Clare Painter Plenary ISFC39 2012

advertisement

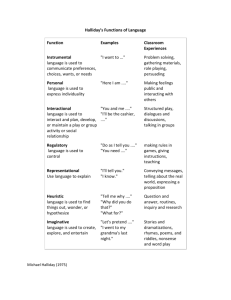

Guidance in the context of shared experience: the role of interaction in language and literacy development Clare Painter University of Sydney ISFC 2012 1 our predisposition to teach • a back-up strategy has survived in the many species that are specifically social: the same lifelong chemistryplus-environment strategy that results in children who are primed to learn also results in adults who are primed to teach. The selective sensitivity of the child gets tuned to a reliable source of information, reliable because that source -- other people in its community -has similarly evolved to provide just that kind of information (e.g. about the local language in use in the community in that generation). The child sets off a teacher-response in adults just as adults set off a learner-response in children (this is stronger the younger the children are) (Lemke, 1995:160 [emphasis added]). 2 outline • Oral language development: orientations discouraging an interest in the adult role • Evidence from SFL case studies on the role of interaction and adult guidance • Reflections on interaction in literacy education 3 why does the ‘teaching’ role of the adult get effaced ? • the ‘nativist’ orientation from linguistics • Chomsky (LAD), Fodor, Bickerton (protolanguage), Gleitman (‘syntactic bootstrapping’, Hyams (parameters) Pinker (‘semantic bootstrapping’) – language is separate from cognition – grows and matures like any bodily organ – only role of environment is ‘triggering input’ for the innate ‘language acquisition device’ – mother tongue is impervious to teaching 4 MacNeill’s example Child: Nobody don't like me. Mother: No, say 'nobody likes me'. Child: Nobody don't like me. (Eight repetitions of this exchange) Mother: No, now listen carefully; say 'nobody likes me'. Child: Oh! Nobody don't likes me. McNeill, D. (1966 p.69) 5 “There is surprisingly little evidence that reinforcement, or indeed any sustained form of explicit teaching plays an important role in language learning. Indeed there exists some experimental evidence which suggests that explicit instruction in the child’s first language fails to be facilitating.” Foder, J.A, Bever, T.G. & Garret, M.F. The psychology of language 1974: 455 6 why does the ‘teaching’ role of the adult get effaced ? • the constructivist orientation from psychology Jean Piaget 1896-1980 - children construct their own knowledge from interaction and play with the material environment ‘discovery learning’ (cf Rousseau) - stage theory of cognitive development: ‘readiness’ is all “each time one prematurely teaches a child something he could have discovered for himself, the child is kept from inventing it and consequently from understanding it completely” (cited in PH Mussen (ed) (1970: 715) - language simply follows on from self-managed cognitive development - development is from ‘radical egocentrism’ to gradually becoming social 7 SFL 8 SFL case studies of first language development in the home Halliday, 1975 Learning how to Mean Nigel 0;9 – 2;9 Painter, 1984 Into the mother tongue Hal 0;9 – 2;9 Torr, 1997 From Child Tongue to Mother Tongue Anna 0;9 – 2;7 Painter, 1999 Learning through language in early childhood Stephen 2;7 – 5;0 Derewianka, B (2003) ‘Grammatical metaphor in the transition to adolescence.’ In Simon-Vandenbergen, A M et al (eds) Grammatical Metaphor: Views from Systemic Functional Linguistics Amsterdam / Philadelphia PA, Benjamins: 142-165 9 some recurring themes from SFL case studies • child is developing a resource for ‘making sense’ of experience (learning language while learning through language) • the child’s language follows a developmental trajectory: • protolanguage transition phase III (into language) • generalisation, abstraction, metaphor (with language) • child’s strategies for learning are ‘semantic strategies’ (cognition as meaning) 10 equally important “The learning of the mother tongue is also an interactive process. It takes the form of the continued exchange of meanings between the self and others. The act of meaning is a social act.” Halliday (1975:140/ 2004: 301) 11 drawing on… Human selves are born not as individuals but as sociable persons seeking other human selves … Trevarthen 2009: 511 in a (pre-linguistic) ‘proto-conversation’ Both actors, adult and infant …move together in dialogue, alternating and synchronizing moves to generate cycles of …address and reply… (Trevarthen 2009: 512) the mother’s voice “draws the infant consciousness into attentive focused states, leads to alternation of messages and leaves lasting impressions” Trevarthen 2009: 514) 12 1. baby Emma at 6 mo. M involves her in ‘clap handies’ game 2. boldly trying out on a new person… 3. … but when “uncomprehending, he responds with a sarcastic laugh” she lowers her head and eyes in a classic gesture of shame Trevarthen, C 1998:40 13 Halliday, 1980: the adult as ‘tracker’ “The caregivers not only exchange meanings with the child, they also construe the system along with him… [refers to Condon’s use of the term ‘tracking’ in relation to speakers’ monitoring each other’s contributions] …Now when we come to study the infant’s language development we find the concept of ‘tracking’ is fundamental here too. Not only do the caregivers track the process, [i.e. text] they also track the system. Child and adult share in the creation of language. The mother knows where the child has got to (subconsciously; she is not aware she has this knowledge, as a rule), because she is construing the system along with him; she brings it into play receptively, and stores it alongside her own more highly developed system -- which had been construed along similar lines in the first place” Halliday (1980/2004:199) ‘The contribution of developmental linguistics to the interpretation of language as system.’ 