the felony itself should incorporate the likelihood of death (Resisting lawful arrest) The conduct must legally cause the death of a living human-being victim Causation (proximate cause) o Substantial factor in causing the death o Cannot be brought about in a manner to greatly different from the intended manner o (The death must occur within a year and a day) Living human-being o The person must be fully born Unless the fetus would survive in the natural course of events (Chavez) Unless in a state with a statutory provision for fetuses Example: Keeler v. Superior Ct, ex-husband kicked wife in stomach, killing fetus; no crime against baby Subequently, Cal. enacted a law o The person cannot be dead already Proof of death (corpus delicti) o Degrees MPC does not use degrees; instead, it instead gives mitigating and aggravating factors that can be used in determining whether the death penalty should be imposed First Premeditated and deliberate o Traditional view: no set amount of time for premeditation o Modern view: this arrogates nearly all murders to first degree; the proper test is a “reasonable period of time” o It’s not automatic that a murder that takes a long time (e.g. strangulation) allows premeditated (even though you might deliberate while you are doing it) Intoxication may negative premeditation Elements that help prove premeditation o Planning o Motive o Manner tending to show a preconceived design Old cases talk about lying in wait, torture, and poison Second The default degree of murder Include o No premeditation o Intent seriously to injure o Extreme recklessness / depraved heart o Felony murder (usually; some jurisdictions consider felony murders related to rape, robbery, arson, or burglary to be first degree murder) Manslaughter o Voluntary Provocation Conduct otherwise constituting murder may be mitigated to voluntary manslaughter provided there is adequate provocation, causing a killing in the heat of passion Elements o Action in response to a provocation that would cause a reasonable person to lose self control o Defendant was actually in the heat of passion o Lapse of time is not enough for a reasonable person to cool off o Defendant had actually not cooled off Reasonable person standard o Courts sometimes allow the reasonable person to be endowed with physical or categorical characteristics, but many are not Example: The reasonable impotent teenager standard; the reasonable battered woman standard o Courts almost never allow emotional characteristics, such as quickness to anger or the like, to set the standards of a reasonable person Categories o Battery / assault This not a self-defense theory, so the question is of provocation (i.e. anger), not of fear o Mutual combat—neither party clearly the aggressor o Adultery Usually must be spouses, not fiancé / fiancée o Words Generally not adequate Performative and informative words might Example: A spouse informs the other spouse of infidelity: this may be adequate provocation Most jurisdiction allow reasonable mistakes o A reasonable but mistaken belief in adultery, e.g. o Killing by bad aim is allowed o But anger that leads to lashing out and killing a known innocent party is not usually manslaughter (MPC might allow this) Imperfect self defense o Involuntary Criminal / gross and culpable negligence Standard of reasonable care o Generally exceeds the standard required for tort negligence o Criminal negligence is more likely to lie where a person uses an inherently dangerous object like a gun Awareness of danger o Jurisdictions are split as to whether the defendant must know about the danger of his conduct; the MPC and many states require that the defendant be aware of the danger Proximate cause o As with tort negligence, the death must be the proximate cause of the conduct o Contributory negligence is not necessarily a bar Misdemeanor manslaughter Involuntary manslaughter may lie if the conduct leading to the death was a misdemeanor Generally the conduct must be malum in se or at least bear a close causal link The MPC has abolished this Legal duty Statutory duty, status, contractual duty, voluntary assumption of care to prevent others from rendering aid In these circumstances, acts of omission leading to death may be chargeable as involuntary manslaughter, or if done in the hopes of causing death, as murder Defenses o Self-defense Elements Resist unlawful force o Self-defense will fail as against lawful force o Example: A person is caught attempting to steal a bicycle; the owner shoves him away from the bicycle. The would-be thief cannot attack the owner because the force the owner used was lawful. The harm must be imminent o Example: A threatens to kill B tomorrow. A goes to B’s house and kills him. This