anemia

advertisement

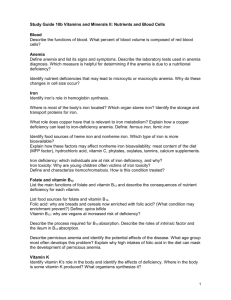

Salman Bin AbdulAziz University College Of Pharmacy anemia is decrease number of RBC or count of hemoglobin or both . What is anemia ? What is classification of anemia ? What is characterizes of each type ? IRON DEFICIENCY ANEMIA 1. D.G., a 35-year-old woman, is seen in the clinic. Her chief complaints include weakness, dizziness, and epigastric pain. She has a 5-year history of peptic ulcer disease, a 10-year history of heavy menstrual bleeding, and a 20-year history of chronic headaches. She has two children who are 1 and 3 years of age .D.G. is currently taking tetracycline (250 mg BID) for acne, ibuprofen (400 mg PRN) headaches, and daily esomeprazole (40 mg). A review of her systems is positive for decreased exercise tolerance. Physical examination reveals a pale, lethargic, white woman appearing older than her stated age. Her vital signs are within normal limits; her heart rate is regular at 100 beats/min. are planned to evaluate her persistent epigastric pain. Her examination is notable for pale nail beds and splenomegaly. Significant laboratory results include the following: Hgb,8 g/dL (normal, 14 to 18); Hct, 27% (normal, 40% to 44%); platelet count, 800,000/mm3(normal, 130,000 to 400,000); reticulocyte count, 0.2% (normal, 0.5% to 1.5%); mean corpuscular volume (MCV), 75 μm3 (normal, 80 to 94); mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), 23 pg (normal, 27 to 31); mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), 30%(normal, 33%to 37%); serumiron, 40μg/dL (normal, 50 to 160); serumferritin, 9 ng/mL(normal, 15 to 200); total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), 450 g/dL (normal, 250 to 400); and 4+ guaiac stools (normal, negative).Iron deficiency is determined to be the cause of D.G.’s anemia. An upperGI serieswith a small bowel followthrough What factors predispose D.G.to iron deficiency anemia? ANSWER Several factors predispose D.G. to iron deficiency anemia.Her history of : I. heavy menstrual bleeding II. chronic use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs III. recurrent peptic ulcer disease, or both. IV. Many women of childbearing age have a borderline iron deficiency that becomes more evident during pregnancy because of the increased iron requirements. V. use of proton pump inhibitors and tetracycline that effect to absorption of iron . 2. What subjective or objective signs, symptoms, and laboratory tests are typical of iron deficiency in D.G.? •constitutional symptoms of weakness and dizziness could be a result of her severe anemia. •increased heart rate, decreased exercise tolerance, and pale appearance are consistent with tissue anoxia •detected by measuring ferritin . inflammatory disorders and liver disease.serum ferritin level <12 ng/mL is consistent with iron deficiency. •Thus, in iron deficiency, the serum ferritin concentration is low, whereas the TIBC is usually high; both of these parameters can be detected before the clinical manifestations of anemia are apparent. •In severe iron deficiency, the RBC become hypochromic (low MCHC) and microcytic (low MCV). Usually, the RBC indices do not become abnormal until the Hgb concentration falls to <12 g/Dl in male patients or <10 g/dL in female patients. 3. How should D.G.’s iron deficiency be managed? What dose of iron should be given to treat D.G.’s iron deficiency anemia and for how long? The primary treatment for D.G. should be directed toward control of the underlying causes of anemia, which in this case are many. D.G.’s iron stores are low because : A. GI blood loss B. multiple childbirths C. heavy menstrual flow D. decreased dietary iron absorption E. Perhaps The usual adult dose of ferrous sulfate is 325mg (one tablet) administered three times daily, between meals . Also don’t take with dairy products 4. What are the differences between iron products? Which is the product of choice? The ferrous form of iron is absorbed three times more readily than the ferric form. Although ferrous sulfate, ferrous gluconate, and ferrous fumarate are absorbed almost equally, each contains a different amount of elemental