3. earnings management - Erasmus University Thesis Repository

Equity Incentives and Earnings Management in the Banking Industry

The comparison between CFO incentives and CEO incentives

ERASMUS UNIVERSITEIT ROTTERDAM

Erasmus School of Economics

Master Thesis Accounting, Auditing & Control

Author: H.S. Wong

Student number: 196647

Thesis supervisor: Prof.dr.E.A. de Groot

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry

PREFACE

As a final assignment for the master course of Accounting, Auditing & Control at the Erasmus

University in Rotterdam, I was looking for a subject of current relevance for my master thesis. Due to the financial crisis of 2008 it was interesting to investigate the executive compensation in the banking sector. Writing a thesis is a long journey and I am glad I have finished it.

As a gesture of gratitude, I want to thank my master thesis supervisor prof. dr. E.A. de Groot for his help and guidance. Special thanks to my girlfriend and her sister for their support, advice and criticism. Their feedback was very helpful in order to maintain a logical structure and relevance.

Finally I want to thank my family for their encouragement and their support for writing this master thesis.

Hosan Wong

The Hague, March 2011

1

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry

ABSTRACT

This research investigates the association between CFO equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry compared with the CEO. Based on banks in the United States and executive compensation data for the period 1998-2008, I used the provisions for loan losses as proxy for earnings management. In testing the hypotheses I divided the sample in a pre- and post-SOX period.

Evidence shows that equity incentives of CEO and CFO are positively related to use of discretionary loan loss provisions in the pre-SOX period. After the introduction of SOX no association was found for CEO equity incentives and earnings management. A lower but still positive association remained for CFO equity incentives and earnings management in the post-SOX period. The impact of CEO equity incentives dominates that of the CFO in pre-SOX and the opposite is found for the post-SOX period. Additionally, it can be concluded that the intention of SOX to mitigate earnings management has been fulfilled for the banking industry.

Keywords: Equity incentives; Earnings management; Banking industry; Sarbanes-Oxley Act; CFO

2

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry

TABLE OF CONTENTS

3

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry

APPENDIX 2: SUMMARY OF PRIOR EMPIRICAL LITERATURE ........................................ 57

4

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

The financial crisis of 2008 has brought the attention to the banking industry with regard to the bonus payment and excessive compensation of executives. While banks take huge losses and their stock prices drop drastically, the bonus payments of bank managers haven’t been diminished with the same impact. These bonus compensations and excessive greed are being criticized by politicians and the media. As a result, scrutiny on executives’ compensation has intensified as banks prepared to pay out bonuses even after they have received billions of dollars of taxpayers’ money (Story 2008). The use of stock option compensation has increased rapidly over the years and now comprises a large portion of the total compensation package. The excessive salaries of managers are driven by relating compensation to firm performance and the rewards of stock options. This large package of equitybased compensation can induce managers to engage earnings management practices in the hope of increasing their firm’s share price. After managing earnings successfully, they are likely to sell their options and shares in order to maximize their salary at the cost of creating firm value.

Previous studies have examined the relation between executive’s equity incentives and earnings management. For example, Bergstresser and Philippon (2006) found a positive relationship between executive equity incentive and earnings management. They found evidence that more incentivized chief executive officers (CEO) are associated with higher levels of earnings management and there are unusual option exercises and share sales by CEOs in periods of high accruals. Next to it, Cheng and

Warfield (2005) documented that managers with high equity incentives sell more shares in the year after earnings announcements and are more likely to report earnings that meet or just beat analysts’ forecasts. Cornett, Marcus and Tehranian (2007) found that stock options as compensation increases earnings management and reduce the quality of earnings, but they pointed out that earnings management can be mitigated by using governance mechanisms and more monitoring. In addition,

Cheng, Warfield and Ye (2009) found evidence in the banking industry that CEOs with high equity incentives only engage earnings management when capital ratios are close to the minimal capital requirements of regulators.

The focus in these studies has been mainly on the CEO. This is likely, because CEOs receive the largest compensation package and the CEO is believed to be the most influential. Nevertheless, Jiang,

Petroni and Wang (2010) have examined the relationship between equity incentives of the chief financial officer (CFO) and earnings management in industrial firms. Their evidence shows that equity incentives induce the CFO more to engage earnings management relative to the CEO. For earnings management studies, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX) is an important event which requires both CEO and CFO to certify that there are no material weaknesses in the financial statements. A

5

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry recent disclosure requirement of the Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) is an important event for executive compensation, because the SEC mandates firms to add additional disclosure of information about CFO compensation and claim that CFO compensation is important to the shareholders as well. It is therefore interesting to examine equity incentives of the CFO.

Moreover, SOX seems to have a large impact on earnings management behavior. Regulators implemented SOX to set a higher standard on the quality of financial information and state specifically that generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) can no longer be used as a defense against charges of malicious earnings management practices. It is expected that SOX will reduce earnings management practices (McEnroe, 2007). Cohen, Dey and Lys (2008) documented an increasing use of accrual-based earnings management in the pre-SOX periods, but it has been substituted by real earnings management in the post-SOX period. Therefore, this research will attempt to provide evidence on the association of CFO equity incentives and earnings management in comparison with

CEO during the pre-SOX and post-SOX period. Next to it, prior studies often exclude financial firms in the sample because of differences in regulations and accrual processes. Therefore, this paper will investigate the extent of earnings management in the banking industry. The financial crisis of 2008 has shown that banks are critical components of the economy and have significant influence on the financial market worldwide.

1.2 Problem statement

In order to investigate the effect of CFO equity incentives on earnings management relative to the

CEO in the banking industry, the research question will be formulated as follows:

“What is the association between CFO equity incentives and earnings management relative to the association of CEO equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry?”

The following sub questions will be investigated and used in order to answer the research question:

1.

What are equity incentives?

2.

What is earnings management?

3.

What is the general relation between equity incentives and earnings management?

4.

What research design can be developed to measure equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry?

1.3 Methodology

This paper uses the Positive Accounting Theory, which describes and explains the accounting practices and predict accounting behavior using empirical evidence. First I present the theoretical

6

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry background of earning management and equity incentives, which influence the choice of managers in selecting particular accounting methods. In the second part I will develop hypotheses to predict the outcome of the main research question using empirical research. Like prior studies I will examine loan loss provisions (LLPs) as tool for earnings management in the banking industry. LLPs are relatively large accruals and therefore have significant influence on earnings (Ahmed, Takeda and Thomas,

1999). To detect earnings management I will use the model from Beaver and Engel (1996) to decompose LLPs into nondiscretionary and discretionary components. The discretionary component of LLP is used as the proxy for earnings management. The final sample consists of commercial banks in the U.S. in the period 1998-2008. I will divide this period in a 1998-2001 pre-SOX period and a

2002-2008 post-SOX period, because it is interesting to investigate whether the implementation of

SOX in 2002 has resulted in reducing the effect that equity incentives have on earnings management practices. Equity incentives are measured using executive compensation data, which are obtained from the Execucomp database. The data for measuring earnings management in the banking industry are collected from Compustat Banks and the Bankscope database.

