Generation and Neutralization of Acid in Mining Environments

advertisement

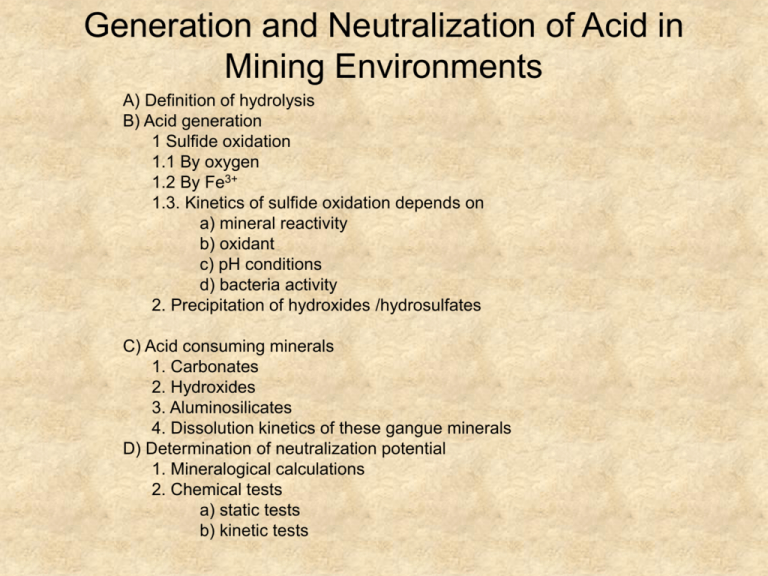

Generation and Neutralization of Acid in Mining Environments A) Definition of hydrolysis B) Acid generation 1 Sulfide oxidation 1.1 By oxygen 1.2 By Fe3+ 1.3. Kinetics of sulfide oxidation depends on a) mineral reactivity b) oxidant c) pH conditions d) bacteria activity 2. Precipitation of hydroxides /hydrosulfates C) Acid consuming minerals 1. Carbonates 2. Hydroxides 3. Aluminosilicates 4. Dissolution kinetics of these gangue minerals D) Determination of neutralization potential 1. Mineralogical calculations 2. Chemical tests a) static tests b) kinetic tests A) Definition of hydrolysis • All geochemical reactions which change pH are hydrolytical reactions • Hydrolysis can be defined as a reaction with water constituents (H+ or OH-) resulting in the formation of solids or stable complexes in solution. Example of complex formation • CaCO3(calcite)+ H2O = Ca2+ + HCO3- + OHExample of mineral precipitation • 2Fe3+ + 3H2O = 2Fe(OH)3 (s) + 6H+ • Note: all equations must balance in terms of elements and charge B) Acid generation The amount of acid generated is a complex function of: (i) the type of sulfide minerals present (ii) their resistance to weathering, (iii) whether the sulfides contain iron, (iv) whether oxidized or reduced metal species are produced by the oxidation, (v) whether elements such as arsenic are major constituents of the sulfides, (vi) whether oxygen or aqueous ferric iron is the oxidant, and (vii) whether hydrous metal oxides or other minerals precipitate as a result of the oxidation process. In the mining environment, there are two important classes of acid producing reactions, oxidation of sulfides and precipitation secondary minerals. 1. Sulfide oxidation 1.1 Reactions with oxygen. • Sulfide minerals that are exposed by erosion or mining are unstable in the presence of atmospheric oxygen or oxygenated ground waters. • Sulfides with metal/sulfur ratios <I, – Iron sulfide (pyrite, FeS 2; marcasite, FeS2; pyrrhotite, Fel-xS), – Arsenopyrite (FeAsS) and sulfosalts such as enargite (Cu3AsS4) • • • generate acid when they react with oxygen and water. FeS2 (pyrite) + 3.5O2 + H2O = Fe2+ + SO42-+ 2H+ Fe0.9S (pyrrhotite) + 1.95O2 + 0.1H2O = 0.9Fe2+ + SO42-+ 0.2H+ FeAsS (arsenopyrite) + 3.25O2 + 1.5H2O = Fe2+ + HAsO42- + SO42-+ 2H+ • Sulfides with metal/sulfur ratios = I, • • • – sphalerite (ZnS), galena (PbS), and chalcopyrite (CuFeS2) do not produce acid when oxygen is the oxidant MeS + 2O2 = Me 2+ + SO42- Me=Zn ,Pb, Cu2+ For example FeCuS2 (chalcopyrite) + 4O2 = Fe2+ + Cu2+ + 2SO42- 1.2 Oxidation by Fe 3+ • Ferric ion forms by Fe2+ +0.5O2 + H+ = Fe3+ + 0.5H2O • Aqueous ferric iron is a very aggressive oxidant • When it reacts with sulfides, it generates significantly greater quantities of acid than oxygen driven oxidation. Pyrite • FeS2 + 14Fe3+ + 8H2O = 15Fe2+ +2SO42-+ 16H+ Chalcopyrite • CuFeS2 + 16Fe3+ + 8H2O = Cu2+ +17Fe2+ + 2SO42- + 16H+ Sphalerite, galena, covellite Me = Zn, Pb, Cu2+ • MeS + 8Fe3+ + 4H2O = Me2+ + 8Fe2+ + SO42- + 8H+ In general, sulfide-rich mineral assemblages with high percentages of iron sulfide or sulfides with iron as a constituent (such as chalcopyrite or iron-rich sphalerite) will generate significantly more acidic water than sphalerite- and galena-rich assemblages without iron sulfide. 