iron. لالطالع Product formulation is of considerable importance in product selection. Some believe that the more expensive, sustained-release (SR) iron preparations are inherently better. SR preparations fall into three groups: 1. those claimed to increase GI tolerance or decrease side effects, 2. those formulated to increase bioavailability 3. those with adjuvants claimed to enhance absorption. Because these products can be given once daily, increased compliance is an additional claim. Anecdotal claims that SR iron preparations cause fewer GI side effects have not been substantiated by controlled studies. In fact, these products transport iron past the duodenum and proximal jejunum, thereby reducing the absorption of iron. Adjuvants are incorporated into many iron preparations in an attempt to enhance absorption or decrease side effects. Several products contain ascorbic acid (vitamin C), which maintains iron in the ferrous state. Table 86-7 lists a number of combination products that contain a stool softener or vitamin C. Stool softeners are added to iron preparations to decrease the side effect of constipation. 5. What are the goals of iron therapy? How should D.G. be monitored? The goals of iron therapy are to normalize the Hgb and Hct concentrations and to replete iron stores. Initially, if the doses of iron are adequate, the reticulocyte count will begin to increase by the third to fourth day and peak by the seventh to tenth day of therapy. By the end of the second week of iron therapy, the reticulocyte count will fall back to normal. The Hgb response is a convenient index to monitor in outpatients. D.G.’s anemia can be expected to resolve in 1 to 2 months; however, iron therapy should be continued for 3 to 6 months after the hemoglobin is normalized to replete iron stores. During the first month of therapy, as much as 35 mg of elemental iron is absorbed from the daily dose . With time, the percentage of iron absorbed from the dose decreases . 6. What kind of information should be provided to D.G. when dispensing oral iron? What can be done if she experiences intolerable GI symptoms (e.g., nausea, epigastric pain)? Iron should be dispensed in a childproof container, and D.G. should be told to store it in a safe place away from children. Accidental ingestion of even small amounts (three to four tablets) of oral iron can cause serious consequences in small children. She should try to take her iron on an empty stomach because food, especially dairy products, decreases the absorption by 40% to 50% Gastric side effects, which occur in 5% to 20% of patients, include nausea, epigastric pain, constipation, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea. Constipation does not appear to be dose related, but side effects (e.g., nausea and epigastric pain) occur more frequently as the quantity of soluble elemental iron in contact with the stomach and duodenum increases. drug interactions that can occur with iron therapy. Currently, she is taking a proton pump inhibitor, which is thought to inhibit serum iron absorption by increasing the pH of the stomach and decreasing the solubility of ferrous salts. In addition, antacids can increase stomach pH and certain anions (carbonate and hydroxide) also are thought to form insoluble complexes when combined with iron. Although the clinical significance of this is undetermined, D.G. should be advised to take her iron at least 1 hour before or 3 hours after the proton pump inhibitor dose. D.G. also is taking tetracycline for the treatment of acne. Because the absorptions of both iron and tetracycline are decreased when administered concomitantly, the iron should be taken 3 hours before or 2 hours after the tetracycline dose as well. 7. When would parenteral iron therapy be indicated for D.G.? Several indications exist for parenteral iron administration. Malabsorption can be evaluated by measuring iron levels every 30 minutes for 2 hours after the administration of 50 mg of ferrous sulfate. Besides failure to respond to oral therapy as one indication for parenteral iron administration, other indications include intolerance to oral therapy, required