14 tracking is in order to interact and guide effectively 15 guiding into dialogue (1;1;15) (M switches light on) H: da! M: That’s the light, isn’t it? the light (1;2;0) M: Where’s the light? Where’s the light? (H looks at her intently, then up at light) M: It’s there, isn’t it? Where’s the light? H: dja (points at looks at light) M: Yes H: (points) da M: Yes, clever boy H: da; da; da; dja; da (points at another light) M: Mm, that one’s not on 16 guiding into dialogue the ‘standard action format’ (Ninio & Bruner, 1978) M: C: M: C M: C: M: C: M: Look! (attentional vocative) (touches picture) What are those? (query) (vocalises and smiles) Yes, they are rabbits (feedback and label) (vocalises, smiles, looks up at M) (laughs) Yes, rabbit (feedback and label) (vocalises, smiles) Yes (laughs) (feedback) cf Brown – the original word game; the ‘naming game’ 17 Theorised in terms of Vygotsky’s ideas and described as “scaffolding” “steps taken to reduce the degrees of freedom taken in carrying out some task so that the child can concentrate on the difficult skill she is in the process of acquiring” (Bruner, 1978: 19) here – attending to the picture, attending to the name, taking a dialogic turn 18 Lev Vygotsky 1896-1934 1934 Thought and Language 1962 Translated into English 1980s Beginnings of take-up in English speaking world – – language (and therefore social interaction) mediates cognitive development – learning takes place in the ‘zone of proximal development’ (ZPD) • region between learner’s level when performing solo in some task and the level that can be achieved under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers – the developmental trajectory is from ‘inter-mental’ (mediated by speech) to ‘intra-mental’ (contra Piaget) • “That which the child is able to do in collaboration today, he will be able to do independently tomorrow” (Vygotsky, 1978: 216-7 – learning in the ZPD is enabled by more expert others through ‘scaffolding’ (Wood, Bruner and Ross, 1976) and ‘guided participation’ (Rogoff, 1990) 19 scaffolding: the asymmetrical dyad 20 interacting with books (1;8; 11) (pushing an open picture book at M) H: Doing; doing (demanding tone) M: (puzzled at first) Oh; what’s he doing? Is that what I say? H: (beams) M: So, what’s he doing?... (2;1;23) (H looks at a picture book by himself) H: What’s that? (pointing at picture) -- Train -- No. What’s that? -- Tusk -- That’s right. TUSK! (2;1;23) history of shared experience allows adult to pass conversational ball back language comes to consciousness in process of being learned adult language gets appropriated – here at level of discourse 21 the ‘naming game’ continues 2;7;1 (M and S Looking at a picture book) DK1 K2 DK1 K2 K1 DK1 K2 K1 K1 K2f K1 K2f I R I R E/F I R E/F M: S: M: S: M: And do you remember what that is? Mm What is it? It’s a house It’s a house, special house. And what’s it made of? S: Oh (pause) snow. M: Yes, that’s right; It’s made of ice S: Made of ice M: And it’s called igloo. S: Igloo attentional query feedback and label query feedback and (‘recasting’ label) feedback with label shared experience: of the genre, involving typical ‘pedagogical’ exchanges 22 2;7;1 (M and S Looking at a picture book) DK1 K2 DK1 K2 K1 DK1 K2 K1 K1 K2f K1 K2f I R I R E/F I R E/F M: S: M: S: M: And do you remember what that is? Mm What is it? It’s a house It’s a house, special house. And what’s it made of? S: Oh (pause) snow. M: Yes, that’s right; It’s made of ice S: Made of ice M: And it’s called igloo. S: Igloo attentional query feedback and label query feedback and (‘recasting’ label) feedback with label shared experience: of the genre, involving typical ‘pedagogical’ exchanges of the text (do you remember?) 23 2;7;1 (M and S Looking at a picture book) DK1 K2 DK1 K2 K1 DK1 K2 K1 K1 K2f K1 K2f I R I R E/F I R E/F M: S: M: S: M: And do you remember what that is? Mm What is it? It’s a house It’s a house, special house. And what’s it made of? S: Oh (pause) snow. M: Yes, that’s right; It’s made of ice S: Made of ice M: And it’s called igloo. S: Igloo attentional query feedback and label query feedback and (‘recasting’ label) feedback with label shared experience: of the genre, involving typical ‘pedagogical’ exchanges of the text (do you remember?) adult talks about language it’s called… 24 2;7;1 (M and S Looking at a picture book) DK1 K2 DK1 K2 K1 DK1 K2 K1 K1 K2f K1 K2f I R I R E/F I R E/F M: S: M: S: M: And do you remember what that is? Mm What is it? It’s a house It’s a house, special house. And what’s it made of? S: Oh (pause) snow. M: Yes, that’s right; It’s made of ice S: Made of ice M: And it’s called igloo. S: Igloo attentional query feedback and label query feedback and (‘recasting’ label) feedback with