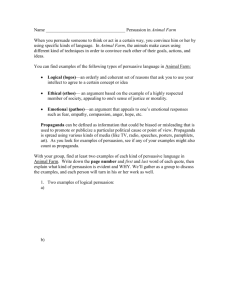

Persuasion

advertisement

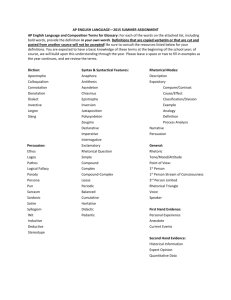

Introduction: In this unit we will be looking at how English is used as an instrument of persuasion, not only in public areas, but also in private sphere of people’s relationships and interactions with one another. The way it is seen in this unit as a means of making decisions, or getting other people to agree with us and do the things we want them to do. Persuasion is everywhere in human communication. It happens at every stage of life, and in every kind of encounter, from the most intimate to the most public. Just as with any other language, persuasion is a major part of what we do with English. Understanding persuasion is therefore an essential part of your exploration of the worlds of English; it permeates all the uses of English, whether old or new, formal or informal, juvenile or adult. We find it every time we speak to others, switch on a TV, or read a newspaper or book. Main learning points include: The idea that convincing other people to think and act as we want them to is one of the main uses of language. Links between the art of rhetoric and the development of democracy in Ancient Greece. The range of attitudes towards the ways that persuasive techniques are used, especially for commercial and political purposes. The continuum between forms of persuasive language used in the public sphere and those used in personal relationships. The question of what makes a good, valid argument in different historical, cultural and institutional context. Persuasion begins very early in life, well before the point when infant behaviour starts to diverge into different cultures and languages. A baby’s first sounds are instinctive, expressing inner states involuntarily: hunger, discomfort, tiredness or fear. The baby begins to seek attention deliberately. She or he cries in order to be fed, entertained or reassured. She or he uses signals artificially, to manipulate, to control, to persuade. At this early stage, it is not language but sound and body movement which are used to persuade. When the infant starts to speak, however, these channels of communication are not replaced by language. They work alongside it, and for this reason are known in linguistics as paralanguage. Paralanguage figures in persuasion throughout life. Adults can still use tears, smiles and raised voices to get their way, and such behaviour is more important than what they actually say. Saying Nice to see you in a morose way is likely to be less convincing than using body language which communicates an overall feeling of connection and warmth. This chapter concentrates on the language of persuasion rather than the paralanguage. Closer to our own time and concerns, think of the extensive use of music and images in advertising. In such examples, language may seem to play only a partial role. Nevertheless, it is through language that persuasion takes on its most complex forms. Persuasion, then, is of great academic interest in the study of any language as it is one of language’s major uses. It is also of great personal concern to all of us. This chapter explores different forms, purposes and effects of persuasion through consideration of examples from a variety of contexts and media. We deal first with examples of persuasion in the public sphere, and from there move on to its use in more personal encounters. In a final section we look briefly at how persuasive language can be evaluated. In figure 6.2 (p. 228), you might think that the demonstrators are trying to persuade the Myanmar government, but in this case, why are they using English rather than Burmese? It seems more likely that they want to influence world opinion to bring pressure on the Myanmar government, and for this purpose, English has more chance of carrying their message effectively around the world. Their verbal messages are accompanied by paralanguage, including raised fists and voices. Classical Rhetoric: The importance of persuasion is that its study has a very long history, predating modern linguistics and discourse analysis by many centuries. In Europe, enquiry into rhetoric (the art of persuasion) dates back at least to the fourth century BC, and was pursued first in Ancient Greece and then in Ancient Rome. There are also traditions from outside Europe, such as Indian rhetoric, dating from the fifth century BC, and Buddhist debating, formalised by the sixth century AD, but in this chapter we will focus on Graeco-Roman ideas. The early studies of rhetoric had the very practical purpose of teaching people how to construct and execute a convincing and effective case, and they arose in two institutional contexts which are still with us today: adversarial law and political campaigning. The most systematic and influential early formulation of the principals of rhetoric was Aristotle’s composed during the 4th century BC, probably in Athens. Some scholars, such as Vickers (1998), have argued that it is no coincidence that an interest in rhetoric emerged in Athens at the same time as democracy. In this political system, where decisions were taken through votes in the Athenian marketplace, it was necessary for the proponents of