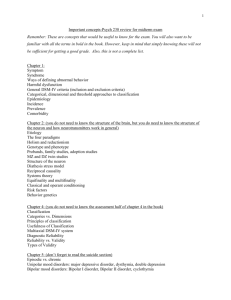

Overview

advertisement

Anxiety Disorders Sarah Melton, PharmD,BCPP,CGP Director of Addiction Outreach Associate Professor of Pharmacy Practice Appalachian College of Pharmacy Oakwood, VA Objectives • Given a case example, evaluate whether the patient meets DSMIV-TR criteria for an anxiety disorder [generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)]. • Interpret common rating scales in the evaluation and management of anxiety disorders. • Distinguish differences in pharmacology, kinetics, efficacy, dosing, adverse effects, and drug interactions of benzodiazepines in the management of anxiety disorders. • Compare the efficacy, dosing, and adverse effects of the serotonergic antidepressants, and the role of antipsychotics in the management of anxiety disorders. Objectives • Evaluate whether patient and professional education is optimal to facilitate safe and effective drug therapy for anxiety disorders. (DII) • Using practice guidelines, develop a pharmacotherapy plan, including dosing and duration of therapy, and nonpharmacologic treatments, for a patient with anxiety disorders. • Discuss the role of pharmacotherapy in the management of anxiety disorders in special populations (e.g., children, elderly patients and pregnancy). • Resolve potential drug-related problems in patients with anxiety disorders. Epidemiology of Anxiety Disorders • As a group - most frequently occurring psychiatric disorders • Over the past decade, prevalence has not changed, but rate of treatment has increased. • Patients are frequent users of emergency medical services, at high risk for suicide attempts, and substance abuse. • Costs for anxiety disorders represent one-third of total expenditures for mental illness. • In primary care, often underdiagnosed or recognized years after onset. • Median age of onset: GAD: 31 years SAD: 13 years OCD: 19 years PTSD: 23 years PD : 24 years • Lifetime prevalence: GAD: 5.7% SAD: 12.1% OCD: 1.6% PTSD: 6.8% PD: 4.7% WFSBP Guidelines for the Pharmacological Treatment of Anxiety, Obsessive Compulsive , and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders- First Revision (2008), Data from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication(2005) Treatment Plan • • • • • • • • Patient preference Severity of illness Comorbidity Concomitant medical illness Complications like substance abuse or suicide risk History of previous treatments Cost issues Availability of treatments in given area Patient Education • Mechanisms underlying psychic and somatic anxiety should be explained. • Describe typical features of the disorder, treatment options, adverse drug effects. • Explain advantages and disadvantages of the drug: – Delayed onset of effect – Activation syndrome or initial jitteriness with SSRIs/SNRIs Duration of Drug Treatment • Anxiety disorders typically have a waxing and waning course. • After treatment response, which often occurs much later in PTSD and OCD, treatment should continue for at least 12 months to reduce the risk of relapse. Dosing • In RCTs, SSRIs and SNRIs have a flat response curve with the exception of OCD – 75% of patients respond to the initial (low) dose – In OCD, the dose must usually be pushed to maximally tolerated dosages • In elderly patients, treatment should be started with half the recommended dose or less to minimize adverse effects • Patients with panic disorder are very sensitive to serotonergic stimulation and often discontinue treatment because of initial jitteriness • Antidepressant doses should be increased to the highest recommended level if the initial low or medium dose fails Dosing • Controlled data on maintenance treatment are scarce – Continue the same dose as in the acute phase • For improved compliance, administer medications in a single dose if supported by halflife data • Benzodiazepine doses should be as low as possible, but as high as necessary • In hepatic impairment, dose should be adjusted Monitoring Treatment Efficacy • Use of symptom rating scales: – – – – – Panic and Agoraphobia Scale (PAS) Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM-A) Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) • Scales are time-consuming and require training • Clinical Global Impression (CGI) or specific selfreport measures may suffice in busy settings Treatment Resistance • Many patients do not fulfill response criteria after initial treatment • Commonly used threshold for