NP i

advertisement

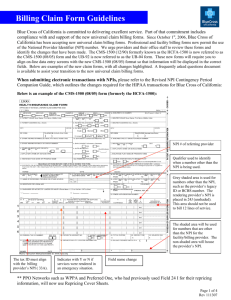

CAS LX 522 Syntax I Episode 4a. Binding Theory, NPIs, ccommand. 4.3 A mysterious pattern English (and most languages) have a couple of different ways to refer to individuals and entities. Johnj saw himselfj/*k. *Johnj saw herselfj/k. Johnj saw himk/*j. Johnj saw herk/#j. *Hek/*j saw Johnj. Hisj/k mother saw Johnj. Johnj thinks that Mary likes himj/k. *Johnj thinks that Mary likes himselfj/k. Johnj thinks that hej/k is a genius. *Johnj thinks that himselfj/k is a genius. When do you use anaphors (-self forms)? Pronouns? What determines the range of interpretations they can have? These are the questions Binding Theory strives to answer. Binding Theory Binding Theory consists of three Principles that govern the allowed distribution of NPs. Pronouns: he, her, it, she, … Anaphors: himself, herself, itself, … R-expressions: John, the student, … R-expressions and anaphors R-expressions are NPs like Pat, or the professor, or an unlucky farmer, which get their meaning by referring to something in the world. Most NPs are like this. An anaphor does not get its meaning from something in the world—it depends on something else in the sentence. John saw himself in the mirror. Mary bought herself a sandwich. Pronouns A pronoun is similar to an anaphor in that it doesn’t refer to something in the world but gets its reference from somewhere else. John told Mary that he likes pizza. Mary wondered if she agreed. …but it doesn’t need to be something in the sentence. Mary concluded that he was crazy. The problem There are very specific configurations in which pronouns, anaphors, and R-expressions can/must be used. Even though both he and himself could refer to John below, you can’t just choose freely between them. John saw himself. *John saw him. John thinks that Mary likes him. *John thinks that Mary likes himself. John thinks that he is a genius. *John thinks that himself is a genius. The question Binding Theory strives to answer is: When do you use anaphors, pronouns, and R-expressions? Indices and antecedents Anaphors and pronouns are referentially dependent; they can (or must) be coreferential with another NP in the sentence. The way we indicate that two NPs are coreferential is by means of an index, usually a subscripted letter. Two NPs that share the same index (that are coindexed) also share the same referent. Johni saw himselfi in the mirror. Indices and antecedents Johni saw himselfi in the mirror. An index functions as a “pointer” into our mental model of the world. John here is a name that “points” to our mental representation of some guy, John, which we notate by giving the pointing relation a label (“i”). himself here shares the same pointing relation, it “points” to the same guy John that John does. So, any two NPs that share an index (pointing relation) necessarily refer to the same thing. Indices and antecedents Johni saw himselfi in the mirror. The NP from which an anaphor or pronoun draws its reference is called the antecedent. John is the antecedent for himself. John and himself are co-referential. Constraints on co-reference Johni saw himselfi. *Himselfi saw Johni. *Johni’s mother saw himselfi. It is impossible to assign the same referent to John and himself in the second and third sentences. What is different between the good and bad sentences? John’s mother John’s mother is an NP. [John’s mother]i saw herselfi. She saw John. But it’s an NP that is made up of smaller pieces (John’s and mother). So what is the internal structure of the NP John’s mother? [NP John’s mother] Remember that pronouns come in three distinguishable forms (in English): I, he, she Me, him, her My, his, her nominative accusative genitive The genitive case forms seem to have pretty much the same kind of “possessive” meaning that John’s does. So, let’s suppose that John’s is the genitive case form of John. [NP John’s mother] Another point about John’s mother is that it seems that the head should be mother. John’s sort of modifies mother. Sort of like an adjective does… sort of like an adverb does for a verb… Let’s suppose (for now! In chapter 7 we’ll revise this) that John’s is just adjoined to the NP