a policy to win over their fellow citizens. Rhetoric and democracy are perhaps necessarily linked. Ancient rhetorical theory and practice was much preoccupied with categorising rhetorical types, purposes and devices. Over the last two and a half thousand years, the techniques of persuasion have remained essentially the same. Contrasting persuasive strategies: We can gain insight into contrasting persuasive techniques by considering two famous speeches from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. Although this play was written over 400 years ago about events 1500 years earlier, its central event dramatises two approaches to persuasion still highly relevant today. (mentioned pages 230-231). Activity 6.2: These two speeches by Brutus and Antony encapsulate two opposite approaches to persuasion and two ways of relating to an audience. How would you summarise the key differences between them? Can you think of any modern examples of these approaches? One strategy is to set out the evidence and the reasons for holding a point of view, but let the audience decide. It implies an optimistic, respectful view of public opinion. The other strategy is an appeal to emotion and self-interest, clouding the listeners’ judgment and reason. This second strategy implies a lack of respect and low opinion of the audience, but it can be presented by its proponents as realistic and necessary. In the modern media, newspapers provide good examples of both approaches to rhetoric. Rhetorical styles and strategies: These contrasting approaches reflect categorisations of rhetoric which were widely accepted in both Caesar’s and Shakespeare’s time. Aristotle distinguishes three strategies of persuasion: a. reasoned proof (logos) b. emotional appeal (pathos) c. appeal to the good reputation of the speaker (ethos). Logos, pathos and ethos are still the basis of prevalent types of persuasion today. Thus, modern science aspires to carry a point by logos alone. Many charity advertisements use pathos when exhorting people to give money. Other useful categories formulated in ancient rhetoric concern the style of persuasion. Is its use of language grand, or plain, or somewhere in between? Does it seek to overwhelm its hearers, or to be sparse and economical, or to create a perfect balance between the two? And what are its purposes: to judge past events (as in law), to determine the course of future events (as in politics), or for ceremony (as in wedding speech)? Within classical rhetoric, a good deal of attention was paid to rhetorical figures and devices which could be used by the successful speaker. One of these-the so-called (1) rhetorical questionsimulates dialogue by taking an interrogative form, but does not expect a response, either because the answer is too obvious or because the speaker proceeds to answer the question him or herself. You ask, what is our aim? I can answer that in one word: victory. (2)Repetition is also an obvious, well-known and apparently effective rhetorical figure. King Luther uses a device known as a rhetorical triplet, using the phrases ‘This is the faith’ repeated 3 times. That is to say, they repeat the same construction with different words. Try to answer the following questions: Listen to a politician talking or making a speech on radio, television, or You Tube. What rhetorical features do you notice? To what extent are they appealing to reason (logos), or to emotions (pathos) or using the prestige of their position or reputation to reinforce their arguments (ethos)? Can you categorise their rhetorical style as being either (grand) or (plain), or does it lie somewhere in between? Notice: in clip 13.2 and clip 13.3 Kennedy’s rhetorical style leans more towards what the Greek called the (grand) style and Obama’s speech leans more towards the (plain) style. Attitudes towards rhetoric: An underlying assumption in Greek and Roman rhetorical theory was that the art of rhetoric can and should be taught. Rhetoric was seen as a virtuous activity for the public good. In many places this educational tradition continues-USA- where public speaking is taught and examined in high schools, and promoted by numerous organisations and publications as well. Like rhetoric itself, the view of professional persuasion also dates back to classical times. According to Plato, Socrates equated all rhetoric with deceit, arguing that honest speakers should do no more than simply state their evidence and reasons, and then let the audience decide on that basis. If justified, this distrust of professional has important implications. In our time, one reason for a negative view of professional efforts to persuade is the discredited political propaganda associated with totalitarian regimes in the mid-twentieth century, particularly Nazi Germany and the Stalinist USSR. The negative associations of propaganda means that those professionally engaged in persuasion no longer wish to have their activities equated with it. Contemporary attempts to influence opinion –such as advertising, public relations PR and election campaigning- are seen as quite different. We have two distinct views of contemporary persuasion and its relation to totalitarian propaganda. One would see the two as quite