1.4 Structure

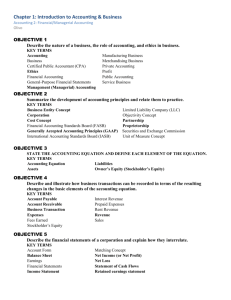

Chapter 2 explains equity incentives of the compensation contract. I will use the agency problem to provide a theoretical framework. Next, the need for equity incentives is explained, followed by equity incentives in the banking industry. Chapter 3 starts with an overview on earnings management, following by the importance of earnings and accrual accounting. Then, the definitions, motives and methods to detect earning management will be documented. Because the banking industry has different motivations and different accruals to apply earnings management, they are described separately in the last section. Chapter 4 presents prior literature about the relationship between equity incentives and earnings management. Furthermore, the studies about the consequences of SOX on earnings management are discussed. Thereafter, in chapter 5 the hypotheses are developed. Chapter 6 presents the research design and the sample selection. In chapter 7 the data will be analyzed and the results will be reported. Moreover, the results are used to test the hypotheses. Chapter 8 presents the conclusions and the findings are compared with prior studies. Additionally, the limitations of this research and suggestions for further research will be discussed.

7

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry

2. EQUITY INCENTIVES

In this chapter I will use the agency theory to clarify equity incentives within the managers’ compensation contracts. Paragraph 2.1 describes equity incentives. Paragraph 2.2 discusses the urge to use equity incentives. Paragraph 2.3 explains the setting and the disclosure of executive compensation.

Paragraph 2.4 discusses the manipulative behavior of managers due to variable compensation. Equity incentives in the banking industry are explained in paragraph 2.5. A summery and conclusion will be given at the end of this chapter.

2.1 What are equity incentives?

Equity incentives are motivations arising from stock-based compensation and stock/option ownership, encouraging managers to increase the firm’s share price. Murphy (1999) documented that executive compensation packages contain four basic elements: base salary, annual bonus ties to accounting performance, stocks and option plans. Over the years, stock and option compensations make up the largest segment of the CEO package. Stock rewards are granted in different kinds, such as: normal stock grants; and restricted stock grants, which cannot be sold within specific time or before the firm reaches a performance goal (Ronen and Yaari, 2009, p. 81). Stocks enable managers to be part of the firm’s ownership.

Options are contracts which give the holder the right to buy a certain share of stock at a pre-specified exercise price. The exercised option is only profitable when the share price is higher than the exercise price, also referred as “in the money”. Murphy (1999) mentioned that options don’t give the same incentives as stock ownership for several reasons: (1) executives holding options have incentives to avoid dividends and favor share repurchases, because options reward only when the stock-price increases and not shareholder returns; (2) options induces executives to take riskier strategies to increase firm value, because then the manager will make a gain of the difference between share price and exercise price times the number of shares; and (3) options lose incentives when they are not “in the money”. Feltham and Wu (2001) argue that a unit of stock is equivalent to an option with a zero exercise price.

2.2 Why are managers given equity incentives?

The purpose of equity incentives is to align managers’ interest with that of shareholders and to encourage risk-averse managers to increase firm value by taking more risk. Jensen and Murphy (1990) indicated that CEOs in the period from 1974 till 1986 only saw a $3 increase in the value of their stock and option portfolios for every $1,000 increase in shareholder wealth. They suggested that CEOs had little incentive to maximize shareholder value. Equity based compensation is therefore used to give executives a greater incentive to act in the interests of shareholders. In firms where there is a

8

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry separation of ownership and control there is a need to align the managers’ interest with that of the shareholders. The agency theory assumes that managers are driven by self-interest and act opportunistically. Managers in possession of control over a corporation, especially the CEO, can extract private benefits of control at the expense of shareholders. This may lead to lesser firm value and the incurred losses are called agency costs (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). An example is the CEO of Tyco, who purchased products for private use for over the $2 million with company funds (Heisler,

2007). Since the manager runs the firm instead of the shareholders, the manager will gain more knowledge about the firm. The information asymmetry causes efficiency loss and agency costs, because the manager may use his superior information about the firm to pursue his own interest at the expense of the shareholders. This information asymmetry, on top of self-interest, induces managers with equity incentives to engage opportunistic behavior and increase their own wealth at the expense of shareholders’ wealth.

Nonetheless, the agency theory postulates that shareholders expect their agents to take opportunistic actions and decrease the value of the firm (Deegan and Unerman, 2006, p. 224). In the absent of controls mechanisms, shareholders will therefore pay their agent a lower salary to compensate for the expected disadvantage behavior. This causes the manager to incur some costs for his expected behavior. However, the manager may derive greater satisfaction from extra salary than from the perks that they are predicted to consume. In that case, the manager is better off by signing a compensation contract agreeing not to consume company’s resources against a higher payment and shareholders can reduce agency costs. The set of available actions will decrease when the manager binds himself with a compensation contract. To ensure the manager complies with his contractual agreement, monitoring activities are needed. These activities results into bonding and monitoring costs, which are to guarantee that the agent keeps up to the contractual agreement. There is also a “residual loss”, because monitoring and bonding activities can’t mitigate the agency cost completely (Jensen and Meckling,

1976).

Furthermore, the compensation contract is designed to encourage the manager to put effort in increasing firm value. When the compensation package only consists of a fixed base salary, then the self-interest manager won’t take great risks since there is no share of any potential gains. Also, the relation between shareholder and manager is characterized by moral hazard, which means that they don’t share the same risks. Since the manager bears no risk at all, it limits the incentive for the manager to adopt strategies that increase the value of the firm. They will act like debt-holders by protecting their fixed income from any risky projects (Deegan and Unerman, 2006, p. 225). Therefore, variable components like stock and options in the compensation packages are necessary to tie the manager’s reward to the performance of the firm giving managers incentives to increase the share price. An increased share price benefits both the manager and shareholders.

9

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry

2.3 The setting and disclosure of compensation

The board of directors is responsible for monitoring management on behalf of shareholders. It has the power to hire and fire the CEO, set his compensation, supervise their actions, provide advice and block poor decisions (Prowse, 1995, p. 13). However, in the U.S. the CEO has some significant influence on the board’s decision making. Since stock ownerships are too diffused to give enough voting rights to select board members, the board is often chosen by the CEO instead. Additionally, the

CEO is also frequently the chairman of the board bringing the CEO much power. To balance this power, outside directors are selected to board as a controlling element. Peculiarly, the CEO has also influence in selecting outside directors and the objectivity of outside directors can be questioned when they have financial interest in being a board member. Since the board sets the CEO’s compensation contract and the board is under the influence by that manager, he might be paid beyond optimal level.

It gives the manager the opportunity to take unanticipated actions that increase the value of his shares and options by increasing the volatility of the firm’s performance or reduce his risk by smoothing earnings (Ronen and Yaari, 2008, p. 63).

Over the years executive compensation has changed but disclosure rules have not. The inability to get detailed information about executive compensation package has been heavily criticized. Therefore, investors urged the Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) to mandate companies in disclosing detailed, clear and in plain English information about executive compensation package and the process of its establishment. In 2006, the SEC adopted extensive changes to the rules of executive compensation disclosure. An important addition is the Compensation Discussion & Analysis (CD&A), which provides an overview why certain levels of compensation are selected and how it is justified.

More specific, the CD&A explains and provides analysis of the company’s compensation goals, practices and decisions for the CEO, CFO and three other highest paid executives and directors

(Council of Institutional Investors).

2.4 Equity incentives and earnings manipulation

Goldman and Slezak (2006) argued that stock-based compensation acts like a double edged sword. On the one hand, relating managers’ compensation to share price movement induces beneficial effort to increase firm performance and firm value. On the other hand, it induces managers to divert valuable firm resources and misrepresent performance. Kedia (2003) noticed that the increasing proportion of

CEO compensation containing stock options and shares makes the manager’s personal wealth more sensitive to the share price.