is not self-defense. o If a person begins but then clearly renounces an attack, the other person can no longer claim self-defense. Force must not be excessive Defendant cannot have been the aggressor unless o He was the aggressor with non-deadly force met unexpectedly by deadly force, or o He withdrew from his aggression and the other party pressed the attack Defendant must retreat if he can do so in complete safety unless o The attack took place in defendant’s house (if the state recognizes a castle doctrine) or o He uses non-deadly force Mistake Reasonable mistakes are permitted Unreasonable mistakes and excessive force resulting in death will be “imperfect self defense” chargeable as voluntary manslaughter Battered Woman’s Syndrome Generally considered as part of the reasonableness prong of the selfdefense inquiry Where a woman through years of abuse has a special awareness of her husband’s behavior (e.g. red baseball cap = beating), the court can take notice of this o Defense of Another Same rules as self-defense—you stand in the shoes of the person you’re defending Exception: the modern rule is that if you make a reasonable mistake that the person your defending wouldn’t have had occasion to make, you can still raise this defense o Duress and Necessity Duress A threat that overbears the will of the defendant Elements o Threat by a third-person o Producing reasonable fear in the defendant o That he will suffer immediate or imminent o Death or serious bodily harm Generally speaking, the harm to which the defendant consents must be less than the harm he causes; this is why it’s usually not available as a defense to intentional homicide (the MPC would allow this) Necessity Generally is the choice of a lesser of evils o Typically, therefore, necessity cannot justify killing o Example: Hunter appears ready to shoot you, having mistaken you for a deer. Necessity will not justify killing the hunter (although self-defense probably will). o Example: The switch in the railyard that will direct the train to run over one rather than two workers would be justified by necessity. Elements o Greater harm o No alternative o Imminence o Situation not caused by defendant o Nature of harm MPC does not rule out homicide as a necessity Theft Larceny o Distinguished Versus embezzlement: “Was the possession originally obtained lawfully?”— If yes, the crime is embezzlement; if no, it’s larceny Versus false pretenses: “What was obtained unlawfully—mere possession or title?”—If possession was obtained unlawfully, the crime is larceny; if it’s the title, it’s false pretenses o Elements Trespassory taking The animus ferandi must exist at the time of the trespassory taking; thus, a decision to keep another’s property is not a trespassory taking Where a transaction is to take place in the owner’s presence, the owner retains constructive possession, as, for example, in a drive off without payment at a gas station Mislaid / misdelivered property o If you intend to keep it when you find / receive it, that is a trespassory taking o If you look for the owner but then decide to keep it, this is not larceny, except that under the MPC, which requires a reasonable effort to find the owner Larceny by trick distinguished from false pretences o Larceny by trick involves taking possession by lying Example: A rents a car, and has no intent of paying or returning it (the person at the rental counter doesn’t think A is getting title). o False pretences involves taking title by lying Example: A passes a forged check to pay for a book (the person at the counter does think A is getting title). Carrying away (asportation) Even a short distance is sufficient Personal property of another Common law required the good be tangible, but now it can include stocks and bonds, etc Common law did not consider it theft to take what you “stole” something in which you were a co-owner With intent permanently to deprive (animus ferandi) Must intend to deprive permanently or to cause owner a substantial deprivation The only issue is what the person’s intent is at the time of the trespassory taking, not the outcome Statutory schemes have altered this somewhat o Joyriding statutes o Prohibitions on ransoming chattels, claiming an item was previously purchased to receive a refund, etc Is not met where a person takes something under a claim of right (e.g., repossession), even if the claim of right is unreasonably mistaken (because it negatives the intent) Embezzlement o Elements Fraudulent As with larceny, probably even an unreasonable mistaken claim of right negatives this element o Debt collection is therefore not embezzlement The intent to repay is not a defense against embezzlement Conversion of This is distinct from asportation