Irish Art - Art Teachers' Association of Ireland

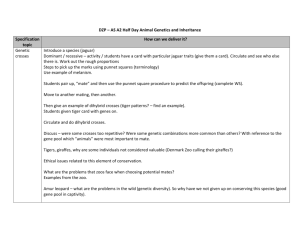

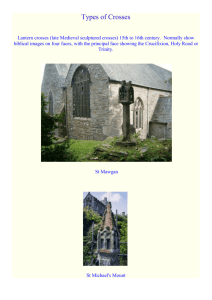

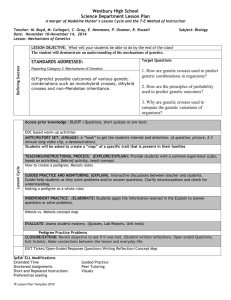

advertisement

Irish Art Early Christian Ireland Intro to Christianity • St. Patrick came to Ireland in 432 A.D. and with him brought Christianity to Ireland. Ogham • • • Although the Romans never invaded Ireland their influences travelled through trade and contact with them. One feature that travelled was writing based on the Roman alphabet known as ‘ogham’. We developed into a civilisation getting the island the title of ‘Saints and Scholars’. The merging of Roman designs onto our brooches, jewellery, manuscripts and the use of precious stones inserted into metal objects. Two phases of Early Christian Irish Art • • • • From 5th to mid 8th century Early monastic settlements. Few objects remain except some brooches and some pins and the first decoration of capital letters in manuscripts i.e. in the Cathach. 8th century huge development of Irish Art with the early stone crosses and the Book of Durrow. • • • • • • From mid 8th to the 9th century. Golden Age of Irish Art. Technical skills reached perfection. Tara Brooch. Book of Kells. Crosses of Monasterboice and Moone. The Church • • • • • St. Patrick and other missionaries established small communities ruled over by their own bishop. This system changed gradually during the 6th and 7th centuries to monastic foundations. The result…..a Church organisation. Recognising the authority of the abbot of the monastery more than the bishop of the diocese. Abbots were usually laymen and the monastery was usually passed down father to son. The monasteries also became places of learning and endless days were often spent on the art of manuscripts. Abbots had high social standing and strong connection with the Secular rulers who lived in ring forts or raths or crannogs. These secular rulers were their patrons to the arts for hundreds of years. Skellig Michael • • • • • • • Skellig Michael, Co. Kerry Monastic settlement perched high on a rocky island 7 miles off the coast of Kerry. Dedicated to St. Michael, the patron saint of high places. Stones steps lead 180m up to a little stone church of St. Michael also surrounded by 6 beehive huts Built with Corbelling technique. The 2 small oratories are built the same but in a rectangular shape. Both have one window and a low doorway. 9th to 11th century???? Gallarus Oratory • • • • • • Dingle Peninsula, Co. Kerry. Between 8th and 12th century. Rectangular church built with the corbelling technique. With this shape it was important to select well-shaped stones which fitted together. Walls slope inwards for strength. Has a low door and one window on the gable wall. Not far from the church is a flat stone Cross Marker. Asking people to pray in memory of someone. Stone with a cross in a circle Round Towers • • • • • Round Tower at Ardmore, Co. Waterford. 10th century started from. Not bell towers but a feature of the monasteries. Probably to mark the status of wealth and sophistication. Stored valuables or places of refuge maybe. Tall, slender and tapering with a cone shaped corbelled cap. Usually four windows facing diff directions at the top with one window for each storey below. The doorway 2 or 3m from the ground reached by ladder and the wooden floors inside. Glendalough tower 31.4m high. Metalwork 8th-12th • • • • • • • During the Christian era, new artistic traditions developed in Ireland fusing Germanic art with traditions from the Roman world and traditions around the Mediterranean. These fused to the La Tene style art. This style was found in manuscript illumination i.e. the Book of Durrow. And so began the link between the style of manuscripts and metalwork of the 7th and 8th centuries. 600 A.D. fine Irish craftsmen changed considerably from the late Iron Age. Solid silver objects had appeared, enamel was used more and the new technique of millefori glass (method of producing motifs by covering a cane of glass with layers of different coloured glass and cutting into short lengths) had been adopted. Now new types of objects were fashionable i.e. large pins for fastening garments and penannular brooches. There were workshops all over the country i.e. monastic site at Armagh and Ballinderry crannog Co. Offaly. Penannular brooch got its name because of the gap in the ring which was developed from a Roman military-style brooch. Motifs in metalwork were also suitable for manuscripts. The colouring in manuscripts was approached in the coloured enamel in metalwork. 