label shared experience: of the genre, involving typical ‘pedagogical’ exchanges of the text (do you remember?) adult talks about language it’s called… adult offers new language for appropriation 25 2;8;29 S: Look Mummy baa baa black sheep M: Oh, that’s not a sheep, that’s a dog with a woolly coat. It’s called a poodle. Poodle. S: Oh, poodle (later) S: That’s not a lamb, no 26 SFL: the text – system relation • “…From acts of meaning children construe the system of language, while at the same time, from the system, they engender acts of meaning. When children learn language they are simultaneously processing text into language and activating language into text” (Halliday [1993] 2004: 341) 27 instantiation The relation between the meaning potential as a whole and the particular choices of meanings, wordings and soundings actualised in an individual text, on a specific occasion ‘system’ (potential) instance (text) ‘act of meaning’ 28 instances from which the child construes the system are jointly constructed What’s it made of? Oh. Snow Yes, that’s right, it’s made of ice Made of ice And it’s called igloo Igloo 29 In interaction: simultaneous creation of text and construal of system What’s it made of? Oh. Snow Yes, that’s right, it’s made of ice Made of ice And it’s called igloo Igloo ‘system’ (potential) instance (text) 30 the system (the climate)…[is] the pattern set up by the instances (the weather), and each instance, no matter how minutely, perturbs these probabilities and so changes the system (or keeps it as it is, which is just the limiting case of changing it. (Halliday 1992: 26/ 2002: 359) 31 scaffolding monologue on the basis of shared experience 32 Scaffolding stories (Nigel, around 1;9, recalling an outing with Mum) N: Bumblebee M: Where was the bumblebee? N: Bumblebee on train M: What did Mummy do? N: Mummy open window M: Where did the bumblebee go? N: Bumblebee flew away (Halliday, 1975: 99) Adult takes on burden of sequencing and structuring Child contributes events 33 (2;0) (H returns from shopping trip with F) H: Stick! M: (baffled) Stick, eh? H: Horse M: Oh, you’ve had a ride on a horse (a routine shopping mall event) H: Ride on horsey; ride on horsey ‘gain! adult ‘recasts’ child’s initiation to clarify it child extends meaning (2;1;24) (H has spent day with M) F: Where did you go today? H: To beach F: What did you do? adult scaffolds with relevant Q H: (silence) child responds and extends meaning M: Did you get wet? H: Yes, girl got all wet too. Crying 34 upping the ante Nigel: F: Nigel: F: Nigel: Try eat lid What tried to eat the lid? Try eat lid What tried to eat the lid? Goat… man said no… goat try eat lid… man said no (Later) Nigel: Goat try eat lid…man said no. M: Why did the man say no? Nigel: Goat shouldn’t eat lid (shaking his head no) good for it. M: The goat shouldn’t eat the lid. It’s not good for it Nigel: Goat try eat lid… man said no…goat shouldn’t eat lid (shaking his head] good for it (Halliday, 1975: 112) 35 So far… examples of adult scaffolding into dialogue (proto-conversations, protolanguage exchanges, shared observations) into the pedagogic genre of the naming game into monologue (recounts and anecdotes) all enabled by shared experience 36 The direction of adult guidance? 37 guiding the child to reflect on the meaning system 1. semantic categories 2;7;9 (talking about recent outing) S: That baby cry- crying M: Yes, it was; well babies do cry a lot when they’re little 2;7;3 S: That dog got a shaky tail M: Yes, dogs wag their tails when they’re happy 2;8;12 (M and S looking at a picture book about circus) S: Is that the clown? M: Yes; that’s the clown ‘cause he’s got a big red nose; clowns often have red noses 38 guiding the child to reflect on the meaning system 1. semantic categories 2;7;9 (talking about recent outing) S: That baby cry- crying M: Yes, it was; well babies do cry a lot when they’re little 2;7;3 S: That dog got a shaky tail M: Yes, dogs wag their tails when they’re happy 2;8;12 (M and S looking at a picture book about circus) S: Is that the clown? M: Yes; that’s the clown ‘cause he’s got a big red nose; clowns often have red noses the role of adult elaborating responses in making adult system ‘visible’ 39 that baby was crying Reference to tangible entity babies cry Reference to generic category unique e.g. Mary unique e.g. Mary specific e.g. that baby specific e.g. that baby generic e.g. babies child’s system being instantiated adult’s system being construed 40 Solo efforts a year later – reflecting on categories (3;7;5) (S talking to M about the ‘big shoes’ at the door) S: Hal has [big shoes] and you have and Daddy has; grown-ups have (i) self elaborations on adult model (3;8;1) M: …dogs are animals S: No, they aren’t; dogs aren’t animals M: Well, what’s an animal then? (ii) interactive explorations S: Um, giraffes are animals M: Oh, I see, you think animal is only for zoo animals S: Yeah (3;8;7) S looking at animal jigsaw puzzle pieces) S: There isn’t a fox [i.e. on jigsaw]; and there isn’t – is a platypus an animal? (3;8;14) M and H have been talking about dolphins being mammals) S: Are seals dolphins? M: No, but seals are mammals too; they aren’t fish 41 Guiding the child to reflect on the meaning system 2. using definitions 2;8;18 (S has been singing Mary had a little lamb) S: Fleece, not feece, no; not teece; not teece (laughing) M: No, not teeth F: (sings) Teeth were as white as snow S: No, not teeth, fleece M: Yes, fleece; fleece is the wool on the lamb. All the lamb’s soft wool is called the fleece S: (No response) 2;11;15 (S overhears the word pet in talk between M and brother) S: What’s a pet? M: A pet is an animal who lives in your house: Katy’s our pet. (later same day) S: What’s a pet called? 