It requires depriving the owner of a significant part of the property’s usefulness o Example: A person caught trying to steal the company car one mile from the office is probably not guilty of embezzlement (yet, although probably of attempted embezzlement) The property of another One cannot embezzle where one is a co-owner at common law Fraudulent failure to make payment of a debt is not embezzlement because the money is not yet the property of another By one who is already in lawful possession of it This is the primary distinction from larceny—this is often carried out by employees o Does not overlap with larceny False Pretenses o Elements False representation of a material present or past fact False statement Affirmative nondisclosure or concealment Usually not silence False promises are not usually enough, but a minority of courts say yes Which causes the person to whom it’s made The reliance must arise from a material and true belief To pass title to his property to the misrepresentor, who This requires a sale, not a loan or lease The changing hands of money usually signifies the passing of title (unless the money is to be put to a particular person, e.g. for deposit in a bank account, in which case the crime is larceny by trick) Knows that his representation is false and intends to defraud It is sufficient to show that the defendant o Knows he’s lying o Believes but isn’t sure he’s lying o Knows he doesn’t know if he’s telling the truth Burglary o Elements Breaking and entering With the intent to commit a felony (or misdemeanor) therein o Modified from common law (required dwelling and at night) Robbery o Elements Larceny With property taken from the person or in his presence By using force or fear Rape Elements: o Unlawful sexual intercourse Does not require emission May be vaginal only, may be anal or oral (or these might fall into a “deviate sexual intercourse” statute Spousal exemption States are abandoning this, but at common law a husband could not rape his wife Many states consider this a lesser crime than the rape of a stranger o (With a female) now mostly abrogated o Without her consent Some states require consent to be clearly withheld, others that it be clearly communicated Some states automatically assume lack of consent where the victim is drugged or intoxicated, others only when the perpetrator is responsible for the victim’s condition Fraud Consent is effective where fraud did not concern the essence of the act but ineffective where it does concern the essence of the act o Example: A doctor tells a patient that sex is necessary for treatment; the consent thereby obtained will be effective o Example: A doctor obtains the patient’s permission to perform a medical procedure and while the patient is under general anesthetic, the doctor has sex with her Mistake of consent The majority of states consider rape a crime of general intent, so the intent to have sex is sufficient to establish rape even if the mistake was reasonable Some states have a negligence standard for mistaken consent Force Most states apply only with force o Some states have held that penetration itself is force o Threat of force is a sufficient substitute in almost all states Resistance o A majority of states don’t require resistance o Some states require reasonable resistance (but no longer “to the utmost”) o Statutory Reasonable mistake usually not a defense MPC allows reasonable mistake Insanity As a defense o M’Naghten Rule Insanity requires proof that the criminal was “labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or, if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong.” Elements Mental defect or disease Result o Did not understand “nature” or “quality” of act; or o Did not know act was wrong It’s unresolved whether this means wrong with respect to society’s rules, or wrong in an absolute sense It does apply to the act in question, not a person’s overall failure to discern right from wrong Irresistible impulse About half of the M’Naghten states (which is itself the majority rule) allow an “irresistible impulse” defense Irresistible o Doesn’t actually mean irresistible, just a substantial impairment to capability Impulse o Can be premeditated; needn’t be impulsive o Durham Test Encompasses the M’Naghten rule with the irresistible impulse portion Allows insanity acquittal “if his lawful act was the product of mental disease or defect” This rule is not broadly accepted o MPC Test MPC § 4.01(1): “a person is not responsible for criminal conduct if at the time of such conduct as a result of mental disease or defect he lacks substantial capacity either to appreciate the criminality of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the requirements of law” MPC