Evidence-Based Evaluation of Patients with Low Back Pain

advertisement

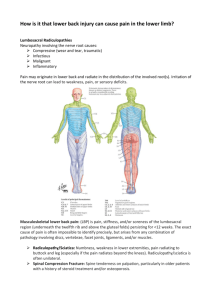

Welcome to Low Back Pain: Evaluation, Management, and Prognosis Welcome and Overview Bill McCarberg Founder Chronic Pain Management Program Kaiser Permanente San Diego, California Adjunct Assistant Clinical Professor University of California School of Medicine San Diego, California Evidence-Based Evaluation of Patients With Low Back Pain Learning Objective Discuss the differential diagnosis for low back pain (LBP) and the importance of clinical red and yellow flags in evaluation of LBP Low Back Pain Guidelines In 2007, the American College of Physicians (ACP) and American Pain Society (APS) issued comprehensive joint clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of LBP Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491. Guideline #1 Clinicians should conduct a focused history and physical examination to help place patients with LBP into 1 of 3 broad categories Nonspecific LBP Back pain potentially associated with radiculopathy or spinal stenosis Back pain potentially associated with another specific spinal cause The history should include assessment of psychosocial risk factors, which predict risk for chronic disabling back pain Strong recommendation Moderate-quality evidence Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491. Focused History and Physical Examination Determine presence and level of neurological involvement1,2 Classify patients into 3 broad categories Nonspecific LBP potentially associated with radiculopathy Spinal stenosis Back pain potentially associated with another specific spinal cause Patients with serious or progressive neurologic deficits or underlying conditions requiring prompt evaluation Tumor Infection Cauda equina syndrome Patients with other conditions that may respond to specific treatments Ankylosing spondylitis Vertebral compression fracture 1. Deyo RA, et al. JAMA. 1992;268(6):760-765. 2. Bigos SJ, et al. Acute Low Back Problems in Adults. Clinical Practice Guideline, No. 14; 1994. Evaluation of Back Pain Site Duration Length of illness Time of onset Spread Mode of onset Quality Precipitating factors Intensity Aggravating factors Frequency Relieving factors Associated features McGuirk BE, et al. In: Ballantyne J, Fishman S and Bonica JJ, eds. Bonica's Management of Pain. 2010:1094-1105. Epidemiology of Low Back Pain 90% of American adults experience an episode of back pain during their lifetime Of patients who have acute back pain 90% to 95% have a non–life-threatening condition Although up to 85% cannot be given an exact diagnosis, nearly all recover within 4 to 6 weeks For 5% to 10% of patients, acute back pain is a manifestation of more serious pathology Vascular catastrophes, malignancy, spinal cord compressive syndromes, and infectious disease processes Winters ME, et al. Med Clin North Am. 2006;90(3):505-523. What Is Seen in Primary Care Practice? In minority of patients presenting for initial evaluation in primary care setting, LBP is caused by1 Cancer (approximately 0.7% of cases) Compression fracture (4%) Spinal infection (0.01%) Estimates for prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis in primary care patients range from 0.3%1 to 5%2 Spinal stenosis and symptomatic herniated disc are present in about 3% and 4% of patients, respectively Cauda equina syndrome most commonly associated with massive midline disc herniation, but rare Estimated prevalence of 0.04%3 1. Jarvik JG, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(7):586-597. 2. Underwood MR, et al. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34(11):1074-1077. 3. Deyo RA, et al. JAMA. 1992;268(6):760-765. Cost of Low Back Pain LBP is one of top 10 reasons patients seek care from family physicians1 Prevalence of LBP has varied from 7.6% to 37% Peak prevalence between 45 and 60 years of age2 Also reported by adolescents and by adults of all ages 80% of adults seek care at some time for acute LBP3 One-third of US disability costs are due to low back disorders3 Direct costs of diagnosing and treating LBP in United States estimated in 1991 to be $25* billion annually4 Indirect costs, including lost earnings, are even higher4 Proper diagnosis and appropriate treatment of LBP saves healthcare resources, relieves suffering *40 billon in 2008 using Consumer Price Index to compute the relative value of money. 1. AAFP. Facts About Family Practice; 1996. 2. Borenstein DG. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1997;9(2):144-150. 3. Kuritzky L, et al. Prim Care Rep 1995;1:29-38. 4. Frymoyer JW, et al. Orthop Clin North Am. 1991;22(2):263-271. Etiology of Low Back Pain Nonspecific LBP Back pain potentially associated with radiculopathy or spinal stenosis Back pain potentially associated with another specific spinal cause Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491. Structural Sources of Low Back Pain Muscles of the back1,2 Interspinous ligaments2-4 Zygapophyseal Sacroiliac joints5-7 joint(s)8 Intervertebral discs9-12 Mechanical12 or chemical irritation of dura mater13 1. Kellgren JH. Clin Sci. 1938;3:175-190. 2. Bogduk N. Med J Aust. 1980;2(10):537-541. 3. Kellgren JH. Clin Sci. 1939;4:35-46. 4. Feinstein B, et al. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1954;36-A(5):981-997. 5. Mooney V, et al. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976(115):149-156. 6. McCall IW, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1979;4(5):441-446. 7. Fukui S, et al. Clin J Pain. 1997;13(4):303-307. 8. Fortin JD, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19(13):1475-1482. 9. Wilberg G. Acta Orthop Scand. 1947;19:211-221. 10. Falconer MA, et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1948;11(1):13-26. 11. Kuslich SD, et al. Orthop Clin North Am. 1991;22(2):181-187. 12. O'Neill CW, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27(24):2776-2781. 13. El-Mahdi MA, et al. Neurochirurgia (Stuttg). 