8th century shows a huge range of techniques, all over decorations various effects found in other traditions. New techniques such as gold filigree, gilding and silvering, die-stamping and a variety of new colours in glass and enamel were added to the native skills of bronze casting, engraving and colouring with red enamel. Early 8th century era known as the ‘Golden Age’…… time of perfection. Examples the Tara Brooch and the Ardagh Chalice. Ballinderry Brooch • • • • Ballinderry Brooch, Co. Offaly 600A.D. National Museum of Ireland. Millefori glass in the little plate on the terminals, along with sunken areas of red enamel. Decorated with bands of lines, hatching and herringbone design. Full circle of bronze with a pin attached which would fasten through the garment. Rinnagan Crucifixion Plaque • • • • • Rinnagan, Co. Rosscommon. National Museum of Ireland. Late 7th century. Also known as St. John’s crucifixion plaque. Possibly acted as a book cover suggested by several holes surrounding the piece. Made from bronze. Main attention directed to the face of Christ. Nailed feet point downwards, arms outstretched and nailed to the cross. Design combines herringbone pattern, spirals and zigzags. Ornament on the garment is La Tene style. Christ wears a long sleeved garment with interlace at the wrists. Around Christ small angels, the lance bearer and the sponge bearer. They attend to Christ with spiral designs on their wings too. Ardagh Chalice • • • • Ardagh Chalice, National Museum of Ireland Found in 1868 near Ardagh, Co. Limerick by a boy digging potatoes. It was found with four brooches and a bronze chalice. Must have been part of the collection of a rich monastery. Simple design using gold and silver, moulded coloured glass and light engraving. There are large areas free of decoration. But the decoration used elsewhere involves plain interlace and animal interlace, scrolls, plaits and frets in gold wire filigree. Other techniques used are engraving, casting, enamelling and cloisonne, a method of enamelling which separates the colours with thin strips of metal. The three main elements of the chalice are the bowl, stem and broad foot. Ardagh Chalice • • • Complex gold filigree work forms a band around the chalice broken by red and blue glass studs. Under this band, engraved lightly into the silver, are the names of all the apostles except Judas. The bowl of the chalice is joined to the base by a thick bronze stem. Stem is heavily gilded (thin layer of gold impressed on to the metal). Here the decoration is the most intricate and involved of all. The base is formed by a cone-shaped foot around which is a decorated flange for extra stability. This flange has square blocks of the blue glass separated by panels of interlace and geometric ornament. In the centre of the underside of the base is a circular crystal surrounded by gold filigree and green enamels. The outer edge of the flange underside is divided into eight, with six copper studs and two silver. Ardagh Chalice • • The handles on both sides are a concentrated area of rich colours and patterns. Decorated with coloured glass panels in red, blue, green and yellow, in between are tiny panels of complex and skilled gold wire filigree work, coloured glass and a cloisonne enamelled stud in the centre. The gold filigrees of the Ardagh Chalice and the Tara Brooch were apparently derived from Germanic work, reaching new heights of elaboration and minuteness. Tara Brooch • • • • • • • • • • Tara Brooch, National Museum of Ire, 8th century Found near the seashore of Bettystown Co. Meath after the cliff collapsed by a jeweller and named it Tara and it remained. It’s a form of penannular brooch based on a Roman design. No particular Christian connection. Most likely to be made for the personal adornment of a queen or king or bishop. It is tiny and is a ring brooch. And there is no gap which the pin can pass through so it is called a pseudo-brooch chains and loops are needed for fastening a chain like this. The point where the chain joins the brooch is beautifully decorated: two glass studs in the form of human heads. Made of bronze, back covered in copper and glass studs, front with gold, amber and glass. Gold is worked into filigree panels, some of which have fallen off. Decorated with spirals, loops, animal and bird heads. Back of brooch is also highly decorated. There are two plates. La Tene style is dark against a silver background. Chain is attached to the brooch by two animal heads at each end of a little plate. Two human heads lie in the centre of this plate. These human faces are purple. Straight pin with triangular head with gold filigree, amber and glass. Cast and gilded kerbschnitt ornament appears on the shaft and head of the pin. Occurs also on the inner and outer edges of the ring. Kerbschnitt is a method of casting which imitates wood carving. Derrynaflan Hoard • • • National Museum of Ire, mid 8th century. Found at an ancient monastery of Derrynaflan, Co. Tipperary in recent years. The hoard contained a chalice very similar to the Ardagh Chalice. Suggesting this may have been a common design to the Irish Church. The hoard also contained a silver paten and a beautiful strainer-ladle The paten contains such techniques as filigree, enamelling, casting, stamping of thin gold and knitting of wire mesh. Metalwork 11th and 12th century • • • • • • • Cross of Cong, early 12th century Artistic production