is also a minority rule, although federal courts use it o Burden of proof The defendant generally has the burden of raising the defense There are no constitutional requirements respecting the party with the burden of proof or what the burden is As grounds for commitment o A state can impose a mandatory commitment on an insanity acquitee without any additional proceeding o But, a person cannot be held indefinitely without process, pretrial, pending the determination of his fitness to stand trial; the state must either release him or establish the need for commitment through normal means o The committed person bears the burden of showing either that he is no longer insane, no longer dangerous, or ideally both (probably to a preponderance standard) o Note: people can disappear pretty much forever if they’re committed Other factors Intoxication o Voluntary intoxication is not an excuse o It may defeat intent Mistake o Fact Mistake of fact can be used to defeat elements of a crime, usually intent Mistake of fact cannot generally be used to defeat a crime by itself (it’s still attempt if you try pickpocketing an empty pocket) You might not be in trouble if you try by ridiculous means (voodoo doll) o Law Not a great distinction Generally not a defense unless you do something that you think is illegal but isn’t Strict liability o Is constitutional Attempt Liability has been broadening with respect to mental state, proximity to the act, and the defense of impossibility There is typically an intent requirement o Thus, where a crime requires bringing about a certain result—like involuntary manslaughter—it cannot be attempted o A crime not defined by result, like recklessness, can be attempted—Example: your car with bad brakes won’t start—this might be attempted reckless driving o The law is unclear on attempt to commit a strict liability crime without intent Attempt v. mere preparation o Proximity—how close the person came “Dangerous proximity to success” o Equivocality—how clear it is from your acts that you intended to commit the crime o MPC—combination “an act or omission constituting a substantial step in a course of conduct planned to culminate in . . . [defendant’s] commission of the crime” Must also be “strongly corroborative of the actor’s criminal purpose” MPC would overrule Rizzo Conspiracy Mere knowledge of supplier / service provider is generally insufficient; held sufficient in cases of o Stake in venture o Controlled commodities o Inflated charges o Large proportion of sales o Serious crime Parties to conspiracy o Wheel / hub conspiracy One large conspiracy only if “community of interest” If “spokes” don’t know about each other or aren’t a “community of interest,” there are multiple conspiracies o Chain conspiracies “Community of interest” still important Not necessary for parts to know about one another o Critiques of these labels Pinkerton rule o All participants in the conspiracy are liable as principals for the substantive crimes committed by each in furtherance of the conspiracy o Only applied in some states, rejected in MPC Overt act requirement o At common law, the conspiracy is complete upon agreement by parties o Half of states require an overt act o MPC requires overt act only for non-serious crimes Duration of conspiracy o The conspiracy ends when the agreement ends Abandonment by all Completion of the crime Withdrawal Generally must actually or constructively provide notice to each conspirator Also could tell the police o Continuous cooperation is continuous participation in the conspiracy, even if there are discrete acts comprising the conspiracy o Acts of concealment are not a continuation of the conspiracy o Defense Common law rule – conspiracy is complete when the agreement is reached so no defense to withdraw MPC – if you must voluntarily withdraw and then thwart the conspiracy, typically by telling the police Plurality o A conspiracy must be between two or more human beings o Spouses used not to be punishable, but this is rejected today o Feigned agreement Traditional rule – if one party is a cop and the other is a would-be criminal, there can be no conspiracy because there is no actual agreement Modern / MPC rule – conspiracy is determined by a unilateral approach o Inconsistent disposition Same trial – most (all?) jurisdictions require A and B both to be convicted or not Different trials – inconsistency is fine One conspirator not brought to justice – no problem in convicting other MPC – gets rid of this entirely o The Wharton Rule There can’t be a conspiracy if you can’t commit the substantive offense without the cooperative action of the number of people in the conspiracy Thus, it’s not a conspiracy to commit adultery if two people are