This increased pay for performance sensitivity can give executives opportunistic incentives to increase the share price regardless of the consequences on firm value. One method for managers to maximize their compensation is earnings management, where aggressive accounting is used to inflate share prices by reporting performance numbers that do not reflect the

10

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry firm’s underlying value. Gao and Shrieves (2002) showed that, in contrast to base salary, the amount of stock options and bonuses are positively related to earnings management intensity. Bergstresser and

Philippon (2006) stated that equity incentives have “… the perverse effect of encouraging managers to exploit their discretion in reporting earnings, with an eye to manipulating the stock prices of their company.”

According to Ronen and Yaari (2009, p. 84) equity-based compensation provides conflicting incentives to manage earnings. A higher share price increases the value of one’s stock and option holdings. This will lead to a short-horizon earnings management, where inflating earnings is optimal.

However, the higher the market price, the harder it gets to earn a raise in the future. This gives another incentive to go for long-horizon earnings management, aimed at deflating or smoothing earnings.

Nevertheless, the accounting literature expects that equity-based compensation gives incentives for a limited horizon. Since the average tenure of a CEO in a corporate firm is around 4 years, managers seek to ensure increasing short-term stock prices (O’Connell, 2004, cited from Ronen and Yaari, 2009, p.84). This is in line with Graham et al. (2005, p.65), who pointed out that managers are focused on short-term earnings benchmarks, particularly the lagged quarterly earnings number and meeting and beating analysts’ forecast.

Cheng and Warfield (2005, p. 445) noted that holding shares and options exposes the managers to the idiosyncratic risk of the firm, and they are more likely to sell their shares to reduce this risk The exposure of risk increases in the future when stock prices increase, because a large portion of manager’s wealth has become sensitive on short-term stock prices and risky option holdings. To diversify this increased risk, incentives for earnings management may arise. Managers who sell shares in the future engage earnings management when two conditions are met: (i) the capital market use reported earnings to predict future earnings, giving earnings management a purpose to affect stock prices and (ii) managers can benefit from increased stock prices. Taking both conditions as true, the manager will gain more from selling shares when earnings management is used to increase stock prices than without using earnings management. Moreover, Cheng et al. (2009) pointed out that when management sells their granted shares or exercises their options, the ownership benefits will diminish and the purpose of aligning interest and increasing firm value will be nullified.

2.5 Equity-based compensation in banks

It is argued that bank directors need less equity-based compensation. Regulated firms are more transparent and their opportunities to invest in projects are limited. Houston and James (1995) found little evidence that compensation contracts in banks are designed to encourage excessive risk taking.

The remuneration that bank managers receive consists of less cash salary as well as fewer equity based

11

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry compensation, meaning that bank CEOs are paid less equity-based compensation than non-bank

CEOs. This may imply that the moral hazard problem might be less severe and that the nature of the banks’ assets and investment opportunity sets mitigate the agency problems. Therefore, attempts by regulators to control compensation in banks are likely ineffective, since there are no incentives for excessive risk taking. Adams and Mehran (2003, p. 131) showed that increased use of stock options in executive compensation also holds for public banks, while the growth and amount of stock options used in banks are lower than in nonbanks. They also mentioned that it is easier for the board to monitor CEOs in low-growth industries (e.g. banks) than companies with high-growth opportunities; therefore more fixed compensation is used rather than stock-based compensation.

However, equity-based compensation in banks has changed over time. Becher, Campbell II and Frye

(2005) examined equity-based compensation during the period 1992-1999. Due to deregulation, banks face similar business environments as nonbanks. They noted that in the beginning of the 1990s significantly less equity-based compensation was used and with a slower rate than nonbanks. This amount changed after deregulation and banks use equity-based compensation at similar rates as nonbanks by the end of the 1990s. The effect was that differences in equity incentives in banks and nonbanks disappeared, while banks using a high degree of equity compensation are associated with higher performance and growth without increased risk. Cuñat and Guadalupe (2009) found the same results. They pointed out that total pay remained constant or have slightly increased, but there is a strong difference between fixed pay and variable pay. They find substantial evidence of reduced fixed pay and increased pay performance sensitivity, indicating that deregulation and more competition leads to greater use of incentives for bank managers to increase firm performance.

2.6 Summery and conclusion

Agency problems exist when there is a separation of ownership and control in firms. Equity incentives, classified as options and stocks, are given to mitigate the agency problems. Options encourage managers to be less risk-averse and adopt strategies to increase firm value; and shares enable them to become owners and thereby reduce agency costs. Also, it gives the incentive to management to maximize the value of their shares, for better alignment with shareholders’ interest.

The board of directors is responsible for the oversight, monitoring and setting the compensation contract of the executive director. The design of the compensation contract is used for bonding the director, giving him incentives to perform within the interests of shareholders. However, higher equity incentives may lead to use of earnings management to manipulate short-term stock prices. In the banking industry they relied less on equity-based compensation because there was no need to encourage excessive risks taking strategies. After the introduction of deregulation and competition in banks, the use of option and stock compensation has increased to similar levels of compensation package designs in nonbanks. In the following chapter earnings management will be discussed.

12

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry

3. EARNINGS MANAGEMENT

This chapter starts with defining earnings management. Paragraph 3.2 describes the accrual-based method of earnings management. Paragraph 3.3 explains why earnings are being the main target of manipulation. The motives for firms and managers to apply earnings management is documented in paragraph 3.4. The frequently used models to detect earnings management are addressed in paragraph

3.5. Specific motivations and model to detect earnings management in the banking industry are explained in the subsequent paragraphs. The chapter ends with a summery and conclusion.

3

.1 Earnings management defined

Generally, earnings management is a practice using a particular accounting method to manipulate earning numbers in a certain direction. A frequently used definition in the literature for earnings management is of Healy and Wahlen (1999, p. 368): “ Earnings management occurs when managers use judgment in financial reporting and in structuring transactions to alter financial reports to either mislead some stakeholders about underlying economic performance of the company or to influence contractual outcomes that depend on reported accounting numbers.”

Another definition is from Schipper (1989, p. 92) she defines it as

“in the sense of a purposeful intervention in the external financial reporting process, with the intent of obtaining some private gain.”

These definitions have a negative view on earnings management by suggesting it as misleading and to obtain private gain. Misleading earnings management distorts the truth and is a result of poor governance, but manipulates reports within the boundaries of the accounting standards. Opportunistic earnings management maximizes managers’ wealth instead of firm value. When earnings management misrepresents or reduces transparency of financial reports and violating the generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), it is called fraud.

However not all earnings management is misleading and opportunistic. Some investors prefer to separate continual earnings from short term shocks. When conserving low volatility in net income, also referred as earnings smoothing, the financial report will show a more accurate picture of the firm’s performance over the long-term period (Ronen and Yaari, 2008). McKee (2005, cited from

Grasso et al. 2009) considers earnings management as beneficial and defines it as "reasonable and legal management decision making and reporting intended to achieve stable and predictable financial results." Beneficial earnings management uses the flexibility in accounting methods to reflect the manager’s inside information on future cash flow. Flexibility implies the possibility to adjust accounting information within the opportunities given by the accounting standards. Also, it improves

13

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry the transparency on financial reports, because the manager uses his knowledge to present a more accurate financial position of the firm and reduces the information asymmetry between management and shareholders. Efficiency enhancing earnings management maximizes the firm’s value.