mother. (Hard to draw clearly) NP NP NPi John’s mother Binding What is the difference between the relationship between John and himself in the first case and in the second case? * VP NP NP NPi John’s mother VP NPi John V V saw NPi himself V V see NPi himself Binding We think of the position that John is in in the first tree as being a position from which it “commands” the rest of the tree. It is hierarchically superior in a particular way. Really, “non-inferior” * VP NP NP NPi John’s mother VP NPi John V V saw NPi himself V V see NPi himself Tree relations A B C D E A node X c-commands its sisters and the nodes dominated by its sisters. Tree relations A B C D E A node X c-commands its sisters and the nodes dominated by its sisters. B c-commands C, D, E. Tree relations A B C D E A node X c-commands its sisters and the nodes dominated by its sisters. B c-commands C, D, E. D c-commands E. Tree relations A B C D E A node X c-commands its sisters and the nodes dominated by its sisters. B c-commands C, D, E. D c-commands E. C c-commands B. Binding So, again what is the difference between the relationship between John and himself in the first case and in the second case? * VP NP NP NPi John’s mother VP NPi John V V saw NPi himself V V see NPi himself Binding In the first case, the NP John ccommands the NP himself. But not in the second case. * VP NP NP NPi John’s mother VP NPi John V V saw NPi himself V V see NPi himself Binding When one NP c-commands and is coindexed with another NP, the first is said to bind the other. * VP NP NP NPi John’s mother VP NPi John V V saw NPi himself V V see NPi himself Binding Definition: A binds B iff A c-commands B A is coindexed with B “if and only if” * VP NP NP NPi John’s mother VP NPi John V V saw NPi himself V V see NPi himself Binding Principle A of the Binding Theory (preliminary): An anaphor must be bound. A is for anaphor? That’s good enough for me… * VP NP NP NPi John’s mother VP NPi John V V saw NPi himself V V see NPi himself Principle A This also explains why the following sentences are ungrammatical: *Himselfi saw Johni in the mirror. *Herselfi likes Maryi’s father. *Himselfi likes Mary’s fatheri. There is nothing that c-commands and is coindexed with himself and herself. The anaphors are not bound, which violates Principle A. Binding domains But this is not the end of the story; consider *Johni said that himselfi likes pizza. *Johni said that Mary called himselfi. In these sentences the NP John c-commands and is coindexed with (=binds) himself, satisfying our preliminary version of Principle A—but the sentences are ungrammatical. John didn’t say that anyone likes pizza. John didn’t say that Mary called anyone. Binding domains Johni saw himselfi in the mirror. Johni gave a book to himselfi. *Johni said that himselfi is a genius. *Johni said that Mary dislikes himselfi. What is wrong? John binds himself in every case. What is different? In the ungrammatical cases, himself is in an embedded clause. Binding domains It seems that not only does an anaphor need to be bound, it needs to be bound nearby (or locally). Principle A (revised): An anaphor must be bound in its binding domain. Binding Domain (preliminary): The binding domain of an anaphor is the smallest clause containing it. Pronouns *Johni saw himi in the mirror. Johni said that hei is a genius. Johni said that Mary dislikes himi. Johni saw himj in the mirror. How does the distribution of pronouns differ from the distribution of anaphors? It looks like it is just the opposite. Principle B Principle B A pronoun must be free in its binding domain. Free Not bound *Johni saw himi. Johni’s mother saw himi. B is for bpronoun, that’s good enough for me. Principle C We now know where pronouns and anaphors are allowed. Consider the following. *Stuarti saw himi in the mirror. Stuarti’s mother saw him in the mirror. *Hei saw Stuarti in the mirror. Hisi mother saw Stuarti in the mirror. Principle C What’s going wrong with these sentences? The pronouns are unbound as needed for Principle B. What are the binding relations here? *Hei likes Johni. *Shei said that Maryi fears clowns. Hisi mother likes Johni. Hisi mother said that Johni fears clowns. Principle