Domestic violence and child custody

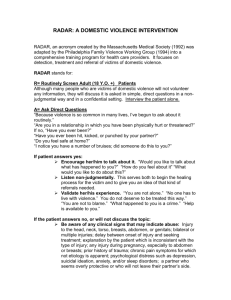

advertisement