1981;24(4):137-141. Causes of Low Back Pain Possible sources of back pain have been demonstrated; causes have been more elusive Refuted: conditions traditionally considered to be possible causes are actually not causes Eg, spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, degenerative changes (spondylosis) Accepted: tumors and infections Untested: muscle sprain, ligament sprain, segmental dysfunction, and trigger points Known source, unknown cause: sacroiliac joints, zygapophyseal joints, internal disc disruption McGuirk BE, et al. In: Ballantyne J, Fishman S and Bonica JJ, eds. Bonica's Management of Pain. 2010:1105-1122. Diagnostic Triage Guides Subsequent Decision-Making Inquire about Location of pain Frequency of symptoms Duration of pain History of previous symptoms, treatment, and response to treatment Consider possibility of LBP due to problems outside the back Pancreatitis Nephrolithiasis Aortic aneurysm Systemic illnesses (eg, endocarditis or viral syndromes) Differential Diagnosis for Acute Low Back Pain Disease or Condition Patient Age (Years) Back strain 20-40 Acute disc herniation 30-50 Osteoarthritis or spinal stenosis Spondylolisthesis 30-50 Location of Pain Quality of Pain Aggravating or Relieving Factors Signs Low back, buttock, posterior thigh Ache, spasm Increased with activity or bending Local tenderness, limited spinal motion Low back to lower leg Sharp, shooting, or burning pain; paresthesia in leg Decreased with standing; increased with bending or sitting Positive straight leg raise test, weakness, asymmetric reflexes Increased with walking, Low back to Ache, shooting especially up an lower leg; pain, “pins and incline; decreased with often bilateral needles” sensation sitting Back, Any age posterior thigh Mild decrease in extension of spine; may have weakness or asymmetric reflexes Ache Increased with activity or bending Exaggeration of the lumbar curve, palpable “step off” (defect between spinous processes), tight hamstrings Ache Morning stiffness Decreased back motion, tenderness over sacroiliac joints 15-40 Sacroiliac joints, lumbar spine Infection Any age Lumbar spine, sacrum Sharp pain, ache Varies Fever, percussive tenderness; may have neurologic abnormalities or decreased motion Malignancy >50 Affected bone(s) Dull ache, throbbing pain; slowly progressive Increased with recumbency or cough May have localized tenderness, neurologic signs, or fever Ankylosing spondylitis Adapted from: Patel AT, et al. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(6):1779-1786. Guideline #2 Clinicians should not routinely obtain imaging or other diagnostic tests in patients with nonspecific LBP Strong recommendation Moderate-quality Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491. evidence Plain X-Rays for Low Back Pain There is no evidence that routine plain radiography in patients with nonspecific LBP is associated with a greater improvement in patient outcomes than selective imaging1-3 Exposure to unnecessary ionizing radiation should be avoided, particularly in young women (amount of gonadal radiation from obtaining a single plain radiograph [2 views] of the lumbar spine is equivalent to daily chest radiograph for more than 1 year)4 Routine advanced imaging (computed tomography [CT] or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) is not associated with improved patient outcomes,5 identifies radiographic abnormalities poorly correlated with symptoms,6 and could lead to additional, possibly unnecessary interventions7,8 1. Deyo RA, et al. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147(1):141-145. 2. Kendrick D, et al. BMJ. 2001;322(7283):400-405. 3. Kerry S, et al. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(479):469-474. 4. Jarvik JG. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2003;13(2):293-305. 5. Gilbert FJ, et al. Radiology. 2004;231(2):343-351. 6. Jarvik JG, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(7):586-597. 7. Jarvik JG, et al. JAMA. 2003;289(21):2810-2818. 8. Lurie JD, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28(6):616-620. Plain X-Rays for Low Back Pain (cont.) Plain radiography is recommended for initial evaluation of possible vertebral compression fracture in select high-risk patients, such as those with a history of osteoporosis or steroid use1 Evidence to guide optimal imaging strategies is not available for LBP that persists for more than 1 to 2 months if there are no symptoms suggesting radiculopathy or spinal stenosis, although plain radiography may be a reasonable initial option (see recommendation 4 for imaging recommendations in patients with symptoms suggesting radiculopathy or spinal stenosis)2 Thermography and electrophysiologic testing are not recommended for evaluation of nonspecific LBP 1. Jarvik JG, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(7):586-597. 2. Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491. Guideline #3 Clinicians should perform diagnostic imaging and testing for patients with LBP when severe or progressive neurologic deficits are present or when serious underlying conditions are suspected on the basis of history and physical examination Strong recommendation Moderate-quality Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491. evidence CT or MRI Diagnostic Imaging Prompt work-up with MRI or CT is recommended if severe or progressive neurologic deficits or suspected serious underlying condition; delayed diagnosis and treatment associated with poorer outcomes1-3 MRI is generally preferred over CT if available; does not use ionizing radiation, provides better visualization of soft tissue, vertebral marrow, and the spinal canal4 1. Loblaw DA, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(9):2028-2037. 2. Todd NV. Br J Neurosurg. 2005;19(4):301-306. 3. Tsiodras S, et al. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;444:38-50. 4. Jarvik JG, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(7):586-597. CT or MRI Diagnostic Imaging (cont.) There is insufficient evidence to guide diagnostic strategies in patients who have risk factors for cancer but no signs of spinal cord compression Proposed strategies generally recommend plain radiography or measurement of erythrocyte sedimentation rate3, with MRI reserved for patients with abnormalities on initial testing1,2 Alternative strategy is to directly perform MRI in patients with a history of cancer, the strongest predictor of vertebral cancer;2 for patients older than 50 without other risk factors for cancer, delaying imaging while offering standard treatments and reevaluating within 1 month may also be a reasonable option4 1. Jarvik JG, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(7):586-597. 