42 compare That is a pet Ref. to material entity = name/category ‘ostensive definition’ A pet name/category is = an animal who lives in your house category linguistic definition 43 Solo efforts a year later – reflecting on language (3;7;5) (S in bath about to be shampoo-ed) M: Put your head right back in the water (trying to get the hair wet). Come on, drown. S: Not drown!! Drown is go down to the bottom and be dead (3;7;8) (M and S enter house dripping wet with rain) M: (to F) Oh, we’re drowned! S: What does drown mean? M: Means we’re all wet (3;7;10) S: Maybe it’s going to sprinkler. You know what sprinkler means? It means little raindrops. And sometimes sprinkler is click on (?unclear); that means squirt at people (3;8;27) S: Ooh, listen! Look it’s- it’s hail. See the ice; you know, hail is balls of ice (3;10) (S bringing M a complex lego structure, carrying it gingerly) S: Balance means you hold it on your fingers and it doesn’t go on the floor 44 guiding the child to reflect on meaning as process 45 as processes of construal (inner semiosis) – seeing, knowing, thinking, remembering (2;7;1) (Bedtime book reading) M: Going to have this one first? D’you know what the name of this tiger is? He’s called (pause) Growl! S: Mm, Growl M [reads text]… ‘Your shadow” chuckled Trumpet Do you know what a shadow is? S: Mm M: You see my shadow, here on the book See that? See my hand? See the shadow of my hand. Shadow, fingers moving; see the fingers moving [reads on in text] M: The pond is like a mirror, you see And do you know what Growl was frightened of? He was frightened of his own face in the mirror, in the pond, his own reflection 46 (3;8;1) (M asks S if he knows a word in their book) S: No M: It’s an animal S: Rabbit? M: No, it’s ‘dog’ S: Dog’s not an animal! M: Yes it is… [further talk omitted] What is it, then? S: It’s- it’s just a dog M: Yes, but dogs are animals S: No, they aren’t; dogs aren’t animals M: Well, what’s an animal then? S: Um, giraffes are animals M: Oh, I see, you think animal is only for zoo animals S: Yeah M: Dogs are animals, too; they’re tame animals. And cats, cats are animals too. Did you know that? Bro: (chipping in) And people, were animals S: We’re not. 47 3;5;24 S: That’s for later [i.e. fruit] for porridge, if Daddy buys some more porridge M: If Daddy makes some porridge S: No, no, buy some porridge M: You buy the oats, you don’t buy the porridge S: Do you make porridge? M: Yes, you know that, you’ve seen Daddy make porridge S: Oh (pause) you put the muesli in, and all of it in and then let it go and then it turns into porridge 4;4;10 S: Hey, Mum, can dolphins eat boats? M: No S: Why? M: They don’t want to eat boats; they eat fish. Are you thinking of Pinocchio (recently seen movie)? S: Yes M: Oh, that was a whale. But they don’t really swallow boats. 48 as processes of verbalising (external semiosis) – say, tell (1;8;11) (pushing an open picture book at M) H: Doing; doing (demanding tone) M: (puzzled at first) Oh; what’s he doing? Is that what I say? H: (beams) M: So, what’s he doing?... 49 verbalising as semiotic identity relation (2;6;22) (M and S open a picture book) M: Hal wrote his name in this book. See, that says ‘Hal’ S: Hal; Hal’s book M: Yes, it was Hal’s book (2;7;3) (F hanging up S’s coat at kindy) F: There’s your peg; See (points at label) that says Stephen S: ‘S’ (pointing) ‘S’ (2;7;1) (S pointing at words in picture book) S: M: M: S: M: S: That’s same as Hal and that’s same as Daddy… and that’s Mummy I tell you what – this one is ‘sun’ there; see and this one says ‘snow’… That says eskimo Oh, eskimo And you know what that says? That one says whale Mm, whale (2;7;13) M: Here’s our Peter Rabbit book S: (points to random word) That says Peter Rabbit 50 symbols as meaning sources & Sayers in verbal processes 3;7;18 (M driving, in slow heavy traffic) M: Oh I’m going to get stuck behind this car now S: Why? M: He’s going to turn right S: Oh. Oh why’s he turning right? M: Well he’s blinking his light S: He (peering) he is blinking his light M: Yes, that – do you know what that means? that means that in a minute that car’s going to go that way (points) S: Are we going that way or that way? Are we going left or right? M: Straight on S: What does straight on mean? M: Means we’re not going to turn at all, see? … M: I can’t see his [indicator] light S: There! That light (pointing at brake light ahead) M: No, the red light- the red light tells you the car’s not moving; it’s the little yellow lights that tell you whether they’re gonna turn round or not… 51 later: adult models the written text as a meaning-making source 4;7;21 (reading a book about birds together) M: Look, he’s a starling and it says he has built his nest inside the eagle’s nest. Isn’t that strange? I didn’t know they did that… S: M: ….. M: S: M: …… S: M: S: What’s that? ….. Well, I’m just trying to read and see He flies about most of the year; this one’s flying over the sea. Even when it’s raining? I suppose so, yes, but it doesn’t tell you about that What-what is it trying to do? Oh it’s just – it’s had a bit of an accident I think, I suppose; well let me see if it tells youDoes it tell what he’s doing? 