response is ≥ 50% improvement in total score of commonly used rating scale • Review diagnosis, assess for adherence, maximally tolerated dosages, sufficient trial period, assess for comorbidities • Change the dose or switch to another medication? • If no response after 4-6 weeks (8-12 weeks in OCD or PTSD), then switch medication • If partial response, reassess in 4-6 weeks • Issue of switching vs. augmentation is debated by experts and not clearly defined in the literature Non-pharmacological Treatment • Psychoeducation is essential – Disease state, etiology, and treatment options • Effect sizes with psychological therapies are as high as the effect sizes with medications • Exposure therapy and response prevention – Agoraphobia, social anxiety, OCD, PTSD • Cognitive Behavioral Therapy – most evidence to support in all disorders – Response is delayed, usually later than medications – Prolonged courses are needed to maintain treatment response – Some evidence to show that treatment gains are maintained over time longer than medications – Expensive, not readily available in rural or remote areas Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) • First-line drugs for all anxiety disorders • Dose and education at initiation of therapy is important – Restlessness, jitteriness, insomnia, headache in the first few days/weeks of treatment may jeopardize compliance – Lower starting doses reduces overstimulation • Adverse effects include headache, fatigue, dizziness, nausea, anorexia • Weight gain and sexual dysfunction are long-term concerns • Discontinuation syndrome: paroxetine • Anxiolytic effect is delayed 2-4 weeks (6-8 weeks in PTSD, OCD) Selective Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) • Efficacy of venlafaxine and duloxetine in certain anxiety disorders has been shown in controlled studies • Early adverse effects such as nausea, restlessness, insomnia and headache may limit compliance • Sexual dysfunction long-term • Modest, sustained increase in blood pressure may be problematic • Significant discontinuation syndrome with venlafaxine occurs, even with a missed dose • Antianxiety effects have latency of 2-4 weeks Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs) • Efficacy in all anxiety disorders is well-proven, except in SAD – Imipramine, clomipramine have most evidence • Adverse effects: initially increased anxiety, anticholinergic, cardiovascular, sedation, impaired cognition, decreased seizure threshold, elevated LFTs (clomipramine) • Weight gain, sexual dysfunction are problematic long-term • Discontinuation syndrome • Avoid in elderly, patients with cardiovascular disease, seizure disorders, and suicidal thoughts • Second-line agents because of adverse effects/toxicity • Dosage should be titrated up slowly; onset of effect is 2-6 weeks, longer in OCD Monamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs) • Efficacy of phenelzine established in panic, SAD and PTSD • Last-line agent for treatment resistance; used by experienced psychiatrists – Risk of adverse effects – Life threatening drug and food interactions • Patient education on dietary restrictions and drug interactions imperative • Give doses in the morning and mid-day to avoid overstimulation and insomnia Benzodiazepines • Anxiolysis begins in 30-60 minutes after oral or parenteral administration • Safe and effective for short-term use; maintenance requires evaluation of risks vs. benefits • Avoid in patients with history of substance or alcohol abuse • Most commonly used in combination with SSRI/SNRI during first few weeks of therapy • Guideline recommendations: Prescribe on scheduled, not prn basis • Not effective in depression Hydrozyzine • Commonly used in community setting; anxiolytic effects that may be beneficial in treating GAD • There are controlled data supporting efficacy, but up to 40% of patients report adverse effects • This agent was similar to buspirone in anxiolytic effects in a short-term trial • Hydroxyzine is not associated with dependence Other Agents PREGABALIN • Not FDA- approved for anxiety, but used commonly in Europe • Effective in acute/long-term GAD and a few trials of SAD • Typical doses of 300-600 mg/day • Onset of activity was evident after 1 week • Adverse effects: dizziness, sedation, dry mouth, psychomotor impairment • Pregabalin was not associated with clinically significant withdrawal symptoms when tapered over 1 week ANTICONVULSANTS • Not used in routine