2. Joines JD, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(1):14-23. 3. van den Hoogen HM, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(3):318-327. 4. Suarez-Almazor ME, et al. JAMA. 1997;277(22):1782-1786. Guideline #4 Clinicians should evaluate patients with persistent LBP and signs or symptoms or radiculopathy or spinal stenosis with MRI (preferred) or CT only if they are potential candidates for surgery or epidural steroid injection (for suspected radiculopathy) Strong recommendation Moderate-quality Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491. evidence Imaging for Low Back Pain The natural history of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy in most patients is for improvement within the first 4 weeks with noninvasive management1,2 There is no compelling evidence that routine imaging effects treatment decisions or improves outcomes3 For prolapsed lumbar disc with persistent radicular symptoms despite noninvasive therapy, discectomy or epidural steroids are potential treatment options4-8 Surgery is also a treatment option for persistent symptoms associated with spinal stenosis9-12 1. Vroomen PC, et al. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(475):119-123. 2. Weber H. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1983;8(2):131-140. 3. Modic MT, et al. Radiology. 2005;237(2):597-604. 4. Gibson JN, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000(3):CD001350. 5. Gibson JN, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005(4):CD001352. 6. Nelemans PJ, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26(5):501-515. 7. Peul WC, et al. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(22):2245-2256. 8. Weinstein JN, et al. JAMA. 2006;296(20):2451-2459. 9. Amundsen T, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(11):1424-1435. 10. Atlas SJ, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(8):936-943. 11. Weinstein JN, et al. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(22):2257-2270. 12. Malmivaara A, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(1):1-8. MRI for Low Back Pain MRI (preferred if available) or CT is recommended for evaluating patients with persistent back and leg pain who are potential candidates for invasive interventions Plain radiography cannot visualize discs or accurately evaluate the degree of spinal stenosis1 However, clinicians should be aware that findings on MRI or CT (such as bulging disc without nerve root impingement) are often nonspecific Recommendations for specific invasive interventions, interpretation of radiographic findings, and additional work-up beyond scope of guideline, but decisions should be based on clinical correlation between symptoms and radiographic findings, severity of symptoms, patient preferences, surgical risks, and costs and will generally require specialist input 2 1. Jarvik JG, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(7):586-597. 2. Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491. Critical Clinical Indicators of Pathology In patients with back and leg pain, a typical history for sciatica (back and leg pain in a typical lumbar nerve root distribution) has a fairly high sensitivity, but uncertain specificity for herniated disc1,2 >90% of symptomatic lumbar disc herniations (back and leg pain due to a prolapsed lumbar disc compressing a nerve root) occur at L4/L5 and L5/S1 levels3 1. van den Hoogen HM, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(3):318-327. 2. Vroomen PC, et al. J Neurol. 1999;246(10):899-906. 3. Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491. Critical Clinical Indicators of Pathology (cont.) A focused examination that includes straight-leg-raise testing and a neurologic examination that includes evaluation of knee strength and reflexes (L4 nerve root), great toe and foot dorsiflexion strength (L5 nerve root), foot plantarflexion and ankle reflexes (S1 nerve root), and distribution of sensory symptoms should be done to assess the presence and severity of nerve root dysfunction Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491. Critical Clinical Indicators of Pathology (cont.) A positive result on straight-leg-raise test (defined as reproduction of the patient’s sciatica between 30 and 70 degrees of leg elevation) has a relatively high sensitivity (91% [95% CI, 82% to 94%]), but modest specificity (26% [CI, 16% to 38%]) for diagnosing herniated disc Crossed straight-leg-raise test is more specific (88% [CI, 86% to 90%]), but less sensitive (29% [CI, 24% to 34%]) Deville WL, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(9):1140-1147. Critical Clinical Indicators of Pathology (cont.) All patients should be evaluated for Presence of rapidly progressive or severe neurologic deficits Motor deficits at more than 1 level, fecal incontinence, and bladder dysfunction Most frequent finding in cauda equina syndrome is urinary retention (90% sensitivity) Without urinary retention, probability is approximately 1 in 10,000 Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491. Deyo RA, et al. JAMA. 1992;268(6):760-765. Yellow Flags Identify psychosocial problems in acute phase Slow progress to recovery may be due to undetected, or unrevealed psychosocial factors Pertain to patient's beliefs and behaviors concerning physical activity and domestic, social, and vocational responsibilities Example: patient believes physical activity might harm back, make pain worse, so avoids activities Most destructive is aversion to work Belief that work caused pain, work aggravates pain, work is too heavy, and work should not be done McGuirk BE, et al. In: Ballantyne J, Fishman S and Bonica JJ, eds. Bonica's Management of Pain. 2010:1094-1105. Psychosocial Factors of Low Back Pain Stronger predictors of LBP outcomes than either physical findings or severity/duration of pain1-3 Assessment of psychosocial factors identifies patients who may have delayed recovery and could help target interventions 1 trial in referral setting found intensive multidisciplinary rehabilitation more effective than usual care in patients with acute or subacute LBP identified as having risk factors for chronic back pain disability4 Direct evidence on effective primary care interventions for identifying and treating such factors in patients with acute LBP is lacking5,6 Evidence is currently insufficient to recommend optimal methods for assessing psychosocial factors and emotional distress7 However, psychosocial factors that may predict poorer LBP outcomes include presence of depression, passive coping strategies, job dissatisfaction, higher disability levels, disputed compensation claims, or somatization8-10 1. Pengel LH, et al. BMJ. 2003;327(7410):323. 