Fair Value Reporting During the Financial Crisis of 2007

advertisement

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Fair Value Reporting During the Financial Crisis of 2007-2010:

Evidence from U.S. Publicly Traded Companies

Sylwia Gornik-Tomaszewski, DBA, CMA, CFM

Associate Professor

Department of Accounting and Taxation

Tobin College of Business

St. John's University

8000 Utopia Parkway

Bent Hall - Room 362

Queens, NY 11439

Phone - 718 990-2499

Fax - 718 990-1868

E-mail: gornikts@stjohns.edu

Submitted to: 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference (CBEC)

Sponsored by: Association for Business & Economics Research (ABER)

International Journal of Business & Economics

Oxford Journal

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge University, UK

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

1

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Fair Value Reporting During the Financial Crisis of 2007-2010:

Evidence from U.S. Publicly Traded Companies

ABSTRACT

Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 157, Fair Value Measurements (FAS 157),

issued in September 2006, defines fair value, establishes a framework for measuring fair value,

and expands disclosure about fair value measurements. Some critics blamed FAS 157 for

contributing to the sub-prime mortgage crisis. Supporters, on the other hand, argued that fair

value accounting is merely a reflection of the underlying problem. This study examines FAS 157

fair value disclosures reported by a large sample of U.S. publicly traded companies from 2007 to

2010. Performed analysis indicates limited scope of fair value measurements and provides a new

evidence of reporting asymmetry: on average, fair value assets significantly outweighed fair

value liabilities despite fair value option being in effect. Furthermore, measurement of liabilities

was based on unobservable inputs to a greater degree than measurement of assets. These findings

are true for the financial as well as non-financial entities. In addition, this study contributes

evidence on differences in fair valuation before and after the turning point in the financial crisis

in the mid-2009. Fair value assets as percentage of total assets and fair value liabilities as

percentage of total liabilities increased after June 2009. The percentage of fair value assets

measured based on unobservable inputs declined. These results can be attributed to improved

liquidity and stabilization in the markets after June 2009. Contrary to expectations, however, the

percentage of fair value liabilities measured based on unobservable inputs increased significantly

after June 2009. These results have implications for investors, auditors, and educators.

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

2

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

INTRODUCTION

The recent financial crisis has led to a major debate about fair-value accounting. Many critics

argue that fair-value accounting, and especially its mark-to-market form, has significantly

contributed to the financial crisis or, at least, made it worse (see, e.g., Ely (2009), Forbes (2009),

and Wallison (2008)). From a few-years perspective we can say now that a lot of this criticism

resulted from unfortunate timing of the release of fair value accounting standards by the

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), and was politically motivated.

In September 2006, FASB issued Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 157, Fair

Value Measurements (FAS 157), now codified in the FASB Accounting Standards

CodificationTM Topic 820 (ASC 820).1 The standard does not increase the use of fair value

measurement, but instead provides a uniform authoritative definition of fair value, establishes a

framework for measuring fair value, and expands disclosure about fair value measurements. Six

months later FASB issued FAS 159, The Fair Value Option for Financial Assets and Financial

Liabilities, Including an Amendment of FASB Statement No. 115, now codified in ASC 825,

which applies to measurements for stocks, bonds, loans, warranty obligations and interest rate

hedges, and provides entities the option (but not the requirement) to measure at fair value such

financial instruments and certain other items that are not required to be measured at fair value.

The stated objective of FAS 159 is “to improve financial reporting by providing entities with the

opportunity to mitigate volatility in reported earnings caused by measuring related assets (such

as loans held for sale) and liabilities (such as forward sales commitments) differently without

having to apply complex hedge accounting provisions” (FASB, 2007).

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

3

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Shortly after the release of these pronouncements, the subprime mortgage market problems

began to emerge. Companies and particularly financial institutions began to question whether or

not their distress was related to the new accounting standards. Although poor risk management

and faulty investments contributed to the problem, it was easy to blame fair value accounting.

U.S. Chamber of Commerce, American Bankers Association, American Council of Life Insurers,

Financial Services Roundtable, the Council of Federal Home Loan Banks, real estate and home

builders groups, and numerous politicians, among others, complained that the inability of

businesses, investors, and government to properly value assets in inactive disorderly markets has

created uncertainty and a loss of confidence. FAS 157 had a significant impact on fair value

accounting for illiquid securities as prior to this rule companies often cherry-picked information

to support valuations for illiquid positions.2 There were also perceived problems with accounting

rules on impairment of debt and equity securities — and specifically on guidance on “other-thantemporary impairment” — which have contributed to big write downs of assets.