treatment of anxiety disorders, but may some utility as adjunctive agents in some disorders • Carbamazepine, valproate, lamotrigine, and gabapentin have shown efficacy in preliminary studies for PTSD Buspirone – Beneficial only in GAD – Adverse Effects • Nausea, headache, dizziness, jitteriness and dysphoria (initial) – Dosing • Initial 5 mg tid up to maximum 60 mg/day – Advantages • Non-sedating • No abuse potential – Disadvantages • No antidepressant effect for comorbid conditions • Initial therapeutic effect delayed by 1-2 weeks, full effects occurring over several weeks • Ineffective in patients who previously responded to benzodiazepines?? Other Agents ATYPICAL ANTIPSYCOTICS • Quetiapine was effective as monotherapy for GAD • Atypical antipsychotics have been used as adjunctive agents for non-responsive cases of anxiety associate with OCD and PTSD BETA-ADRENERGIC BLOCKERS • β - blockers reduce autonomic anxiety symptoms such as palpitations, tremor, blushing • However, double-blind studies have not shown efficacy in any disorder • Recommended for use in nongeneralized SAD; given before a performance situation Differentiating Anxiety Disorders • Many anxiety disorders present similarly • Key to differentiation is rationale behind fear: – Panic attacks occur in both social anxiety and panic disorder • Fear of anxiety symptoms is characteristic of panic disorder • Fear of embarrassment is from social interactions typifies SAD • GAD is likely diagnosis if anxiety about social situations are part of a pattern of multiple worries • Anxiety may also be induced by medications or medical conditions CASE 1 A 70-year-old man presents to his physician complaining of having trouble sleeping, “being nervous all the time,” and feeling like he is “going to lose control.” His wife died 2 years ago and the symptoms have been getting worse since that time. He is retired as an accountant, but lately cannot even concentrate to pay his own bills. He has seasonal allergies, COPD, angina, and Type II diabetes. Medications include albuterol/ipratropium inhaler, theophylline, enalapril, aspirin, metformin, and loratatadine with pseudoephedrine. He smokes 2 ppd (100 pack years). He drinks 8-10 drinks/day that are caffeinated and also drinks 2-3 beers nightly to help him fall asleep and relieve his “stress.” What factors should be considered in the assessment and differential diagnosis of this patient’s anxiety? Substance-Induced Anxiety • • • • • CNS Stimulants CNS depressant withdrawal Psychotropic medications Cardiovascular medications Heavy metals and toxins Anxiety Secondary to Medical Conditions • Endocrine – Addison’s disease – Cushing disease – Hyperthyroidism – Hypoglycemia – Pheochromocytoma • Cardiovascular – Angina, MI – CHF, MVP • Respiratory – Asthma, COPD – Hyperventilation, PE • Metabolic – Porphyria, Vitamin B12 deficiency • Neurologic – CNS neoplasms, chronic pain – Encephalitis, PD, epilepsy • Gastrointestinal – Crohns Disease, PUD – IBS, Ulcerative Colitis • Inflammatory – RA, SLE • Other – HIV, Malignancy McClure EB, Pine DS. (2009). Clinical Features of the Anxiety Disorders. In BJ Sadock, VA Sadock , P Ruiz (Eds.). Kaplan and Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry (9th ed, pp. 1844-1855). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins. CASE 1 (continued) • Factors that need further investigation before a diagnosis of an anxiety disorder can be made include: – Medical illness (COPD, angina) – Possible depression, adjustment to stressors – Medications/substances • • • • Pseudoepehdrine Theophylline Caffeine Nicotine CASE 2 A 30-year-old woman presents to her PCP c/o of daily headaches, muscle tension, diarrhea and difficulty sleeping. She states that her husband says she is a “worry wart” and she admits that she has difficulty controlling her anxiety over her financial situation, job security, and the safety of her children. She has become irritable because she always “feels on the edge.” The symptoms started 7 months ago, following the death of her sister but she recalls her mother telling her that “she worried too much, just like her father” during her adolescent years. She is employed as an office manager, but has missed several days of work in the past month because of her anxiety, physical symptoms, and inability to concentrate. No significant past medical history and only medications include a multivitamin. PPH: Major Depression 2 years ago treated with fluoxetine 