separate, and indeed claim that operations such as advertising and PR are an important component of market-oriented economics and liberal democracies promote choice between alternatives and allow healthy competition. Proponents of this view would point to the multiplicity of views current in democracies, and use of similar techniques both by ruling interests and by campaigners against them, including non-governmental organisation (NGOs) such as Greenpeace. They would also insist on distinguishing between arguments which aim to persuade, and those which set out to distort facts, as malign propaganda does. The opposite view would see contemporary persuasion as essentially similar in kind to classic propaganda, as it uses subtler and more effective techniques. Such critics point to the disproportionate funds and resources available to politicians and corporations. For example, the philosopher Habermas suggests that public relations and propaganda are equally manipulative and oppressive, and quite antithetical to genuine democratic decision making. Advertising: As we have seen in the example of Luther King, political rhetoric is prone to repetition at the micro level of words, phrases and grammatical constructions within the same speech. There is also the phenomenon of wholesale repetition, where an entire message is repeated many times. Propaganda relies heavily on such wholesale repetition, as a kind of substitute for reasoned argument. This is part of a general elevation of emotion over evidence, making propaganda very much argument by pathos rather than logos. In addition to this wholesale repetition, advertisements also employ a range of rhetorical devices to attract attention and make the message memorable. Activity 6.4 Pick out two advertisements that catch your attention. What devices do they use to do so? Why do you think they are effective? For example, one memorable advertisement from the 1980s was unusual in that it had no words at all, not even the name of the product. This is a good example of a visual pun, where the image itself calls up the name of the product, Silk Cut Cigarettes. Advertisements, like propaganda, rely heavily on emotion expressing and influencing the values of the society in which they occur. Many of the devices and uses of language taught in classical rhetoric, and still occurring in political oratory today, have also been deployed in political propaganda campaigns and are the stock-in-trade too of contemporary advertising. Thus, advertisers are inordinalitely fond, not only of repetition, whether wholesale or internal but also of figures of speech such as hyperbole, punning, paradox, irony, metaphor and metonymy. Public relations: Advertising can be seen as a branch of a more general phenomenon of persuasive self-presentation, public relations (PR), in which organisations of all kinds seek to portray themselves in a favourable way, both to outsiders (customers) and to insiders (their own employees). Recent decades have witnessed an exponential growth in PR. It has its own theory, a burgeoning workforce, a growing literature, thriving academic courses. Indeed, it is hard to find people or organisations engaged in public life who are not also engaged in PR. This very ubiquity makes PR extremely hard to define and therefore vague. Moloney regards PR as: ‘mostly a category of persuasive …… communications done by interests in the political economy to advance themselves materially and ideologically through markets and public policy-making.’ Moloney also lists discourse features which are typical of PR. Sources, purposes are often undeclared, and therefore unclear. Points are asserted rather than argued or supported by evidence. Information is factually accurate, but partial in both senses of the word. The language of PR is often as vague as the content and favours, for example, general quantifiers (many people), hedges (tend to), and lack of detail (a poll in 2005). The false friendless has been dubbed synthetic personalisation or conversationalisation, defined as a ‘tendency to give the impression of treating each of the people handled as an individual’ (Fairclough, 2001, p.52). Synthetic personalisation means that PR is by no means confined to the public sphere, but extends into face-to-face encounters between individuals. Personal persuasion: So far we have dwelt very much on persuasion in the public sphere- in politics and advertising, PR and service encounters- rather than in intimate relations and everyday encounters. While few people make major speeches or launch propaganda campaigns, everyone has had disagreements at home and tried to persuade those close to them to see things differently. These everyday acts of persuasion do not have the expertise and extensive preparation that goes into advertising or political campaigning or service training. They are more likely to be spontaneous and untutored. Erftmier and Dyson (1986) examined the persuasive strategies of children, comparing their informal strategies in speech with those are taught or develop more formally in writing. The first thing to notice here is the dialogic nature of the argument (chapter 1). In other words, this encounter (conversation between mother and her son) is not