3.2 Accrual accounting

Earnings management can be applied using operational or accounting manipulation. Operational manipulation, also named real earnings management, affects the timing or selection of actual business events, such as giving discount to customers to increase sales. Grasso et al. (2009, p. 2) documented that managers apply real earnings management when deviating from the first best practice to achieve a desired result of increased reported earnings, rather than to satisfy customers or to achieve long term performance and strategic goals.

Accounting manipulation uses accruals to manage earnings by choosing certain accounting methods.

Healy (1985, p. 86) defines accruals as

“the difference between reported earnings and cash flow from operations.” Operating cash flows are cash received from customers and cash paid to suppliers and employees, but not cash from not financing or investing activities (Deloitte IAS Plus). Accruals include depreciations and amortizations, changes in working capital, extraordinary losses and changes in provision, which need manager’s judgment to value them. The primary motivation behind accrualbased earnings management is to achieve a desired result on reported earnings in a period rather than to present accurately the value of assets and liabilities or the results of operations.

Manipulating earnings using accruals is made possible because accrual accounting requires judgment and assumptions. Moreover, accrual-based earnings management is widely applied, mainly because firms prefer using accrual accounting for financial reports rather than cash accounting. Since cash accounting recognizes transactions only when there is an exchange of cash and doesn’t take future cash (e.g. sales on credit) into account, it cannot report the full economic consequence of the transactions in a given period. Accrual accounting, on the other hand, distinguishes between the recording of costs and revenues associated with economic events and the actual cash transactions. It enables firms to accurately present financial reports on a periodic basis and provide a better administration for the increasing complexity of business transactions. This accuracy is due to the possibility of combining current cash flows with future expected cash flows. However, the future cash flow relies on expectations, that’s why accrual accounting is subjective and based on assumptions

(Palepu et al. 2007, p. 6-7). Managers are entrusted with this accounting discretion to make proper assumptions and accurately reflect the inside information in financial statements. Additionally, it gives managers the flexibility to alter accounting earnings. While the performances are measured by earnings, managers may use their discretion making biased assumptions on future cash flows. It allows

14

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry them to increase their performances by increasing earnings. When management opportunistically manipulates accruals, earnings will be less reliable to measure performance.

3.3 Importance of earnings

Why are earnings manipulated in the first place? Earnings are widely believed to be the main information item provided in financial statements (Lev, 1989, p. 155). Investors need informative data to predict the future cash flow and risks of firms, before making decisions. In the accounting history the usefulness of earnings has been examined frequently. For example, Ball and Brown (1968) examined for stock market reactions on accounting earnings announcements and found evidence that earnings announcements impacts share prices. Moreover, Ronen and Yaari (2008, p. 8) present three approaches to highlight earning’s informativeness:

The costly-contracting approach: Every transaction the firm makes involves making a contract to prevent conflicting interest among contracting parties, for example a compensation or a debt contract. However, it is impossible to design a truly complete contract. There are unforeseen contingencies in the future and opportunistic behavior of either party. Adjusting badly designed contracts is costly. Therefore, earnings are needed to provide better measurement of future contingencies and to design efficient contracts. When unforeseen contingencies do happen and contracts cannot be adjusted, firms or executives may manage earnings to achieve their goals.

The decision-making approach: The firm’s output is determined by the interactions from many decisions makers, who settle their relationships through contracts. Any accounting number that provides relevant information is valuable for decision making. This approach assumes that decision makers are not fully informed. They need earnings to provide them valuable information to estimate future earnings for the contracting process.

The legal-political approach: Shareholders are in contrast less protected than other stakeholders. They don’t possess the knowledge to set managers’ compensation, nor can design contracts that prevent managers enriching themselves at their expense. The fact that shareholders are less knowledgeable about the firm’s business makes accounting information more valuable. Demanding proprietary information will be too costly and cumbersome, besides it might get exposed to competitors. Therefore, earnings are the summary information for shareholders without requiring them to learn the firms operation in detail.

3.4 Motives for earnings management

Since earnings contain useful information, it can be abused to affect the possibility of wealth transfer between the relationship of company and managers, funds providers or society (Stolowy and Breton,

2004, p. 3). Positive Accounting Theory (PAT) translates these relationships respectively into three

15

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry key hypotheses: bonus plan hypothesis, debt/equity hypothesis and political cost hypothesis (Watts and Zimmerman, 1978). However, Graham et al. (2005) used a survey investigation on earnings management motivations of chief financial officers (CFO) and didn’t find much evidence for traditional incentives like the political cost or debt/equity hypothesis. Their findings confirm that earnings are the main metric for stakeholders and not cash flow. They found that CFOs have strong preferences to smooth earnings. Because low volatility is associated as less risky by investors, smoothed earnings will have an increasing effect on stock price. Also, CFOs prefer making small to moderate sacrifices of economic value (i.e. real earnings management) to smooth earnings, instead of within-GAAP accounting adjustments. Cohen et al. (2008) found out that real earnings management as substitute for accrual-based earnings management is a consequence of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act.

Furthermore, it is important to meet or beat earnings benchmarks of analysts and last year’s earnings because it enables CFOs to (1) build credibility with the capital market; (2) maintain or increase stock price; (3) improve external reputation; and (4) convey future growth prospects. Missing earnings benchmarks creates uncertainty and suggests that firms hide more bad news. CEOs and CFOs know that the capital market will punish the firm when they don’t meet the analysts’ forecasts.

According to Graham et al (2005), the relevant motives for earnings management are: the bonus plan hypothesis, capital market, company efficiency, and manager’s personal motives. These are discussed next (Healy and Wahlen, 1999; Knoops, 2010).

Bonus plan: The opportunistic perspective of PAT predicts that managers transfer wealth from the firm to themselves. In order to minimize agency costs, the firm arranges a compensation contract that ties managers’ performance to reported income. However, the contract gives managers incentives to select accounting procedures and accruals that increase the firm’s profits and therefore the present value of their rewards.

Capital market: Investors and financial analysts use accounting information to value stock prices. This gives an incentive for managers to manipulate earnings and influence short-term stock price fluctuations. By beating analysts’ expectations and encourage investors to buy company’s stocks, these accounting methods aim for higher stock prices and/or firm value.

Company efficiency: The efficiency perspective of PAT assumes that managers adopt particular accounting methods because that method reflects best the underlying economic performance of the firm. By providing this accurate information, investors and other parties will not need to gather information from other sources. These will lead to cost savings.

Manager personal motives: a manager may use increasing earnings management to show positive reported income for personal motives like reputation, job security and career opportunities.

16

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry

3.5 How to measure earnings management?

To measure earnings management, the literature divides accruals in non-discretionary accruals and discretionary accruals (also known as abnormal accruals). Non-discretionary accruals are accounting adjustments on cash flow that are set by the accounting standards. Discretionary accruals are estimates made within the discretion of the manager. Ronen and Yaari (2008, p. 372) use the following definition: “ Non-discretionary accruals are accruals that arise from transactions made in the current period that are normal for the firm given its performance level and business strategy, industry conventions, macro-economic events, and other economic factors. Discretionary accruals are accruals that arise from transactions made or accounting treatments chosen in order to manage earnings.” In empirical studies discretionary accruals are used as proxy for earnings management, because those are the accruals where management can use their discretion on. McNichols (2000) presents an overview of three kinds of research designs that are commonly used in the literature to measure earnings management:

(i) Research based on aggregate accruals

This method identifies discretionary accruals by using a relation between total accruals and hypothesized explanatory factors. Healy (1985) takes the total accruals (TA) from period t with earnings management applied and assumes that the average total accruals in the previous years are similar to non-discretionary accruals (NDA) with no earnings management applied. Discretionary accruals (DA) are then measured by deducting average total accruals (contains only NDA) in the previous years from the total accruals (contains NDA and DA) in period t. The DeAngelo model

(1986) is like the Healy model, but the estimation period for non-discretionary accruals is restricted to last year’s observation instead the average of previous years. Both the Healy and DeAngelo model don’t take into account that period t, where the total accruals in which earnings management is expected, can be influenced by the economic fluctuations. The fluctuations of supply and demand can have significant influence on accruals (VanderBauwhede 2003).