20 mg for 6 months. She is married with 2 children (ages 3 and 6), denies tobacco or alcohol use. Drinks 1 cup of coffee in the morning and an occasional soda in the afternoon. Problem Identification • What symptoms does the patient exhibit that are consistent with Generalized Anxiety Disorder? • What risk factors are present in her history? • What are treatment options? Diagnostic Criteria for GAD • The patient reports having excessive anxiety and worry occurring more days than not for at least 6 months about a number of events of activities (such as work or school performance). • The patient has difficulty in controlling worry. • The anxiety and worry are associated with 3 or more of the following 6 symptoms: – Restlessness or feeling keyed up and on edge – Easily fatigued – Difficulty concentrating, or mind going blank – Irritability – Sleep disturbance (difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep, or restless, unsatisfying sleep) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV-TR, 2000. CASE 2 (continued) • Risk Factors for GAD present in case – Gender (female) – Genetic factors (father) – Medication/substance induced (stimulant) – Stressful event (death of sister) • Treatment options – Nonpharmacologic - Psychoeducation, CBT – Pharmacologic (antidepressants, benzodiazepines, buspirone, others) Pharmacological Treatment of GAD • • • • First-line – Recommended daily doses: • Escitalopram 10-20mg Venlafaxine 75-225 mg • Paroxetine 20-50 mg Duloxetine 60-120 mg • Sertraline 50-150 mg Second-line – Benzodiazepines when patient has no history of dependency; may combine with antidepressants for first 2-4 weeks – Pregabalin 150-600 mg; Imipramine 75-200 mg Others – Hydroxyzine 37.5-75 mg– effective in trials for acute anxiety, but ADRs limit use – Buspirone 15- 60 mg– indicated for GAD, but efficacy results were inconsistent Treatment resistance – Augmentation of SSRI with atypical antipsychotic (quetiapine, risperidone or olanzapine) – Quetiapine effective as monotherapy, but not FDA approved for anxiety because of metabolic and cardiac risks associated with chronic use WFSBP Guidelines for the Pharmacological Treatment of Anxiety, Obsessive Compulsive , and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders- First Revision (2008) CASE 3 A 24-year old college student presents to the student mental health facility for follow-up for treatment of panic disorder with agoraphobia. He presented 5 months ago complaining of attacks of chest pain, SOB, tingling fingers, dizziness, nausea. During the attacks, he felt like he was “outside his body” and “everything was crashing in on him.” He began staying in his apartment nearly all the time and was on the verge of being dismissed from college for not attending classes. He was started on paroxetine 5 mg daily and alprazolam 0.5 mg three times daily. His current doses are paroxetine 40 mg po daily and alprazolam 1 mg in the morning, 1 mg at lunch, and 2 mg at bedtime. He was doing so well that he decided to discontinue the alprazolam yesterday because his mother told him she thought he was “hooked” on it. Today, he feels quite anxious, his heart is racing, and his hands are tremulous. He wonders if he is getting ready to have a full-blown panic attack. What do you recommend at this point in his therapy? Diagnostic Criteria for Panic Disorder • Presence of at least 2 unexpected panic attacks characterized by at least 4 of the following somatic or cognitive symptoms, which develop abruptly and peak within 10 minutes: • Cardiac, sweating, shaking, SOB or choking, nausea, dizziness, depersonalization, fear of loss of control, fear of dying, paresthesias, chills or hot flashes • The attacks are followed by one of the following for 1 month: • Persistent concern about having another attack • Worry about consequences of the attack • Significant change in behavior because of the attack • May occur with or without agoraphobia Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV-TR, 2000. Panic Attack/Agoraphobia • Panic Attack – About 7% of the population will experience at least one panic attack – Types • Unexpected (uncued) • Situationally bound (cued) • Situationally predisposed – Can occur in the context of another anxiety or mental disorder • Agoraphobia – Anxiety about being in a situation where escape is difficult or help is unavailable in the event of a panic attack – Examples of feared situations: open spaces, trains, tunnels, bridges, crowded