Syllabus - Campbell County Schools

advertisement

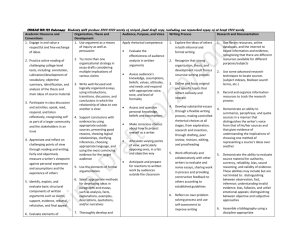

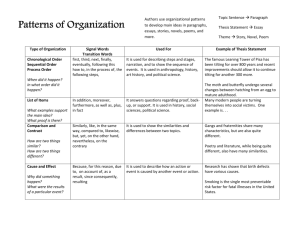

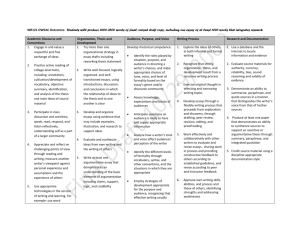

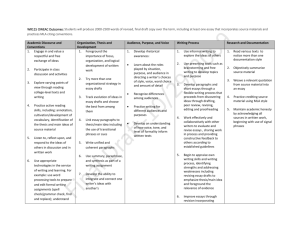

AP® English Language & Composition Syllabus Instructor: Toni DeJaco McKee Phone: 859-635-4161 x1161 Email: toni.mckee@campbell.kyschools.us Course Overview In this introductory college-level course students read and analyze carefully a wide and challenging selection of both nonfiction prose and fiction with the purpose of deepening their understanding of rhetoric and the power of language. By reading closely and writing often, students will develop the ability to use language and create text with an increased awareness of purpose and strategy, while improving their own composing abilities. Composition is approached as a multi-tasked process requiring several stages or drafts, with revision aided by peer editing and teacher review. Students practice different revision techniques, including layering, visualization, switching genres, using concrete and memory-soaked words, and trying different leads and conclusions. As students write in a variety of modes for a variety of audiences, they develop a personal style and the ability to analyze and explicate how the elements of language work in any particular text. Also, given that students exist in an extremely visual world, we analyze how graphics and visual images such as films, advertisements, photographs, comic strips, posters, tables, paintings, and sculpture relate to written texts and serve as alternative forms of text themselves. This course teaches students to read both primary and secondary sources carefully, in order to synthesize information from those sources in their own compositions, and to cite them using the conventions of a professional organization such as the Modern Language Association (MLA). Readings in the course feature expository, analytical, personal, and argumentative works from a variety of authors and historical contexts. Students study and work with essays, letters, speeches, images, and imaginative literature. The purpose of this course is to help students “write effectively and confidently in their college courses across the curriculum and in their professional and personal lives.” (The College Board, AP® English Course Description) In addition, the course is organized according to the requirements and guidelines of the current AP English Course Description, and, therefore, students are expected to read critically, think analytically, and communicate clearly both in writing and speech. Throughout the course students prepare for the AP® English Language and Composition Exam and may be granted advanced placement, college credit, or both as a result of satisfactory performance. Student Evaluation Grading is viewed in the context that student thinking, writing, reading, listening, and speaking are central to class activity. Throughout the class I continually evaluate student performance and progress, by assessing student work in papers, in-class participation, homework, and daily preparation. My goal is to help students to become more capable and confident with selfassessment. Essays 40%: Formal essays are often drafted in class and graded as rough drafts. Rough drafts are first self-edited and peeredited before students create a final draft for teacher review. These final drafts make up 40 percent of the term grade. Rough drafts and editing assignments are part of daily work, which is 20 percent of the term grade. All drafts and graded final drafts are kept in a portfolio that counts as part of the final exam grade for the term. The AP sliding scale rubric will be used in grading these papers. Exams & Quizzes 30%: Most exams consist of multiple-choice questions based on rhetorical devices and their function in given passages. Some passages are from texts read and studied, but some passages are from new material that students analyze for the first time. Many quizzes are used primarily to check for reading and basic understanding of a text. Weekly vocabulary quizzes are given from a list of words used on the SAT. Also, throughout each unit quizzes are given on grammatical and mechanical concepts reviewed in warm-up or anticipatory tasks as well as from our discussions and annotations of syntax from the readings. Daily/ Homework 30%: Daily assignments consist of a variety of tasks. These include prewriting, drafting, and editing exercises. Other daily tasks consist of grammar, vocabulary exercises, annotation of texts, and some fluency writing. Some homework may be graded on a “pop” grading method, meaning every little assignment may not be graded but you should always prepare them as if they were in case those are collected for me to review. This is mostly for those occasions where you have been asked to annotate or answer questions in your text book in order to prepare for the following in class lessons. Daily warm-up or anticipatory tasks begin most lessons. These exercises primarily focus on grammatical or writing concepts that relate to the day's reading assignment. (Concepts and ideas