2. Fayad F, et al. Ann Readapt Med Phys. 2004;47(4):179-189. 3. Pincus T, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27(5):E109-120. 4. Gatchel RJ, et al. J Occup Rehabil. 2003;13(1):1-9. 5. Hay EM, et al. Lancet. 2005;365(9476):2024-2030. 6. Jellema P, et al. BMJ. 2005;331(7508):84. 7. Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491. 8. Steenstra IA, et al. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62(12):851-860. 9. Deyo RA, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(23):2724-2727. 10. Carey TS, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21(3):339-344. Red Flags of Lower Back Pain History Physical Examination Gradual onset of back pain Age <20 years or >50 years Thoracic back pain Pain lasting longer than 6 weeks History of trauma Fever/chills/night sweats Unintentional weight loss Pain worse with recumbency Pain worse at night Unrelenting pain despite supratherapeutic doses of analgesics History of malignancy History of immunosuppression Recent procedure causing bacteremia History of intravenous drug use Winters ME, et al. Med Clin North Am. 2006;90(3):505-523. Fever Hypotension Extreme hypertension Pale, ashen appearance Pulsatile abdominal mass Pulse amplitude differentials Spinous process tenderness Focal neurologic signs Acute urinary retention Risk for Chronicity Vertebral infection Intravenous Vertebral drug use, recent infection compression fracture Older age, history of osteoporosis, and steroid use Musculoskeletal Inactivity In general Emotional distress Cancer-Related Risk Factors Large, prospective study from a primary care setting History of cancer (positive likelihood ratio, 14.7) Unexplained weight loss (positive likelihood ratio, 2.7) Failure to improve after 1 month (positive likelihood ratio, 3.0) Age >50 years (positive likelihood ratio, 2.7) Posttest probability of cancer increases from approximately 0.7% to 9% in patients with a history of cancer (not including nonmelanoma skin cancer) In patients with any 1 of the other 3 risk factors, the likelihood of cancer only increases to approximately 1.2% Deyo RA, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(3):230-238. Non-Cancer-Related Risk Factors Features predicting vertebral infection not well studied, but may include fever, intravenous drug use, or recent infection1 Consider risk factors for vertebral compression fracture, such as older age, history of osteoporosis, and steroid use; and for ankylosing spondylitis, such as younger age, morning stiffness, improvement with exercise, alternating buttock pain, and awakening due to back pain during the second part of the night only2 Clinicians should be aware that criteria for diagnosing early ankylosing spondylitis (before the development of radiographic abnormalities) are evolving3 1. Jarvik JG, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(7):586-597. 2. Rudwaleit M, et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(2):569-578. 3. Rudwaleit M, et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(4):1000-1008. Racial/Cultural Aspects of Assessment To communicate effectively with all patients Always use simple words, not medical jargon Determine what the patient/caregiver already knows or believes about his/her health situation Encourage questions by asking, “What questions do you have?” (allows for an openended response), instead of “Do you have any questions?” (allows for a “no” response, ending the conversation) Use the “teach-back” method to confirm the level of understanding: Ask patients/family members to restate what was just communicated in the appointment or meeting Zacharoff KL. Cross-Cultural Pain Management: Effective Treatment of Pain in the Hispanic Population; 2009. Culturally Competent Care Ensure that patients/consumers receive effective, understandable, and respectful care that is provided in a manner compatible with their cultural health beliefs and practices and preferred language Implement strategies to recruit, retain, and promote at all levels of the organization a diverse staff and leadership that are representative of the demographic characteristics of the service area Ensure that staff, at all levels and across all disciplines, receives ongoing education and training in CLAS delivery USDHHS OMH. National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) in Health Care; 2001. Avoiding Racial and Cultural Bias per Knox H. Todd, MD, MPH Make Give pain assessment mandatory a nonopioid analgesic at triage Track reasons for unscheduled returns Audit for ethnic bias Consider which pain scales should be used Use multilingual laminated cards Todd KH. Medical Ethics Advisor. 