rooms – Situations are avoided or endured with significant anxiety about having a panic attack or symptoms – Can persist even after panic attacks abate Panic Disorder - Treatment • Non-pharmacologic Treatment – Avoid trigger substances • Caffeine, OTC stimulants, nicotine, drugs of abuse – CBT • Correct avoidance behavior • Train individual to identify and control signals associated with panic attacks • Efficacy – 80-90% short term Pharmacological Treatment of Panic Disorder • First-line – Recommended daily doses • Citalopram 20-60 mg Paroxetine 20-60 mg • Escitalopram 10-20 mg Sertraline 50-150 mg • Fluoxetine 20-40 mg Venlafaxine 75-225 mg • Fluvoxamine 100–300 mg • Second-line – Imipramine 75-250 mg , clomipramine 75-250 mg – Benzodiazepines when no history of dependency; may combine with antidepressants for first 2-4 weeks for more rapid response and to limit ADRs • Alprazolam 1.5-8 mg/day Diazepam 5-20 mg/day • Clonazepam 1-4 mg/day Lorazepam 2-8 mg/day • Treatment-resistance: phenelzine WFSBP Guidelines for the Pharmacological Treatment of Anxiety, Obsessive Compulsive , and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders- First Revision (2008) Panic Disorder: Therapeutic Use of Benzodiazepines • Antipanic effect begins within the first week • Effective in 55-75% of panic disorder patients • Effective in patients needing rapid relief of anticipatory anxiety • Breakthrough (interdose rebound) anxiety may occur 3-5 hours after a dose of shorter acting benzodiazepines such as alprazolam • Dependence/withdrawal are associated with longterm use or high dose Benzodiazepines – Pharmacokinetics • Onset of Action • Metabolic Pathway – High lipophilicity – fastest – Hepatic microsomal oxidation absorption = faster onset but also (Phase I metabolism) “euporic rush” • Impaired by aging, liver • Diazepam, clorazepate, disease, or meds that inhibit alprazolam oxidative process – Lower lipophilicity = longer onset, – Prolonged half-life, less euphoria accumulation • Chlordiazepoxide, – Alprazolam, clonazepam, clonazepam, oxazepam chlordiazepoxide, clorazepate, diazepam • Duration of Action (t1/2) • Long: diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, clonazepam • Short: alprazolam, lorazepam, oxazepam – Glucuronide conjugation (Phase II metabolism) • Lorazepam, oxazepam Benzodiazepines: Drug Interactions • Pharmacodynamic – CNS depressants [alcohol, barbiturates, opiates] • Pharmacokinetic – Inhibitors: cimetidine, nefazodone, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, erythromycin, ketoconazole, oral contraceptives, protease inhibitors, grapefruit juice, isoniazid – Inducers: phenytoin, carbamazepine, phenobarbital, rifampin Benzodiazepines: Dependence and Abuse • Physical dependence • Within 3-4 months, can lead to down-regulation of endogenous GABA production • Withdrawal symptoms common – Rebound anxiety, insomnia, jitteriness, muscle aches, depression, ataxia, blurred vision – Do not stop therapy abruptly – TAPER • Abuse • High risk in patients with substance or alcohol abuse history • Alprazolam, lorazepam, and diazepam Benzodiazepine Withdrawal • Onset, duration and severity varies according to dosage, duration of treatment, and halflife, and speed of discontinuation • Short half-life, withdrawal begins in 1-2 days, shorter duration, more intense • Long half-life, withdrawal begins in 5-10 days, lasts a few weeks • Common symptoms: anxiety, insomnia, irritability, nausea, diaphoresis, systolic hypertension, tachycardia, tremor • Possible consequences: delirium, confusion, psychosis, seizures CASE 3 (Continued) • The patient has had excellent response to pharmacotherapy; however, he has only been treated for 5 months. – Treatment guidelines recommend therapy for at least 1 year after resolutions of symptoms before considering discontinuation • Benzodiazepines are typically used in the first 2-4 weeks as acute therapy, so it is reasonable to consider slowly tapering the alprazolam at this point. • Abrupt discontinuation is not appropriate; he now has withdrawal symptoms that must be addressed, as well as his concern about addiction. Benzodiazepine Discontinuation Typical tapering schedule for benzodiazepines: • 25% per week reduction in dosage until 50% of dose then reduce by one eighth every 4-7 days – Therapy > 8 weeks: taper over 2-3 weeks – Therapy > 6 months: taper over 4-8 weeks – Therapy > 1 year: taper over 2-4 months • For patients on