A Behavioural Approach to Language Assessment and Intervention

advertisement

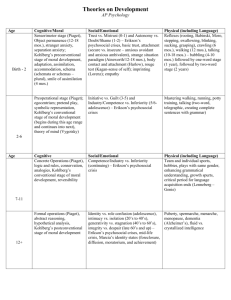

Skinner’s Analysis of Motivation: Ten Applications for Improving Autism Treatment Mark L. Sundberg, Ph.D., BCBA-D (www.marksundberg.com) Motivation • • • • • • • Motivation is a major topic in psychology, especially applied psychology A Google search of “motivation” produced 257 million hits 42 million for “reinforcement” 7 million for “stimulus control” 97,000 for discriminative stimulus (SD) Behaviorists are rarely credited for any positive contribution to the study of motivation In fact, discussions of behavioral approaches to motivation are usually misguided and pejorative (e.g., Dan Pink’s TED presentation, SonRise vs. ABA) A Behavioral Analysis of Motivation • • • • • An often missed element of Skinnerian psychology is that motivational control is an antecedent variable that is different from stimulus control and reinforcement (Skinner, 1938, 1953, 1957) In Behavior of Organisms (Skinner, 1938) Skinner devoted two full chapters to motivation; Chapter 9 titled “Drive” and Chapter 10 titled “Drive and Conditioning: The Interaction of Two Variables” Science and Human Behavior (1953) had three chapters on motivation Keller and Schoenfeld (1950) stated, “A drive [motivation] is not a stimulus…a drive has neither the status, nor the functions, nor the place in a reflex [behavior] that a stimulus has…it is not, in itself either eliciting, reinforcing, or discriminative” (p. 276) Keller and Schoenfeld suggested the term “establishing operation” be used for “drive” to distinguish it from the various types of stimuli A Behavioral Analysis of Motivation • • • • • The study of motivation was not carried through to Applied Behavior Analysis in the 1960s, 70s, & 80s Michael (1993) pointed out, “In applied behavior analysis the concept of reinforcement seems to have taken over much of the subject matter that was once considered a part of the topic of motivation” (p. 191) Applied research on motivation is virtually nonexistent in the first 20 years of the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis (JABA) The Journal contained no entries for “establishing operations” or “motivation” in the first cumulative index (1968-1978) During the next 10 years (1979-1988) there were still no entries for “establishing operation.” However, there were 5 entries for “motivation,” but they all involved motivation as a consequence, rather than as an antecedent variable A Behavioral Analysis of Motivation • • • In addition, the experimental analysis of motivation is mostly absent from the 57 years of research in the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior (JEAB) Michael (1993) noted that “the basic notion [MO] plays only a small role in the approach currently identified as behavior analysis” (p. 191) But most importantly, the neglect of motivation “leaves a gap in our understanding of operant functional relations” (Michael, 1993, p. 191) A Behavioral Analysis of Motivation • • Skinner discussed the topic of motivation in every chapter of the book Verbal Behavior (1957), usually with his preferred terminology of “deprivation, satiation, and aversive stimulation” “Thirty points about motivation from Skinner’s book Verbal Behavior” (Sundberg, 2013) Thirty Points About Motivation from Skinner’s Book Verbal Behavior (Sundberg, 2013) A Behavioral Analysis of Motivation • • • • Skinner discussed the topic of motivation in every chapter of the book Verbal Behavior (1957), usually with his preferred terminology of “deprivation, satiation, and aversive stimulation” “Thirty points about motivation from Skinner’s book Verbal Behavior” (Sundberg, 2013) Jack Michael and colleagues have published various refinements and extensions of Skinner’s analysis (Laraway, Snycerski, Michael, & Poling, 2003; Michael, 1982, 1988, 1993, 2000, 2004, 2007) “Discriminative variables (SDs) are related to the differential availability of an effective form of reinforcement given a particular type of behavior; motivative variables are related to the differential reinforcing effectiveness of environmental events’’ (Michael, 1993 p. 193) (see also Michael, 1982) Establishing Operations (Michael, 1993) A Behavioral Analysis of Motivation • • • • • • • • • • Motivation, in lay terms, is often talked about as wanting or needing things or events For example, food deprivation There are two behavioral effects involved 1) the value of food becomes stronger 2) food seeking behaviors are evoked Or, being highly motivated to search the internet for Club Penguin Two behavioral effects 1) the value of a computer and a website address becomes stronger 2) web searching behaviors are evoked When values are low (satiation, or website found) behavior is abated A Behavioral Analysis of Motivation: Michael’s (2007) Framework • • • • • An increase in the value of food or a website url is termed an establishing operation (EO) while a decrease in the value is termed an abolishing operation (AO) The term motivating operations (MOs) is an omnibus term for these value changing effects (EOs and