declined during the 9th and 10th century but continued in the production of stone crosses. The 11th and 12th century was a period of peace between the Vikings and the coming of the Normans, stoneworkers and metalworkers produced works of art equally. Almost all metalwork was produced for the church consisting mainly of highly ornamented shrines and reliquaries connected with Irish saints. Shrines like the Cross of Cong and the Shine of St Patrick’s Bell were made to hold objects or relics associated with the saints such as books or bells. While objects like the Shrine of St Lachtin’s arm may have been to hold bones of a saint. Processional cross, in the centre a crystal rock set in the silver mount and surrounded by gold filigree. Tubular silver edging surrounds the gently curved outline of the cross punctuated by bossed rivets. Cross surface divided into sections of cast bronze thread-like snakes holding animal shapes. The staff and cross are linked by animal jaws biting the base of the cross. animals have scaled heads, pointed ribbed snouts, little curved ears and blue glass eyes. Below these heads is an ornate knob similar to that found on croziers. Metalwork 11th and 12th century • • • • • • • • • Shrine of St Patrick’s Bell (first picture) Clonmacnoise crozier (second picture) Great care was taken creating these objects. In the Irish Christian Church, croziers were held in great reverence. It is one of the finest in Europe of this time. One notable feature of the metalwork is the blend of Scandinavian influences, seen through the use of animal imagery, with native Irish work. Craftsmanship shows high patronage by the rich and well-todo clans and royalty. Shrine of St Patrick’s Bell, early 12th century. Has a tapering body and curved top. Front covered with a gilt silver frame in which there were originally 30 gold filigree panels. Variety of intertwined single or animal pairs forming regular figure eight shapes. Large rock crystal occupies the centre space. On the back, series of interlocking crosses pierced into a silver frame against a bronze background. Sides are decorated with panels of animal interlace separated by a circular cross. Rings at sides suggest it was meant to be carried. Clonmacnoise crozier, early 12th century Formed by two tubes of bronze wrapped around a wooden staff finished with a curved crook. Crook is hollow with animal interlace in silver, edged with niello inlay down the sides. Front of crook, grotesque bearded human head with staring eyes. Behind this a crest running down the curve of the crook. The crest formed by a series of dog-like animals. Base of the crook, front and back formed with grotesque animal heads. Under the base, two pairs of cat-like animals standing with arched backs and legs entertwined and twisted tails. Carved stone crosses • • • Dunvillaun slab, Co. Mayo, 6th to 12th century. Early Christian Ireland there was no great tradition of building or carving in stone. Standing stones were a feature of pre-Christian Ire and the tradition continued into the first Christian symbols of the cross. The shape of the stone never changed maybe because of the old irish belief if interfering with the spirit of the stone. In this particular stone and common to others we find a Greek cross on the reverse face of the slab and rare early representation of the crucifixion is engraved in the front. Carved stone crosses • • • Reask pillar Co. Kerry, 6th to 12th century. Maltese cross supported by lines and spirals of Celtic decoration and imagery in the form of a Greek cross. Large numbers of engraved grave slabs survive near important monasteries like Clonmacnoise. Carved stone crosses • • • • Cardonagh cross, Donegal, 7th century First free standing cross. Idea of the Christian cross inscribed on a pillar goes further and the cross itself is cut out of the stone. Decorated all over with broad ribbon interlace edged with a double line similar to that found in the Book of Durrow. On one side this is combined with figures. This is the first cross to but cut in a cruciform shape. High Crosses • • Most Irish High Crosses have the distinctive shape of the ringed Celtic Cross, and they are generally larger and more massive, and feature more figural decoration, than those elsewhere. They have probably more often survived as well; most recorded crosses in Britain were destroyed or damaged by iconoclasm after the Reformation. The ring initially served to strengthen the head and the arms of the High Cross, but it soon became a decorative feature as well. The High Crosses were status symbols, either for a monastery or for a sponsor or patron, Preaching crosses, and may have had other functions. The early 8th century crosses had only geometric motifs, but from the 9th and 10th century, biblical scenes were carved on the crosses. There were no crosses made after the 12th century, until the Celtic Revival, when similar crosses began to be erected in various contexts. Muirdeach High Cross • • • • Muiredach's High Cross is