In order to correct the unintended consequences of mark-to-market accounting, the Office of the

Chief Accountant of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the FASB staff jointly

issued a press release on September 30, 2008 — SEC Release 2008-234: SEC Office of the Chief

Accountant and FASB Staff Clarifications on Fair Value Accounting, that provided financial

statement users, preparers, and auditors with clarification on the application of fair value

accounting (Casabona and Shoaf, 2010).

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

4

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

The FASB followed up on October 10, 2008, with the posting of FASB Staff Position (FSP)

FAS 157-3, Determining the Fair Value of a Financial Asset When the Market for That Asset Is

Not Active (ASC 820-10-35). In this staff position FASB advised their constituents that

determining fair value in a dislocated market depends on the facts and circumstances and may

require the use of significant judgment about whether individual transactions are forced

liquidations or distressed sales. Furthermore, the use of the reporting entity’s own assumptions

about future cash flows and appropriately risk-adjusted discount rates is acceptable when

relevant observable inputs are not available (FASB, 2008).

On October 3, 2008, the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (EESA) was signed into

law. The EESA granted authority to the SEC to suspend FAS 157. Section 133 of the Act

mandated that the SEC conduct a study on mark-to-market accounting. The SEC was required to

consider the impact of accounting standards on bank failure, the process used by FASB in

developing accounting standards, and modifications or alternatives to existing standards.

The SEC provided its study, Report and Recommendations Pursuant to Section 133 of the

Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008: Study on Mark-To-Market Accounting, to U.S.

Congress on December 30, 2008. The Commission concluded that existing mark-to-market

accounting should not be suspended. One of the recommendations in the study stated that

“additional measures should be taken to improve the application and practice related to existing

fair value requirements...” This recommendation further noted that “fair value requirements

should be improved through development of application and best practices guidance for

determining fair value in illiquid or inactive markets” (SEC, 2008). Although there are built-in

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

5

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

implementation flexibilities in FAS 157, the SEC’s suggestions for additional guidance included:

(a) how to determine when markets become inactive and thus may require significant adjustment

to transactions or quoted prices; and (b) how to determine if a transaction (group of transactions)

is not orderly but rather forced or distressed. In response to the recommendations FASB issued

several pronouncements addressing the credit crisis and providing additional guidance to companies.3

This study examines FAS 157 fair value disclosures reported by U.S. publicly traded companies

during the first four fiscal periods since the standard have become effective. Data analysis

focuses on three research questions: (1) to what extent assets and liabilities are measured at fair

value, (2) to what extent unobservable inputs are used to measure fair value; and (3) how (1) and

(2) compare before and after the turning-point in the financial crisis in the mid-2009.

The results show evidence of reporting asymmetry: on average, fair value assets significantly

outweigh fair value liabilities. Furthermore, fair value measurement of liabilities is based on

unobservable inputs to a greater degree than fair value measurement of assets. These findings are

true for the financial as well as non-financial entities. Also, the fair value assets and liabilities, as

well as the fair value assets and liabilities categorized as based on unobservable (entitygenerated) inputs differ before and after June 2009.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In next section provisions of FAS 157 and

the implementation guidance are described to provide background for this study. This section

also addresses recent international convergence on fair value measurements. Next, prior

empirical studies on fair value reporting under FAS 157 are discussed, followed by description

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

6

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

of empirical tests and their results. Concluding remarks from the study are offered in the final

section.

BACKGROUND

FASB issued FAS 157 in September 2006 with the objective to increase consistency and

comparability in fair value measurements. FAS 157 does not require any new fair value

measurements but establishes a single definition of fair value and a framework for measuring fair

value. It improves transparency by expending disclosures about fair value measurements.

