20th Century Post War Theatre

advertisement

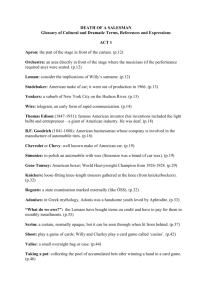

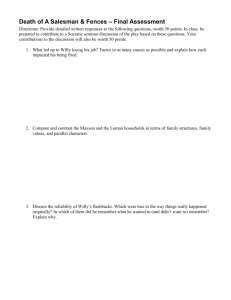

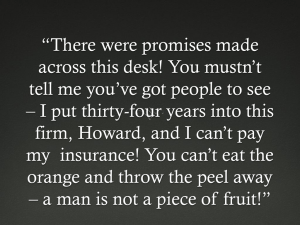

20th Century Post War Theatre 1945-1975 Historical Background World War II left many haunting questions: How could a civilized world engaged in a war that resulted in over 35 million deaths? How could rational societies undertake genocide? Would the atomic bomb result in annihilation of the human race? Is humanity as rational as civilized as philosophers claimed? Could God exist and allow the destruction of so many innocent human beings? Are individuals responsible for group actions? Existentialism Individual human beings are understood as having full responsibility for creating the meanings of their own lives A central proposition of existentialism is that existence precedes essence, that is that a human being's existence precedes and is more fundamental than any meaning which may be ascribed to human life: man defines his reality “Life is meaningless except I choose ___________ meaning.” The fact that we exist is more important that any of the essences that we choose do define it with We can choose to behave ethically or unethically to anyone we meet Theatre of Cruelty Antonin Artaud believed that western theatre needed to be totally transformed Theatre was a sensory experience – viewers senses should be bombarded Theatre is a double, a copy of life and realism is a double of everyday ordinary existence, people in families, going about their daily tasks, but that is not important When we go through life, we are hiding what is really going on What is really going on is much darker, a wild uncontrolled, seething mass of passions, fears, insecurities, loneliness, violence Artaud says: “Without an element of cruelty at the root of every spectacle, the theater is not possible. In our present state of degeneration it is through the skin that metaphysics must be made to re-enter our minds”— Antonin Artaud, Theatre and its Double Theatre should be a double of that life, not real life – it should be cruel, but cruel only to be kind, only to force those feelings out because the fact that everyday life wants to paper over real life and all it does makes it worse Theatre needs to be a purging, take life underneath life to bring it up to the surface If not purged, when this explodes it’s going to be worse than anyone imagined What would lead a person to hack up their neighbor? They exploded, the pressure built up by trying to make everything seem fine when it was not fine Absurdism Martin Esslin – British journalist who was observing Beckett, Ionesco, etc, and noticed similarities in their writings – dubbed them “Theatre of the Absurd” The Purpose of Absurdism is to convince us that some abstraction or another is absurd/meaningless The play then becomes “the objective correlative of their argument” – the play is the point Metaphorical, outside the range of our existence and question things that we always think about Absurdist Characteristics Belief that much of what happens in life cannot be explained logically Attempt to reflect this absurdity in dramatic action Plots do not have traditional climactic or episodic structure Frequently nothing seems to happen because the plot moves in a circle Characters are not realistic and little information about them is given Setting is a strange, unrecognizable location or a topsy-turvy realistic world Language is telegraphic or sparse – dialogue seems to make little sense and the characters fail to communicate: Mr. Smith: Take a circle, caress it, and it will turn vicious. Mrs. Smith: A schoolmaster teaches his pupils to read, but the cat suckles her young when they are small. Mr. Smith: Nevertheless, it was the cow that gave us tails. Samuel Beckett (1906-1989) Dramas deal with the dullness of routine, the futility of human action and the inability of humans to communicate Plays: Waiting for Godot (1953) Endgame (1957) Krapp’s Last Tape (1958) Play (1963) Waiting for Godot (1952) The plot concerns Vladimir (also called Didi) and Estragon (also called Gogo), who arrive at a pre-specified roadside location in order to await the arrival of someone named Godot. Vladimir and Estragon, who appear to be tramps, pass the time in conversation, and sometimes in conflict. Though they make vague allusions to the nature of their circumstances and to their reasons for meeting Godot, the audience never learns who Godot is or why he is important. They are soon interrupted by the arrival of Pozzo, a cruel but lyrically gifted man who claims to own the land they stand on, and his servant Lucky, whom he appears to control by means of a lengthy rope. After Pozzo and Lucky depart, a boy arrives with a message supposedly from Godot, which states that Godot will not come today, "but surely tomorrow." The second act follows a similar pattern to the first, but when Pozzo and Lucky arrive, Pozzo has inexplicably gone blind and Lucky has gone dumb. Again the