insanity_mso_06

advertisement

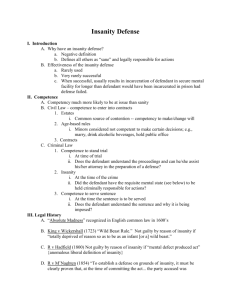

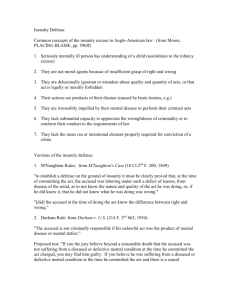

Insanity, MSO, and Related Issues Russell M. Bauer, Ph.D. July 27, 2006 Mental State at Offense • One of the most difficult and bloodcurdling tasks of a forensic psychologist – it is RETROSPECTIVE – MOTIVATIONAL factors affect current presentation • Requires “investigative reconstruction” of crime events, often involving information psychologists are not used to reviewing History of Insanity Defense • • • • Basic Concept: free will Mc’Naghten Case (1840’s) “Irresistable Impulse” rule Durham vs. United States: “product” of mental disease or defect (1954) • American Law Institute: appreciation vs. control • 1984 Congress: wrongfulness appreciation • VERY rare defense (<<l%, and of that, rarely successful) Pre-M’Naghten • 13th century: “man must be totally deprived of his understanding and memory so as not to know what he is doing, no more than an infant, brute or a wild beast” (Melton, 1997, p. 190). M’Naghten • 1843: murder of Prime Minister’s assistant • M’Naghten acquitted based on mental disorder • House of Lords later ruled: “To establish a defense on the ground of insanity, it must be clearly proved that, at the time of committing of the act, the party accused was laboring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act that he was doing, or, if he did know it, that he did not know what he was doing was wrong” • M’Naghten committed to Bedlam, eventually died in another hospital after decades of “treatment” Example • Defendant bites another person because he believes him to be a piece of chicken (crime: battery) – Could prove insanity under Prong 1 • Defendant bites another person, knowing him to be a person, but not knowing that biting is painful and can injure the other person – Could prove insanity under Prong 2 American Law Institute (ALI) • A person is not responsible for criminal conduct if at the time of such conduct as a result of mental disease or defect he lacks substantial capacity either to appreciate the wrongfulness of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the requirements of the law • Changes from before – Change implication of “full” to “substantial” – Change “know” to “appreciate” “Irresistable Impulse” • The defendant is not legally responsible: – if by reason of the duress of mental disease he had so far lost the power to choose between right and wrong, and to avoid doing the act in question that his free agency was destroyed – act the product of mental disease solely • Problem: how do you distinguish an “irresistable impulse” from an “impulse not resisted”? Three Variations on Irresistable Impulse • (l) Defendant 'acted from an irresistible and uncontrollable impulse'; • (2) Defendant 'lost the power to choose between the right and wrong, and to avoid doing the act in question, as that his free agency was at the time destroyed'; • (3) Defendant's 'will . . . has been otherwise than voluntarily so completely destroyed that his actions are not subject to it, but are beyond his control.' Durham v. United States • Source of the “product test” – simply that “an accused is not criminally responsible if his unlawful act was the product of a mental disease or defect” • Problems: – what is a “product”? (i.e., what is the causative chain?) – what is a mental disease? • Case eventually overturned; now of historical significance only State Interpretations • One-half use M’Naghten • One-third of states use ALI • Three states have reference to “irresistable impulse” • Four states have abolished insanity defense altogether (Montana, Idaho, Utah, Kansas) • NH: “product” of mental disease or defect Generally Excluded Mental Disorders • • • • Antisocial personality Adjustment disorder “Compulsive” disorders Seizure disorders allowable in some jurisdictions, not in others 1984 Congress (Insanity Reform Act) • Reform in response to Hinckley verdict • 1980’s ABA and APA standards: “A person is not responsible for criminal conduct if, at the time of such conduct, and as a result of mental disease or defect, that person was unable to appreciate the wrongfulness of their conduct” • 1984 Congress adopts ABA standard (cognitive prong of ALI) Unsuccessful Insanity Pleas • • • • • • • • • Kip Kinkel, l7, shot 29 people in an Oregon school rampage in 1998; heard “command” voices; abandoned insanity defense, got 25+ years David Berkowitz, “Son of Sam” killings NYC, sentenced to 365 years in jail Ted Bundy; US serial