for these mini-lessons are taken from ACT® and SAT® Preparation booklets and McDougal-Littell Language Network Grammar Text.) Students complete these exercises during the first five to ten minutes of the class period. Grade System The following descriptions are adapted from an actual university catalog and reflect the explanations associated with letter grades. These are the descriptors that I will be using when creating rubrics for grading all work. (Notice that nowhere does it state that “simply completing all work constitutes an A.”) A : represents exceptionally high achievement as a result of aptitude, effort, and intellectual initiative. B : represents high achievement as a result of ability and effort. C : represents average achievement, the minimum grade expected of a college bound student D : represents the minimum passing grade F : indicates failure on an assignment or course; not demonstrating level of skill necessary for the college level Academic Integrity I expect that students think for themselves and do their own work. All forms of cheating and plagiarism will result in the student receiving a zero on the assignment, essay, test, quiz, project or presentation.. All student work must be your own. Plagiarism or copying another’s words without citing the source is not allowed. Within my class, that means that any form of plagiarism, be it from another student, a book, or a source on the Internet is not allowed. We will use the MLA definition of plagiarism, which defines plagiarism as the use of another’s words or ideas without proper citation. In other words, as soon as a student uses an idea or word(s) that is not his/her own, he/she must give the author of the idea/word(s) credit through proper MLA citation or is in violation of the academic integrity policy. Teaching Strategies Close Reading Deep, thoughtful, and reflective reading is essential to developing the strong rhetorical skills needed in college writing. By recognizing an author's choices when using generalization and specific illustrative detail, as well as other rhetorical traits, students become aware of such choices in their own writing. Students exercise close reading by producing descriptive outlines, using Kenneth A. Bruffee's "says/does" analyses, completing close reading responses, annotating copies of assigned texts, and writing in double-entry notebooks. Vocabulary Students will work to gain an enhanced vocabulary and practice using new terms in context in order to develop and use appropriately a wide-ranging vocabulary. To encourage an expanded vocabulary students are given a list of words most commonly found on the SAT. Each month a quiz on up to thirty words is given, testing the students’ ability to use the word in context and with the correct connotation by writing original sentences. Students use diction appropriately for a college-level audience, “including the avoidance of slang and clichés and the ability to use synonyms when necessary to avoid repetition.” (The College Board, AP® English Course Description) Journal or Writer’s Notebook (Double-entry Notebook) Students will be required to have some kind of written storehouse for ideas. For many this will take the form of a journal or writer's notebook. It may be kept in a composition or one-subject notebook. Other students may choose to keep an electronic journal, which of course they will later print for teacher review. This allows students to reflect deeply on the course readings with occasion to use a double-entry notebook for a more detailed examination of a particular reading. Also, students will use a notebook or journal to record personal experiences for their own writing projects. This is especially helpful for an early personal reflective essay. Informal Writing Informal writing includes writing dialogue to create a conversation with an author of an assigned text, writing letters to an author or to a character in a text of fiction, writing a list of key ideas for a class discussion, writing to imitate an author’s style, writing collaboratively, writing to generate ideas quickly (quick-writes or free writing), rewriting paragraphs, writing and rewriting a portion of an essay (introduction, body, or conclusion), practicing thesis statements, and writing in-class responses. Portfolios/ Binders A collection of journal writings, rough drafts, editing assignments, graded final copies, plans, research, and other daily tasks consisting of grammar reviews, vocabulary exercises, annotation of texts, and fluency writing are all kept in a portfolio turned in twice a term. Many of these activities have been discussed, shared, and reviewed in class; therefore, there is no need to grade immediately every piece of writing or class assignment. Students then have convenient access to materials necessary for writing projects and for review before a quiz or exam. Analyzing Visual Arguments As described in the College Board, AP® English Course Description, this course "teaches students to analyze how graphics and visual images both relate to written texts and serve as alternative forms of text themselves." Each term's unit of study includes a