Single Authoritative Definition of Fair Value

Prior to FAS 157, neither a single coherent definition for fair value nor detailed guidance for

applying the fair value definition existed. This Statement defines fair value as the price that

would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between

market participants at the measurement date (FASB, 2006, ¶5)4. FASB clarifies that the basis for

a fair value measure is an exit price – the price in an orderly transaction between market

participants to sell the asset or transfer the liability in the principal (or most advantageous)

market for the asset or liability; not an entry price – that is the market price at which an asset is

acquired or a liability is assumed.5 The Board affirmed that the transaction to sell the asset or

transfer the liability is an orderly transaction, not a forced transaction (for example, if the seller is

experiencing financial difficulty). The transaction to sell the asset or transfer the liability is a

hypothetical transaction at the measurement date. Therefore, regardless of the management intent

to hold or sell the asset or transfer the liability, the definition focuses on the exit price.

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

7

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Valuation Techniques

FASB indicates that three valuation techniques could be used to measure fair value: market

approach, income approach, and cost approach. The market approach uses prices and other

relevant information generated by market transactions involving identical or comparable assets

and liabilities. This valuation technique, also referred to as the mark-to-market approach, utilizes

an unadjusted market quoted price for the security available from the financial press or other

sources. When a security has no readily available direct market quote but quotes are available for

similar securities, relative value analysis or a matrix pricing approach may be used. This

approach may utilize a simple price interpolation or involve more complex analysis or

algorithms. A consensus price derived from several quoted prices may be also useful.

The income approach uses valuation techniques to convert future amounts, such as cash flows or

earnings, to a single discounted present amount. Also referred to as mark-to-model approach, the

technique involves the application of mathematical models that are calibrated to market quoted

prices and reflect current market expectations about future amounts. Those valuation techniques

include present value techniques; option-pricing models, such as the Black-Scholes-Merton

formula and a binomial model.

Finally, the cost approach is based on the current replacement cost that is the amount that

currently would be required to replace the service capacity of an asset. From the perspective of a

market participant (seller), the price that would be received for the asset is determined based on

the cost to a market participant (buyer) to acquire or construct a substitute asset of comparable

utility, adjusted for obsolescence.

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

8

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

FASB encourages use of multiple valuation techniques, if needed. The board also suggests, that

although valuation techniques used to measure fair value should be applied consistently, a

change in a valuation technique or its application is appropriate if the change results in a

measurement that is equally or more representative of fair value (FASB 2006).

Fair Value Hierarchy

The Statement established a fair value hierarchy with the purpose to prioritize the market inputs

to valuation techniques used to measure fair value into three broad levels.6 The availability of

market inputs relevant to the asset or liability and the faithful representation of the inputs may

affect the selection of appropriate valuation techniques. However, the fair value hierarchy

focuses on the market inputs to valuation techniques, not the valuation techniques themselves

(Casabona & Shoaf, 2007). Fair value is a market-based measurement, not an entity-specific

measurement. Therefore, a fair value measurement should be determined based on the

assumptions that market participants would use in pricing the asset or liability. As a basis for

considering market participant assumptions in fair value measurements, FAS 157 establishes a

fair value hierarchy that distinguishes between (1) inputs that reflect market participant

assumptions developed based on market data obtained from sources independent of the reporting

entity (observable inputs); and (2) inputs that reflect the reporting entity’s own assumptions

about market participant assumptions developed based on the best information available in the

circumstances (unobservable inputs). The notion of unobservable inputs was intended by FASB

to allow for situations in which there is little, if any, market activity for the asset or liability at

the measurement date.

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

9

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Observable inputs are classified into Levels 1 and 2. Level 1 inputs are unadjusted quoted prices

in active markets for identical assets or liabilities that the reporting entity has the ability to access

at the measurement date. An active market for the asset or liability is a market in which

transactions for the asset or liability occur with sufficient frequency and volume to provide

pricing information on an ongoing basis. Level 2 inputs are other directly or indirectly

observable inputs, such as (FASB, 2006):

a. Quoted prices for similar assets or liabilities in active markets;

b. Quoted prices for identical or similar assets or liabilities in markets which are not active;7

c. Inputs other than quoted prices that are observable for the asset or liability, such as

interest rates and yield curves observable at commonly quoted intervals, volatilities, prepayment

speeds, loss severities, credit risks, and default rates; and

d. Inputs that are derived principally from or corroborated by observable market data by

correlation or other means (market-corroborated inputs).

Unobservable Level 3 inputs should be used to measure fair value to the extent that observable

inputs are not available. However, the fair value measurement objective remains the same, that

is, an exit price from the perspective of a market participant that holds the asset or owes the

liability. Unobservable inputs should be developed based on the best information available in the

circumstances, which might include the reporting entity’s own data. In developing unobservable

inputs, the reporting entity need not undertake all possible efforts to obtain information about

market participant assumptions. However, the reporting entity shall not ignore information about

market participant assumptions that is reasonably available without undue cost and effort.

