psych_insanity defense article_SR

advertisement

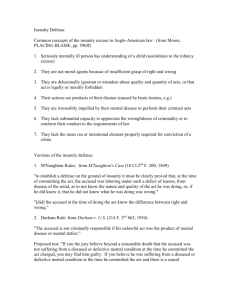

Insanity Defense When people defend themselves against criminal charges, they must refute one or more of the elements of the crime. If either the physical or mental elements of a crime cannot be proven, then the defendant cannot be convicted. Alibi defenses – you simply deny engaging in the crime. Excuse defenses – deny the mens rea. Cannot be held responsible for a crime because you did not have criminal intent—insanity, temporary insanity, post-pardum depression, battered woman syndrome, Twinkie defense. Justification defenses – deny the actus reus. Cannot be held responsible because you did not engage in an illegal act—self defense, duress, necessity, entrapment. (1) Defendant's state of mind excuses his criminal responsibility. A successful insanity defense results in a verdict of “not guilty by reason of insanity.” (2) Insanity is a legal concept, not a mental health term. It does not necessarily mean that persons using the defense are mentally ill or unbalanced, only that their state of mind at the time the crime was committed made it impossible for them to have the necessary intent to satisfy the legal definition of a crime. So a person can be diagnosed as a psychopath or psychotic but still be judged legally sane. Jeffrey Dahmer was found sane because Wisconsin used the “right-wrong test,” which requires that the defendant not know the difference between right and wrong. Dahmer said he knew what he was doing was wrong, but that he couldn’t control himself. It is usually left to psychiatric testimony in court to prove a defendant legally sane. Prosecutor must show that the defendant is sane by a preponderance of the evidence. (3) Person found legally insane at trial is placed in custody of state mental health authorities until diagnosed as sane. Sometimes, a person who was sane when he committed a crime becomes insane soon afterward. In that instance, the person receives psychiatric care until capable of standing trial on the criminal charge, since the person actually had mens rea at the time the crime was committed. On rare occasions, persons who were legally insane at the time they committed a crime become rational soon afterward (temporary insanity, post-pardum depression, battered woman syndrome, Twinkie defense). In that instance, the state can neither try them for the criminal offense nor have them committed to a mental health facility (Lorraine Bobbit). Tests for Determining Insanity The test used to determine whether a person is legally insane varies among jurisdictions. U.S. courts generally use either the M'Naghten Rule or the substantial capacity test. In 1843, an English court established the M'Naghten Rule, also known as the right-wrong test. Daniel M'Naghten, believing Edward Drummond to be Sir Robert Peel, the prime minister of Great Britain, shot and killed Drummond (Peel's secretary). At his trial for murder, M'Naghten claimed that he could not be held responsible for the murder because his delusions had caused him to act. The jury agreed with M'Naghten and found him NGRI. (1) M'Naghten Rule - defendant doesn’t know difference between right and wrong because of disease of the mind (called right-wrong test, used in Florida). A widely used test for legal insanity in the U.S. It is used in about half of the states. Over the years, there has been much criticism concerning M'Naghten. Great confusion has surfaced over such terms as disease of the mind and know right from wrong. These terms have never been properly clarified. Critics, mainly from the mental health profession, have pointed out that the rule is unrealistic and narrow in that it does not cover situations in which people know right from wrong but cannot control their actions. Because of questions about M'Naghten, approximately 15 states have supplemented the rule with another test, known as the irresistible impulse test. (2) Irresistible impulse test - defendant was unable to control his behavior because of mental disease. The defendant does not have to prove that he did not know the difference between right and wrong, only that he couldn’t control himself at the time of the crime. (3) Substantial capacity test - defendant lacks substantial capacity to appreciate wrongfulness of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the law. Created by the American Law Institute's MPC. It is essentially a combination of the M'Naghten Rule and the irresistible impulse test. It is broader in its interpretation of insanity because it requires only diminished capacity instead of complete impairment, as in M'Naghten and the irresistible impulse test. This test also differs in that it uses the term appreciate instead of know, the term used in M'Naghten. About half the states now use variations of the substantial capacity test. Insanity Defense Controversy The insanity defense has been the source of debate and controversy. (1) Critics believe defendant's psychological makeup should be raised at sentencing, not at trial. They argue that criminal responsibility is separate from mental illness. It is a serious mistake to consider criminal responsibility as a trait or quality that can be detected by a psychiatric evaluation. Some criminals avoid punishment because they are erroneously judged by psychiatrists to be mentally ill. Some people who are found NGRI because they suffer from a mild personality disturbance are incarcerated as mental patients far longer than they would have been imprisoned had they been convicted of a criminal offense. (2) Most successful insanity verdicts result in defendant being committed to mental institution until he has recovered. The insanity defense makes it possible to single out for special treatment certain persons who would otherwise be subjected to further sanctions following conviction. The insanity plea came into the spotlight when John Hinckley's unsuccessful attempt to kill President Ronald Reagan was captured by news cameras. Hinckley was found NGRI. Public outcry against this seeming miscarriage of justice prompted some states to revise their insanity statutes. (3) Some states created plea of guilty but mentally ill; defendant serves first part of sentence in hospital, once "cured" he’s sent to prison (being proposed for Florida). New Mexico, Georgia, Alaska, Delaware, Michigan, Illinois, and Indiana, among other states, have created the plea of guilty but mentally ill or guilty but insane (is no mens rea but guilty a contradiction?). (4) Some states shifted burden of proof from prosecutor’s need to prove sanity to defendant’s need to prove insanity (Florida). About 11 states (Florida) have followed the federal government's lead and made significant changes in their insanity defenses, such as shifting the burden of proof from prosecution to defense (by clear and convincing evidence). (5) In 1994, U.S. Supreme Court gave states right to abolish insanity defense (Cowan v. Montana). 3 states (Idaho, Montana, and Utah) no longer use evidence of mental illness as a defense in court, although psychological factors can influence sentencing. Although such backlash against the insanity plea is intended to close supposed legal loopholes allowing dangerous criminals to go free, the public's fear may be misplaced. (6) It is estimated the insanity plea is used in less than 1% of all cases. Evidence also shows that relatively few insanity defense pleas are successful. Even if the defense is successful, the offender must be placed in a secure psychiatric hospital or the psychiatric ward of a state prison. Since many defendants who successfully plead insanity are nonviolent offenders, it is possible that their hospital stay will be longer than the prison term they would have received had they been convicted of the original charge.