visual text(s) students analyze by reading images, advertisements, paintings, and photographs. After completing a close reading of a visual text and often a written text, students write a short analysis of the visual text. Style Because style is crucial to developing writers' progress when grappling with purpose and audience, students review the use of phrases and clauses in order to create "a variety of sentence structures, including appropriate use of subordination and coordination." (The College Board, AP® English Course Description) After completing sentence-and-paragraph-imitation exercises, students highlight their use of subordination and coordination in their major essays. In addition, students are instructed in "an effective use of rhetoric, including controlling tone, establishing and maintaining voice, and achieving appropriate emphasis through diction and sentence structure." (The College Board, AP® English Course Description) Also, nonfiction reading selections are chosen “to give students opportunities to identify and explain an author’s use of rhetorical strategies and techniques…[and] how various effects are achieved by writers’ linguistic and rhetorical choices.” (The College Board, AP® English Course Description) Timed Essays Timed in-class essays are used throughout the course to familiarize students with the type of pressured writing necessary for the AP English Language and Composition Exam. Chosen topics are drawn from AP Released Exam free-response questions. Teacher-led instruction on analysis and interpretation accompanies each in-class essay. In addition, the use of balanced generalization and specific illustrative detail is stressed and modeled. This becomes the practice for all in-class timed essays as well as all formal essays. Students write a minimum of two timed essays each term. Discussion This course offers students many opportunities to collaboratively practice the rhetorical skills emphasized and taught, giving them opportunities to check their understanding and clarify their thinking. Engaging students in provocative and thoughtful discussions not only makes the principles taught more meaningful and applicable but is an excellent method for practicing in context vital critical thinking and persuasive discourse skills. As students learn to engage their peers in focused discussions using Socratic questioning and employing logical support, the discussions become less teacher-directed. AP Prep Sessions We have been extremely fortunate to qualify for the Advanced Kentucky initiative which provides additional support for AP students as well as incentives for participating in the AP curriculum. Because of this, there will be several Prep Sessions throughout the year to aide you in your studies. Please make note of the following dates and plan to attend: Saturday, December 3, 2011: Workshop on skills and concepts Saturday in January/ February (actual date TBA): Mock AP exam Saturday, March 24, 2011: Mock exam scores, break down, explanations Every Thursday: I will be available after school for additional help and support. If I feel you are struggling in a certain area of skills, I may ask you to stay. You always have the option of staying on your own as well if you feel you need additional help from me. Course Organization Fall Semester First Quarter: Course Orientation, AP Course Description, Class Rules and Responsibilities, Grading, Rhetorical Terms with definitions, Rhetorical Modes, Rhetorical Devices, and Close Reading Reading: from The Language of Composition by Renee H. Shea, Lawrence Scanlon, and Robin Dissin Aufses o Chapter 1 An Introduction to Rhetoric: Using the "Available Means" Key Elements of Rhetoric The Rhetorical Triangle Appeals to Ethos, Logos, and Pathos Visual Rhetoric Rhetoric in Literature Patterns of Development When Rhetoric Misses the Mark o CHAPTER 2 Close Reading: The Art and Craft of Analysis Analyzing Style Talking with the Text Annotation Dialectical Journal Graphic Organizer Close Reading a Visual Text From Analysis to Essay: Writing about a Close Reading Glossary of Selected Tropes and Schemes o CHAPTER 3 Synthesizing Sources: Entering the Conversation Types of Support Writers at Work The Relationship of Sources to Audience The Synthesis Essay Conversation Focus on Community Service Identifying the Issues: Recognize Complexity Formulating Your Position Incorporating Sources: Inform Rather than Overwhelm Unit 1: To what extent do our schools serve the goals of a true education? Argument: Using Personal Experience as Evidence Reading: 1984 by George Orwell or Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself “I Know Why the Caged Bird Cannot Read” by Francine Prose “Education” by Ralph Waldo Emerson “Superman and Me” by Sherman Alexie “Best in Class” by Margaret Talbot “A Talk to Teachers” by James Baldwin “School” by Kyoko Mori “The History Teacher” (poetry) by Billy Collins “Eleven” (fiction) by Sandra Cisneros Visual Text NEA, from Reading at Risk (tables) from Report of the Massachusetts Board of Education by Horace Mann “High School, an Institution Whose Time Has Passed” by Leon Botstein from The Liberal