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

10

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

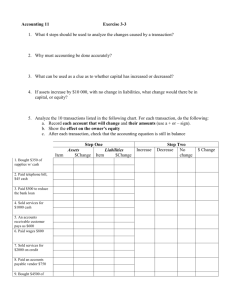

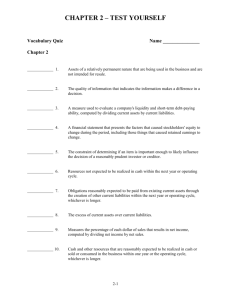

Table 1 summarizes the fair value hierarchy providing examples of inputs at each of the three

levels and instruments which could be valued using these inputs. Furthermore, the inputs are

linked to the respective valuation techniques (approaches).

{TABLE 1 ABOUT HERE}

FAS 157 expands disclosures about the use of fair value to measure assets and liabilities in

interim and annual periods subsequent to initial recognition. Disclosures about fair value

measurements are designed to provide users of financial statements with additional transparency

regarding the extent to which fair value is used to measure assets and liabilities, valuation

techniques, inputs and assumptions used in measuring fair value, and effect on earnings.

Additional Implementation Guidance

During 2009 FASB, responding to criticism, issued two pieces of guidance clarifying

requirements of FAS 157. The first was FSP FAS 157-4, Determining Fair Value When the

Volume and Level of Activity for the Asset or Liability Have Significantly Decreased and

Identifying Transactions That Are Not Orderly, and the second Accounting Standards Update

(ASU) 2009-05, Measuring Liabilities at Fair Value. FSP FAS 157-4 affirms the core principles

of FAS 157 and provides additional guidance in determining when observable transaction prices

or quoted prices in markets that have become less active require significant adjustment to

estimate fair value.8 It became effective for interim and annual reporting periods ending after

June 15, 2009, although early adoption was permitted for periods ending after March 15, 2009.

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

11

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

FASB reaffirmed that further analysis and significant judgment may be necessary to estimate fair

value, especially in circumstances where the volume and level of activity has significantly

decreased. In addition, multiple valuation techniques may be appropriate for estimating fair

value. The reasonableness of the range of fair value estimates resulting from multiple techniques

must be considered with the objective of determining the point within the range that is most

representative of fair value under current market conditions.

The FSP FAS 157-4 provides examples of factors to be considered in determination whether

there has been a significant decrease in the volume and level of activity for the asset or liability

compared with normal market activity, such as few recent transactions, price quotations are not

based on current information, and price quotations vary substantially over time or among market

makers (FSP FAS 157-4, ¶12). If it is concluded that there has been a significant decrease in the

volume and level of activity in relation to normal market activity, then observable transaction

prices may not be determinative of fair value, further analysis is needed and a significant

adjustment to such prices may be necessary to estimate fair value.

In the next step an evaluation should be made whether the transaction is orderly. This evaluation

would be based on the weight of the evidence because even if there has been a significant

decrease in the volume and level of activity, it should not be concluded that all observable

transactions are not orderly (that is, distressed or forced). The FSP FAS 157-4 provides examples

of characteristics of transactions that are not orderly. If, based on weight of evidence, an entity

concludes that the transaction is not orderly than little, if any, weight is assigned to the

transaction in estimating fair value. The FSP FAS 157-4 also requires additional disclosures for

interim and annual periods for equity and debt securities by major security type.

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

12

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

The second major pronouncement was ASU 2009-05, finalized in August 2009, which clarified

FAS 157’s guidance on the fair value measurement of liabilities. The ASU 2009-05 emphasized

the importance of maximizing the use of relevant observable inputs and minimizing the use of

unobservable inputs, regardless of the method employed (Casabona and Shoaf, 2010).

Recent Developments in Fair Value Accounting

On May 12, 2011 FASB and the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) completed

their Fair Value Measurement joint convergence project by issuing guidance on fair value

measurement and disclosure heralded in a press release as “largely identical” across International

Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (U.S.

