Chapter 11

advertisement

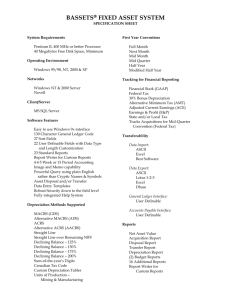

Chapter 11: Depreciation, Impairment and Depletion . 1 Depreciation Depreciation is a method of cost allocation. – it is used to allocate the capitalized cost of PP&E over the years benefited (matching) – Note: depreciation will decrease the carrying value of the asset, but it is not a valuation technique (i.e., book value is not market value) 2 Depreciation The journal entry to record depreciation credits a contra asset rather than crediting the asset directly. This maintains the original cost of the asset, and supplies additional information regarding the approximate remaining life of the asset. Depreciation Expense xx Accumulated Depreciation xx The presentation on the balance sheet shows the cost of the assets net of the accumulated depreciation. This is called book value. 3 Depreciation Methods Depreciation methods (1) Activity (units-of-production) (2) Straight-line (3) Sum-of-the-years’-digits (4) Declining balance (5) MACRS (income tax depreciation) (6) Group and composite methods (7) Hybrid or combination methods 4 Class Example Given the following information regarding an automobile purchased by the company on January 2, 2012: Cost to acquire = $10,000 Estimated life = 4 years Estimated miles = 100,000 miles Salvage value = $2,000 Calculate depreciation expense for the first two years under each of the following methods. 5 (1) Units-of-production (Activity) Assume that the car was driven 20,000 miles in the year 2012, 30,000 miles in 2013,40,000 in 2014 and 20,000 in 2015 Annual depreciation = Cost - Salvage Value x Current Activity Total expected activity Rate = (10,000-2000)/100,000 = $0.08/mi. For 2012= $0.08 x 20,000 = $1,600 For 2013 = $0.08 x 30,000 = $2,400 For 2014 = $0.08 x 40,000 = $3,200 For 2015 = $0.08 x 20,000 = $1,600 XXX So just take bal. to $8,000 = $800 in 2015 (2) Straight-Line Annual depreciation = Cost - Salvage Estimated Life = 10,000 - 2,000 = $2,000 per year 4 years 7 (3) Sum-of-the-years’-digits (SYD) SYD is a systematic allocation that yields an accelerated depreciation in early years and lower depreciation in later years. The basic calculation in SYD involves creating a set of fractions based on the number of years. The numerator starts with the highest year (4 in our example), then declines each year. The denominator is the sum of the years’ total (4+3+2+1 = 10 in our example). Calculations: 2012: 4/10 x (10,000 – 2,000) = 3,200 2013: 3/10 x (10,000 – 2,000) = 2,400 2014: 2/10 x (10,000 – 2,000) = 1,600 2015: 1/10 x (10,000 - 2,000) = 800 Note that SYD does a clean allocation of the total depreciable base of an asset, similar to SL depreciation. 8 (4) Double Declining Balance DDB is an accelerated depreciation technique. It generates more expense in the early years and less in the later years. Annual depreciation = % (Cost - A/D) where A/D is the accumulated depreciation for all prior years, and the percentage is double the straight line rate, or 2 x 1/Estimate life. In the example, the % = 2 x 1/4 = 2/4 = 50%. Depreciation expense (D.E.)for: 2005 = 50% x (10,000 - 0) = $5,000 2006 = 50% x(10,000-5,000) = $2,500 2007 = 50% x (10,000-7,500) = $1,250 XXX So just take bal. to 8,000 A/D = $ 500 2008 (carry fully depreciated) =$0 9 (5) MACRS MACRS (modified accelerated cost recovery system) is a technique developed by the IRS for tax reporting. It utilizes combinations of DDB, 150%DB, and SL to calculate a table of percentages that can be applied to any depreciable asset. Additionally, the IRS assumes no salvage value, and a half year in the first and last year of depreciation (some limitations on fourth quarter purchases). 10 (5) MACRS The IRS supplies a full set of tables with percentages to indicate exactly how much depreciation may be taken each year (see Appendix 11A). Note: companies may use MACRS for tax purposes and another technique, like straightline for financial statement purposes. Many companies keep two separate depreciation schedules - one for financial and one for tax - two different calculations for the same assets. 11 (6) Group and Composite Methods These methods combine assets and depreciate the combined assets at a single average rate. The group method is used for similar assets, where the composite method may include assets of different types. No gain or loss is recognized on asset retirement until the last asset in the group is retired. These methods “smooth out” the estimation error effects, but contain less information for the investors. 12 (7) Hybrid Methods Hybrid methods combine different GAAP methods to achieve a particular result. Some companies combine straight-line with the units of production for depreciation on certain productive assets. Straight-line may be combined with an accelerated technique by switching to straight line when the accelerated technique yields a lower depreciation expense than straight-line. For example, MACRS switches from DDB to straight-line in later years. 13 Depreciation – Partial Years Partial year depreciation may be applied if companies choose to do so. Straight line and DDB have simple calculations in the first, partial year: just depreciate for the portion of the year used. SYD is more complicated, and will not be tested. Companies may also use a “full year” convention for depreciation. If the asset is purchased any time during the year, the company may choose to take a full year’s depreciation that year, or choose to defer any recognition until the next year. 14 Depreciation - Change in Estimate Because depreciation is an estimate, and two of the three components are subject to variability, sometimes we need to make a change in estimate (either in the estimated life or the estimated salvage). The change in estimate affects only the current and future years (prospective); we do not go back and change the previous years that have already been posted. 