involved, but it could be if three people are involved This is now sometimes considered merely a judicial presumption, and the MPC rejects it entirely Non-criminal objectives o An old rule (in some states) punishes conspiracy to commit an “unlawful” but not illegal act (something against morals, triggering tort liability, etc) o Example: woman who got girl to kill herself by taunting her over the internet CRIMINAL PROCESS Overview Arrest Initial Appearance o Gerstein v. Pugh, 420 U.S. 103 (1975) Created requirement for “Gerstein hearing” Requires cursory determination of probable cause o Typically must occur within about 48 hours (Riverside v. McLaughlin) o No right to counsel at this point (because the initial appearance is a Fourth, not Sixth Amendment requirement) o The concern is that you will be put in jail indefinitely while the police investigate; now material gathered after a reasonable time has passed is inadmissible Appointment of Counsel o Based on income o Right to appointed counsel raises question: why do you have to pay for anything if you’re presumed innocent? Why not pay for everything? o United States v. Gipson, 517 F. Supp. 230 (W.D. Mich. 1981) “Financial inability as considered for the purposes of the Act does not mean indigency. The Defendant does not have to be destitute to be eligible for an appointment of counsel. The Court need only be satisfied that the representation essential to an adequate defense is beyond the means of the Defendant.” Id. at 231. Preliminary Examination o Coleman v. Alabama, 399 U.S. 1 (1970) Held that the Sixth Amendment right to counsel attaches at the preliminary examination o This is a hearing before a judge to determine whether there is sufficient probable cause to bind the person over, either to trial or to the grand jury phase o This is often waived Bail o Stack v. Boyle, 342 U.S. 1 (1951) “[T]he modern practice of requiring a bail bond or the deposit of a sum of money subject to forfeiture serves as additional assurance of the presence of an accused. Bail set at a figure higher than an amount reasonably calculated to fulfill this purpose is ‘excessive’ under the Eighth Amendment.” Id. at 5. o United States v. Salerno, 481 U.S. 739 (1987) “[U]pheld the power of a federal court . . . to detain an accused prior to trial on the basis that the accused posed a danger to the community. Traditionally, bail was generally denied to an accused only if a court found that the accused posed a risk of flight.” Lexis Notable Case Analysis. “[The] Court for the first time upheld the constitutionality of adult preventive detention, holding that society’s interest in a safe community could outweigh the rights of an accused, even if the accused was charged with a nonviolent crime.” Id. o “Bail is an absurdity”: it can’t really accomplish its purpose because there may be no overlap between the amount of money you can get and the amount of money necessary to keep you from running Decision to Prosecute Indictment o United States v. Williams, 504 U.S. 36 (1992) Held that it was not a constitutional requirement that prosecutors provide exculpatory evidence to grand juries because procedural protections don’t necessarily attach to grand jury proceedings Discovery o Fed R. Crim. Proc. 16 Right to a Speedy Trial o United States v. Marion, 404 U.S. 307 (1971) Held that Sixth Amendment speedy trial right does not attach until the defendant is formally charged or arrested o Barker v. Wingo, 407 U.S. 514 (1972) Created four-part balancing test for Sixth Amendment delay; upheld a five year delay Length of the delay Reason for the delay Whether the defendant asserted his right Prejudice to the defendant Plea-Bargaining o Fed. R. Crim. Proc. 11 Judge has to make sure the defendant knows what he’s doing by describing what rights he’s waiving, making sure it’s voluntary, and assuring there is a factual basis for the plea o Brady v. United States, 397 U.S. 742 (1970) “[T]he Supreme Court held that a guilty plea is not compelled and invalid under the Fifth Amendment when it is motivated by a defendant’s desire to accept the certainty or probability of a lesser penalty rather than face a wider range of possibilities extending from acquittal to conviction and a higher penalty authorized by law for the crime charged.” Lexis Notable Case Analysis. This is the most important plea bargaining case—the Supreme Court accepted what had previously been a closed-door sort of a thing o North Carolina v. Alford, 400 U.S. 25 (1970) Held that it is not a violation of the Fifth Amendment where a defendant protests his innocence but pleads guilty to reduce his sentence (or avoid the death penalty, as here) This merely holds that it’s constitutional; many state courts require