1.3 Kinetics of sulfide oxidation: a) mineral reactivity The relative reactivities of sulfides in tailings differ depending on the type of experiment or environment. However, a general sequence from readily attacked to increasingly resistant is: Pyrrhotite(po ) > galena-sphalerite(sph) > pyrite(py)-arsenopyrite(asp) > chalcopyrite(cp) po py Ruttan, Leaf Rapids Corroded sphalerite in oxidized tailings. The rim around the sphalerite grain does not contain Zn. Pyrite is much less altered. sph py cp py Chalcopyrite (cp) disseminated within a quartz grain and armoured against alteration. Py Si Po Aspy Snow Lake Residue Pile INCO Hard pan b) oxidant Sulfide oxidation by ferric iron occurs more rapidly than by oxygen alone. Ferric iron plays a crucial role in determining whether acid will be generated during weathering. c) pH conditions If reaction occurs under acidic conditions (pH<3.5), then a significant quantity of the Fe3+ can remain in solution to react with sulphides. Fe2+ +0.5O2 + H+ = Fe3+ + 0.5H2O When the pH is greater than 3.5, Fe3+ is removed from solution by the precipitation of ferrihydrite or ferric hydroxide 2Fe3+ + 3H2O = 2Fe(OH)3(s) + 6H+ d) bacteria activity Bacteria play catalytic role in ferric ion formation increasing ferrous ion oxidation rate by 105 over abiotic rate. Laboratory microbial oxidation rates and field sulfide oxidation rates are the same, therefore acid generation, is controlled by mineral-microbial interaction. e) Macro and Microstructural Features. Macrostructure. • Ore with a fine grained structure reacts faster than coarse grained ore. • Single sulfide crystals can only be attacked on the surface. • For aggregate grains, oxidants can diffuse along crystal boundaries and may oxidize inside the grain. These sulfides have larger reactive surfaces. • A single crystal grain may many fractures cracks after active mining and milling allowing passage of oxidants. • Natural acid drainage (minimum of pH = 2) is not as acidic as mine drainage (minimum pH =-3 at Iron Mountain CA), because explosions inside mine open pathways for oxygen diffusion. Microstructure • Crystal defects and isomorphic mixtures may affect the rate of sulfide dissolution. • Structural defects (point or linear) reduce atomic binding energy and atoms could be pulled out from crystal structure. The more defects the faster the rate of oxidation. • Isomorphic mixtures can also reduce energy of the crystal lattice, because binding energy of impurity atoms may be lower than that of matrix. 2. Precipitation of hydroxides /hydrosulfates and carbonates • Precipitation of hydrous oxides during the sulfide oxidation process lead to the formation of acid. 2Fe3+ + 3H2O = 2Fe(OH)3(s) + 6H+ • Some non-sulfide minerals such as siderite (FeCO3) and alunite (KAI3(SO4)2(OH)6) can generate acid during weathering if hydrous iron or aluminum oxide precipitates. K+ + 3Al 3+ + SO42- + 6H2O = KAl3(SO4)2(OH)6 (alunite) + 6H+ Fe2+ + HCO3- = FeCO3 (siderite) + H+ • Twice as much acid generates from same quantity of pyrite when iron hydroxide precipitates. FeS2 (pyrite) + 3.5O2 + H2O = Fe2+ + SO42- + 2H+ FeS2 (pyrite) + 3.75O2 + 3.5H2O = SO42-+ 4H+ + Fe(OH)3(s) C) Acid consuming minerals Acid neutralization is the most significant process controlling pollutants being immobilized into a solid phase In most mineral deposits, acid-generating sulfide minerals are either intergrown with or occur in close proximity to a variety of carbonate and aluminosilicate minerals that can react with and consume the acid generated during sulfide oxidation. However, like the sulfides, the ease and rapidity with which these minerals can react with acid varies substantially. 1. Carbonates Alkaline earth carbonates such as calcite (CaCO3), dolomite (Ca, Mg)(CO3)2 and magnesite (MgCO3) react with acid according to: MCO3 (S) + H+ = M 2+ + HCO3This reaction goes as rapidly as acid generates from oxidized sulfides, therefore carbonates are most significant group of acid consuming minerals. Carbonates buffer the pH of solution from 5 to 8 depending on the ratio of Ca: Fe: Mg. A variety of metal carbonates, such as those of zinc (smithsonite), and copper (malachite and azurite) occur in the oxidized zones of sulfide mineral deposits in dry climates. These minerals are also effective acid consumers. Development of pH buffering zones during early, intermediate and late stages of sulphide oxidation 2. Hydroxides, hydrosulfates and oxides • Hydrous iron or manganese oxides form as a result of the dissolution of their respective