antacid therapy, or significant blood loss in patients refusing transfusion. All can warrant injectable iron therapy. In D.G.’s case, if malabsorption is documented, she would be a candidate for injectable iron. 8. What is the preferred route of parenteral iron administration? Iron can be given parenterally in the form of ferric gluconate (Ferrlecit), iron dextran (INFeD and Dexferrum), and iron sucrose (Venofer). Iron dextran, the oldest of the parenteral iron agents Iron dextran can be administered undiluted intramuscularly or by very slow intravenous (IV) injection. IV administration is preferred to intramuscular (IM) administration when muscle mass available for an IM injection is limited; when absorption from the muscle is impaired (e.g., stasis, edema ). Im iron dextran is absorbed in two phases. In the first 72 hours, 60%of the dose is absorbed, whereas the remaining drug is absorbed over weeks to months. IV Infusion iron dextran should not exceed 50 mg (i.e., 1 mL) per minute and daily dose is based on the patient’s weight and should not be >100 mg/day. 9. How is a total dose of iron dextran for IV infusion that would be needed to achieve a normal hemoglobin value for D.G. and to replenish her iron stores calculated? How quickly should she respond? The total dose of iron dextran to be administered can be determined using the following equation: For patients with anemia resulting from blood loss (e.g., hemorrhagic diatheses) or patients receiving chronic dialysis, In this case, the following equation should be used: Iron (mg) = Blood loss (mL) × Het (the patient’s measured Het expressed as a decimal fraction) 10. What side effects can be expected from parenteral iron therapy? Anaphylactoid reactions can occur in <1% of patients treated with parenteral iron therapy. As a result, a 25-mg test dose of iron dextran should be given IM or by IV infusion over 5 to 10 minutes. If headache, chest pain, anxiety, or signs of hypotension are not experienced, the remainder of the dose can be administered parenterally. Pernicious Anemia 11. C.L., a 60-year-old Scandinavian man, is seen by a private physician. C.L. has a 1-year history of weakness and emotional instability.He also complains of a painful tongue, alternating constipation and diarrhea, and a tingling sensation in both feet. Pertinent findings on physical examination include pallor, red tongue, vibratory sense loss in the lower extremities, disorientation, muscle weakness, and ataxia. Significant laboratory findings include the following: Hgb, 9 g/dL (normal, 14 to 18);Hct, 29%(normal, 42%to 52%);MCV 110 μm3 (normal, 76 to 100); MCH, 38 pg (normal, 27 to 33);MCHC, 34% (normal, 33% to 37%); reticulocytes, 0.4% (normal, 0.5% to 1.5%); poikilocytosis and anisocytosis on the blood smear; white blood cell (WBC) count, 4,000/mm3 (normal, 3,200 to 9,800); platelets, 105,000/mm3 (normal, 130,000 to 400,000); serum iron, 80 μg/dL (normal, 50 to 160); TIBC, 300 g/dL (normal, 200 to 1,000); ferritin, 150 ng/mL (normal, 15 to 200); RBC folate, 300 ng/mL (normal, 140 to 460); serum vitamin B12, 100 pg/mL (normal, 200 to 1,000); and anti-intrinsic factor antibody, positive. What signs, symptoms, and laboratory findings are typical of pernicious anemia in C.L.? Pernicious anemia develops from a lack of gastric intrinsic factor production, which causes vitamin B12 malabsorption and , vitamin B12 deficiency. C.L.’s signs and symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency include : 1. painful red tongue 2. loss of lower extremity vibratory sense 3. Vertigo 4. emotional instability. The elevated MCV suggests megaloblastic anemia. Folate and iron are two other factors that can affect the MCV and should be evaluated during the workup of a patient for anemia. In this case, C.L.’s folate and iron levels are normal, but his serum vitamin B12 level is low. The patient’s low serum vitamin B12 levels and the low results obtained from the Schilling test are compatible with the diagnosis of pernicious anemia 12. How should C.L.’s pernicious anemia be treated? How soon can a response be expected? C.L. should receive parenteral vitamin B12 in a dose