AOs) The value changes then in turn affect behavior (value-altering effect) EOs evoke specific behaviors, AOs abate specific behaviors (behavior-altering effect) Michael’s definition of motivation: “any environmental variable that (a) alters the effectiveness of some stimulus, object, or event as a reinforcer and (b) alters the current frequency of all behavior that has been reinforced by that stimulus, object, or event” (2007, p. 375) Michael’s Chapter on Motivating Operations in Cooper et al. (2007) A Behavioral Analysis of Motivation: Summary • • • • MOs constitute a separate basic principle of behavior MOs are antecedent events, not consequences All types of MOs are separate from stimulus control MOs and SDs frequently occur together as forms of “multiple control” The Basic Principles of Operant Behavior Stimulus Control (SD) Motivating Operation (MO) Response Reinforcement Punishment Extinction Conditioned reinforcement Conditioned punishment Intermittent reinforcement A Behavioral Analysis of Motivation: Summary • • • • • • • • • • All types of MOs are separate from, but related to, reinforcement MOs effects are separate from schedules of reinforcement effects Aversive stimulation can function as MOs Aversive stimulation as an antecedent (an MO) is different from aversive stimulation as a consequence (punishment) Escape and avoidance are MO effects, not SD effects MOs may involve unconditioned or conditioned variables A single MO can control large repertoires (e.g., revenge) MOs are typically private events Collateral behavior can help to determine MO level (e.g., reaching) Much of what is termed “emotion” involves MOs (S&HB, chap. 10) The Application of Establishing Operations (Sundberg, 1993) Application 1: MOs as Antecedents Provide an Additional Tool for Assessment and Intervention • • • • • • • • • MOs play a significant role in multiple facets of the assessment and intervention process for children with autism MOs can be manipulated as an independent variable (like reinforcement, SDs, schedules, etc.) MOs in relation to language acquisition and academics (e.g., math) MOs in relation to social behavior (e.g., peer interaction) MOs in relation to problem behaviors (e.g., aggression) MOs in relation to learning barriers (e.g., scrolling in manding) MOs in relation to group skills (e.g., aversive events evoke escape) MOs in relation to self-help skills (e.g., clean hands) MOs in relation to nonverbal skills (e.g., fine motor) Application 2: MOs as the Primary Antecedents for Manding • • • • • • • • All mands are controlled by motivating operations (MOs) There must be an MO at strength to conduct mand training MOs vary in strength across time, and the effects may be temporary MOs must be either captured or created to conduct mand training MOs may have an instant or gradual onset or offset Instructors must be able to reduce existing negative behavior controlled by MOs Instructors must be able to identify the presence and strength of MOs, and capitalize upon them for teaching opportunities Instructors must know how to bring verbal behavior under the control of MOs Application 3: Demand can Weaken a Motivating Operation (MO) • • • • • There is a direct relation between the value (MO) of a reinforcer and how much work (response effort) is required to obtain that reinforcement (e.g., Alling & Poling, 1994) Too much of a work demand can reduce the strength of an MO An iPad may be reinforcing if it is noncontingent, but less so if work is required Don’t be dependent on rfmt. surveys and preference assessments Sitting, attending, and responding to task demands can be quite a high response requirement for some children (video: Julian) Application 3: Demand can Weaken a Motivating Operation (MO) • • • • • • • There is a direct relation between the value (MO) of a reinforcer and how much work (response effort) is required to obtain that reinforcement (e.g., Alling & Poling, 1994) Too much of a work demand can reduce the strength of an MO An iPad may be reinforcing if it is noncontingent, but less so if work is required Don’t be dependent on rfmt. surveys and preference assessments Sitting, attending, and responding to task demands can be quite a high response requirement for some children (video: Julian) Staff must anticipate and account for MO value changes Many intervention strategies are available, for example: • • • identify the conditions under which a change is observed start with a low response requirement and high MO value gradually increase the response requirement Application 4: Aversive MOs as Antecedents • Learned aversive motivators are ubiquitous in everyday behavior • We all encounter bad/undesirable things and events we don’t want • Aversive stimuli increase the value of their termination and evoke behaviors that terminate the stimuli through negative reinforcement • Michael terms these “conditioned motivating operations reflexive” (CMO-R) CMO-R Demand Increased value of termination Student wants to get away Evokes escapeavoidance behavior Tantrum, push materials to floor Remove aversive “negative rfmt.” Task delayed or removed “negative