killer l974-l978; responsible for an estimated 40 murders; executed in FL electric chair Sirhan Sirhan: murdered Robert Kennedy l968; convicted, sentenced to death; commuted to life in prison Henry Lee Lucas; serial murderer in FL l982 Charles Manson; cult leader; sentenced to death; CA suspends death penalty later John Wayne Gacy, used DID defense; convicted of 33 murders in l980; executed l994 Ted Kaczynski, Unabomber, thought to be suffering from paranoid schizophrenia; 4 consecutive life sentences Jeffrey Dahmer; necrophilia, cannibalism, l60-page rambling confession; convicted l992, killed in prison l994 A notable exception • Andrea Yates: drowned children in bathtub; history of postpartum depression, convicted in 2003; conviction overturned on appeal, was found NGRI in second trial Issues in Insanity Defense • All variations require mental disease or defect • Applies most specifically to psychosis and mental retardation • Temporary vs. permanent insanity • Law does not distinguish conscious from unconscious reasoning • Meaning of the terms “know” and “wrong” • Irresistable Impluse: “officer at the elbow test” • Burden of Proof What the Jury is Told (CA) • • • • • The defendant has been found guilty of the crime of _____. You must now determine whether [he] [she] was legally sane or legally insane at the time of the commission of the crime. This is the only issue for you to determine in this proceeding. You may consider evidence of [his] [her] mental condition before, during and after the time of the commission of the crime, as tending to show the defendant's mental condition at the time the crime was committed. [Mental illness and mental abnormality, in whatever form they may appear, are not necessarily the same as legal insanity. A person may be mentally ill or mentally abnormal and yet not be legally insane]. A person is legally insane when by reason of mental disease or defect [he] [she] was incapable of knowing or understanding the nature and quality of [his] [her] act or incapable of distinguishing right from wrong at the time of the commission of the crime. The defendant has the burden of proving [his] [her] legal insanity at the time of the commission of the crime by a preponderance of the evidence. Burden of Proof • One-third of states require prosecution to prove sanity “beyond reasonable doubt” (90-95%) • Most remaining states require defendant to prove insanity by “preponderance of evidence” (5l%) • AZ and federal courts: defendant must prove sanity by “clear and convincing” evidence (75%) Basic Elements of Crime Behavior Relevant to Insanity Defense • physical conduct of crime (“actus reus”) • mental state (level of intent) associated with the crime (“mens rea”) • to convice beyond reasonable doubt, state must prove that the defendant committed the actus reus with the requisite mens rea for that crime Defenses Related to Sanity • Automatism Defense – acts committed “involuntarily” – this is different from sanity • automatons are “unaware” (but will be held responsible if ailment had previously existed and steps were not taken to prevent or manage it) • prosecution bears burden of negating automatism beyond reasonable doubt • no mental disease or defect required Defenses Related to Sanity • Diminished Capacity – mental state essentially defined culpability; planning a crime involves more intent than accidentally committing one – specific vs. general intent – Mens Rea components: • • • • Purpose: conscious intent Knowledge: awareness, but not conscious intent Recklessness: disregarding a substantial and unjustifiable risk Negligence: not aware of a risk, but should have been aware Defenses Related to Sanity • Intoxication - generally not viewed positively by the courts unless accidental • Guilty but Mentally Ill - may be sentenced to any term appropriate to the offense with the opportunity to receive treatment during the period of incarceration MSO Evaluation • Place emphasis on information related to crime scenario (contains mens rea information) • Statements/confessions are important, but must be treated with caution • Brief MSE (for diagnosis) • Discuss crime with defendant • Prior records relevant to diagnosis Phases of MSO Evaluation • • • • Review of Records Intro, orientation, rapport building Developmental/Sociocultural history Assessment of current mental status – May or may not require neuropsychological assessment – Should stage assessment relative to alleged behavioral shortcomings • Questions/descriptions of alleged crime