Chapter 5 - Delmar

advertisement

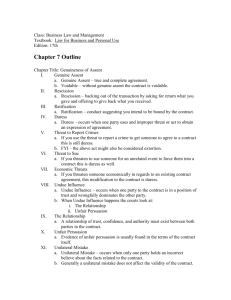

Business Law Chapter 5: Mutual Assent What is Mutual Assent? • Mutual assent is the term that we use to encompass not only the offer and the acceptance, but also the understanding of the parties about what the contract contemplates. Mutual Assent versus Consent • Mutual assent is different from consent. • When a person consents, he or she is agreeing to a particular detail, such as time, place, or action. • Mutual assent, on the other hand, refers to the fact that a party voluntarily assumed the obligations, rights and responsibilities under a contract and all that it entails. Mutual Assent and the Parties’ Preferences • A person can give grudging mutual assent to a contract and be just as bound by its terms as someone who enthusiastically embraces the terms of the contract. Common Design or Purpose • In order to have a valid contract, the parties to the contract must have a common design or purpose. Who Will be Bound? • The parties to the contract must be identifiable. When Mutual Assent is Absent from a Contract • When mutual assent is not present at the time that the contract is negotiated, this deficiency cannot be remedied by later negotiations. • Not every aspect of a contract must be established in order to have a binding contract. Construing the language of a contract • Courts take a very liberal approach to interpreting contracts between parties. • Courts will attempt to enforce a contract and find a contract valid when the parties obviously intended to create one. Interpreting Mutual Assent from a Contract • The courts will review the factual situation presented in each case and make a determination about mutual assent based on what the parties said and did and what the language of the contract itself stated. • The court is presented with an either/or situation when it comes to determining mutual assent. • Either mutual assent was present, or it was not. Interpreting the Language of a Contract – Ground Rules • When a court is called upon to construe the language of a contract, there are some ground rules that will guide the court. Rule #1. Words are given their normal and obvious meaning • Words used by the parties are given their normal and common-sense meaning. Rule #2: The Contract Is Evaluated at the Time of its Creation • The parties’ intentions are assessed at the moment that the contract is created, not by their later misgivings. Rule #3: The Contract is Interpreted to Provide Fairness to All Parties • The general rule is that a contract will not be void for uncertainty unless the court finds it impossible to interpret the intentions of the parties in creating a binding legal agreement between them. Degree of Certainty Required in a Contract • Courts generally rule that obligation of the parties must be reasonably certain and capable of being interpreted. • A contract may be ruled sufficiently definite either because the terms expressed in the contract are specific enough to create a legally binding agreement between the parties or because the contract refers to some other document that clears up any ambiguities. Absolute certainty is not required • Absolute certainty is never a requirement for a contract. • When a court inquires into the specifics of a contract, it focuses on the point in time at which the contract was created. • If the terms of the contract and the subsequent legal obligations of the parties are definite enough at the time when the contract is created, the contract is valid. Mistake as to the subject of the contract • A contract may be voided for mistake, but “mistake” has a very narrow definition under the law. Mistake is a Bilateral Act • A “mistake” refers to an error shared by both sides of the contract. Mistake Concerns Material Facts Only • A material fact is a fact that is crucial to the parties' understanding of the transaction or a key point of negotiation. Mistake and Conditions Precedent • When the parties base their contract on a specific fact and this fact is false, the contract can be voided for mistake. Waiving a Claim of Mistake • A party can waive a claim of mistake by any of the following: 1. By failing to raise the claim within a reasonable period of time. 2. By affirming the contract after learning of the mistake. 3. By a contract provision that clearly states that the party was willing to take on the risk of mistake. How long does a plaintiff have to raise a claim of mistake? • A claim of mistake must be raised within a reasonable period of time. Fraud and Misrepresentation • Fraud: Any kind of trickery used to cheat another of money or property. Two Types of Frauds Involved in Contracts • In most jurisdictions, there are two types of frauds: fraud in the execution of a contract and fraud in the inducement of a contract. Fraud in the Execution of a Contract • Fraud in the execution of a contract, sometimes referred to as “fraud in the factum,” occurs when one party is misled into entering into a contract with another. Fraud in the Inducement • Fraud in the inducement occurs when a party agrees to enter into a contract, understands the rights and responsibilities of the contractual agreement, but has been induced into the agreement by false information provided prior to agreement. Fraud Creates a Voidable Contract • When fraud occurs during the creation of a contract, the contract is not automatically void, at least in the vast majority of jurisdictions. Waiving the Right to Allege Fraud • Some jurisdictions follow a rule stating that if the party could have discovered the fraud through reasonable means, i.e., reading the contract, and failed to do so, then the defense of fraud is no longer available. Proving Fraud • In most jurisdictions, a party alleging fraud must prove the following: a) That the other party made a representation. b) That this representation was about a material fact to the transaction. c) That this representation was false. d) That the party made this false representation with the intent of misleading the plaintiff into relying on the representation. e) That the plaintiff did, in fact, rely on the representation. f) That the plaintiff incurred damages from relying on this false representation. Clear and Convincing Evidence Required to Prove Fraud • Most jurisdictions require that a plaintiff proves an allegation of fraud with clear and convincing evidence. • Clear and convincing evidence: Proof that a particular set of allegations is likely to be true; it is a higher level of proof than preponderance of the evidence. Fraud Involves Material Facts • An allegation of fraud is limited to dishonesty concerning material facts Sales Statements Are Usually Not Considered to be Material Facts • Sales exaggerations or “puffing,” is considered to be harmless since most people do not put much faith in such statements in the first place Opinions Are Usually Not Considered to be Material Facts • A person’s opinion about a particular situation usually does not rise to the level of a material fact. Duress, coercion and undue influence • It is one of the basic principles of contract law that persons cannot have contracts forced upon them. Duress • Duress is the application of unlawful force, or the threat of force, that causes a person to do something that he or she would not otherwise have done. Exercising a Legal Right does not Create a Claim of Duress • It is not duress to exercise a legal option. Coercion • Coercion is a mental threat, compulsion, or force making a person act against free will. Undue Influence • A defense of undue influence often comes about in situations where one person enjoys a position of trust with the plaintiff and then uses that position to deceive the plaintiff into entering a contract. Ratification • A person may approve a previous improper action and make it valid. Ratification and Void Contracts • When a contract is void it cannot be ratified. Actions that Qualify as Ratification • A person ratifies a contract through action. • The only way to successfully ratify a voidable contract is to wait until the legal impediment that made it voidable disappears. Later Agreement • A party can ratify a voidable contract by expressly affirming the contract, even though it is lacking some specific element. Continuing to Receive Benefit • Ratification can also occur through actions. • A court may find that a party has ratified a contract even without a positive statement, where the party continues to receive benefit from the contract, or continues to act as though the contract is perfectly valid. Ratification by Delay • The courts may find that a party ratified a contract simply by its failing to challenge it within a reasonable period of time. The Doctrine of Laches • The principle of laches, sometimes known as the Doctrine of Laches, is simple: when a party has a right and does not assert it, he or she will lose the right. Ratification and Duress • An agreement obtained under duress may also be ratified at some later point in time. • But only when the conditions that created the duress are removed.