sufficient to provide not only the daily requirement of approximately 2 mcg, but also the amount needed to replenish tissue stores (about 2,000 to 5,000 mcg; average, 4,000 mcg). To replete vitamin B12 stores, cyanocobalamin can be given IM inaccordance with various regimens. C.L. may receive 100 mcg of cyanocobalamin daily for 1 week, then 100 mcg every other day for 2 weeks, followed by 100 mcg every 3 to 4 days for 2 to 3 weeks. A monthly maintenance dose of cyanocobalamin (100 mcg) would then be required for the remainder of C.L.’s life. Another treatment option may be cyanocobalamin (1,000 mcg) once a week for 4 to 6 weeks followed by 1,000 mcg/mo for lifetime maintenance therapy. IM or deep subcutaneous administration provides sustained release of vitamin B12 with better utilization compared with rapid IV infusion. An oral or intranasal cyanocobalamin gel is also available for maintenance therapy. With adequate vitamin B12 therapy, the following response can be expected: Neurologic symptoms should improve within 24 hours. If maintenance therapy is discontinued, pernicious anemia will recur within 5 years 13. What factors affect the oral absorption of vitamin B12? When is oral vitamin B12 therapy an effective alternative to parenteral therapy? The amount of vitamin B12 that can be absorbed orally from a single dose or meal ranges from 1 to 5 mcg; approximately 5 mcg of vitamin B12 is absorbed daily from the average American diet. The percentage of vitamin B12 absorbed decreases with increasing doses. About 50% of a 1 to 2 mcg dose of vitamin B12 is absorbed, whereas only about 5% of a 20 mcg dose is absorbed. Doses >100 mcg must be ingested to absorb 5 mcg of vitamin B12. Issues of noncompliance or lack of response with oral therapy places the patient at substantial risk for significant neurologic damage. Patients receiving oral vitamin B12 therapy should be monitored more frequently to ensure compliance with therapy Anemias After Gastrectomy 14. F.M. has just undergone a total gastrectomy for recurrent nonhealing ulcers. What form(s) of anemia would be expected to develop in a patient after gastrectomy? Should F.M. receive prophylactic vitamin B12? Partial or total gastrectomy often results in anemia, particularly pernicious anemia, because the source of intrinsic factor is lost, and oral vitamin B12 absorption will be impaired. The hematologic and neurologic abnormalities associated with B12 prophylactic vitamin B12 should be administered to this patient after total gastrectomy. Because the vitamin B12 stores are not currently depleted, maintenance therapy Malabsorption of Vitamin B12 15. P.G., a 55-year-old woman, complained of progressive confusion and lethargy 9 months ago. A CBC at that time revealed only mild leukocytosis. Today, she comes to the emergency department with a 4-week history of frequent (three to five per day) stools containing bright red blood. She reports continued lethargy, dizziness, ataxia, and paresthesias in her hands and feet. Laboratory findings of interest include the following:Hgb, 12.8 g/dL (normal, 12 to 16); MCV, 90 μm3 (normal, 76 to 100); iron, 150 mcg/dL (normal, 50 to 160); B12, 94 pg/mL (normal, 200 to 1,000); folate, 21 ng/mL (normal, 7 to 25); hypersegmented polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN); bilirubin, 3.0mg/dL (normal, 0.1 to 1.0); and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), 520U/L (normal, 50 to 150). A subsequent bone marrow aspirate demonstrates megaloblastic erythropoiesis, giant metamyelocytes, and a low stainable iron. A barium swallow and follow-through show numerous jejunal and duodenal diverticuli. Jejunal and duodenal aspirates reveal aerobic and anaerobic bacterial overgrowth. What signs, symptoms, and laboratory findings are typical for vitamin B12 deficiency in P.G.? The signs and symptoms is : I. Confusion II. Dizziness III. Ataxia IV. Paresthesias V. may be caused by other underlying condition . For example, her lethargy may be the result of prolonged blood loss secondary to diverticulitis. laboratory finding is : I. mild leukocytosis II. Evaluation 9 months later shows a low Hgb III. a