Arts in an Age of Info-Glut by Todd Gitlin Visual Text Spirit of Education (painting) by Norman Rockwell Writing: Students read 1984 or Fahrenheit 451 independently, analyzing the 10 most important “moments” of the novel through identification of the various resources we have discussed in class as well as by explaining how those resources help achieve the overall theme (purpose) of the text. While reading the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, students write at least six extended and thoughtful journal entries noting Douglass’s intellectual progress and awareness. In addition, this term students will choose two texts written at least 30 years apart and collaboratively study the diction, sentence structure, and tone of the writers. This allows students to study and then use in their own writing a variety of sentence structures, including appropriate use of subordination and coordination. Throughout the readings for this unit students note observations in a writer’s journal about the role of education from multiple perspectives to be used for a personal narrative reflecting on their own education experience and how that experience mirrors and differs from views in the texts we have studied. Narrative organization such as chronological order and in medias res is modeled and practiced. In-class drafting, peer editing and teacher review will help students refine their thinking both before and after composing a final draft. Along with the journal writing, writer’s notebook, and personal narrative essay, students will write two timed essays from AP Released Exam free-response questions. Reading Visual Images: This term students examine in relation to the nonfiction readings a table from Reading at Risk or the Spirit of Education painting and write an analysis of what is revealed in the table or painting that cannot be conveyed as effectively in an essay. Second Quarter: Unit 2: How does our work shape or influence our lives? Close Reading: Analyzing style in Paired Passages, Accounting for Purpose, Deepening Appreciation of Rhetorical Strategies, and Intimations of Argument In Cold Blood by Truman Capote Or The Jungle by Upton Sinclair Of Mice and Men by John Stienbeck from Serving in Florida by Barbara Ehrenreich from “The Atlanta Exposition Address” by Booker T. Washington “The Surgeon as Priest” by Richard Selzer “Labour” by Thomas Carlyle “The Traveling Bra Salesman’s Lesson” by Claudia O’Keefe “The Stunt Pilot” by Annie Dillard “In Praise of a Snail’s Pace” by Ellen Goodman “I Stand Here Ironing” (fiction) by Tillie Olsen “Harvest Song” (poetry) by Jean Toomer Visual Text “We Can Do It!” (poster) by J. Howard Miller Visual Text “The Great GAPsby Society” (cartoon) by Jeff Parker “More Working Parents Play Beat the Clock” by Marilyn Gardner “Sick Parents Go to Work, Stay Home When Kids Are Ill” by Christopher Mele “Why Woman Have to Work” by Amelia Warrne Tyagi “My Mother, Myself, Her Career, My Questions” by Kimberly Palmer “Don’t Call Me Mr. Mom” by Buzz McClain Writing: Students read John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men independently, analyzing the 10 most important “moments” of the novel through identification of the various resources we have discussed in class as well as by explaining how those resources help achieve the overall theme (purpose) of the text. This particular novel is given an in-depth study, as students discuss symbolism, diction, foreshadowing, irony, similes, metaphors, and archetypes of the various characters and plot development. While reading In Cold Blood or The Jungle students write at least six thoughtful journal entries exploring the dynamic psychological thoughts and relationships of chosen characters with a focus on how their life experiences influenced their lives. As the many nonfiction essays are read and discussed, students write in a writer’s notebook about how the relationship of personality, gender, societal expectations, and personal experience influence our choice of work and how work influences our lives. Using class discussions, readings, journal and writer’s notebook entries, students write an expository essay explaining what influences most strongly determine our career choices. Logical organization is taught to enhance student writing “by specific techniques to increase coherence, such as repetition, transitions, and emphasis.” (The College Board, AP® English Course Description) In-class drafting, peer editing and teacher review will help students refine their thinking both before and after composing a final draft. Along with the journal writing, writer’s notebook, and expository essay, students will write two timed essays from AP Released Exam free-response questions. Beginning this quarter and extending into the third quarter, students will conduct research incorporating primary and secondary sources in which they write an I-search paper. Students are introduced to more unconventional forms of research, including photos, albums, films, and personal interviews. Students begin working on the I-Search paper, a personal research paper designed to help students personally find meaningful