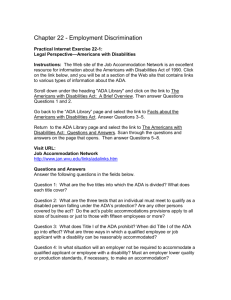

Chapter One, The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Magna Carta

advertisement