52 adult contribution as a resource 1a. for use ‘verbatim’ within the instance 2;8;29 S: Look Mummy baa baa black sheep M: Oh, that’s not a sheep, that’s a dog with a woolly coat. It’s called a poodle. Poodle. S: Oh, poodle (later) S: That’s not a lamb, no 4;7;21 M: it doesn’t tell you about that …… M: Well let me see if it tells youS: Does it tell what he’s doing? 53 “A piece of text is construed, and used appropriately, which includes lexicogrammatical and phonological features that have not yet been processed into the system. The system then catches up and goes ahead” (Halliday, [1980] 2003: 203) (4;8;30) F: S: This car can’t go as fast as ours. I thought- I thought all cars could- all cars could go the sameall cars could go the same (pause) fast. M: The same speed. S: Yes, same speed. 54 • The effect of this ongoing dialectic [of system and process] is a kind of leapfrogging movement: sometimes an instance will appear to be extending the system, sometimes to be lagging behind • A language is a system-text continuum, a meaning potential in which ready-coded instances of meaning are complemented by principles for coding what has not been meant before. (Halliday [1993] 2004: 341) 55 adult contribution as a resource 1b. for negotiation within the instance (learner recasts adult) (3;6;5) S: Mum, could you cry; could you cry or not? M: Yes, I could cry. S: How? M: What do you mean? If I hurt myself I might cry, same as you. S: If you fell down bump really really hard. (3;6;30 F and S in car talking about sports cars) F: And they go fast ‘cause they’ve got a big engine S: But that doesn’t go faster than us. (pointing) See? F: He’s not trying; if he was really trying he could go much faster than us S: If he goes very fast he can- if he goes very fast he can beat us 56 2) for storage and ‘re-use’ on future comparable occasions with original interactants (reversing roles) typical text age 2 M: Don’t you want any tea? Do you want some biscuits and cheese? H: No M: No? Not hungry. You’re not hungry tonight, eh? new feature (justifying a refusal) at 2;3 M: What a bit of toast? H: No thanks, I not hungry ( H pulling M & F by hands) H: Want to run again F: No, we can’t run any more; Daddy’s too tired and Mummy’s too tired M: Why don’t you get the little cars out? H: Mummy play cars; I can’t play cars; I’m too tired Adult models by ‘speaking for’ the child Child adopts discourse structure (justifying refusal) and specific excuse 57 2) for storage and ‘re-use’ on future comparable occasions with new interactants (3;5;20) (M warns S that he will crack his head if he’s not careful on the tiled floor) S: No, cause it’s got bone in see? (taps head) M: But bones can break. S: No, it’s hard. M: Yes, but if you bang your head on the hard floor, it can still break, the bones can smash. 3 days later (3;5;23) (M calls out to local children in street to be careful climbing the tree) M: The branches are not very strong S: And- and you can fall and your bones can SMASH 58 adult contribution as a resource 3. making visible new systemic options that ‘perturb’ the child’s system 2;7;9 (talking about recent outing) S: That baby cry- crying M: Yes, it was; well babies do cry a lot when they’re little 2;7;3 S: That dog got a shaky tail M: Yes, dogs wag their tails when they’re happy 2;8;12 (M and S looking at a picture book about circus) S: Is that the clown? M: Yes; that’s the clown ‘cause he’s got a big red nose; clowns often have red noses (3;7;5) (S talking to M about the ‘big shoes’ at the door) S: Hal has [big shoes] and you have and Daddy has; grown-ups have 59 Whichever path for the particular linguistic features, it has been made available to child through the co-created instance/s 60 Recurring interactional patterns 61 Focussing attention with meta-semiotic moves M: And do you know what Growl was frightened of? He was frightened of his own face in the mirror, in the pond, his own M: reflection And do you remember what that is? S: Mm Probing for extensions from the child (co-constructing monologue) Nigel: M: Goat try eat lid…man said no. Why did the man say no? Elaborating child’s contribution or adult response with additional K1 moves S: Made of ice. M: And it’s called igoo M: Don’t you want any tea? Do you want some biscuits and cheese? H: No M: No? Not hungry. You’re not hungry tonight, eh S: That dog got a shaky tail M: Yes, dogs wag their tails when they’re happy 62 Recasting the child’s contribution S: M: S: M: S: M: S: Why (?unclear) clouds and it does rain? Why does it rain? Why- why- there are clouds and it does start to rain and we don’t like it? Why does it rain when we don’t want it to? Mm I don’t know You have to tell something to me! (3;6;2) F: S: This [hired] car can’t go as fast as ours. I thought- I thought all cars could- all cars could go the sameall cars could go the same (pause) fast. M: The same speed. S: Yes, same speed. (4;8;30) 63 Clarifying the child’s contribution 3;5;7 (street near preschool) S: When they