GAAP) (FASB, 2011). The guidance is set out in IFRS 13, Fair Value Measurement, and FASB

ASU 2011-04, Fair Value Measurement (Topic 820)—Amendments to Achieve Common Fair

Value Measurement and Disclosure Requirements in U.S. GAAP and IFRSs. The boards stated

that the harmonization of fair value measurement and disclosure requirements internationally

forms an important element of the boards’ response to the global financial crisis.

Like FAS 157, the new standards do not extend the use of fair value accounting, but provide

guidance on how it should be applied where its use is already required or permitted by other

standards within IFRS or U.S. GAAP. For IFRS, IFRS 13 will improve consistency and reduce

complexity by providing, for the first time, a precise definition of fair value and a single source

of fair value measurement and disclosure requirements for use across IFRS. For U.S. GAAP,

ASU 2011-04 supersedes most of the guidance in FASB ASC Topic 820 although many of the

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

13

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

changes are clarifications of existing guidance or wording changes to align with IFRS 13. It also

reflects FASB’s consideration of the different characteristics of public and nonpublic entities and

the needs of users of their financial statements. Nonpublic entities will be exempt from a number

of the new disclosure requirements.

REVIEW OF PRIOR STUDIES ON FAIR VALUE REPORTING UNDER FAS 157

The relation between fair value applications and economic cycles has been discussed in many

studies (see, e.g., Enria et al. (2004) and Novoa et al. (2009)). This literature review is limited to

studies focusing on fair value reporting under FAS 157.

Several empirical studies concentrated on fair value hierarchy under FAS 157; some researchers

investigated value relevance of inputs used to derive the fair value of an asset or liability. Using

quarterly reports of banking firms in 2008, Song et al. (2010) found that the value relevance of

Level 1 and Level 2 fair values is greater than the value relevance of Level 3 fair values. They

also produced evidence that the value relevance of fair values (especially unobservable Level 3

fair values) is greater for firms with strong corporate governance.

Bhamornsiri et al. (2010) examined disclosures on fair value measurements, required by FAS

157, in quarterly reports (Form 10-Q’s) issued by the Fortune 500 companies for quarter ended

March 31, 2008. Their results show that a large majority of inputs are observable. More

specifically, 93.5% of the sample financial assets and 93.1% of the sample financial liabilities

were measured by Level 1 or 2 inputs.

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

14

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Laux and Leuz (2010) examined the role of fair-value accounting in the financial crisis using

descriptive data and empirical evidence. They concluded that it is unlikely that fair-value

accounting added to the severity of the 2008 financial crisis in a major way. While there may

have been downward spirals or asset-fire sales in certain markets, Laux and Leuz (2010) find

little evidence that these effects were the result of fair-value accounting. They also find little

support for claims that fair-value accounting led to excessive write-downs of banks' assets. If

anything, empirical evidence to date points in the opposite direction, that is, toward the

overvaluation of bank assets during the crisis.

While previous studies on fair value reporting under FAS 157 concentrate on financial

institutions and fair value assets, this study expands the analysis to all U.S. publicly traded

companies representing cross-section of industries, and compares reported fair value assets and

fair value liabilities. Moreover, because several years past since FAS 157 became effective,

analysis of changes in reported fair values over the period 2007-2010 is performed.

EMPIRICAL STUDY

Sample Selection

The data was obtained from Compustat (North America – Fundamentals Annual). The sample

covers fiscal years 2007 to 2010. The data was collected within a date range November 2007 to

May 2011. FAS 157 became effective for fiscal years beginning after November 15, 2007 9 and

2010 was the last fiscal year for which data were available in Compustat at the time the analysis

was performed. The date range was extended to early months of 2011 to include as many

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

15

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

companies with fiscal year ends other than December 31, as possible. Companies with foreign

incorporation code were excluded from the sample.

There were 27,187 observations collected from the Industrial files (INDL),10 adjusted as follows.

First, 5,571 observations were deleted with missing values for total assets or total liabilities.

Next, 11,259 observations were deleted with missing values under all levels in the fair value

hierarchy. The elimination process produced a final sample of 10,357 observations included in

the analysis.

Research Design and Results

To examine the extent of fair value reporting during the period 2007-2010, two variables were

created. The first variable, FVA, measures assets reported at fair value as percentage of total

assets. It is computed as follows: 11

FVA = [(AQPL1 + AOL2 + AUL3)/AT] * 100

(1)

where:

AQPL1 - Level 1 Assets (Quoted Prices);

AOL2 - Level 2 Assets (Observable);

AUL3 - Level 3 Assets (Unobservable);

AT – Total Assets.