low serum vitamin B12 level IV. hypersegmented PMN V. The high LDH and bilirubin levels VI. even though the MCV is within normal limits. P.G.’s history of bloody stools and diverticuli suggests substantial long-termblood loss, which increased demand for iron and vitamin B12 to replace RBC. 16. How should P.G.’s vitamin B12 deficiency be treated? The cause of vitamin B12 malabsorption must be corrected before P.G. is given oral vitamin B12 therapy. medical history, the most likely cause of vitamin B12 malabsorption is bacterial usurpation of luminal vitamin B12. P.G. should first be treated with a broad-spectrum antibiotic (e.g., tetracycline) or a sulfonamide for 7 to 10 days, then begin daily oral vitamin B12 supplementation to replenish her body stores. In this case, normal levels of intrinsic factor permit oral therapy. The recommended daily dose of vitamin B12 is 25 to 250 mcg Folic Acid Deficiency Anemia 17. T.J., a malnourished-appearing woman in her second trimester of pregnancy, presents to the local health clinic for her regular checkup. She is a multiparous, 22year-old woman who ran away from home when she was 16. T.J. has a 7-year history of excessive alcohol intake and has been using cocaine frequently for 3 years. She lives with her boyfriend and her 19-month-old daughter. During both pregnancies, T.J. lost 8 to 10 lb during the first trimester secondary to nausea, vomiting, and anorexia.Her only complaints are dyspnea on exertion, palpitations, and diarrhea. Pertinent laboratory values include the following: Hct, 25.5% (normal, 40%to 44%);MCV, 112μm3 (normal, 76 to 100);MCH, 34 pg (normal, 27 to 33); RBC, 1.1×106 /mm3(normal, 3.5 to 5.0); folate, 30 ng/mL (normal, in RBC 140 to 960); serumvitamin B12,250 pg/mL (normal, 200 to 1,000); reticulocytes, 1%(normal, 0.5 to 1.5); platelets, 75,000/mm3 (normal, 130,000 to 400,000);WBC count, 2,000/mm3 (normal, 3,200 to 9,800) with hypersegmented PMN;LDH, 450U/L(normal, 50 to 150); and bilirubin, 1.5mg/dL (normal, 0.1 to 1). T.J. is not taking any prescriptionmedications. What factors make T.J. at risk for folate deficiency? T.J. has had a history of risk factors for folate deficiency since shewas 16 years of age. T.J. has more than one risk factor for folate deficiency . Cocaine and alcohol, together with multiparity complicated by anorexia, nausea, and vomiting, could lead to poor nutrition. Alcohol has toxic effects on the intestinal mucosa and interferes with folate utilization by the bone marrow . cocaine may be causing anorexia. 18. Which laboratory values support the diagnosis of folate deficiency? How should T.J. be treated and monitored? T.J.’s laboratory values reflect : macrocytic anemia (Hct, 25.5%;MCV, 112μm3) with pancytopenia (reduced number of RBC,WBC, and platelets). Serum vitamin B12 concentrations reflect normal vitamin B12 stores, but folate stores are inadequate as exemplified by the low RBC folate concentration, pancytopenia, and macrocytic anemia. T.J. should be counseled regarding her nutritional and social habits . Because the estimated total body folate store is only about 5 to 10 mcg , 1 mcg of folic acid given daily for 2 to 3 weeks should be more than adequate to replace her storage pool of folate . Higher dosages (up to 5 mcg) may be needed, however, if absorption is compromised by alcohol or other factors. T.J. should continue folate supplements throughout her pregnancy and lactation period. T.J.’s fetus is unlikely to develop folate deficiency because maternal folate is preferentially delivered to the fetus the RBC morphology should begin to revert back to normal within 24 to 48 hours after therapy is initiated and hypersegmented neutrophils should disappear in the periphery in about 1 week. ( )معلومة the anemia should be corrected in 1 to 2 months. Once anemia is corrected, 0.1 mcg of folate as a nutritional supplement should be adequate for maintenance treatment. SICKLE CELL ANEMIA 19. J.T., an 18-year-old man with sickle cell anemia, presented to the emergency department with the chief complaint of rapid onset of abdominal pain and shortness of breath. Since infancy, J.T. has been severely incapacitated