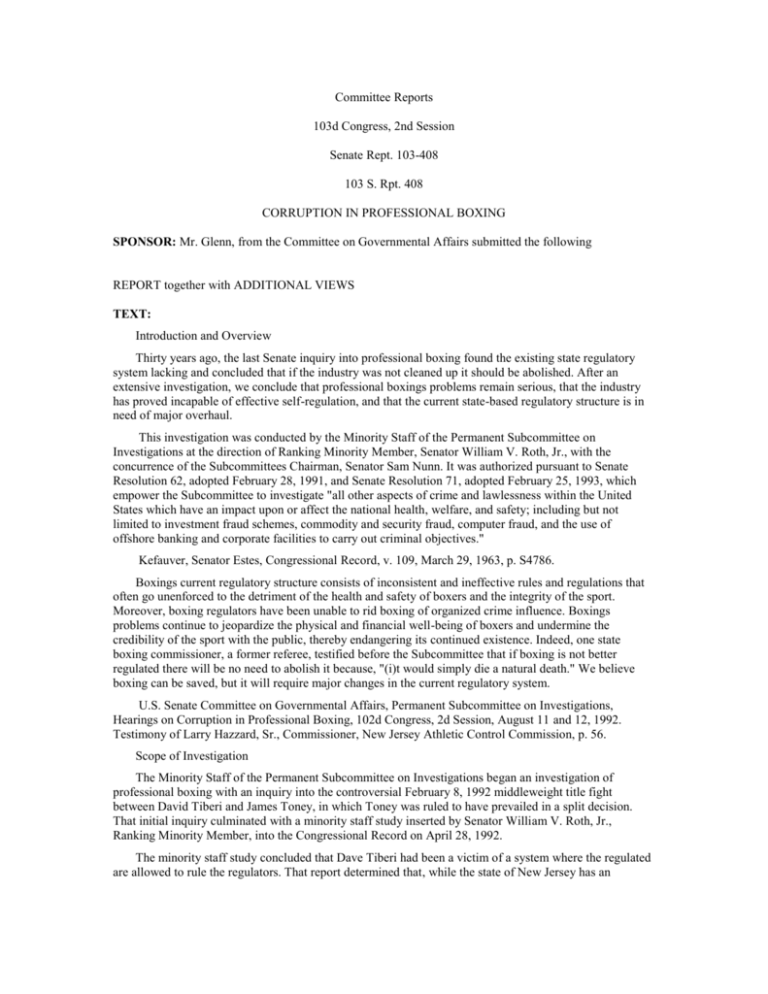

Senate Rept. 103-408 103 S. Rpt. 408 CORRUPTION IN

advertisement