1999. Pearls for Practice Categorize patients into 1 of 3 broad groups: nonspecific low back pain, back pain potentially associated with radiculopathy or spinal stenosis, or back pain potentially associated with another specific spinal cause Evaluate psychosocial risk factors to predict the risk for chronic, disabling low back pain Provide patients with evidence-based information on expected course of low back pain, effective self-care options, and recommend that they be physically active Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491. Questions? Please pass your question card to a staff member. Treatment of Low Back Pain: Pharmacologic and Nonpharmacologic Options Roger Chou, MD, FACP Associate Professor of Medicine, Department of Medicine Department of Medical Informatics and Clinical Epidemiology Oregon Health & Science University Disclosure: Roger Chou, MD, FACP Dr. Chou has disclosed that he has no actual or potential conflict of interest in regard to this activity His presentation will include off-label discussion of anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, and tricyclic antidepressants for the treatment of low back pain (LBP) Learning Objective Integrate evidence-based pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies into a comprehensive treatment plan for chronic LBP Low Back Pain Burden LBP is the fifth most common reason for US office visits, and the second most common symptomatic reason1-2 $90.7 billion dollars in total healthcare expenditures in 19983 LBP is the most common cause for activity limitations in persons under the age of 454 1. Hart LG, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(1):11-19. 2. Deyo RA, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(23):2724-2727. 3. Luo X, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29(1):79-86. 4. Von Korff M, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21(24):2833-2837. Increasing Rates of Back Surgery US Average Rate of Discharges per 1000 Medicare Enrollees Trends in Rates of Discectomy/Laminectomy and Fusion in 1992-2003 Weinstein JN, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(23):2707-2714. Increasing Rates of Back Injections Lumbosacral Injection Rates by Year: Age- and Sex-Adjusted per 100,000 2055.2 553.4 79.7 SI=sacroiliac. Friedly J, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(16):1754-1760. 263.9 212.3 Mean ($) Increasing Costs Year Martin BI, et al. JAMA. 2008;299(6):656-664. Rising Prevalence of Chronic LBP Prevalence of Chronic Low Back Pain in North Carolina, 1992 and 2006 % Prevalence (95% CI) 1992: 3.9% Characteristic Total Sex Male Female Age (Years) 21-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65 Race/Ethnicity Non-Hispanic White Non-Hispanic Black Hispanic Other 2006: 10.2% 1992 (n=8067) 3.9 (3.4-4.4) 2006 (n=9924) 10.2 (9.3-11.0) % Increase 162 PRR (2.5-97.5% CI)* 2.62 (2.21-3.13) 2.9 (2.2-3.6) 4.8 (4.0-5.6) 8.0 (6.8-9.2) 12.2 (10.9-13.5) 176 154 2.76 (2.11-3.75) 2.54 (2.13-3.08) 1.4 (0.8-2.0) 4.8 (3.3-6.3) 4.2 (3.0-5.5) 6.3 (4.2-8.3) 5.9 (4.5-7.3) 4.3 (3.0-5.6) 9.2 (7.2-11.2) 13.5 (11.4-15.7) 15.4 (12.8-17.9) 12.3 (10.2-14.4) 201 92 219 146 109 3.01 (1.95-5.17) 1.92 (1.35-2.86) 3.19 (2.29-4.59) 2.46 (1.73-3.50) 2.09 (1.62-2.84) 4.1 (3.5-4.7) 3.0 (2.0-4.0) ** 4.1 (1.4-6.8) 10.5 (9.4-11.5) 9.8 (8.2-11.4) 6.3 (3.8-8.9) 9.1 (6.0-12.0) 155 226 2.55 (2.13-3.05) 3.26 (2.32-4.96) 120 2.20 (1.16-6.99) CI=confidence interval. PRR=prevalence rate ratio. *The PRRs and CI were estimated via bootstrapping; 97.5% CIs were reported rather than to assume normality. **Unable to estimate owing to scall cell count (n<5). Freburger JK, et al. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(3):251-258. Practice Patterns Spine surgery rates in the US are the highest in the world Rates in the US 5 times higher than in the UK 20-fold variation in fusion: 4.6 per 1000 in Idaho Falls to 0.2 per 1000 in Bangor, Maine Interventional therapies are also widely used Intradiscal electrothermal therapy estimated at 7000-10,000 annually 20-fold variation in epidural steroid injections: 104 per 1000 in Palm Springs to 5.6 per 1000 in Honolulu Deyo RA, et al. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;443:139-146. Weinstein JN, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(23):2707-2714. “7 Back Pain Breakthroughs: Are you hurting? Here’s help.” Reader’s Digest July 2007 End Back Pain Agony (Michael J. Weiss) Weiss MJ. Reader's Digest. July, 2007. Reader’s Digest “Cures” for Low Back Pain “Cures” based on anecdotal evidence, not yet approved, and/or only in animal studies Infrared belt: $2335 “Magic Spinal Wand” Percutaneous automatic discectomy Flexible fusion Stem cells Site-directed bone growth New bed Based on an unpublished observational study funded by a sleep products trade group Weiss MJ. Reader's Digest. July, 2007. Low Back Pain Guidelines Project Overview and Timeline Began 2004; primary care guidelines published October 2007 Address both acute and chronic LBP, and nonspecific LBP and LBP with radiculopathy or spinal stenosis Guideline for interventional therapies/surgery published May 2009 Partnership between the American Pain Society and the American College of Physicians (ACP) Funded by the American Pain Society Multidisciplinary panel with 25 members; over 15 specialties/organizations represented Series of 3 face-to-face meetings to develop guidelines Consensus achieved for all recommendations Recommendation Grid ACP Methods Strength of Recommendation Quality of Evidence Benefits Do or Do Not Clearly Outweigh Risks Benefits and Risks and Burdens Finely Balanced High Strong Weak Moderate Strong Weak Low Strong Weak Insufficient Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491. I Basic Principles of Selecting Therapy for Low Back Pain For most LBP, labeling with a specific etiology doesn’t help inform therapy choices Most patients with acute LBP will improve regardless of which therapy is chosen For chronic LBP, therapies are moderately effective at best Use interventions with proven efficacy Noninvasive approaches to most LBP Consider psychosocial factors Recommendation Treatment of Low Back Pain Provide patients with evidence-based information about their expected course, advise patients to remain active, and provide information about effective self-care options Strong recommendation Moderate-quality evidence Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491. Advice and Self-Care for Low Back Pain Inform patients of generally favorable prognosis of acute LBP with or without sciatica Discuss need for re-evaluation if not improved Advise to remain active Consider self-care education books Superficial heat moderately effective for acute LBP No evidence to support use of lumbar supports Firm mattresses inferior to medium-firm mattresses (1 RCT) RCT=randomized controlled trial. Recommendation Treatment of Low Back Pain Consider the use of medications with proven benefits in conjunction with back care information and self-care … for most patients, first-line medication options are acetaminophen or NSAIDs Strong recommendation Moderate-quality evidence NSAIDs=nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491. Pharmacologic Interventions Drug Net Benefit Level of Evidence Acetaminophen Small to moderate Fair Skeletal muscle relaxants Moderate (for acute LBP only) Good Moderate Good Small to moderate (for chronic LBP only) Good NSAIDs Tricyclic antidepressants Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491. Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):505-514. This information includes a use that has not been approved by the US FDA. Pharmacologic Interventions (cont.) Drug Net Benefit Level of Evidence Opioids and tramadol Moderate Fair Benzodiazepines Moderate Fair Small (for radiculopathy only) Fair No benefit Good Antiepileptic medications Systemic steroids Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491. Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):505-514. This information includes a use that has not been approved by the US FDA. Recommendation Treatment of Low Back Pain For patients who do not improve with self-care options, consider the addition of nonpharmacologic therapy with proven benefits For chronic or subacute LBP, options include Intensive interdisciplinary rehabilitation Exercise therapy Acupuncture Massage therapy Spinal manipulation Yoga Cognitive-behavioral therapy Progressive relaxation Weak recommendation Moderate-quality evidence Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478-491. Noninvasive Interventions for Chronic or Subacute LBP Intervention Net Benefit Level of Evidence Behavioral therapy Moderate Good Exercise therapy Moderate Good Spinal manipulation Moderate Good Acupuncture Moderate Fair Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):492-504. Noninvasive Interventions for Chronic or Subacute LBP (cont.) Intervention Net Benefit Level of Evidence Massage Moderate Fair Yoga Moderate Fair (for Viniyoga) Small Fair No benefit Fair Unclear Poor Back schools Traction Interferential therapy, lumbar supports, short-wave diathermy, TENS, ultrasound TENS=transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. Chou R, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):492-504. Recommendation Interventional Therapies for Nonradicular Low Back Pain In patients with persistent nonradicular LBP, facet joint corticosteroid injection, prolotherapy, and intradiscal corticosteroid injection are not recommended Strong recommendation Moderate-quality evidence There is insufficient evidence to adequately evaluate benefits of other interventional therapies for nonradicular LBP Chou R, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(10):1066-1077. Interventional Therapies for Nonradicular Low Back Pain Interventional therapies not proven to be effective in placebo-controlled, randomized trials No trials (SI joint injection), trials showing no benefit (facet joint injection), inconsistent results (IDET, RFDN), or poor-quality evidence (trigger point injections) Promising results from nonrandomized studies not replicated in randomized trials IDET Facet joint steroid injection Not clear if interventions are ineffective, or if patients were not accurately selected IDET=intradiscal electrothermal therapy. RFDN=radiofrequency denervation. Chou R, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(10):1066-1077. Placebo-Controlled Trials of RFDN for Presumed Facet Joint Pain Sample Size Selection Quality Benefits Gallagher, 1994 41 Uncontrolled block Poor quality Can’t tell Leclaire, 2001 70 Uncontrolled block No major issues No Nath, 2008 40 Controlled block Baseline differences (1.6 points for pain) 1.5 points for leg pain, NS for back pain Tekin, 2007 60 Clinical criteria Poor quality <1 point for pain, 0.5 points for function van Kleef, 1999 30 Uncontrolled block No major issues 1-2 point for pain and function van Wijk, 2005 81 Uncontrolled block Technical issues? No Study NS=not significant. Placebo-Controlled Trials of RFDN for Presumed Facet Joint Pain Sample Size Selection Quality Benefits Gallagher, 1994 41 Uncontrolled block Poor quality Can’t tell Leclaire, 2001 70 Uncontrolled block No major issues No Nath, 2008 40 Controlled block Baseline differences (1.6 points for pain) 1.5 points for leg pain, NS for back pain Tekin, 2007 60 Clinical criteria Poor quality <1 point for pain, 0.5 points for function van Kleef, 1999 30 Uncontrolled block No major issues 1-2 point for pain and function van Wijk, 2005 81 Uncontrolled block Technical issues? No Study Placebo-Controlled Trials of RFDN for Presumed Facet Joint Pain (cont.) Study Leclaire, 2001 Sample Size Selection Quality Benefits 70 Uncontrolled block No major issues No 1.5 points for leg pain, NS for back pain 1-2 point for pain and function Nath, 2008 40 Controlled block Baseline differences (1.6 points for pain) van Kleef, 1999 30 Uncontrolled block No major issues Recommendation Surgery for Nonradicular Low Back Pain In patients with nonradicular LBP, common degenerative spinal changes, and persistent and disabling symptoms … discuss risks and benefits of surgery as an option Weak recommendation High-quality evidence Chou R, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(10):1066-1077. Surgery for Nonradicular Low Back Pain With Degenerative Changes Benefits vary depending on comparator Benefits of fusion vs standard nonsurgical therapy less than 15 points on a 100-point pain or function scale (1 RCT) No difference vs intensive interdisciplinary rehabilitation (3 RCTs) All enrollees failed >1 year of nonsurgical management and are not at higher risk for poor surgical outcomes Fewer than half experience optimal outcomes (relief of pain, return to work, decreased analgesic use) No evidence that instrumentation improves outcomes Shared decision-making approach recommended Chou R, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(10):1066-1077. Chou R, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(10):1094-1109. Recommendation Interventional Therapies for Radicular LBP In patients with persistent radiculopathy due to herniated lumbar disc … discuss risks and benefits of