by his disease. During early childhood, he experienced several episodes of acute pain, swelling of the hands and feet, and jaundice. Three years before this admission, J.T. required a left hip replacement secondary to bony infarctions. Recently, frequent blood transfusions have reduced the frequency of sickling crises. Physical examination reveals J.T. as a thin black man in acute distress and with scleral icterus. He has a pulse of 110 beats/minute, a respiratory rate of 18 breaths/minute, and a temperature of 98.6◦F. His lungs are clear, and cardiac auscultation reveals a hyperdynamic pericardium and a systolic murmur at the left sternal edge. Splenomegaly is noted, and a chest radiograph reveals only cardiomegaly. A CBC is obtained. Notable results include the following: Hgb, 5.5 g/dL (normal, 14 to 18); Hct, 25% (normal, 42% to 52%);WBC count, 5,000/mm3 (normal, 3,200 to 9,800); platelets, 325,000/mm3(normal, 130,000 to 400,000); reticulocyte count, 1% (normal, 0.5 to 1.5%); bilirubin, 5.8 mg/dL (normal, 0.1 to 1.0); serum creatinine (SrCr), 3.0mg/dL (normal, 0.6 to 1.2); and blood urea nitrogen (BUN), 52 mg/dL (normal, 1 to 18). The peripheral blood smear shows target cells with an occasional sickled cell. What signs and symptoms are consistent with sickle cell anemia? What is J.T.’s current complication? Based on the presence of splenomegaly and anemia with target and sickled cells. The low reticulocyte count is consistent with acute sequestration The hyperdynamic pericardium and systolic murmur are consistent with the high cardiac output required to deliver oxygen in an anemic state 20. How should J.T. be treated? J.T.’s signs and symptoms are sufficiently serious to justify transfusion therapy Splenectomy may be indicated in instances of : I. severe splenomegaly II. repeated infarction or pain in adults III. it is indicated when crises occur in children. Those patients with sickle cell anemia who are bedridden should be placed on chronic heparin therapy to prevent vascular occlusions and deep vein thrombosis ANEMIA OF CHRONIC DISEASE Renal Insufficiency-Related Anemia 21. K.S., a 35-year-old man with a 25-year history of diabetes mellitus, is diagnosed with renal failure and placed on hemodialysis three times weekly.One year later, K.S. is noted to have become increasingly transfusion dependent for correction of his anemia. Significant laboratory values include the following: Hgb, 7 g/dL (normal, 14 to 18); Hct, 26%(normal, 42%to 52%); ferritin, 360 ng/mL (normal, 15 to 200); and serum iron, 98 μg/dL (normal, 50 to 160). In addition, K.S. complains of constant fatigue, poor appetite, and a low energy level. What treatments are available to correct K.S.’s anemia? ANSWER : The cause of the anemia is complex but involves reduced EPO production and a shortened RBC life span. EPO is secreted in the kidney in response to anoxia and is responsible for normal differentiation of RBC from other stem cells, rh EPO is used to treat anemia in patients with renal failure who are undergoing hemodialysis, and K.S. is a candidate for this therapy. Malignancy-Related Anemia 22. T.K. is a 45 year-old woman with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma diagnosed 2 months ago. She is being seen for her third of six cycles of chemotherapy. She complains of shortness of breath and fatigue when she walks up stairs. The only medication T.K. takes is ibuprofen 200 mg PRN for occasional headaches. Her CBC indicates the following: Hgb, 9.7 g/dL (normal, 12 to 16); Hct, 29% (normal, 40% to 44%); MCV, 90 μm3 (normal, 81 to 99); MCHC, 30% (normal, 33% to 37%); serum erythropoietin, 29U/L(normal, 4 to 26).The peripheral smear shows normochromic and normocytic RBC. What is the most likely cause of T.K.’s anemia? What is the appropriate treatment? T.K. appears to have malignancy-related anemia, which is often characterized as anemia of chronic disease or is chemotherapy induced. This anemia is generally normocytic and normochromic and develops when a disease has persisted for >1 to 2 months. Generally, the anemia is mild or moderate, with a limited number of distinguishing characteristics Both