answers to questions. A thesis is organized and research is conducted in order to organize and support that thesis. Class discussions and lectures include plagiarism, primary and secondary citations, as well as the proper documentation within a works cited page. Reading Visual Images: After examining and discussing Howard Miller’s poster and Jeff Parker’s cartoon, students note the relationship of the text to the images and choose either the poster or cartoon to write a one-page analysis of how the text both adds and distracts from the power of the images. First Semester Exam At the end of the second quarter and first semester, students take an 80-minute exam featuring AP Multiple Choice questions and two AP free-response questions from released exams—one focuses on prose analysis and rhetoric, the other on argument. Spring Semester Third Quarter: Unit 3: What is the relationship of the individual to the community? Synthesis: Incorporating Sources into a Revision, Understanding and Developing Argument The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien “Letter from Birmingham Jail” by Martin Luther King Jr. “Eight Alabama Clergymen,” Public Statement from Walden, “Where I Lived, and What I Lived for” by Henry David Thoreau “In Search of the Good Family” by Jane Howard “The New Community” by Amitai Etzioni from “Being Perfect: Commencement Speech at Mt. Holyoke College” by Anna Quindlen “Walking the Path between Worlds” by Lori Arviso Alvord “Child of the Americas” (poetry) by Aurora Levins Morales Visual Text Reflections (painting) by Lee Teter Visual Text Three Servicemen (sculpture) by Frederick Hart “The Happy Life” by Bertrand Russell “The Singer Solution to World Poverty” by Peter Singer “Lifeboat Ethics: The Case against Helping the Poor” by Garrett Hardin Writing: Students read Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried independently, analyzing the 10 most important “moments” of the novel through identification of the various resources we have discussed in class as well as by explaining how those resources help achieve the overall theme (purpose) of the text. As students read The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the nonfiction selections for this term, they explore the unit’s theme of the relationship of the individual to the community by writing often in both their reading journal and writer’s notebook. Along with informal writing, class discussion and activities prepare students to write an analytical essay examining how current moral and racial tensions affect Bertrand Russell’s view of the “happy life.” Organizational strategies are emphasized such as using a specific and compelling thesis statement, the specificity of quotations, using parallelism, and appropriate transitions. In-class drafting, peer editing and teacher review will help students refine their thinking both before and after composing a final draft. Along with the journal writing, writer’s notebook, and analytical essay, students will write two timed essays from AP Released Exam free-response questions. Reading Visual Images: After reading “Walking the Path between Worlds” by Lori Arviso Alvord, students collaboratively explore the relationship between the essay and Lee Teter’s painting Reflections noting how the painting both relates to Alvord’s thesis and asserts a thesis of its own. In a one-page essay students analyze how the painting expresses its own thesis. Fourth Quarter: Unit 4: What is the impact of gender roles that society creates and enforces? Argument: Supporting an Assertion, Argumentative Research Project and Focused Preparation for the AP English Language and Composition Exam The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald “Women’s Brains” by Stephen Jay Gould “Professions for Women” by Virginia Woolf “Letters” by John and Abigail Adams “About Men” by Gretel Ehrlich “Being a Man” by Paul Theroux “AIDs Has a Woman’s Face” (speech) by Stephen Lewis “There is No Unmarked Woman” by Deborah Tannen “Sweat” (fiction) by Zora Neale Hurston “Barbie Doll” (poetry) by Marge Piercy Visual Text Cathy (cartoon) by Cathy Guisewite Visual Text “New and Newer Versions of Scripture” (table) by Bill Broadway “Mind over Muscle” by David Brooks Writing: Students read F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby independently, analyzing the 10 most important “moments” of the novel through identification of the various resources we have discussed in class as well as by explaining how those resources help achieve the overall theme (purpose) of the text. In a reading journal for The Scarlet Letter, students will identify an understanding of the following elements: characterization, setting, initial incidents, conflicts, climaxes, resolutions, and conclusions, as well as identify and comment on the rhetorical and stylistic choices that the author makes. For the nonfiction reading, students will note in their writer’s notebook specific illustrative details for supporting answers to the research paper questions. The final paper will be a research paper in which students develop a thesis based on their research for the questions: Who are the outsiders