The second variable, FVL, measures liabilities reported at fair value as percentage of total

liabilities. It is computed as follows:

FVL = [(LQPL1 + LOL2 + LUL3)/LT] * 100

(2)

where:

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

16

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

LQPL1 - Level 1 Liabilities (Quoted Prices);

LOL2 - Level 2 Liabilities (Observable);

LUL3 - Level 3 Liabilities (Unobservable);

LT – Total Liabilities.

To examine the extent of reliance on unobservable (entity-generated) inputs during the period

2007-2010, two variables were created. The first variable, Level 3_Assets, represents Level 3

assets as percentage of total fair value assets. The variable is computed as follows:

Level 3_Assets = (AUL3/TotalFVA) * 100

(3)

where:

AUL3 - Level 3 Assets (Unobservable), and

TotalFVA = AQPL1 + AOL2 + AUL3.

The second variable, Level 3_Liabilities, represents Level 3 liabilities as percentage of total fair

value liabilities:

Level 3_Liabilities = (LUL3/TotalFVL) * 100

(4)

where:

LUL3 - Level 3 Liabilities (Unobservable), and

TotalFVL = LQPL1 + LOL2 + LUL3.

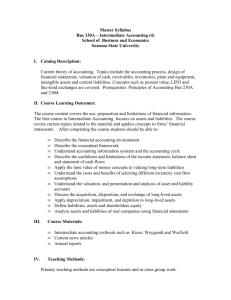

Figure 1 presents graphically mean values for these variables per year. The vertical numbers on

the columns represent number of observations on which each mean ratio (percentage) is based.

Because the data is derived from annual reports, these numbers also represent number of

companies which reported fair value measurements.

{FIGURE 1 ABOUT HERE}

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

17

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

On average, compare to total assets, fair value assets dropped from 22.6 percent in 2007 to 18.4

percent in 2010. Compare to total liabilities, fair value liabilities dropped from 14.1 percent in

2007 to 4.6 percent in 2010.12

On average, compare to total fair value assets, Level 3 assets oscillated between 9.8 percent in

2007 and 8.0 percent in 2010, with a peak of 12.3 percent in 2008. This is somewhat consistent

with Laux and Leuz (2010) who observed that transfers of assets by U.S. banks to Level 3

category were substantial and took place early in the financial crisis.13 Compare to total fair

value liabilities, Level 3 liabilities jumped from 9.4 percent in 2007 to 22.4 percent in 2009, and

later declined slightly to 20.9 percent in 2010.

Data presented in Figure 1 lead to at least two conclusions: first, for U.S. publicly traded

companies FVA are significantly greater than FVL, despite fair value option being in effect; and

second, U.S. publicly traded companies use unobservable inputs to measure liabilities more often

than they use such inputs to measure assets. This may result from unavailability of observable

inputs as well as from the higher risk factor affecting negatively present value of liabilities.14

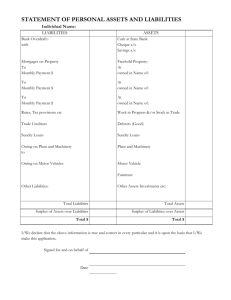

Figure 2 presents means for the same four variables as Figure 1, but only for a subsample of

finance, insurance and real estate companies.

{FIGURE 2 ABOUT HERE}

Pattern emerging from Figure 2 is very similar to pattern presented in Figure 1. Percentage of

fair value assets significantly outweighs percentage of fair value liabilities and more liabilities

are classified in Level 3 than assets. Compare to total assets, the mean fair value assets dropped

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

18

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

from 27.3 percent in 2007 to 23.8 percent in 2008. Over the next two years the percentage

increased to 24.8 percent in 2009 and 26.8 percent in 2010. Compare to total liabilities, the mean

fair value liabilities dropped from 15.7 percent in 2007 to 4.1 percent in 2010.

Compare to total fair value assets, the mean Level 3 assets oscillated between 9.1 percent in 2007

and 9.4 percent in 2010, with the highest mean of 11.9 percent in 2009. Compare to total fair

value liabilities, the mean Level 3 liabilities jumped from 7.2 percent in 2007 to 22.2 percent in

2008 and later increased again to 22.5 percent in 2010.