pre planned, or rehearsed, or informed by theory, as public rhetoric generally is. In the course of an argument, people often find that they have persuaded themselves as much as others. It is not the case, that personal persuasion is dialogic in this way while public rhetoric is entirely monologic. Even the most public persuasion draws on some of the features of faceto-face encounters. Even when there is no actual response from the audience, the shape of a speech is determined by the responses which are assumed by the speaker or writer. There are also formal and public instances of persuasion which are structured in dialogue form. These include adversarial justice. The distinction between public and personal persuasion is by no means straightforward. There are many face-to-face encounters which play out in public spaces, such as supermarkets and law courts, and in which some participants speak on behalf of organisation, rather than individuals. Internet forums are full of exchanges where a point made by one participant is encountered by another as each writer seeks to persuade their fellow discussants of a point of view in process. There is a sense in which the more public formal genres of persuasion evolve out of the more personal ones, both ontogenetically (in our individual lives) and phylogenetically (in society at large). With some important caveats, we might posit two opposite types of persuasion, each with a cluster of characteristics; we could then locate particular instances of persuasion along continua between the two extremes. At one extreme we have persuasion which is carefully planned, formal and serious, and delivered as a monologue, without significant adjustment to interjections from the audience. At the other extreme, we have persuasion which is unplanned, informal and interactive or dialogic. There are plenty of instances of planned and formal speech on the one hand, and unplanned informal writing on the other especially in online and mobile communication. Dimensions of persuasion: Intimacy and affection can determine the ability of the speaker to persuade and the propensity of the listener to be persuaded. There are dimensions here (activity 6.7 p.248) which are likely to be lacking in more public and formal persuasion. It is a sense of closeness which public persuaders, particularly advertisers and PR people, try to emulate- but of which their audiences should be wary. Evaluating persuasion: No other species approaches this ability to share ideas across time and space, or make joint decisions in such large groupings. Language is the unique attribute of our species which underpins these abilities, and some linguists have seen language, and a child’s propensity to acquire the particular language around him, as shaped by these two requirements: to share information and experience, and to form relationships with others (Halliday, 1973). If we take this view of persuasion as an inevitable consequence of a need for collaboration and reaching the best conclusion, then we might also be interested in how to identify the best arguments. We might make a simple contrast between good and bad persuasive arguments. Good persuasion appeals to reason and evidence, laying out its arguments as clearly and elegantly as possible to facilitate the judgment of the audience. Bad persuasion is driven by a lust of power rather than a quest for the general good. It lacks logic and evidence, and confuses and distract its audience with appeals to emotion. In reality, actual instances are likely to combine elements of both extremes. An attempt to understand the processes of argument is found in the enterprise of argumentation theory- which studies how humans do and should reach conclusions through collaborative reasoning (Grootendorst et al., 1996). Thus, an argument can be broken down into components such as the initial claim, the evidence for it, the warrant for making it, exceptions to the claim, and the degree of the commitment in the argument. The criteria for assessing what constitutes a good argument are therefore subject to variation. Another source of variation is cultural difference. The way that cultural differences affect writing is studied under the heading of contrastive rhetoric, which focuses in particular on how students and scholars writing in a second language may be disadvantaged by unfamiliarity with the relevant rhetorical conventions. The best contrastive rhetoric does not simply identify features of texts from a particular place or in a particular language, but relates those features to complex ideologies, values and attitudes that are present in and across cultures. Acknowledgement of contextual and cultural variation in persuasion recognises that attempts to formalise and calculate what makes a good argument are in danger of omitting from analysis a sense of the humanity of persuasion and the role within it of factors other than reason and evidence. Conclusion: In this chapter we have explored the ubiquity of persuasion in human life, in both the most public and the most private of situations, and in different ages, media and cultures. We have seen how many of the issues and strategies in persuasive discourse remain largely unchanged. THANK YOU