Jones (1991) introduced a version to control for non-discretionary factors influencing accruals. The

Jones model relaxes the assumption that non-discretionary accruals are constant. It uses a regression approach, specifying a linear relation between total accruals and change in sales and property, plant and equipment. First total accruals need to be calculated, which is defined as the difference between net income before extraordinary items (EXBI) and cash flow from operations (CFO). The basic estimation equation is as follows:

(1) 𝑇𝐴 = 𝐸𝑋𝐵𝐼 − 𝐶𝐹𝑂

Secondly, the estimated TA is used in equation (2) to calculate the coefficients:

17

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry

(2) 𝑇𝐴

𝐸𝑠𝑡𝑖𝑚𝑎𝑡𝑒𝑑

= 𝛼

1

(

1

𝐴𝑆𝑆𝐸𝑇𝑆 𝑡−1

) + 𝛼

2

(Δ𝑅𝐸𝑉 t

) + 𝛼

3

(𝑃𝑃𝐸 𝑡

)

(3) 𝑁𝐷𝐴 𝑡

= 𝛼

1

(

1

𝐴𝑆𝑆𝐸𝑇𝑆 𝑡−1

) + 𝛼

2

(Δ𝑅𝐸𝑉 t

) + 𝛼

3

(𝑃𝑃𝐸 𝑡

)

(4) 𝑇𝐴

𝐸𝑠𝑡𝑖𝑚𝑎𝑡𝑒𝑑

= 𝑁𝐷𝐴

𝐸𝑠𝑡𝑖𝑚𝑎𝑡𝑒𝑑

+ 𝐷𝐴

Where:

NDA t

= estimated non-discretionary accruals and TA is total accruals in year t ;

ASSETS t-1

= lagged total assets

PPE t

ΔREV t

= gross value of property, plant and equipment

= change of revenues scaled by ASSETS.

The estimated total accruals are used to calculate the coefficients α

1

, α

2

, α

3

. When the coefficients α

1

,

α

2

, α3 are determined, they can be put in equation (3): NDA t

= α

1

+ α

2

PPE t

+ α

3

Δ REV t

and have

NDA calculated. Then, discretionary accruals are calculated as the difference between estimated TA and estimated NDA. Most of the improved models are based on the Jones model. The difference lies in how to calculate NDA. A frequently used and improved model is the ‘modified Jones model’

(Dechow, Sloan and Sweeny, 1995). Dechow et al. (1995) argue that discretion can be exercised over sales-based revenues (REV) in the Jones model and cause error in measuring discretionary accruals.

They eliminate this error by assuming that only collected revenues are non-discretionary. The modification is (ΔREV – ΔREC), where REV is revenues and REC is net receivables. Another popular model is the ‘linear performance matching Jones model’ from Kothari et al. (2005). They found former models lacking controls for performance in companies. To control for the effect of performances the variable return on assets (ROA) is added to the modified Jones formula. They suggest that measuring accruals can be more accurate this way.

McNichols (2000) argued that

“…aggregate accrual models that do not consider long-term earnings growth are potentially misspecified and can result in misleading inferences about earnings management behavior.”

She suggests that future progress in earnings management literature is more likely to come from specific accrual and distribution-based tests tan from aggregate accrual tests.

(ii) Distribution-based approach

This research design examines the statistical properties of earnings in order to identify behavior that influences earnings. The focus is on the behavior of earnings around a specified benchmark, such as zero or a prior quarter’s earnings. Earnings that are smoothly distributed around the benchmark are not

18

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry being manipulated and earnings that reflect discontinuities are due the exercise of discretion by management.

(iii) Specific accrual approach

This approach narrows the tests to examine earnings management by using specific accruals in a certain industry. The focus on a certain industry can better distinguish an accrual as significant and to have substantial judgment. The specific industry accruals with accounting discretion are more likely to be used for earnings management. For the banking industry the specific accrual is identified as loan loss provision. Like aggregate accruals studies, it is crucial to identify the discretionary and nondiscretionary components.

The specific accrual approach has several advantages and disadvantages (McNichols, 2000, p. 333).

An advantage is that the researcher can gather information on the specific factors that influence accruals’ behavior. Secondly, by examining the business practices of one industry researchers can pinpoint accruals that need judgment and have material influence on earnings. Another advantage is that a specific industry gives insight on control variables to make a more accurate earnings management proxy. Finally, the specific accrual approach provides a direct link between the relation of the single accrual and explanatory factors. There are also some disadvantages. When it is not clear whether management has discretion over an accrual, it will reduce the power of a specific accrual test.

Further, when researchers want to test the magnitude of manipulation on earnings instead of the association with hypothesized factors, then each specific accrual likely to be manipulated requires its own model. Moreover, it is more costly to examine specific accruals than aggregate accruals, since more institutional knowledge and data is required. And last, the sample of the specific industry might be smaller than the aggregate accrual approach. This may limit the generalizability of the test’s results and may not be able to identify earnings management behavior when specific accruals are not sufficient sensitive.

3.6 Earnings management in the banking industry

In the banking industry there are other motivations to apply earnings management and different types of accruals for detecting earnings management than in the aggregate industry studies. Furthermore, banks and other financial companies are often excluded in previous studies because of the different regulation environment. These aspects are discussed next.

3.6.1 Regulation

An important regulation for banks is based on the requirement of minimal capital ratios, which prevent banks to go bankrupt. When banks are reaching low capital ratios, there will be an increase in

19

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry monitoring from authorities and in severe cases intervening in the operations of banks with inadequate capital will be the consequence and can even end with dismissing management (Beatty et al. 1995, p.

234).

Cheng et al. (2009) examined the effect of minimum capital ratio on earnings management in the banking sector, using 712 bank year observations in the period 1994-2007. They argue that potential regulatory intervention may influence earnings management incentives in two ways. Since regulators intend to monitor weak banks and intervene when capital ratios are close to minimum, it is likely that managers use earnings management to avoid regulatory intervention and even more with high equity incentives. On the other hand, there is a greater chance for earnings management to be detected when regulators do intervene. The discretionary component of loan loss provisions as proxy for earnings management in banks is estimated using the Beaver and Engel (1996) model. Their results indicate that bank managers with high equity incentives are not positively related to earnings management. But when capital ratios are low and the likelihood of regulatory intervention is high, managers with high equity incentives are positively associated with upward earnings management. In addition, managers with high equity incentive have more future sales when capital ratios are close to minimum. However, managers with high equity incentives don’t show strong selling behavior and don’t manage earnings upward when there is no threat of regulatory intervention.

Internationally, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision sets a framework, currently Basel

Accord II, to ensure that a bank holds capital reserves that suit the market or credit risks the bank exposes itself. In other words, the greater the risk to which the bank is exposed, the more capital the bank needs to safeguard its solvency and integrity. To measure their loan’s risk exposure, banks use a risk management tool called the Value-at-Risk (VaR) model. VaR provides in a single number the measurement of summarized risk of possible losses in a financial instruments portfolio (Linsmeier and

Pearson, 2000). Bank management uses VaR to measure credit or default risks for estimating loan losses and setting capital requirements. International standards require banks to compute their VaR forecasts and in the U.S banks must disclose public market risks using VaR or an alternative model.