a high cross from the 10th or possibly 9th century, located at the ruined monastic site of Monasterboice, County Louth, Republic of Ireland Muiredach's High Cross is one of three surviving high crosses located at Monasterboice These crosses are all made of sandstone and are referred to as the North, West, and South Crosses. It is not certain whether they stand in their original locations. The South Cross is commonly known as Muiredach's cross because of an inscription on the bottom of the west-face. The cross measures about 19 feet (5.8 m) high; including the base, which measures 2 feet 3 inches (0.69 m). The cross is made of sandstone which is yellow in colour. The main shaft of the cross is carved from a single block of sandstone; the base and the capstone on the top are carved from separate stones. The base is the shape of a truncated pyramid of four sides. It measures 2 feet 2 inches (0.66 m) high and 4 feet 9 inches (1.45 m) at the bottom Muiredeach High Cross • • Every piece of the cross is dived into panels which are decorated with carvings. The carvings are remarkably well preserved, however, they certainly would have originally had much finer detail. Even so, certain details about clothing, weapons, and other things, can still be clearly made out. Biblical themes dominate the carved panels; though there are pieces which feature certain geometric shapes and interlace ornaments.[4] All, except one, of the figures is depicted bareheaded. The lone figure with headgear is Goliath, who wears a conical helmet.[7] Generally the hair is worn clipped in a straight line over the forehead, though in some cases it is shown to be distinctly curly. Many of the figures have no facial hair, though several of them wear very long moustaches, with heavy ends which hang down to the level of the chin. There are very few beards represented; those shown with beards are Adam, Cain, Moses and Saul.[8] Macalister considered that the artist excelled in the geometric and abstract patterns which appear on the cross. On the ring surrounding the head of the cross, there are 17 different patterns. Macalister stated that Celtic geometric patterns fall into three categories: spiral, interlace, and key-patterns. East Face of Muiredach • • • Central Panel across the middle:This panel represents The Last Judgement. It contains more than 45 figures; in the centre, Jesus is standing, holding a floriated sceptre in the right hand and the Cross of the Resurrection in the left. On the head of Christ there is a bird—possibly a phoenix, the symbol of the Resurrection. At the foot of Christ is a small, kneeling figure with an open book over the head.[13] Macalister considered that this likely represents an angel with the Book of Life.[14] On the right of Christ is David enthroned, playing a harp, upon which the Holy Spirit rests in the form of a dove; behind are a choir of angels playing instruments. On the left of Christ are the Lost Souls, being driven away from Christ by a devilish creature holding a trident.[13] First under the arm of the ring:This panel represents the Adoration of the Magi. Usually the Magi are represented as three, because of their three gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. However, in some cases, likely for symmetry's sake, they are also depicted in a group of four—as in this panel. Over the head of Christ is the Star of Bethlehem.[17] Second last panel:This panel depicts the battle between David and Goliath. The two combatants stand in the middle of the panel are likely meant to be in the foreground; there is figure on either side of the combatants which are likely meant to be seen as in the background. David has a shepherd's crook over one shoulder, and in the other hand he holds a sling, hanging open to show that the stone has already been cast. Over his shoulder is suspended a wallet in which the stones were stored. Goliath is depicted on his knees, with a hand against his forehead, to indicate that he has been struck there. He wears a conical helmet; being the only one character depicted on the cross to wear any kind of head-covering. He bears a round shield and a short dagger. To the left of the two combatants is a seated figure, likely King Saul, who also has a round shield and carries a short sword, and is drinking from a horn. The fourth figure, to the right of the combatants, is according to Macalister, likely Jonathan, though this figure may also represent Goliath's armourer West face of Muiredach • • Central Panel of ring:This panel depicts the Crucifixion of Christ. The central figure is Christ upon the cross. He is fully clothed, which is normal in European representations of the Crucifixion at this date. His arms are stretched straight and horizontal. The lance-bearer and spongebearer are placed symmetrically on either side of Christ. Macalister thought that the two circular knobs appearing between them and Christ propably represent the sun and moon, referring to the darkness at the Crucifixion. Macalister stated