high potency benzodiazepines for monotherapy of panic disorder, a very gradual discontinuation is recommended • Discontinue benzodiazepines slowly over 3-4 months to prevent relapse and emergence of withdrawal symptoms – Alprazolam doses >3 mg/d by 0.5 mg every 2 weeks until 3 mg, then by 0.25 mg every 2 weeks until 1 mg, then by 0.125 mg every 2 weeks – Clonazepam by 0.125 mg every 2 weeks – Diazepam by 2.5 mg every 2 weeks – Lorazepam by 0.5 mg every 2 weeks Diagnostic Criteria for SAD • A marked and persistent fear of one or more social or performance situations involving exposure to unfamiliar people or possible scrutiny by others. The person fears that he or she will act in a way (or show symptoms of anxiety) that will be humiliating or embarrassing • Exposure to the feared social situation provokes anxiety or even a panic attack • The person recognizes that the fear is excessive or unreasonable • Feared social or performance situations are avoided or endured with intense anxiety or distress • The condition interferes significantly with the person's normal routine, occupational (or academic) functioning, or social activities or relationships, or there is marked distress about having the phobia • Specify the disorder as “generalized” if fears include most situations Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV-TR, 2000. Social Anxiety Disorder Treatment • Early detection and treatment is important • Because of the nature of the illness, patients are reluctant to to seek treatment • Pharmacological and nonpharmacological therapy both effective Social Anxiety Disorder Nonpharmacologic Treatment • CBT – Change negative thoughts patterns – Repeated exposure to feared situation – Social skills training – 12-16 weekly sessions, each 60-90 minutes – Workbook with homework exercise – Clinical improvement within 6-12 weeks – Long term gains Pharmacological Treatment of SAD • First-line – Recommended doses: • Escitalopram 10-20 mg Fluoxetine 20-40 mg • Fluvoxamine 100-300 mg Sertraline 50-150 mg • Paroxetine 20-50 mg Venlfaxine 75-225 mg • Second-line – Imipramine 75-200 mg – Clonazepam 1.5-8 mg/day, when patient has no history of dependency; may combine with antidepressants for first 24 weeks • Treatment resistance – Addition of buspirone to an SSRI effective in one open study; buspirone not effective as monotherapy. – Phenelzine WFSBP Guidelines for the Pharmacological Treatment of Anxiety, Obsessive Compulsive , and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders- First Revision (2008) A 28-year old woman presents to the Anxiety Disorders Clinic after being referred by her PCP. The patient recently gave birth to a son 2 months ago. Within 2 weeks after delivery, she started having intrusive thoughts of harming her baby. Over and over again, she imagined herself dropping the baby, cutting or burning him. She checks the appliances in the house multiple times to make sure they are cut off because she fears starting a fire that will harm the baby. She will not use the kitchen knives or scissors. She spends 40 minutes every time she goes out checking and re-checking the baby’s car seat, so now she just stays at home. She reports some relief during the day when she knocks on hard objects in 3 sets of 5 knocks. She is so concerned about hurting her baby that she has started avoiding holding him except when nursing. She says that half of her days are consumed with her checking behavior. Past psychiatric history is positive for depression when she was in college that responded well to sertraline. YBOCS score = 32 Case 4 Diagnostic Criteria for OCD • Obsessions – Recurrent and persistent thoughts, impulses or images that are intrusive and cause a great amount of anxiety – These thoughts, impulses, or images are not worries about daily life issues – Patient attempts to ignore or suppress the thoughts, impulses, images, or to neutralize them by applying special thoughts or actions – The thoughts, impulses, or images are recognized as a product of the patient’s mind • Compulsions – Repetitive behaviors that the person feels “compelled” to perform in response to an obsession, or according to rigid self-imposed rules – The behaviors or mental acts are aimed at preventing or reducing distress or preventing some dreaded event or situation; but are not connected in a realistic or logical way with what they are designed to neutralize or prevent • The person has recognized that the obsessions or compulsions are excessive or unreasonable (this does not apply to children). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV-TR, 2000. OCD Comorbidities • Depression (75%) • Anxiety disorders • Tic Disorders (20-30%) – 5-7% have full Tourette’s syndrome • PANDAS (pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders) • OCD spectrum disorders – Somatoform disorders (body dysmorphic disorder) – Eating disorders (anorexia, bulimia, binge-eating) – Impulse control disorders (trichotillomania, compulsive nail biting, kleptomania, compulsive buying) OCD Non-Pharmacologic Treatment • CBT – Exposure therapy with response prevention – High rate of discontinuation – Effective in 66-75% of patients if continued • Neurosurgery – Intervention to hyperreactive portions of brain – Effective in 40-90% of treatment resistant patients • Deep brain stimulation Pharmacotherapy of OCD • First-line – Recommended doses/day • Escitalopram 10-20 mg Fluoxetine 40-60 mg • Fluvoxamine 100-300 mg Paroxetine 40-60 mg • Sertraline 50-200 mg • Second-line- typically reserved until after failure with 2 SSRIs – Clomipramine 75-250 mg; equally effective as SSRIs but less well-tolerated • Treatment resistance – Intravenous clomipramine (not FDA approved) was more effective than oral clomipramine – SSRI + antipsychotic (haloperiodol, quetiapine, olanzapine, risperidone) more effective than SSRI alone WFSBP Guidelines for the Pharmacological Treatment of Anxiety, Obsessive Compulsive , and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders- First Revision (2008) CASE 4 (continued) • What is the most appropriate therapy for this patient – what do we know? – YBOCS = 32 (extremely severe OCD) – She is breastfeeding – Previous response to sertraline for depression • Treatment algorithm developed by the American Psychiatric Association considers CBT or SSRI to be first-line treatments Case 4 (continued) • The patient declines CBT because of cost and time commitment. • She prefers therapy with medication as she had positive experience when her depression was treated. • Sertraline 25 mg po every AM is prescribed with decision to increase dose to 50 mg by the end of the week. She will follow-up for assessment in one week. Goals of Therapy in OCD • Marked clinical improvement, recovery, and full remission • Decrease symptom frequency and severity, improve the patient’s functioning, and help the patient improve QOL • Enhance the patient’s ability to cooperate with care • Anticipate stressors likely to exacerbate OCD and help the patient develop coping strategies • Minimize any adverse effects • Educate the patient and family about OCD and its treatment. • Reasonable treatment outcome targets include: – less than 1 hour per day spent obsessing and performing compulsive behaviors; no more than mild OCD-related anxiety; an ability to live with uncertainty; and little or no interference of OCD with the tasks of ordinary living Assessment of Response in OCD • Most patients will not experience substantial improvement until 4–6 weeks after starting medication, for some 10–12 weeks. • Higher SSRI doses produce higher response rates and greater magnitude of symptom relief • Doses can be titrated more rapidly in OCD (in weekly increments to maximum dosage), rather than waiting for treatment response for 1-2 months. – Example (Case 4), the patient would go from 50 mg at the end of week 1 to 100 mg at the end of week 2, with subsequent increases of 50 mg/day at weekly intervals up to 200 mg/day. Assessment of Response in OCD • The Y-BOCS rating scale is helpful to document treatment response over time • In clinical trials, OCD “responders” – Y-BOCS scores decrease by at least 25%–35% from baseline – Rated much improved or very much improved on the Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement scale (CGI-I). OCD Duration of Therapy • After response, patient should remain on pharmacotherapy for at least 1-2 years • Medication should be tapered over an extended period of time – Decrease dose by 25% every 2 months • Life-long prophylaxis recommended after 2-4 severe relapses or 3-4 mild relapses Diagnostic Criteria for PTSD Criterion A: stressor The person has been exposed to a traumatic event in which both of the following have been present: • The person has experienced, witnessed, or been confronted with an event or events that involve actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of oneself or others. • The person's response involved intense fear, helplessness, or horror. Note: in children, it may be expressed instead by disorganized or agitated behavior. Criterion B: intrusive recollection Criterion C: avoidance/numbing Criterion D: hyper-arousal Criterion E: duration • Duration of the disturbance (symptoms in B, C, and D) is more than one month. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV-TR, 2000. Subtypes of PTSD • Acute – symptom duration of < 3 months • Chronic – symptom duration of > 3 months • Delayed onset – symptoms begin > 6 months after the traumatic event Acute Treatment After Traumatic Event • Symptoms should diminish over the first few weeks • Social support is critical • 4-5 sessions of time-limited psychotherapy during the first month reduces the rates of PTSD by at least 50% PTSD Treatment Psychotherapy • Education – Nature of the condition – Process of recovery – Understanding that symptoms are a psychobiologic response to overwhelming stress • Goals of Psychotherapy – Reduce the level of distress associated with memories of the event – Reduce the physiological reaction to memories Types of Psychotherapy • Cognitive therapy • Exposure therapy – Imaginal or in vivo exposure • Anxiety management – – – – Relaxation training Stress inoculation training Breathing retraining Assertiveness and positive thinking and self-talk • Interpersonal or group therapy • Play (children) and drama (adults) therapy Pharmacotherapy of PTSD • First-line – Recommended doses/day: • Fluoxetine 20-40 mg Paroxetine 20-40 mg • Sertraline 50-100 mg Venlafaxine 75-300 mg – Prazosin may be more effective in combat-related PTSD • Second-line therapies – TCAs : amitriptyline, imipramine 75-200 mg – Mirtazapine 30-60 mg – Risperidone 0.5-6 mg – Lamotrigine (study doses ranged from 50-500 mg/day) – Nefazodone (effective in small, controlled trial in male combat veterans) • Treatment resistance – Venlafaxine, prazosin, quetiapine + venlafaxine, gabapentin + SSRI WFSBP Guidelines for the Pharmacological Treatment of Anxiety, Obsessive Compulsive , and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders- First Revision (2008) PTSD Treatment: Augmenting Agents Medications PTSD Symptoms Antiadrenergics Hyperarousal, flashbacks and impulsivity – monitor BP, PR Prazosin – nightmares and sleep disruption Startle response, nightmares Psychosis or flashbacks with hallucinations, dissociation Nightmares Irritability, mood swings Anticonvulsants Antipsychotics Cyproheptadine Lithium Acute administration of propranolol superior to placebo in reducing subsequent PTSD symptoms and physiological hyperactivity, but not the emergence of PTSD. Benzodiazepines are not recommended in patients with PTSD; early administration does not prevent emergence of PTSD and may be associated with a less favorable outcome. Foa E. Effective treatments for PTSD, Chapter 6. 2 edition, 2009. The Guilford Press, New York, NY. nd Goals of Pharmacotherapy for PTSD • • • • • Reduce core PTSD symptoms Reduce disability Improve QOL Improve resilience to stress Reduce co-morbidity Treatment of Anxiety Disorders Under Special Conditions • Pregnancy – Risks of drug treatment must be weighed against risk of withholding treatment – Majority of studies indicate that use of most SSRIs and TCAs imposed no increased risk for malformations • Avoid paroxetine due to risk of cardiac malformations – Benzodiazepines are typically avoided in pregnancy because of reports of congenital malformations; however, there is no consistent evidence that benzodiazepines are hazardous • Literature suggests safety with diazepam and chlordiazepoxide; alprazolam should be avoided • Breast feeding: paroxetine, sertraline, nortriptyline are safer; avoid benzodiazepines and fluoxetine Treatment of Anxiety Disorders Under Special Conditions • Children and Adolescents – Many experts feel drug therapy should be reserved for patients who do not respond to psychological therapy – SSRIs are first-line drug treatment – Careful monitoring required for activation syndrome and increased suicidal thoughts or behaviors • Elderly – Increased sensitivity for anticholinergic properties – Increased risk of EPS, orthostasis, EKG changes – Increased risk of paradoxical reactions to benzodiazepines – Few trials evaluate anxiety in the elderly • Venlafaxine efficacious in elderly with GAD • Citalopram effective in patients older than 60 with anxiety disorders Anxiety Disorders CONCLUSION