rfmt.” Application 4: Aversive MOs as Antecedents • • • • • • • Adults, tasks, settings, demand, tone of voice, body movements, contexts, materials, problems, etc. can function as aversive MOs Possible CEO-R presence in DTT Teaching children how to handle or remove aversives appropriately Do not let the negative behavior delay or remove the aversive stimulus Do a curriculum analysis, mitigate the aversive, decrease the response effort Increase the reinforcement for responding when aversive MO is present Do not offer reinforcers following negative behaviors (“remember what you’re working for”) Application 4: Aversive MOs as Antecedents Application 5: MOs can Compete With Each Other, and Block or Distort Stimulus Control • • • • • • • • One MO can be more powerful than another MO (e.g., a stim. toy vs. social approval) MOs are sometimes so powerful they overpower SDs (blocking) (e.g., iPad, string, “He does not listen to me”) MOs can distort SDs (e.g., lying, exaggeration) (Brian Williams) Be aware of a student’s strong MOs and possible effects on him Be aware that table-top teaching may not adequately reflect an environment where there are competing MOs Systematically require SD responding when the competing EO is present (may be easiest to start with a relatively weak EO) Be aware that NET may inadvertently cater to powerful MOs Control MOs, don’t let them control you Application 6: Using MOs to help Establish Other Skills (Multiple control) • • • • • • We often learn new skills because of some MO to do so (e.g., new Lego set, new game, navigation system) Incorporating MOs along with SDs and reinforcement can enhance skill acquisition (e.g., Carroll & Hesse, 1987) Learning to tact things a student is interested in Learning intraverbals about favorite topics Reading and writing about favorite topics MOs can help establish nonverbal skills as well (e.g., fine and gross motor skills, grooming skills) Application 7: Breaking Free from MO Control by Using Generalized Conditioned Reinforcement • • • • • MO control can get to be too strong (e.g., iPad, dinosaurs, OCD) “generalized reinforcement destroys the possibility of control via specific deprivations.” (Skinner, 1957, p. 212) “we weaken the relation to any specific deprivation or aversive stimulation and set up a unique relation to a discriminative stimulus. We do this by reinforcing the response as consistently as possible in the presence of one stimulus with many different reinforcers or with a generalized reinforcer. The resulting control is through the stimulus.” (Skinner, 1957, p. 84) Moving a mand to a tact or intraverbal through generalized reinforcement Also, use pictures, satiation, and competing MOs, low demand Application 8: Developing or Repairing Social Skills • • • • • • Weak EOs for social interaction are a problem for many with autism (e.g., may not attend to peers or their interests) Negative behaviors may occur as barriers (e.g., excessive manding, irrelevant IVs, verbal perseveration, weak listener repertoires) There are many complicated behavioral repertoires that fall under the rubric of “social behavior” Create MOs for verbal behavior with peers (e.g., manding to peers) Create MOs for nonverbal behavior with peers (e.g., games, activities) Identify and amelioriate problematic CEO-Rs (e.g., avoiding peers) Application 9: Developing or Repairing Self-help Skills • • • • • • • • • • Distinction between structural and functional self-help skills Why do you brush your teeth, shower, or carefully select clothing? The MOs that control your behaviors may have little effect on teenagers with autism MOs related to avoiding the social punishment of having body odor or bad breath MOs related to positive social reinforcement for a stylish look Creating MOs and assuring that target behaviors are under MO control rather than solely under the control of SDs Set up a play-date, meeting, event, contest, game, etc. Establish and link MOs to a self-checklist Use MOs to identify potential vocational directions Use MOs to teach community living skills Application 10: Asking QuestionsMands for Information • • • • • • • Asking a question is usually a mand, thus the source of control must be an MO The MO for information (verbal or nonverbal) must be the primary source of control (MOask AOdon’t ask) The consequence must be the information, not edibles, tokens, etc. Questions are not developmentally appropriate until approximately a two-year linguistic level Must create or capture an EO (e.g., missing toy) Use prompts (e.g., echoic, textual), fade prompts (e.g., Where’s Elmo) Reinforcement for asking questions must be the information that corresponds with the EO (location of the toy) Conclusions • • • • Motivation is an extremely important aspect of human behavior Behavior analysis has a powerful formulation of motivation that has not been developed much in ABA There is a tremendous need for empirical research on the application of the MO to work with children with autism The applications to the treatment of children with autism are abundant, but it is up to us to develop them THANK YOU! www.AVBPress.com