boy arrives in order to announce that Godot will not appear. The much-quoted ending of the play goes as follows: Vladimir: Well? Shall we go? Estragon: Yes, let's go. They do not move. Interpretation of Godot The intentionally uneventful and repetitive plot of Waiting for Godot can be seen as symbolizing the tedium and meaninglessness of human life The audience never learns who Godot is or the nature of his business with Vladimir and Estragon Waiting for Godot is not a play about nothingness or nothing happening, per se, but rather is about the idea that true meaning exists in the present moment of the act. It suggests a stable moment of truth that is always already real, because it is in a state of existing in the present. Eugene Ionesco (1912-1994) Often turned his characters into caricatures and presented comic characters who lose control of their own existence Concerned with the futility of communication Plays: The Bald Soprano (1949) The Lesson (1951) The Chairs (1952) The Rhinoceros (1959) The Lesson (1951) A male teacher teaches a lesson to a young female student who is good at addition and multiplication but can not subtract, so he kills her. The message is that your teachers are trying to kill you – education is trying to force people’s minds to do things they can’t do and you won’t succeed, and it will kill you Trying to show how people in an education setting are forcing them to change their minds – education is about coercion The Bald Soprano (1949) The Smiths are a traditional family from London, who have invited another family, the Martins, over for a visit. They are joined later by the Smiths' maid, Mary, and the local fire chief, who is also a friend and possibly former lover of Mary's. The two families engage in meaningless banter, telling stories and relating nonsensical poems. As the fire chief turns to leave, he mentions "the bald soprano" in passing, which has a very unsettling effect on the others. Mrs. Smith replies that "she always wears her hair in the same style." The Bald Soprano appears to have been written as a continuous loop. The final scene contains stage instructions to start the performance over from the very beginning, with the Martin family substituted for the Smith family and vice versa. Many suggest that the theme expresses the futility of meaningful communication in modern society. The script is charged with non sequiturs that give the impression that the characters are not even listening to each other in their frantic efforts to make their own voices heard. Harold Pinter (1930- ) Comedy of Menace – frighten and entertain at the same time Feels no need to explain why something happens or who a character is Characters lack explanation of backgrounds or motives Introduction of menacing outside forces Dialogue captures pauses, evasions, and incoherence of modern speech The “Pinter Pause” Pinter is known for use of unbearable silence, with many meticulously considered and immensely significant pauses written into his scripts. What the characters don't say is just as important as the words that do pass their lips. Pinter actually writes silence. When played correctly, Pinter's pauses can be as eloquent as his dialogue. Plays: The Dumb-waiter (1957) The Birthday Party (1957) The Homecoming (1965) The Birthday Party (1957) Taken at face value, the play concerns Stanley, a failed piano player, who lives in a boarding house (run by Meg and Petey), in a British seaside town. On his birthday, Stanley is visited by two men, Goldberg and McCann. A supposedly innocent birthday party quickly becomes a nightmare as Stanley is psychologically tortured, Meg is strangled, and Lulu is sexually assaulted. It is quickly learned that very little of the expository information can be taken at face value. In Act I, Stanley describes his career saying "I've played the piano all over the world. All over the country" and then after a pause simply "I once gave a concert." Much of the plot revolves around the fact that Meg is planning to celebrate Stanley's birthday; a fact that he denies several times throughout the play. (Meg claims he doesn't know that it's his birthday because she's keeping it a secret.) Although Stanley at one point of the birthday party begins to strangle Meg, she has no memory of it the next morning, quite possibly because she had drunk too much the night before. Happenings Non-structured events that occurred with a minimum of planning and organization The idea was that art should not be restricted to museums, galleries or concert halls, but can happen anywhere Street corners, grocery stores, bus stops Selective Realism Type of realism that heightens certain details of action, scenery, and dialogue while omitting others The play is set in a realistic world, but contains unrealistic elements Example: having a narrator or flashbacks Playwrights: Arthur Miller Tennessee Williams Arthur Miller (1915-2005) Focuses on failure, guilt, responsibility for one’s own actions, and the effects of society on