C Binding is a means of assigning reference. R-expressions have intrinsic reference; they can’t be assigned their reference from somewhere else. R-expressions can’t be bound, at all. Principle C An R-expression must be free. C is for r-eCspression… oh, never mind. Binding Theory Principle A. An anaphor must be bound in its binding domain. Principle B. A pronoun must be free in its binding domain. Principle C. An R-expression must be free. The binding domain for an anaphor is the smallest clause that contains it. Bound: coindexed with a c-commanding antecedent (Free: not bound). Constraints on interpretation Binding Theory is about interpretation. Only a structure that satisfies Binding Theory is interpretable. pronounce Lexicon Merge Workbench interpret Constraints on interpretation If we put together a tree that isn’t interpretable, the process (derivation) is sometimes said to crash. pronounce Lexicon Merge Workbench interpret Constraints on interpretation If we succeed in putting together a tree that is interpretable (satisfying the constraints), we say the process (derivation) converges. pronounce Lexicon Merge Workbench interpret Negative Polarity Items Certain words in English seem to only be available in “negative” contexts. Pat didn’t invite anyone to the party. Pat does not know anything about syntax. Pat hasn’t ever been to London. Pat hasn’t seen Forrest Gump yet. *Pat invited anyone to the party. *Pat knows anything about syntax. *Pat has ever been to London. *Pat has seen Forrest Gump yet. Negative Polarity Items These are called negative polarity items. They include ever, yet, anyone, anything, any N, as well as some idiomatic ones like lift a finger and a red cent. Pat didn’t lift a finger to help. Pat didn’t have a red cent. *Pat lifted a finger to help. *Pat had a red cent. Licensing NPIs are only allowed to appear if there’s a negative in the sentence. John didn’t invite Mary to the party, did he? John didn’t invite anyone to the party. John invited Mary to the party, didn’t he? *John invited anyone to the party. Nobody invited Mary to the party, did they? Nobody invited anyone to the party. Negation gives an NPI “license to appear”: NPIs are licensed by negation in a sentence. Just like you need a driver’s license to drive a car (legally), you need negation to use a NPI (grammatically). Any Just to introduce a complication right away, there is a positive-polarity version of any that has a different meaning, known as the “free choice any” meaning. This meaning is distinguishable (intuitively) from the NPI any meaning, and we are concentrating only on the NPI any meaning—for now, we will just consider any to be ambiguous, like bank. John read anything the professor gave him. Anyone who can understand syntax is a genius. In fact, there are a couple of things other than negation that license NPIs; we’ll ignore them for now. Pick any card. Did anyone bring cake? Negative Polarity Items But it isn’t quite as simple as that. Consider: I didn’t see anyone. *I saw anyone. *Anyone didn’t see me. *Anyone saw me. It seems that simply having negation in the sentence isn’t by itself enough to license the use of an NPI. Negative Polarity Items As a first pass, we might say that negation has to precede the NPI. I didn’t see anyone. Nobody saw anyone. *Anyone didn’t see me. *Anyone saw nobody. But that’s not quite it either. *[The picture of nobody] pleased anyone. Negative Polarity Items *[The picture of nobody] surprised anyone Nothing surprised anyone VP VP NP The picture of nobody V V surprised NPi V nothing V NPi suprised anyone NP anyone Exercise to ponder Young kids (5-6 years) seem to accept sentences like (1) as meaning what (2) means for adults. (1) Mama Bear is pointing to her. (2) Mama Bear is pointing to herself. Suppose that, contrary to appearances, kids do know and obey Principle B. Look carefully at the definitions of Binding Theory. If Principle B isn’t the problem, what do you think kids are getting wrong to allow (1) to have the meaning of (2)? Think in particular about how you decide which index to assign to her. What is the implication of having the same index? What is the implication of having different indices?