carbonates (siderite and rhodochrosite). • If the pH decreases during waste-rock weathering hydroxides and hydro sulfates are dissolved consuming protons. • Iron and aluminum hydroxides buffer solutions at pH of 4 - 4.5 pH 2Me(OH)3(s) + 6H+ = 2Me3+ + 3H2O Me=Al3+, Fe3+ • • Jarosite and alunite may control pH at about 3. KFe3(SO4)2(OH)6 (jarosite) + 6H+ = K+ + 3Fe3+ + SO42- + 6H2O • Iron-, manganese-, and aluminum- oxides, such as hematite, magnetite and pyrolusite can theoretically react with acid in an arid climate. • e.g. Fe2O3 (hematite) + 6H+ = 2 Fe3+ + 3 H2O 3. Alumosilicates • Aluminosilicate, calc-silicate, and some metal-silicate minerals are common components of many mineral deposits or their host rocks. • Acid reacts with aluminosilicate minerals dirong weatherting processes. These acid-consuming reactions can release constituents into solution Mg2(SiO4)3 (forsterite) + 4H+ = 2Mg2+ + H4SiO4(aq) • Other constituents can be transformed into more stable minerals. e.g. potassium feldspar forms aqueous potassium and silica, and solid hydrous aluminum oxide, KAlSi3O8 + H+ = K+ + 3H4SiO4(aq) + Al(OH)3(S) • Anorthite forms kaolinite, CaAl2Si3O8 + 2H+ + H2O = Ca2+ + Al2Si2O5(OH)4 (kaolinite) • Silicates could buffer solutions at pH = 7, but there are not naturally observed equilibria for the dissolution of sulfides and silicates, because silicates dissolve very slowly compared with carbonates. 4. Dissolution kinetics of gangue minerals • Carbonates are dissolved as fast as acid generates from oxidized sulfides. • The weathering of silicates is orders of magnitude slower than for carbonates and has been shown in laboratory experiments to follow the trend of Bowen’s reaction series: olivine > augite > hornblende > biotite > K-feldspar > muscovite > quartz, • A comparable series applies to the plagioclase feldspars, with calcic varieties being the most susceptible to destruction CaAl2Si2O8 (anorthite) > NaAlSi3O8 (albite) D) Determination of neutralization potential • • Determination of neutralizing potential (NP) is a technique to forecast the quantity of acid that could be neutralized by the rock-forming minerals present. NP is measured as kg CaCO3 -equivalent/tonne 1. Mineralogical calculations Mineralogical calculations are based on whole-rock analysis of tailings, study of petrography and empirical data on the resistance of minerals, assuming stoichiometry and kinetics of the reaction • If you know whole rock composition and rock forming minerals present, you may calculate mineralogical (normative) composition of the rock • Then you can calculate NP contribution of each acid consuming mineral • e.g. anorthite NP contribution = Mol wt. calcite x 17.1 x 0.40 = 27.2 kg CaCO3 equivalent/tonne Mol wt. anorthite 100 • NP of tailings is the sum of NP contributions from all minerals. • • Advantages: not expensive (< $50) Disadvantages: takes time (weeks), and is based on many assumptions. 2. Chemical tests • This approach is based on chemical experiments, assuming that the sample is a “black box”. No assumptions of stoichiometry or rates of reaction before experiment. a) Static tests • Sample is boiled in HCl acid or H2O2 • Proton concentration (pH) changes before and after experiment are measured. • Under such strong chemical conditions, all reactions taking many years in natural conditions go fast, • Sulfides oxidize and carbonates dissolve completely. • Advantages: Cheap 35-135$, fast (from hours to days) , • Disadvantages: overestimates NP Comparison of NP from static (Sobek) test and calculation b) Kinetic tests • Leaching test are long term tests. Their objectives are: – to confirm, or reduce the uncertainty in, static tests, – identify dominant reactions, acid generation rates and temporal variety in water quality. • Conditions of experiment are more close to natural conditions. • Advantages: Best NP prediction results • Disadvantages: Expensive (<$5200), takes months or sometimes years to complete