in our society? Why are they in this position? How does society treat them? Should society be more tolerant of them? Using at least five sources from this unit, including The Scarlet Letter, students write an essay that discusses the position of the outsider in society remembering to attribute both direct and indirect citations. Students must refer to the sources by authors’ last names or by titles and avoid mere paraphrase or summary. Students will synthesize the main ideas from both primary and secondary sources in support of their own thesis using MLA format. Through this exercise students will learn how to assess and choose sources. The paper will center on an original arguable thesis of the student’s choosing and will go through several revisions and a peer edit. Students will write sample thesis statements for group analysis, and then will compose assertions to best prove their chosen thesis statements. Organizing evaluated arguments and counter arguments will be taught. Persuasive techniques will be discussed and implemented. When students have a working thesis, they will conference with me on the direction they will take in their paper. Along with the journal writing, writer’s notebook, and argumentative research paper, students will write two timed essays from AP Released Exam free-response questions. Reading Visual Images: Using the Cathy cartoon students will compare and contrast its implied thesis with one of the nonfiction selections about women from this unit. Unit 5: American Drama: How has the use of rhetoric been used in American Drama to drive social commentary on controversial issues? Student will work in literature circles with the drama of their choice and focus on various aspects of American Drama. Options will include: A Raisin in the Sun, Death of A Salesman, A Streetcar Named Desire, The Glass Menagerie, The Man Who Came to Dinner, Out Town, and The Crucible Writing: Students will read the drama of their choice with their Literature groups and write various pieces associated with their particular play. Reading Visual Images: Students will view and perform specific scenes from their chosen dramas in order to demonstrate the uses of rhetoric in this particular genre. Unit 6: Career Finder. How can the effective use of rhetoric be relevant when searching for a career in my future? Various examples of cover letters Applications Resumés Writing: Students will create their own cover letter and resumés, then will interview with various professionals in their chosen fields in order to gain experience in using rhetoric (both written and oral). This will allow them to compete against other students applying for the same job. (Note: Units 5 and 6 will studied concurrently) No final exam for Spring Semester. Students take the AP English Language and Composition Exam, which substitutes for the final exam. Students who do not take the AP exam will have to take a final exam, they will not be exempt. References Bruffee, Kenneth A. A Short Course in Writing, 2 nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Winthrop, 1980. College Board. AP English Course Description. New York: The College Board, 2008. Glencoe Grammar and Composition Handbook Grade 11. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002. Hodges, John C. ed. Harbrace College Handbook. New York: Harcourt Brace College Publishers, 2008. Shea, Renee, Lawrence Scanlon, and Robin Dissin Aufses, The Language of Composition: Reading, Writing, Rhetoric. Boston: Bedford/St. Martins, 2008. Attribution: This syllabus was adapted from a syllabus created by Mr. Todd S. Roach, M.A. British and American Literature Note: This is a working syllabus and may change should it be deemed necessary. Class Procedures Students are accountable for all information and assignments; this means that it is imperative that students attend class each and every day. Excused Absence Students who miss class with an excused absence will have the opportunity to make up work missed for that day. They will have an equal number of days (not class meetings) as their absence to make up the work. It is the student’s responsibility to check his/her period's absence bin or see me for missed assignments before school, after school or at lunch. You may also check my teacher website. I WILL NOT PROVIDE ABSENT WORK DURING CLASS. Unexcused Absences Students who miss class with an unexcused absence will receive zero participation points for that day and are unable to make up missed work. Absences due to Extra Curricular or Sports Activities Students who miss class due to extracurricular or sports activities are accountable for all work. It is the student’s responsibility to see me regarding missed work as per the excused absence policy. Assignments due on days missed are still due that day, even if the student is not in class. It is his/her responsibility to turn the work in to me. Late work will not be accepted. Essays/Projects/Presentations All essays/projects/presentations are due on assigned due dates, regardless if the student is present in class. All assignments should be printed out, put together, and ready to hand in at the beginning