go to work, they leave their cars here. M: Who do? S: The peoples. M: The people at kindy? S: No, the people who goes to work. (?people’s) mummies. Challenging the child’s construals S: Look Mummy baa baa black sheep M: Oh, that’s not a sheep, that’s a dog with a woolly coat. It’s called a poodle. Poodle. S: Oh, poodle (later) S: That’s not a lamb, no ( 2;8;29) … via argument (M warns S that he will crack his head if he’s not careful on the tiled floor) S: No, cause it’s got bone in see? (taps head) M: But bones can break. S: No, it’s hard. M: Yes, but if you bang your head on the hard floor, it can still break, the bones can smash. (3;5;20) 64 oral language development at home • children learn their first language in interaction with guidance from a more expert user • shared experience (material and textual) is the basis of that guidance • adults guide through – sharing the semantic load in co-constructions – talking about semiosis – focusing attention, eliciting extensions, elaborating and recasting child’s contributions, clarifying and challenging the child’s construals, offering text for uptake (as text and/or systemic choice) 65 Interaction in formal literacy education? 66 1980s+ Re-evaluation of ‘transmission’ classroom methodologies in favour of progressivist, child centred ‘constructivist’ ideas ‘Traditional’ emphasis ‘Progressive’ emphasis didactic telling: ‘chalk and talk’ ‘child centred’ product process teaching subjects teaching students teacher as manager teacher as facilitator skills strategies This kind of dichotomising comparison alive and well in the 00s cf. Alexander, R Culture and Pedagogy: International Comparisons in Primary Education Oxford, Blackwell, 2000: 548 67 By 1990s explicitly Vygotskyan approaches as ‘social constructivism’ But in inviting contributions to Social Constructivist Teaching Brophy reports: “Some authors even expressed discomfort with the term ‘social constructivist teaching.’ They were more comfortable talking about learning and ways to support students’ construction of knowledge…” (Brophy, J. (ed) Social Constructivist Teaching: Affordances and Constraints 2002: xx-xxi) 68 Foregrounding interaction but eliding guidance… A Social Constructivist Model of Learning and Teaching as summarised in Wells, G (1999) Dialogic Enquiry 1.Creating a classroom community which shares a commitment to caring, collaboration, and a dialogic mode of making meaning. 2.Organizing the curriculum in terms… that encourage a willingness to wonder…and to collaborate with others in building knowledge 3.Negotiating goals that: 1. challenge students… 2. are sufficiently open-ended… 3. involve the whole person 4. provide opportunities to master the culture’s tools thru purposeful use 5. encourage group work and individual effort 6. give equal value to …processes and …products 4.Ensuring there are occasions for students to 1. use a variety of modes of representation… 2. present work to others and receive… feedback 3. reflect on what they have learned… 4. receive guidance and assistance in their ZPDs 69 Wells emphasises responding not guiding “a key feature of the [ideal] teacher role was that it was generally responsive rather than initiatory.” Wells 1999, p.300 An example of working in student’s ZPD (science class) (after children have been working with peers in small groups for an hour) T: Now.. did you make sure that [tape measure] was lined up at the starting? C: Um- (shakes her head) T: No, OK. Why don’t you start again then, cos that’s what you need to do… so erase what you did before, now you know how to do it. (Wells, G. Dialogic Enquiry: Towards a Sociocultural Practice and Theory of Education. 1999 p 303) 70 “It is better for a teacher to provide elaborations through instruction than to provide feedback on poorly understood concepts” Hattie, J A C (2009) Visible Learning: A synthesis of over 800 metaanalyses relating to achievement Routledge: London and NY 2009: 177 71 no asymmetrical dyad here!! “It is not so much a more capable other that is required as a willingness on the part of all participants to learn with and from each other” (Wells, G Dialogic Inquiry 1999 p.324) 72 Sydney School Genre Approach TLC based on SFL early case studies of language development implicit and explicit modelling of genre relevant content established and shared as part of writing process cultural purpose for writing always in foreground co-constructed model scribed and discussed in public Write it Right teaching/learning cycle (Rothery, 1994) 73 deconstruction phase More monologic: with attention focusing, scaffolded with metalanguage T: Ok. so she’s very clearly given her three Arguments. Can everyone see that? And the very interesting thing is that she lets you know in the introduction what those three Arguments are going to be. She hasn’t told you what they’re going to be; she’s just mentioned them… Can you see the difference? Because people started in that introduction going on to the Argument. You don’t [go into] it there; you only mention it. You don’t go into the … giving the reasons for the Argument. Can you see the difference? More dialogic: students take up on basis of that public sharing via IRF T: F: T: R: T: N: T: L: T OK. So there’s a few things to think about. What are some of the things I mentioned you