VaR disclosure has three objectives: (1) it provides a summarized measure of market risk the bank is exposed to, which reduces the information asymmetry between the company and outsiders; (2) to estimate sufficient provisions for capital losses; and (3) to allow the regulator to assess the validity of the VaR model (Pérignon et al. 2008, p. 784). However, each bank may use its own internal VaR model instead of a standardized measurement framework. Specifically, it is not an obligation for banks to disclose the specificities of their internal VaR model. This means that bank management has discretion over these models and can underestimate their VaR estimates to reduce provisions for loan losses and capital requirements. Higher provision for loan losses means a lower profitability. By reducing provisions for loan losses, bank management can increase their reported earnings.

20

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry

The discretion which management possesses for estimating the amount of loan loss provisions need to be within the regulatory guidelines for the loan impairment. The Financial Accounting Standards

Board provides accounting standards for the recognition and measurement of loan losses. Under FAS

No.5 a bad loan is recognized when (1) “it is probable that an asset has been impaired” and (2) “the amount of the loss can be reasonably estimated”. Under FAS No. 114 a loan is impaired when “it is probable that a creditor is unable to collect all interest and principal when contractually due according to the terms of the loan agreement.” A restructured loan is also considered impaired and will be reclassified as nonperforming asset. The bank must value the impaired loan by discounting the expected cash flow, basing the impairment value on the loan’s price in the secondary market or the fair value of the collateral if assets secure the loan (Handorf and Zhu, 2006, p. 100).

3.6.2 Loan loss provisions and motivations

The banking industry has several accruals that are materially significant and requires substantial judgment. Beatty et al.(1995, p. 233) mentioned accruals like loan charge-offs, loan loss provisions, miscellaneous gains and losses, gains from pension settlements and changes in external funds.

However, the accounting literature frequently focuses on loan loss provisions (LLP) for detecting earnings management in banks. Some of these studies are from Beaver and Engel (1996), Ahmed

Takeda and Thomas (1999) and Cheng Warfield and Ye (2009). The LLP is a large accrual for banks, which has significant impact on banks’ earnings and capital stock. Cornett et al. (2009, p. 414) define

LLP as

“…an expense item listed on the income statement reflecting management’s current period assessment of the level of future loan losses.” The main purpose of LLP is to adjust bank’s loan loss reserves to reflect expected future losses on their loan portfolios (Ahmed et al. 1999, p. 2). However, bank managers may have incentives to use LLP for managing earnings.

Beaver and Engel (1996) and other researchers find four motivations for discretionary behavior with respect to LLP: regulatory, financial reporting, tax factors and signaling. In addition, earnings smoothing is also an incentive to manipulate LLP (Cheng et al. 2009; Anandarajan et al. 2007; Ahmed et al. 1999).

Regulatory motivations arise because regulators use capital ratios for measuring the bank capital risks and for identifying banks with low solvency. When the capital ratio nears the minimum capital requirement it is likely for banks to manage earnings. Beatty et al. (1995, p.

233) document that approaching the primary capital ratio of 5.5% is costly for banks, because it increases the chance of regulatory scrutiny.

Financial reporting motivations arise because contracts written by the bank are stated in terms of accounting numbers. Exercising discretion over LLP can affect the economic value of a bank and its managers.

21

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry

Incentives for tax purposes arise because tax expenses represent a significant cost to banks.

Prior research finds that banks can reduce the present value of tax payments by timing transactions (Beatty et al. 1995).

Signaling occurs when a ‘stronger’ bank wants to distinguish itself from ‘weaker’ banks. LLPs are used to signal private information about future intentions of higher earnings to investors and the stock market. Increasing LLP is considered a sign of strength.

Earnings smoothing motives arise due to earnings volatility. A smoother stream of earnings reduces the information asymmetry between managers and stakeholders, therefore reducing the cost of capital. Beatty and Harris (1999, p. 301) claim that public banks engage more in earnings management than private banks due to greater agency cost and greater information asymmetry in public banks. Also, less volatility convey a signal of lower risk, thereby preventing the chance of potential scrutiny from regulators.

3.7 How to measure earnings management in banks

Beaver and Engel (1996) investigated how the capital market values the discretionary and nondiscretionary components of a large accrual in the banking sector, the allowance of loan losses. They found evidence that the non-discretionary part is negatively priced by market participants, because it reflects the impairment of the loan assets due to loan defaults. The discretionary part is positively priced or valuation-neutral. Their model is similar like the “Jones model” in the sense of detecting the discretionary component of the accrual. They suggest that finding the discretionary component of loan loss allowance, first the non-discretionary part must be estimated by using nonperforming assets and net loan charge-offs as explanatory variables. Nonperforming assets contains bad loans and real estate obtained in foreclosure. Loan charge-offs are depreciations of bad loans during an accounting period and has no direct effect on earnings. Net charge-offs is the difference between gross charge-offs less recoveries of previous charge-offs. If losses exceed recoveries, this value is shown as a negative amount.

The allowance for loan losses (ALL) is a linear function of loans outstanding, nonperforming assets and net loan charge offs. The estimation of the components of ALL is based on the non-discretionary component (NALL). NALL is a function of a set of variables including the net charge-offs (CO); loans outstanding (LOAN); nonperforming assets (NPA) and the one-year-ahead change in nonperforming assets (ΔNPA). The formulation is as follows:

(1) 𝑁𝐴𝐿𝐿 𝑖,𝑡

= 𝛼

0

+ 𝛽

1

(𝐶𝑂 𝑖,𝑡

) + 𝛽

2

(𝐿𝑂𝐴𝑁 𝑖,𝑡

) + 𝛽

3

(𝑁𝑃𝐴 𝑖,𝑡

) + 𝛽

4

(Δ𝑁𝑃𝐴 𝑖,𝑡+1

) + 𝑧 𝑖,𝑡

The model assumes there is no discretionary component in equation (1) and z is the measurement error. However, NALL can’t be observed directly and have to be estimated by regressing ALL on the explanatory variables in equation (2):

22

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry

(2) 𝐴𝐿𝐿 𝑖,𝑡

= 𝛼

0

+ 𝛽

1

(𝐶𝑂 𝑖,𝑡

) + 𝛽

2

(𝐿𝑂𝐴𝑁 𝑖,𝑡

) + 𝛽

3

(𝑁𝑃𝐴 𝑖,𝑡

) + 𝛽

4

(Δ𝑁𝑃𝐴 𝑖,𝑡+1

) + 𝜇 𝑖,𝑡

Since total allowance account (ALL) is the sum of the non-discretionary component (NALL) and discretionary component (DALL), to calculate the discretionary part of loan loss allowance (DALL) the basic estimation equation is:

(3) 𝐴𝐿𝐿 𝑖,𝑡

= 𝑁𝐴𝐿𝐿 𝑖,𝑡

+ 𝐷𝐴𝐿𝐿 𝑖,𝑡

(4) 𝜇 𝑖,𝑡

= 𝐷𝐴𝐿𝐿 𝑖,𝑡

+ 𝜀 𝑖,𝑡

The discretionary part of the accrual (DALL) is equivalent to the residual from equation (2) μ it

, where

μ it

= DALL it

+ ε it

. The discretionary component becomes a proxy for manipulation of the allowance account and ε it

is the error term.