of class the day it is due. I WILL NOT allow you to print off of my computer or go to the library the day that it is due! Classroom Rules " R-E-S-P-E-C-T: If students respect their teachers, their classroom, their fellow students, their studies, and ultimately, themselves, there will be no discipline problems in this class. " Hall pass Privileges These should be used with discretion. Please use common sense when asking permission to be in the hall for any reason. This is a privilege and I reserve the right to revoke this privilege should you abuse it. General rules and expectations 1. Be respectful: Do not talk while others are talking, no put downs or profanity 2. Be responsible: Be prepared for class, follow directions, be on task at all times 3. Be safe: Don’t throw objects, keep hands and feet to yourself, don’t allow bullying FINAL NOTE "Close the door. Write with no one looking over your shoulder. Don't try to figure out what other people want to hear from you; figure out what you have to say. It's the one and only thing you have to offer." -Barbara Kingsolver Finally, please allow me to extend an enthusiastic “welcome” to this class. I am looking forward to an exciting year of reading, writing, learning, sharing and growing together. Remember that in an AP course, the quality of the class is as dependent on your preparation and interest level as it is on mine. Remember to be self-motivated, hard working, and academically curious and we should all have a great year. If you have any questions, please contact me at your convenience by phone or email. Together, I hope we will enjoy this challenging course. Mrs. McKee The Extra Mile How to successfully survive Junior English! The Basics: If you participate in a sport or activity like Band, Choir, Dance, Music, Art, Drama, Academic team etc., typically, you want to perform at your best; you want to be in shape, perfect your moves, and be strong for your performances. Your brain should be no different. You should be just as willing to go the extra mile in order to be your best in the classroom. Sometimes, your coach, instructor, or director will give you extra practice to push you to get better and when they see your potential, they strive to challenge you. This is your “Extra Mile WorkOut” opportunity to insure you put on best performance in the classroom. I am your Coach! “The Extra Mile” will be held before or after school on Thursdays or during CLC/activity time (for anything like make-ups, catch-ups, behavior issues, writing help, organizational skills, etc.). The “Team” for that week’s WorkOut session will be noted on the whiteboard at the front of the room. If your name is on the board, your presence will be expected. Not completing homework assignments will NOT be tolerated. Extra Mile WorkOuts will be assigned. You can have your name removed from the WorkOut list by turning in your work prior to that WorkOut date. Either way, the late assignment will be worth 60%. If any zeroes are earned on a pop quiz, another will be given the next day over the same material. If a student received two zeroes in a row, Extra Mile WorkOut will be assigned. We’ll go over whether this is because of lack of notes, lack of full attention or effort, and/or lack of understanding. When it is clear that the student is focused on his/her learning of that particular material, zeroes will be erased and replaced with a 60% (as if it was a late homework assignment). On announced quizzes and tests, as well as other in-class assignments and writings, if 70% is not reached (what the state considers proficient work), you’ll receive a “not yet” note on your paper and will be assigned Extra Mile WorkOut to work on revising, adding to, bettering, etc. your grade. Again, it is possible to have your name removed from the WorkOut list by turning this in prior to that Extra Mile date. The idea here is to ensure you are mastering the content/skills. If a student is a “no-show” to WorkOuts, he/she will be automatically “On the Inactive Roster ” and a referral will be sent to “the Commissioner” (administration) in order to be reinstated to the “Active Roster” (Which means you will be written up and serve 2 detentions for missing your workout). Notes of Interest: “Time Out” can be granted from WorkOut with Camel Passes – given out as rewards periodically and randomly throughout the year. These will buy you 3 extra days to turn in work without deduction of any points. If an assignment is such that it really can’t be made up (untimely and/or a one-time thing), another will replace it (more than likely grammar and/or writing improvement practice). Others are welcome to join WorkOuts voluntarily. If you need help, don’t hesitate!! Bottom line of English III survival: Survival is easiest when you make the choice to form habits of Taking good notes, Asking questions for clarification, Reviewing notes on a consistent basis, Being responsible when you miss class for ANY reason, and Giving full effort on all assignments. These habits will make you a success not only this year in English but across your academic schedule and wherever your post-secondary path takes you!