the serum iron and TIBC are decreased and transferrin saturation is usually less than normal. Serum ferritin is a reliable measurement of iron stores in patients with chronic disease. Serum ferritin usually is increased, but may be normal; if the anemia is caused by iron deficiency, ferritin values will be decreased. A bone marrow aspirate would reveal an elevated hemosiderin content. Although the prevalence of malignancy-related anemia is difficult to quantify, about 50% to 60% of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, multiple myeloma, or treatment for ovarian and lung cancer develop anemia that requires blood transfusions. Anemia of chronic disease does not respond to treatment with iron, vitamin B12, or folic acid , unless there is an associated vitamin deficiency. Therapy is directed at treatment of the underlying disease, if possible. Large, randomized, multicenter trials have failed to show a clinical benefit to using erythropoietic stimulating agents (ESA) in anemia which is not chemotherapyinduced ESA are not recommended for anemic patients with cancer who are not receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy Alternatively, an RBC transfusion can be given to relieve her symptoms and allow her to better tolerate chemotherapy. In addition, erythropoietic therapy with epoetin alfa or darbepoetin alfa also should be considered. If treatment with epoetin alfa is desired for T.K., therapy can be administered at an initial dose of 150 U/kg subcutaneously three times a week.Alternative dosing regimens, such as 10,000 U three times a week or 40,000 U once a week, have proved to be safe and effective in terms of hematopoietic, quality of life, and transfusion effects. Apositive rhEPO response also can be predicted by observation of an increased serumferritin and decreased transferrin saturation. AIDS-Related Anemia 23. J.M., a 37-year-old man, is currently calling his primary physician with complaints of acute worsening of shortness of breath and pounding in his chest. J.M. has a known history of AIDS and has had recent episodes of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) esophagitis. J.M. also has complained of frequent diarrhea.Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was given intravenously for treatment of PCP; however, J.M. complained of fever while on maintenance therapy. J.M. is currently taking the following medications: dapsone 100 mg/day PO for PCP prophylaxis, ganciclovir 325 mg IV Monday through Friday for CMV prophylaxis, indinavir 800 mg PO Q 8 hours, lamivudine 150 mg PO BID, zidovudine 300 mg PO BID, fluconazole 100 mg/day PO PRN for thrush, and Imodium liquid 5 mL PRN for diarrhea. The only remarkable findings on physical examination include a respiratory rate of 24 breaths/min and a heart rate of 120 beats/minute. A chest examination reveals that J.M. is tachypneic and has bilateral dry rales. The Hickman catheter in the left subclavian vein appears dry and clean. Further workup of J.M.’s illness includes an unremarkable chest radiograph and negative cultures of the blood and sputum.TheCBCincludes normalWBC and platelet counts. Abnormal values include the RBC count of 3,300/mm3 (normal, 4,500 to 6,200),Hgb of 9.1mg/dL,Hct of 28% (normal, 42%to 54%), and a CD4 of 387 cells/mm2 (normal, 440 to 1,600). Themorphology of the RBC wasmoderately anisocytic, normochromic, and normocytic. What factors can contribute to J.M.’s anemia? Anemia occurs in >70% of patients with AIDS and correlates with the severity of the clinical syndrome. In this patient population, anemia is a risk factor for early death. Common symptoms such as : 1. Fatigue 2. Breathlessness 3. difficulties in mental concentration may contribute to this patient population’s decreased quality of life. Approximately 1% of all AIDS-related anemias are related to parvovirus and can be treated and reversed with IV gammaglobulin. Enhanced production of cytokines, such as TNF-α, also may be correlated with hematologic abnormalities. As illustrated by J.M., HIV-associated anemia has a characteristic RBC morphology, which is normochromic and normocytic . Treatment with rhEPO