the person to admit guilt Makes an unusual person liberty argument: it respects a person’s liberty to allow them to make the plea they want, even if they’re innocent o Bordenkircher v. Hayes, 434 U.S. 357 (1978) Held that there was no violation of due process for a DA to threaten to bring an additional charge if the person didn’t plead guilty provided that charge was supported by the evidence o An automatic sentence reduction would be unconstitutional because it penalizes the assertion of Fifth Amendment rights—notice how close Bordenkircher gets Trial o Illinois v. Allen, 397 U.S. 337 (1970) Held that where a defendant is disruptive to the trial, it is not a violation of the confrontation clause of the Sixth Amendment to kick him out of the courtroom o Faretta v. California, 422 U.S. 806 (1975) Held that there is a right implied by the Sixth Amendment to self representation Courts needn’t tolerate a defendant who engages in obstructionist conduct, and can require a standby counsel Voir Dire o Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986) Allows a person to raise an inference of purposeful discrimination in the voir dire which shifts the burden to the DA to show there is no discriminatory intent “Batson’s holding has been expanded by later cases to prohibit discrimination on the basis of religion and gender and to allow a Caucasian defendant to allege discrimination by the exclusion of African American jurors from his panel.” Lexis Notable Case Analysis. o If voir dire works (dubious), isn’t this the best reason not to allow it? Prosecution and Defense o United States v. Agurs, 427 U.S. 97 (1976) “When a defendant makes “no request . . ., or when the request was general, there was no requirement that evidence be disclosed merely because it might ‘influence’ the jury. Constitutional error existed only if the omitted evidence created a reasonable doubt that did not exist without the evidence.” Lexis Notable Case Analysis. Weinreb: “Looking at all the evidence of this case, would this have changed it?” Best practice for a defense attorney: (1) look for everything stuff by name; (2) look for stuff by specific description; (3) as for criminal records; (4) throw in boilerplate for some protection from Agurs o The typical discovery for the defense attorney includes the witnesses’ criminal records o Arizona v. Youngblood, 488 U.S. 51 (1988) “The Court held that unless a defendant could show bad faith on the part of the police, the failure to preserve potentially useful evidence did not constitute a denial of due process.” Lexis Notable Case Analysis. o Hitch v. Pima County Superior Court, 708 P.2d 72 (Ariz. 1985) Held that if an attorney received inculpatory evidence, she must turn it over to the state if she believes the person would destroy it; otherwise she may give it back to the person o Nix v. Whiteside, 475 U.S. 157 (1986) Held that an attorney does not violate his client’s Sixth Amendment rights by refusing to suborn perjury Indeed, the attorney may not do so o Johns v. Smyth, 176 F. Supp. 949 (E.D. Va. 1959) An attorney who refuses to present evidence because it runs against his conscience violates a client’s Sixth Amendment rights Sentence o Williams v. New York, 337 U.S. 241 (1949) Sentencing judges may use broad sources of information in sentencing defendants, not limited by the due process requirements of trial o United States v. Grayson, 438 U.S. 41 (1978) A judge may take cognizance of the defendant’s lying at trial in sentencing the defendant o Mandatory sentencing unconstitutional (Booker), but valid as guildines o Three cases Weinreb mentioned Apprendi v. New Jersey, 530 U.S. 466 (2000) “[A]llowed sentencing judges to enhance defendants’ sentences based on factors that were established by a preponderance of the evidence at a sentencing hearing rather than proved to a jury beyond a reasonable doubt.” Lexis Notable Case Analysis. Blakely v. Washington, 542 U.S. 296 (2004) “[W]hen a law required a judge to increase a defendant’s sentence upon finding an increment of culpability, it had to ensure that the judge’s finding was grounded in a jury’s verdict if not the defendant’s Sixth Amendment rights . . . .” Lexis Notable Case Analysis. United States v. Booker, 543 U.S. 220 (2005) “The Supreme Court of the United States decided . . . Booker, applying the ruling in Blakely . . . to the Federal Sentencing Guidelines and determining that the mandatory application of the Guidelines violated the right to trial by jury under the Sixth Amendment.” Lexis Notable Case Analysis. Troubling Elements o Long delays without any purpose o Reliance on guilty pleas o Dominance of lawyers—distorts things without any compensating tendency to find truth, do justice, etc