epidural steroid injection as an option Weak recommendation Moderate-quality evidence Chou R, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(10):1066-1077. Interventional Therapies for Radiculopathy/Prolapsed Disc Epidural steroid injection Short-term benefits in some higher-quality trials, but data are inconsistent (could be related to comparator used in trials) No long-term benefits No route clearly superior Limited evidence of no benefit for spinal stenosis Shared decision-making approach recommended Chou R, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(10):1066-1077. Recommendation Surgery for Radicular Low Back Pain and Spinal Stenosis In patients with persistent radiculopathy due to herniated lumbar disc or persistent and disabling leg pain due to spinal stenosis … discuss risks and benefits of surgery as an option Strong recommendation High-quality evidence Chou R, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(10):1066-1077. Surgery for Herniated Disc With Radiculopathy Discectomy associated with more rapid improvement in symptoms than nonsurgical therapy Patients improved either with or without surgery No progressive neurologic deficits without immediate surgery Long-term (after 1-2 years) outcomes similar in some trials Most trials evaluated standard open discectomy or microdiscectomy Shared decision-making approach recommended Chou R, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(10):1066-1077. Chou R, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(10):1094-1109. Surgery for Spinal Stenosis Decompressive laminectomy associated with superior outcomes vs nonsurgical therapy Mild improvement with nonsurgical therapy No severe neurologic deficits without immediate surgery Benefits may diminish with long-term (>2 years) follow-up Shared decision-making approach recommended Chou R, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(10):1066-1077. Chou R, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(10):1094-1109. Conclusions The quality of evidence for different LBP therapies varies A number of therapies appear similarly and moderately effective for LBP Guidelines can provide clinicians with a useful framework for choosing therapies Factors that influence choices from recommended therapies include patient preferences, availability, and costs Shared decision-making can help make decisions consistent with patient values and preferences Questions? Please pass your question card to a staff member. Current Understanding of the Prevention of Chronicity of Low Back Pain Bill McCarberg, MD Founder, Chronic Pain Management Program Kaiser Permanente San Diego Adjunct Assistant Clinical Professor, University of California, San Diego Disclosure: Bill McCarberg, MD Type Company Speakers Bureau Abbott Laboratories; Cephalon, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; Endo Pharmaceuticals; Forest Pharmaceuticals; King Pharmaceuticals; Ligand Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Merck & Co., Inc.; Mylan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Pfizer, Inc.; PriCara, Division of Ortho-McNeil-Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Purdue Pharma LP Dr. McCarberg’s presentation will not include discussion of off-label, experimental, and/or investigational uses of drugs or devices Learning Objective Evaluate early interventions for acute back pain in patients considered at high risk for transition to chronic low back pain (CLBP) Disability from Back Pain The minority of cases which involve disability account for a disproportionate percentage of overall healthcare costs The most cost-effective approach is to more aggressively pursue secondary prevention efforts on subacute patients before chronic disability is fully established1 Acute: <3 weeks Subacute: >3 weeks but <3 months Chronic: >3 months, or more than 6 episodes in 12 months 1. Waddell G, et al. Occup Med (Lond). 2001;51(2):124-135. Adverse Prognostic Indicators Yellow flags are psychosocial indicators suggesting increased risk of progression to long-term distress, disability, and pain Can be applied more broadly to assess likelihood of development of persistent problems from acute pain presentation Yellow flags can relate to the patient’s attitudes and beliefs, emotions, behaviors, family, and workplace Kendall NA. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 1999;13(3):545-554. Risk Factors for Chronic Low Back Pain: Yellow Flags Belief that pain and activity are harmful “Sickness behavior” such as extended rest Bodily preoccupation and catastrophic thinking Low or negative mood, anxiety, social withdrawal Personal problems (eg, marital, financial, etc) History of substance abuse Problems/dissatisfaction with work (“blue flags”) Overprotective family/lack of support History of disability and other claims Inappropriate expectations of treatment Low expectation of active participation The presence of yellow flags highlights the need to address specific psychosocial factors as part of a multimodal management approach Additional Risk Factors for Chronicity Previous history of low back pain Age Nerve root involvement Poor physical fitness Self-rated health poor Heavy manual labor, inability for light duty upon return to work (“black flags”) Ongoing medico-legal actions Obesity* Smoking* *No evidence for efficacy of smoking cessation or nonoperative weight loss as interventions for CLBP. Wai EK, et al. Spine J. 2008;8(1):195-202. Interventional Therapies Do Not Prevent Chronicity Level of Evidence and Summary Grades for Interdisciplinary Rehabilitation, Injections, Other Interventional Therapies, and Surgery for Patients With Nonradicular LBP Intervention Condition Level of Evidence Net Benefit Grade Interdisciplinary rehabilitation Nonspecific LBP Good Moderate B Prolotherapy Nonspecific LBP Good No benefit D Intradiscal steroid injection Presumed discogenic pain Good No benefit D Fusion surgery Nonradicular LBP with common dengerative changes Fair Moderate vs standard nonsurgical therapy, no difference vs intensive rehabilitation B Facet joint steroid injection Presumed facet joint pain Fair No benefit D Botulinum toxin injection Nonspecific LBP Poor Unable to estimate I Local