15 Change in Estimate - continued To calculate the new depreciation expense, first find out how much depreciation has been posted (the Accumulated Depreciation to date). For straight-line, use the following formula (to revise the depreciation rate for current and future years): Remaining Book Value - Revised Salvage Revised Remaining Useful Life 16 Asset Impairment If events occur that might cause a reduction in the value of PP&E below book value, then an asset write-down might be necessary. The first step in the impairment process is a recoverability test. This test estimates the future net (undiscounted) cash flows expected from the asset and its eventual disposition. If the undiscounted future cash flows are equal to or greater than the carrying value of the asset, no impairment is recognized. If the undiscounted future cash flows are less than the carrying value of the asset, then an impairment loss is recognized. 17 Asset Impairment The estimated loss to be recognized is calculated based on the discounted present value of the future cash flows. This is a “two step” process, in which some impairments might not be recognized; however, FASB does not allow a subsequent reversal of the impairment. Note: for assets held for sale, “lower of cost or net realizable value” is used to decide write-down. No depreciation is taken on these assets, and writedown may be reversed if value increases. IFRS has a “one step” process, based on discounted present value, but does allow reversals in subsequent periods. 18 Depletion Depletion is the process of allocating part of the cost of acquiring inventories of natural resources . Natural resources include assets like petroleum, minerals and timber. They are “natural” resources because they may only be replaced by nature. Once the depletion base has been established, most companies use some form of units-ofproduction (activity method) to allocate the cost. The journal entry transfers the current period allocation from the natural resource to Inventory, as the depletion cost is part of the cost of acquiring the inventory. 19 Depletion Costs The depletion base may include – Acquisition costs: the cost to acquire the right to the natural resource (property rights, resource rights, or lease rights). – Exploration costs: the cost to find the resource; these costs may be significant with some resources like oil and gas. 20 Depletion Costs The depletion base may include – Development costs: the intangible costs relating to the extraction of natural resources; these costs may relate to labor, and many of the drilling costs that do not result in a physical asset (tunnels, shafts, wells). Note that tangible costs, such as purchase of reusable rig components, trucks, cranes, etc., are depreciated separately. – Restoration costs: the development of many natural resources leaves land that must be restored (timber and mining, for example). These costs are estimated, recorded as a future liability, and included in the depletion base. 21 Accounting for Oil Exploration Costs Prior to 1977, there were two alternative techniques used to record oil exploration costs: (1) full cost (FC) and (2) successful efforts (SE). FC capitalizes the costs of drilling all the dry holes with the costs of drilling the successful wells, arguing that the dry holes were necessary to find the successful wells (accumulating and matching all costs to future revenues). This technique created a very large asset called “Oil Exploration Costs”. SE capitalizes only the costs relating to the successful wells, and expenses the exploration costs of dry holes in the period incurred. The general split has been that large oil companies use SE, and small companies use FC. 22 Accounting for Oil Exploration Costs In 1977, the FASB required all oil companies to use SE. Small oil companies lobbied Congress, stating that they would be driven out of business, leaving only the large oil companies to control the price of oil. Congress went to the SEC and, in 1978, the SEC proposed an alternative, fair value, technique called Reserve Recognition Accounting (RRA). This technique required estimation of fair value of all of the of the oil companies’ activities, from discovery to production. During the 1978 – 1981 reporting period, companies were permitted to continue with FC and SE, with a disclosure of certain required RRA estimations. 23 Accounting for Oil Exploration Costs In 1981, the SEC dropped the RRA requirements, but maintained the requirement that a fair value estimate of “proven oil reserves” be included. The FASB rescinded its SE requirement, and allowed companies to use either method. The result is that small companies still use FC, and large companies use SE, but all report their “proven reserves.” One benefit from this process is that the FASB now has a more “inclusive” process in its standards development. The Chief Accountant of the SEC now sits on the Emerging Issues Task Force (EITF) and the FASB has never had to rescind another standard because of disagreement with the SEC. 24