that it was uncertain what the bird at the foot of the cross represented. He stated that some thought it is a symbol of the resurrection, and that others thought it represents the dove of peace. There is a similar bird above the Crucifixion on the high cross at Kells. On the outside of the lance-bearer and sponge-bearer are two small figures—a woman, and a man kneeling on one knee, probably representing the Virgin Mary and John. Last panel:his panel shows three men; it is thought to represent the seizure of Christ in the garden of Gethsemane. The panel shows Christ, in the middle, holding a staff and being arrested by two men with military equipment. A similar representation of this scene occurs in the Book of Kells, and is also pictured on the Cross of King Flann at Clonmacnois.[27] Ahenny High Cross • • • Location: In Ahenny, County Tipperary, near the Kilkenny border. Dimensions: North cross 3.65 meters tall. South cross 3.35 meters tall Features: The two sandstone Ahenny crosses are impressive and both date from the 8th to 9th century, among the earliest of the ringed high crosses. These crosses reproduce in stone what would have been patterns in earlier wooden crosses, complete with patterns that mimic the metalwork that held the wooden cross together. While later high crosses concentrated on biblical scenes, these earlier crosses carried intricate interlace designs on almost every surface. Only the bases carry any panels with figure carving which is considerably worn and difficult to make out. Many interpretations of these carvings have been proposed. The north cross base is said to carry scenes of (north) a procession with a chariot, (south) a funeral procession with a cleric holding a processional cross followed by a horse bearing a headless body which is being attacked by ravens and a man carrying the head which is seen full face, (east) Adam naming the animals and (west) the mission of the apostles and/or the Seven Bishops (apparently a local tradition). The base of the south cross is worn beyond most recognition. It is said to depict (north) hunting scenes, (east on the left) Daniel in the Lion's Den and (south on left) The Fall of Man. Another odd feature of these crosses are the removable cap stones known as miters (bishop's hats). High Cross of Moone • In Moone, Co Kildare stands the second tallest high cross in Ireland. The shape of which is quite unique, and consists of three parts, the upper part and base were discovered in the graveyard of the abbey in 1835 and re-erected as a complete cross, but in 1893 the middle section of the shaft was discovered and the cross was finally reconstructed to its original size, now standing at 17.5 feet the cross has been erected inside the ruins of the medieval church. The theme of the cross is the help of God, how God came to their assistance in their hour of need, Daniel in the lions pit, the three children in the fiery furnace and the miracle of the loaves and fishes amongst the scenes depicted. The monastery is believed to have been founded by St Palladius in the 5th century and dedicated to St Columcille in the 6th century, and the cross constructed from granite during the 8th Century. Cross of Moone details: The 12 Apostles are carved on the base of the west side, below the crucifixion. The Temptation of St Anthony and a six-headed beast on the North base. Cross of Moone details: East face showing Daniel in the Lions pit and the sacrifice of Isaac. South side, the miracle of the loaves and fishes, the flight into Egypt. Irish Illuminated Manuscripts Book of Durrow Book of Durrow • • • • The Book of Durrow (Dublin, Trinity College Library, MS A. 4. 15. (57)) is a 7th-century It is possibly the oldest extant complete illuminated gospel from Ireland. The text includes the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, plus several pieces of prefatory matter It contains a large illumination program including six extant carpet pages, a full page miniature of the four evangelist's symbols, four full page miniatures, each containing a single evangelist symbol, and six pages with decorated text. Each Gospel begins with an Evangelist's symbol - a man for Matthew, an eagle for Mark (not the lion traditionally used), a calf for Luke and a lion for John (not the eagle traditionally used). Each evangelist symbol, except the Man of Matthew is followed by a carpet page, followed by the initial page. Book of Durrow • • The first letter of the text is enlarged and decorated, with the following letters surrounded by dots. Parallels with metalwork can be noted in the rectangular body of St Matthew, which looks like a millefiori decoration, and in details of the carpet pages. There is a sense of space in the design of all the pages of the Book of Durrow. Open vellum balances intensely decorated areas. Animal interlace of very high quality appears on folio 192v. Other motifs include spirals, triskeles, ribbon plaits and circular knots in the carpet pages and borders around the Evangelists