are going to try to think abut when we do this one today? Filippa? Not to um, put an Argument into the Thesis Good. Right. Something else Don’t repeat yourself Don’t repeat Excellent. Something else. Who can think of something? Yes Don’t put any other ideas in the paragraph you are talking about. Good girl. Keep all the paragraph unified. Don’t start introducing new ideas into 74 the same one. Something else, to think about. Yes. The Argument that you’re doing has to be like he topic or Thesis that you choose Right. So you make sure you mentioned all your Arguments in your Thesis. Good. Organising ideas under teacher guidance for use in Joint Construction T: Right OK. Now lets try and get these into an order so we can organise how many paragraphs or how many new ideas we are going to introduce. Can someone sort of help me work that out? Who can see the main thing that keeps coming… the whole way through? Lisa? Lisa: Learn about a wide range of subjects T: Right. This seems to be one of the most important things, doesn’t it? So we can put say a ‘1’ next to it. Where else does it come up again? Lisa: Put that [pointing at notes] with the ‘1’ T: Right. So we can put ‘1’ against that- that could all be part of the same… paragraph then, couldn’t it? Somewhere else- the same sot of thing where we can link it together? Can you find any other links? Filippa? Fili: Use your education to get a good job T: Right. Now, would that be a new idea? Or is it the same do you think? … Remember that glue- trying to get that paragraph to stick together: We want to have a complete paragraph and then another complete paragraph. Do you think that one would work as a follow-up? After you’ve got your knowledge and you’ve applied all these skills, what are you going to be able to do there? S: Support your family T: Support your family by what? S: A job. T: A job. So that would really be another paragraph wouldn’t it?...... 75 jointly constructing Exposition text on the value of school education 2nd Argument in relation to whiteboard notes where points have been grouped by numbers 76 T: O.K. So, next paragraph. Let’s have a look. Who can start? Look at the number 2s now. What’s another good argument? Um, Safi? Um, um, Rana? S: It gives you an education to help you get a job and to work. T: Alright. Now, we really need to link that a little bit with the first paragraph. So what could we say? Secondly, by achieving this, what did we just achieve? Yes. T/Ss This knowledge. T: We will be then what? T/Ss Be in a better position to... to get a job. And to pursue our... careers. S: And support a family T: Secondly, after achieving this knowledge, it will then put all individuals who attend the school, in a position [some students reading along] O.K. So can you read that for me, Nicole? S: [reads text so far] T: Good. And what else? Can we develop that a little bit more? is there anything there that you can add to that from the board? Daad? S: And you can support your family or yourself from your job. T: Right. Um, so this will enable the individual to then support themselves or their... [unison] families. 77 explanation of recasting T: You noticed here I’ve used the word individual rather than say myself. I could say myself if I was writing it for myself, but considering I’m not, I’m writing for everyone, that’s why I’m using the word individual. If you were writing it, if you were trying to convince your audience, you could take two ways. If you used the word individual, it means everyone that ever goes to school, which is a stronger statement that if it’s just your own statement referring to... you. So, you have to think about that when you’re writing, think about who’s reading it and which is going to make the stronger statement. 78 Tertiary students: applied linguistics learning a text interpretation genre E.g. 1 T: Who can give me a topic sentence for this paragraph? S: ‘Speaking about participants, we can see that school kid and teacher are used the most often’ T: OK But let’s get rid of the ‘we can see’ because we’ve given part of the front of the clause there to ‘we can see.’ You can forget the ‘we can see’ and just go straight to what you want to say E.g. 2 T: S: T: So who can try to make a sentence for me that connects urbanisation with health issues, and which introduces us to positive and negative consequences, or something like that? Ah ‘a host of, ah, health needs can provide to the people in the cities.’ OK. But I’ll write ‘A host of health needs can be provided to people in cities.’ 79 E.g. 3 T: S: T: S: T: S: T: So can anyone suggest a sentence here? no response How about we start with the word ‘transitivity’ no response How about we start with the words ‘transitivity selections’ or ‘choices’ Transitivity selections tell us about the activity sequences and taxonomies that make up the field of education Beautiful! Cited in Martin & Dreyfus ‘Scaffolding semogenesis: designing teacher/student interactions for face-to-face and on-line learning’ in Starc (ed) (forthcoming) 80 How is this like earlier experience? 