injections Nonspecific LBP Poor Unable to estimate I Epidural steroid injection Nonspecific LBP Poor Unable to estimate I Medial branch block (therapeutic) Presumed facet joint pain Poor Unable to estimate I Sacroiliac joint steroid injection Presumed sacroiliac joint pain Poor Unable to estimate I Additionally, regardless of the comparator intervention, there is no convincing evidence that epidural steroids are associated with long-term benefits or reduced rates of subsequent surgery Chou R, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(10):1066-1077. The Fear-Avoidance Model of Chronic Pain Injury Disuse Disability Depression Recovery Avoidance Escape Pain Anxiety Hypervigilance Confrontation Pain Experience Fear of Pain Threat Perception Catastrophizing Negative Affectivity Threatening Illness Information Leeuw M, et al. J Behav Med. 2007;30(1):77-94. Vlaeyen JW, et al. Pain. 2000;85(3):317-332. Low Fear Assessment of Fear-Avoidance Behaviors Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS)1 Fear of Pain Questionnaire (FPQ)2 30 items Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ)3 13 items 16 items Coping Strategies Questionnaire (CSQ)4 42 items 1. Sullivan MJL, et al. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7(4):524-532. 2. McNeil DW, et al. J Behav Med. 1998;21(4):389-410. 3. Waddell G, et al. Pain. 1993;52(2):157-168. 4. Rosenstiel AK, et al. Pain. 1983;17(1):33-44. Reducing Catastrophizing Numerous interventions appear effective Cognitive-behavioral therapies1-4 Physiotherapy and other activitybased interventions5 Intensive patient education and exposure interventions6, 7 Limited understanding of the mechanisms by which changes in catastrophizing occur 1. Linton SJ, et al. Pain. 2001;90(1-2):83-90. 2. Basler HD, et al. Patient Educ Couns. 1997;31(2):113-124. 3. Vlaeyen JW, et al. Pain Res Manag. 2002;7(3):144-153. 4. Hoffman BM, et al. Health Psychol. 2007;26(1):1-9. 5. Smeets RJ, et al. J Pain. 2006;7(4):261-271. 6. Moseley GL, et al. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(5):324-330. 7. Leeuw M, et al. Pain. 2008;138(1):192-207. Comprehensive Interventions With High-Risk Patients Show Promise High-risk patients identified with SCID Intensive interdisciplinary team intervention 4 major components: psychology, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and case management Physical therapy sessions: both individual and group exercise classes Biofeedback/pain management sessions Group didactic sessions Case manager/occupational therapy sessions Interventions spaced over a 3-week period SCID=Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders. Gatchel RJ, et al. J Occup Rehabil. 2003;13(1):1-9. Early Intensive Intervention Effectiveness Long-Term Outcome Results at 12-Month Follow-Up HR-I (n=22) HR-NI (n=48) LR (n=54) p-Value % return to work at follow-up* 91% 69% 87% .027 Average number of healthcare visits regardless of reason** 25.6 28.8 12.4 .004 Average number of healthcare visits related to LBP** 17.0 27.3 9.3 .004 Average number of disability days due to back pain** 38.2 102.4 20.8 .001 Average of self-rated most “intense pain” at 12-month follow-up (0-100 scale)** 46.4 67.3 44.8 .001 Average of self-rated pain over last 3 months (0-100 scale)** 26.8 43.1 25.7 .001 % currently taking narcotic analgesics* 27.3% 43.8% 18.5% .020 % currently taking psychotropic medication 4.5% 16.7% 1.9% .019 Outcome Measure *Chi-square analysis. **ANOVA. HR-I=high-risk intervention group. HR-NI=high-risk nonintervention group. LR=low-risk group. Gatchel RJ, et al. J Occup Rehabil. 2003;13(1):1-9. Most Recent Preventing Chronicity Study (April 2009) First-onset, subacute LBP patients Behavioral medicine intervention (n=34) Four 1-hour individual treatment sessions included Education about back function and pain Systematic graduated increases in physical exercise to quota with feedback Planning and contracting activities of daily living Self-management and problem-solving training to cope with pain Contingent reinforcement of active functioning and nonreinforcement of pain behaviors Vocational counseling, as needed Compared to “attention control” group (n=33) Slater MA, et al. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(4):545-552. Most Recent Preventing Chronicity Study (April 2009) (cont.) Chi square analysis comparing proportions recovered at 6 months after pain onset for behavioral medicine and attention control participants found rates 54% vs 23% for those completing all 4 sessions and 6-month follow-up (p=.02) Conclusions: early intervention using a behavioral medicine rehabilitation approach may enhance recovery and reduce chronic pain and disability in patients with first-onset, subacute LBP Slater MA, et al. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(4):545-552. Key Impact Factors in Back Disability Prevention Spread of Rankings for Impact Provided by Key Stakeholders (N=33) at the End of a Consensus Process (Round 3) 1. Provider Reassurance } p=.055 2. Recovery Expectation } p=.045 3. Fears 4. Knowledge 5. Appropriate Care 6. Disability Management 7. Self-Management 8. Case Management 9. Temporary Duties } p<.001 10. Alternative Care } p<.001 11. Back Supports 0 2 4 6 Rankings by Panel Guzman J, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(7):807-815. 8 10 12 Provider Reassurance Tell patients your plan and your expectations Set reasonable expectations with patient buy-in Reassure severity of acute pain does not correlate with outcome or duration Follow up regularly to check response to treatment Reassess for further diagnostic of therapeutic options Summary Psychosocial aspects of pain and pain perception significantly influence patient outcomes Assessing for yellow flags and identifying patients at high risk of chronicity early in pain process (subacute) yields best chance for intervention and possible prevention Multiple psychosocial and physical interventions appear promising; aggressive/ intensive intervention seems most important Nurture the therapeutic relationship with shared expectations and goals of treatment Questions? Question and Answer Session Thank You for Attending Low Back Pain: Evaluation, Management, and Prognosis