Beaver and Engel also tested their model with loan loss provisions (income statement account) instead of loan loss allowance. The difference with the former model is the changes in loans and nonperforming assets. The equation is as follows:

(5) 𝐿𝐿𝑃 𝑡

= 𝛽

0

(

1

𝐺𝐵𝑉 𝑡

) + 𝛽

1

(𝐶𝑂 𝑡

) + 𝛽

2

(Δ𝐿𝑂𝐴𝑁 𝑡

) + 𝛽

3

(Δ𝑁𝑃𝐴 𝑡

) + 𝛽

4

(Δ𝑁𝑃𝐴 𝑡+1

) + 𝑧 𝑡

Where:

LLP t

= Loan loss provisions at firm in year t ;

GBV t

CO t

Δ LOAN t

ΔNPA t

ΔNPA t+1

= Net book value of common equity plus loan loss allowance in year t;

= Net loan charge-offs in year t;

= Current change in total loans (LOAN t

–LOAN

= Current change of nonperforming assets (NPA t-1 t

);

– NPA t-1

);

= One-year-ahead change of nonperforming assets (NPA t+1

– NPA t

);

Z t

= Error term in year t, also the estimated discretionary loan loss provisions;

β

0

, β

1

, β

2

, β

3

, β

4

= Firm specific parameters.

Net charge-offs is included because current charge-offs provides information regarding future net charge-offs, which in turn influence the expectations of the collectability of current loans. The informativeness of current charge-offs may lead to a positive coefficient. Nonperforming loans and the loan portfolio are both a source of default. Therefore, the coefficients of both these variables are expected to be positive. Since loan loss provisions is an expense for a time period, rather like the allowance account at a point of time, equation (5) uses the current changes in loans and nonperformance assets instead. The one-year-ahead change of nonperforming assets is used as measurement for information that management has about the default exposure of loans that is not explained by the other variables.

23

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry

There are also studies that don’t find LLP to be associated with earnings management. Ahmed et al.

(1999, p. 23) showed strong evidence that LLP is used for capital management and that it reflects changes in the expected quality of loan portfolio, but it not used for earnings management. Wetmore and Brick (1994) didn’t find evidence on income smoothing when determining LLP, instead they find past loan risk, loan quality deterioration and foreign risk to be related to LLP.

Nevertheless, recent studies do find evidence consistent with managers smoothing earnings by using

LLP. Kanagaretnam et al. (2004) examined whether and how managers use LLP to smooth income and to signal private information about their bank’s future prospects. They find evidence consistent with the use of LLP to smooth earnings, especially when the pre-managed earnings variability is greater. The evidence on signaling is less consistent. Lui and Ryan (2006, p. 439) documented that profitable banks smoothed their income downward by overstating LLP for homogeneous loans in the

1990s. These income smoothing were then obscured by accelerating charge-offs of those loans.

According to Cornett et al. (2009), LLP is used as a main tool for managing earnings in commercial banks. As a manager increases (decreases) LLP, then net income decreases (increases). In their research for earnings management in public banks they conclude that CEO’s variable pay sensitivity is positively related to earnings management. In other words, when pay performance sensitivity is high, the managers record fewer LLP and more securities gains.

3.8 Summary and conclusion

Earnings contain important information and are used as measurement of performance. Accrual accounting gives managers the flexibility to exercise discretion over accruals. These circumstances may lead to efficient, opportunistic or fraudulent forms of earnings management. Managers use earnings management to influence political costs, costs of capital, agency costs, personal wealth and stock prices. The specific accrual approach is used to detect earnings management for the banking industry, which has its own regulation, accrual process and earnings manipulation incentives. The effect of regulation on earnings management is ambiguous. Managers can use earnings management to avoid regulatory intervention or they refrain from earnings management because of the probability of detection by regulators. Recent studies suggest that LLP is related to earnings management in the banking industry. The discretionary component of LLP can directly be managed by the manager.

Therefore, DLLP can be used as an earnings management proxy and provide evidence that managers manipulate earnings in banks. The Beaver and Engel (1996) model is used to detect earnings management in banks.

In the next chapter prior studies about the relationship between equity incentives and earnings management are discussed.

24

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry

4. PRIOR EMPIRICAL RESEARCH

The previous chapters have described and explain the theory on equity incentives and earnings management. This chapter discusses empirical studies about the relation between equity incentives and earnings management. In paragraph 4.1 studies about the relation between CEO equity incentives and earnings management are explained. However, some earnings management studies examine the chief financial officer (CFO) instead, since the CFO has significant influence on the financial reports. These are discussed in paragraph 4.2. Next to it, regulators predict that SOX has a mitigating influence on earnings management. Therefore, paragraph 4.3 reviews prior studies which examined the relationship between SOX and earnings management. The chapter ends with a summary and conclusion.

4.1 CEO equity incentives and earnings management

4.1.1 Cheng and Warfield (2005)

Cheng and Warfield examined CEOs equity incentives and earnings management in the period 1993-

2000. They tested the relationship of equity incentives and the selling of stock by managers and found a positive relation between equity incentives and manages’ net future sales of their own firm’s stocks.

Furthermore, they investigated the association between equity incentives and earnings management and whether managers sell more shares after actual earnings management. Their results showed that a higher incidence of meeting or beating analysts’ forecasts is associated with high equity incentives, which leads to more sales of shares after actual earnings management. No evidence was found for managers with low equity incentives. Additional analysis points out that high equity incentives is associated with earnings smoothing, because managers are less likely to report large positive earnings surprises. The authors conclude that high equity incentive managers are more likely to engage earnings management.

4.1.2 Bergstresser and Philippon (2006)

Bergstresser and Philippon examined the association between equity incentives and earnings management in the period 1993-2001. They detect discretionary accruals by using the Jones and the modified Jones model. CEO equity incentives are measured by the dollar change in the value of

CEO’s stock and option holdings that comes from a 1% increase of the firm’s stock price and deflated by total CEO compensation (the ‘Incentive Ratio’). In addition, they assessed the relation between high-accrual periods and the CEO’s option exercises and share sales. Their results showed that CEOs with high equity incentive are associated with firms with high earnings management. Also, periods with high discretionary accruals coincide with unusually option exercises and sales of shares by CEOs and other top executives.

25

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry

However, Hribar and Nichols (2007) argued that the results of studies using absolute discretionary accruals don’t hold once controls for volatility of cash flow and sales are added. Accrual-based earnings management studies (i.e. Healy, 1985; DeAngelo, 1986; Jones, 1991; Dechow et al., 1995) can be distinguished into signed prediction (income increasing or income decreasing) and studies with an unsigned prediction (no particular direction). Recent studies like Bergstresser and Philippon (2006) used unsigned measures (absolute discretionary accruals) of earnings management for their research.

These studies have potential bias arising from the use of unsigned measures of earnings management and their inferences change after controlling for the operating volatility.

4.1.3 Cornett, Marcus and Tehranian (2008)

Cornett et al. investigated the effect of equity incentives and earnings management controlled by the influences of governance structure and firm performance. Their sample consists of firms in the S&P

100 index from the period 1994–2003. They use the modified Jones model to detect discretionary accruals. To measure the compensation structure they used the percentage of total CEO annual compensation comprised of new option grants, with the options valued by the Black-Scholes formula.