81 Co-construction of the exemplary instance is at the heart of the ‘natural’ language learning process Such instances – involve shared attention to and investment in the meanings negotiated – capitalise on shared experiences (textual and material) – involve an interactant with a more advanced meaning potential – capitalise on the learner’s capacity to reflect on and talk about meaning – involve elaborations and recastings of meanings made – enable the learner to appropriate and re-use ‘more advanced’ text – make ‘visible’ through text more advanced systemic options and realisations a written joint construction in a classroom, additionally - requires the teacher to be overtly conscious of the meaning potential to be made ‘visible’ in the co-instantiated text (planning!) - draws on publicly available scaffolds in the form of notes, lists, concept maps, generic staging labels … 82 going forward… Is the joint construction the part of the TLC least likely to be emulated? If so, why? Can co-constructions be more ‘designed’ so that they are maximally effective? (cf Rose’s Reading to Learn where exchanges constitute planned phases of: Identify^Prepare^Extend^Focus^Highlight) If talking about language is integral to language development, how effective can joint constructions be without investment in metalanguage beyond generic staging? 83 Articulating our theory of learning as a complementary theory of teaching - guidance through interaction - shared experience - explicit reflection on language 84 References Alexander, R Culture and Pedagogy: International Comparisons in Primary Education Oxford, Blackwell, 2000: 548 Applebee, A N and Langer, J A ‘Instructional Scaffolding: Reading and Writing as Natural Language Activities’ Language Arts 60.5: 168-175 Brophy, J. (ed) (2002) Social Constructivist Teaching: Affordances and Constraints (Advances in Research on Teaching v. 9) Amsterdam, New York, JAI/ Elsevier Science Bruner, J S (1978) ‘The role of dialogue in language acquisition.’ In Sinclair, A, Jarvella, R and Levelt, W J M (eds) The Child’s Conception of Language. NY, Springer Verlag Chomsky, N (1986) Knowledge of Language: Its Nature, Origin and Use. NY, Praeger Christie, F. and Derewianka, B (2008) Learning to Write across the Years of Schooling London & New York Derewianka, B (2003) ‘Grammatical metaphor in the transition to adolescence.’ In Simon-Vandenbergen, A M, Taverniers, M and Ravelli, L (eds) Grammatical Metaphor: Views from Systemic Functional Linguistics Amsterdam / Philadelphia PA, Benjamins: 142-165 Foder, J A, Bever, T G & Garret M F (1974) The psychology of language: An Introduction to Psycholinguistics and Generative Grammar. NY McGraw-Hill Halliday, M A K (1975) Learning How to Mean London, Arnold Halliday, M A K (1980) ‘The contribution of developmental linguistics to the interpretation of language as system.’ In Halliday, 2003: 197-209 85 Halliday, M A K (1992/ 2002) ‘How do you mean?’ In his On Grammar: Collected Works v.1 Ed. J Webster: 352-368 Halliday, M A K (1993/2004) ‘Towards a language based theory of learning.’ Linguistics and Education 5.2: 93-116 In His The Language of Early Childhood. Collected Works v.4 Ed. J Webster Halliday, M A K (2004) The Language of Early Childhood. Collected Works, v. 4. Ed. J Webster. London, Continuum. Hattie, JAC (2009) Visible Learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge: London and NY Lemke, J (1995) Textual Politics: Discourse and Social Dynamics. London, Taylor & Francis McNeil, D. (1966) ‘Developmental Psycholinguistics.’ The Genesis of Language: A Psycholinguistic Approach. Proceedings of a Conference on ‘Language Development in Children’. Ed. F. Smith and G. A. Miller. Cambridge MA, MIT Press Martin, J R and Dreyfus, S (forthcoming) ‘Scaffolding semogenesis: designing teacher/student interactions for face-to-face and on-line learning’ Ninio, A & Bruner, J 1978 ‘The achievement and antecedents of labeling.’ In Journal of Child Language 5: 36-49 Nuthall, G (2002) ‘Social Constructivist Teaching and the Shaping of Student’s Knowledge’ In Brophy (ed) 43-79 Painter, C (1984) Into the Mother Tongue London, Pinter Painter, C (1999) Learning Through Language in Early Childhood. London, Continuum 86 Piaget, J (1970) ‘Piaget’s theory.’ In Mussen, P H (ed) Carmichael’s Manual of Child Psychology. N Y, Wiley Rogoff, B. (1990) Apprenticeship in thinking. NY, Oxford UP Rothery, J 1994 Exploring Literacy in School English (Write it Right Resources for Literacy and Learning). Sydney: Metropolitan East Disadvantaged Schools Program. Torr, J. (1998) From Child Tongue to Mother Tongue: Language Development in the First Two and a half Years. (Monographs in Systemic Linguistics) Nottingham, Nottingham University Trevarthen, C (1998) ‘The concept and foundations of infant intersubjectivity.’ In S Braten (ed) Intersubjective Communication and Emotion in Early Ontogeny. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press Trevarthen, C (2009) ‘The Intersubjective Psychobiology of Human Meaning: Learning of Culture Depends on Interest for Co-operative Practical Work – and Affection for the Joyful Art of Good Company’. In Psychoanalytic Dialogues 19: 507-18 Vygotsky, L. 1987 Problems of General Psychology. His Collected Works v.1 tr. R.W. Rieber. NY, Plenum: 216-7 Wells, G (1999) Dialogic Enquiry: Towards a Sociocultural Practice and Theory of Education. 1999 Wood, D, Bruner, JS and Ross G (1976) ‘The role of tutoring in problem solving.’ Journal of Child Psychology and Child Psychiatry 17: 89-100 87