the individual Plays: Death of a Salesman (1949) The Crucible (1953) Death of a Salesman (1949) Often classified as a modern “tragedy of the common man” Willy Loman has been a traveling salesman for thirtyfour years. He likes to think of himself as being vital to the New England territory. He asks his wife Linda about his sons, who are home for the first time in years. Willy has trouble understanding why Biff, his thirty-four year old son, cannot find a job and keep it. Biff is attractive and was a star football player in high school with several scholarships; however, he could not finish his education, for he flunked math. When Biff went to Boston to find his father and explain the failure to him, he found Willy in his hotel room having an affair with a strange woman. Afterwards, Biff held a grudge against his father, never trusting him again. Willy explains to his sons that the important things in life are to be well liked and to be attractive. While Biff plans to start his own business with his brother Happy, Willy goes to his boss where he is told that he cannot even represent the firm in New England any more. This news turns Willy's life upside- down. Suddenly unemployed, he feels frightened and worthless. Biff admits that he is tired of living a life filled with illusion and plans to tell his father not to expect anything from him anymore. Biff tries to explain to Willy that he has no real skills and no leadership ability. In order to save his father from disappointment, he suggests that they never see one another again. Willy still refuses to listen to what Biff is saying; he tells Biff how great he is and how successful he can become. Biff is frustrated because Willy refuses to face the truth. In anger, Biff breaks down and sobs, telling Willy just to forget about him. Willy decides to kill himself, for Biff would get twenty thousand dollars of insurance money to start his own business and make it a decent living. At Willy's funeral, no one is present. He dies a pathetic, neglected, and forgotten man. Tennessee Williams (1911-1983) Common theme running through his works is the plight of society’s outcasts Outsiders trapped in a hostile environment Characters are usually victims who are unable to comprehend their world Uses lyrical and poetic language and symbolism to create compassion for characters Plays: The Glass Menagerie (1945) A Streetcar Named Desire (1947) Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1954) A Streetcar Named Desire (1947) Set in the French Quarter of New Orleans during the restless years following World War Two, A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE is the story of Blanche DuBois, a fragile and neurotic woman on a desperate prowl for someplace in the world to call her own. After being exiled from her hometown of Laurel, Mississippi, for seducing a seventeen-year-old boy at the school where she taught English, Blanche explains her unexpected appearance on Stanley and Stella's (Blanche's sister) doorstep as nervous exhaustion. This, she claims, is the result of a series of financial calamities which have recently claimed the family plantation, Belle Reve. Suspicious, Stanley, a sinewy and brutish man, is as territorial as a panther. He tells Blanche he doesn't like to be swindled and demands to see the bill of sale. This encounter defines Stanley and Blanche's relationship. But Stanley and Stella are deeply in love. Blanche's efforts to impose herself between them only enrages the animal inside Stanley. When Mitch -- a card-playing buddy of Stanley's -- arrives on the scene, Blanche begins to see a way out of her predicament. Mitch, himself alone in the world, reveres Blanche as a beautiful and refined woman. Yet, as rumors of Blanche's past in Auriol begin to catch up to her, her circumstances become unbearable. Broadway Broadway has always been traditionally oriented to plays that usually appeal to popular tastes, which is why most of the popular productions since World War II have been MUSICALS Famous Musicals from this era by: Rogers and Hammerstein Oklahoma! (1943) South Pacific (1949) The King and I (1951) The Sound of Music (1959) Annie Get Your Gun (1946) by Irving Berlin Kiss Me Kate (1948) by Cole Porter Guys and Dolls (1950) by Frank Loesser My Fair Lady (1956) by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe West Side Story (1957) by Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim Hello, Dolly (1964) by Jerry Herman Fiddler on the Roof (1964) by Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick A Chorus Line (1975) by Marvin Hamlisch and Edward Kleban Off-Broadway Movement developed in the late 1940s as a reaction to Broadway commercialism Primary goal was to provide an outlet for experimental and innovative works Dedicated to introducing new playwrights and reviving significant plays that had been unsuccessful on Broadway Also popularized intimate playhouses that did not take the traditional proscenium-arch form Usually seated about 200 people