Their results suggest that earnings management is lower when there is more monitoring from governance mechanisms. These governance mechanisms reduce the use of discretionary accruals. The positive impact of option compensation on reported profitability is purely cosmetic, since the impact of option compensation strongly encourages earnings management. They conclude that governance is more important and equity-based compensation less important for firm performance than suggested by prior studies.

4.1.4 Ahmed, Duellman and Abdel-Meguid (2008)

Ahmed et al. (2008) investigated whether the association between equity incentives and earnings management changes when influenced by governance mechanisms and involvement of auditors. Their sample consists of 4,403 firm-year observations in the period 2000-2006. They use the modified Jones model for measuring accruals and the ‘incentive ratio’ to measure equity incentives. Instead of using the absolute accruals, the signed discretionary accrual was used. The influence of auditors is measured as the extent of economic dependence on the auditors’ clients. Their results showed that equity incentives are not positively related with earnings management and equity-based compensation has an interest alignment function. However, they found income increasing earnings management when both equity incentives and auditors’ dependence on clients are high. Governance mechanisms like the board of directors and institutional shareholders mitigate this effect.

26

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry

4.2 CFO equity incentives and earnings management

As mentioned previously in paragraph 3.4, Graham et al. (2005) presented evidence that the CFO manages financial reports to influence stock price. In their conclusion they suggest additional motives why CFOs worry about short-run stock price: (i) CFO think that short-run stock price volatility influences cost of capital; (ii) they are afraid to lose their job when the stock price falls; (iii) they believe their skill and reputation is based on short-term stock prices; (iv) managers seek attention from equity analysts to cover their stocks; and (v) CFOs want to avoid embarrassing interrogations by analysts when stock price falls. Further, Graham et al. (2005) concluded that “unless there is a fundamental change in the manner in which stock markets perceive small misses from earnings benchmarks, the pressure that CFOs feel to manage earnings, either via real or accounting actions, and influence analyst expectations is unlikely to go away.”

4.2.1 Jiang, Petroni and Wang (2010)

This research investigates whether the CFO equity incentives are associated with earnings management and compares it with the results of the CEOs. The sample consists of 17,542 firm-years in the period 1994-2007. Jiang et al. mentioned that CFOs’ main responsibility is financial reporting; therefore CFO equity incentives should have a greater effect than that of the CEO in earnings management. They documented that CFOs should not be paid by stock options but rather by fixed salary, because CFOs have a responsibility of ‘minding the cookie jar’. Since CFO acts as the CEO’s agent and the CEO has the power to replace the CFO, it might be thought that the CFO would only serve the CEO’s equity incentives. However, Jiang et al. (2010) believe that CFOs wield significant influence. They investigated the association between CFO equity incentives and earnings management relative to CEO incentives. They found that CFO equity incentives are significantly more increasing than CEO equity incentives in the pre-SOX period. For the post-SOX period they find that neither

CFO nor CEO equity incentives are increasing. Also, their results showed that the association between

CFO equity incentives and to meet or beat analysts’ forecast dominates that of the CEOs.

4.3 Earnings management and Sarbanes-Oxley

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) has been enacted in 2002 in the United States after the large accounting scandals and large corporations’ failures like Enron and WorldCom. This legislation sets higher standards on financial information quality and new disclosure procedures for public companies in the United States. Sections 302 and 404 have increased top management responsibility of the internal controls over financial reporting and. Section 404 requires public firms to strengthen their internal control systems and to produce an internal control report showing potential material weaknesses if any. Section 302 requires the CEO and CFO personally to certify the annual or quarterly report that there are no material weaknesses or untrue statements. The signing officers can be

27

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry held responsible for establishing, maintaining and abusing intern controls. A fair presentation of the financial report is no longer limited to GAAP, meaning that GAAP cannot be a safe harbor anymore against charges of earnings management practices (McEnroe, 2007). Because the CFO has to certify along with the CEO the periodic reports, the CFOs have the same responsibilities of financial oversight as the CEO. Moreover, when a firm fails to comply with section 404 and financial reports cannot be certified, then the resulting penalties are severe. This makes adopting pernicious earnings management more costly (Ronen and Yaari, 2009, p. 60). It is therefore expected that after the implementation of SOX that earnings management practices will be reduced.

Graham et al. (2005, p. 66) find in their interview and survey research that most earnings management is achieved via real actions instead of using accounting manipulations. Managers are less willing to adopt accrual manipulation strategies within the accounting standards to manage earnings and use real earnings management instead, even when it is considered less costly. The authors state that this substitution might be caused by the implementation of SOX. Cohen et al. (2008) extend the work of

Graham et al. (2005) by documenting that accrual-based earnings management was increasing until the passage of SOX in 2002. They provide evidence that accrual-based earnings management was particularly high in the period preceding SOX and this increasing trend was concurrent with increases of stock option compensation. In post-SOX they find a decline in accrual-based earnings management, but a significant increase in real earnings management. The authors pointed out that firms still perceive that achieving earnings benchmarks is important, using less accruals and more real earnings management. McEnroe (2007) surveyed CFOs and audit partners as to whether they perceived that

SOX significantly reduced earnings management practices in audited financial statements. His findings suggested that SOX legislation hasn’t significantly reduced earnings management, but has been more effective in reducing clear GAAP violations than earnings management within GAAP.

4.4 Summary and conclusion

Prior studies found evidence that CEOs with high equity incentives are more likely to use earnings management to meet or beat analysts’ forecasts and sell options and shares after successfully applied earnings management. However, the positive association between high equity incentives and earnings management can be mitigated by more governance mechanisms and independent auditors. CFOs main responsibility is financial reporting, it is therefore predicted that equity incentives more likely to induce earnings management than CEOs. Due to the heavy focus on small misses of earnings benchmarks by market participants and analysts, the pressure on CFOs to manage earnings is unlikely to go away. Regulators expect that after the implementation of SOX there will be a reduction in earnings management practices. This has succeeded only partially, because it is found that accrualbased earnings management has decreased but there is an increase in real earnings management.

28

Accounting, Auditing & Control - Equity incentives and earnings management in the banking industry

5. HYPOTHESES

After the literature reviews, I develop my hypotheses using the findings written in this thesis. Cheng et al. (2009) didn’t find that bank managers with high equity incentives are more likely to engage earnings management. But when taking regulation into account, they found a positive association between equity incentives and upward earnings management only when bank’s capital ratios are low and the possibility of regulatory scrutiny is high. However, Cheng et al. (2009) didn’t take into account that SOX have influence on earnings management practices. As previously mentioned, SOX has a significant influence on the use of accrual-based earnings management. Therefore I will perform all tests separately for pre-SOX and post-SOX period for the banking industry. Even though prior studies have found a positive accrual based earnings management practices in the pre-SOX period of nonbanks, the regulation and a different compensation package in the banking industry may have different influence on earnings management. However, the equity-based compensation packages of executives in banks are getting more similar as in nonbanks, inducing earnings management behavior.

First I want to confirm the findings of previous studies that CEO equity incentives are positively related with earnings management for the pre-SOX period. My first hypothesis is therefore as follows:

H

1

: There is a positive association between CEO equity incentive and earnings management in the pre-SOX period of the banking industry.

Since the CFO’s main task is preparing financial statements, the impact of CFO’s equity incentives on financial reporting should dominate the impact of CEO equity incentives. Moreover, the CFO can use accrual-based earnings management more as a key tool in response to equity incentives, unlike the

CEO who has more oversight responsibilities and other options to engage earnings management (Jiang et al. 2010). Like the CEO, I predict that the CFO’s engagement to earnings management is positive in the pre-SOX period. The second hypothesis is formulated as:

H

2