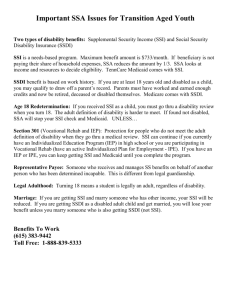

Module 3 – Understanding Social Security Disability Benefits and

advertisement