These means are higher than those reported by Song et al. (2010) in their study based on 1,260

firm-quarters representing banking industry in 2008. Their mean ratios of fair value assets and

liabilities to total assets and liabilities were about 15 percent and 0.4 percent, respectively. The

means presented above are lower, however, than those reported by Laux and Leuz (2010) and

Bhamornisiri et al. (2011). Laux and Leuz (2010) report that three major U.S. investment banks

measured about 45 percent of their assets at fair value in 2007 Q1, and increased the fair value

component to 55.2 percent in 2009 Q1. As for the four major bank holding companies, the fair

value assets percentage oscillated between 32.4 percent in 2007 Q1 and 31.6 percent in 2009 Q1.

Bhamornisiri et al. (2011) collected data for Fortune 500 companies that issued quarterly reports

dated March 31, 2008. These companies reported 51 percent of assets and 23 percent of

liabilities at fair value. Bhamornisiri et al. (2011) findings add evidence supporting a notion of

asymmetry between fair value assets and fair value liabilities.

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

19

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

In the next stage of the analysis tests are designed to determine whether there were any

significant changes in the fair value disclosures over the period 2007-2010. The financial crisis

officially ended in the mid-2009, although we still experience aftershocks and the global

financial and economic situation is far from being stable. Also, as previously discussed, in 2009

FASB issued FSP FAS 157-4, which became effective June 15, 2009. Therefore it is expected

that the reporting of fair value assets and liabilities may have changed after the mid-2009, as

compared to the period 2007-2008 marked by severe financial crisis and luck of sufficient

guidance on the implementation of requirements of FAS 157 in inactive and disorderly markets.

To examine the potential differences the following four hypotheses are set in an alternative form:

Ha1: μD1 ≠ 0

(5)

Where D1 = FVA07/09-03/11 - FVA11/07-06/09

Ha2: μD2 ≠ 0

(6)

Where D2 = Level 3_Assets07/09-03/11 – Level 3_Assets11/07-06/09

Ha3: μD3 ≠ 0

(7)

Where D3 = FVL07/09-03/11 - FVL11/07-06/09

Ha4: μD4 ≠ 0

(8)

Where D4 = Level 3_Liabilities07/09-03/11 – Level 3_Liabilities11/07-06/09

All the hypotheses are non-directional because of contradictory factors influencing fair value

reporting during the test period. For example, although FSP FAS 157-4 provided a clear

guidance as to the implementation of FAS 157 and recommended transfers from Level 2 inputs

to Level 3 inputs under certain circumstances, it became effective on June 15, 2009, when the

financial crisis showed signs of abatement and the financial market conditions improved, making

the use of Level 3 inputs less critical.

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

20

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

To test the hypotheses Ha1 to Ha4, the paired-difference tests were used. First, the datasets for

each fiscal year were sorted by CUSIP number,15 and then merged by CUSIP into one dataset.

This dataset consisted of records for each company containing all the fair values disclosed in the

company’s annual reports during the period 2007-2010. Several ‘Before’ and ‘After’ variables

were created in the following manner: information derived from annual reports issued by

companies between November 30, 2007 and June 15, 2009 fell into ‘Before’ category while

information derived from reports issued after June 15, 2009 fell into an ‘After’ category.16

Paired observations were tested using both, parametric paired-difference t-test and nonparametric Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test. Although each pair of measurements is independent of

other pairs, the differences appear not to be from a normal distribution. Therefore outcomes from

the Wilcoxon Signed Rank test are more reliable.

Table 2 contains descriptive statistics for four ‘Before’ and ‘After’ categories: FVA, Level

3_Assets, FVL, and Level 3_Liabilities. Mean Differences between ‘Before’ and ‘After’

variables are also reported as well as the paired-difference tests results. The goal of this analysis

is to determine whether the average change from ‘Before’ to ‘After’ is larger than could happen

by chance alone.

{TABLE 2 ABOUT HERE}

There were 1,301 paired differences available to test hypotheses Ha1 and Ha2, and 818 paired

differences to test hypotheses Ha3 and Ha4. The results are statistically significant and provide

support to reject null hypotheses H02, H03 and H04 at the 1% significance level, and null

hypotheses H01 at the 5% significance level. It can be concluded that the average differences for

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

21

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

FVA, Level 3_Assets, FVL, and Level 3_Liabilities are significantly different from zero. In

other words, fair value assets and liabilities, as compared to total assets and liabilities, and Level

3 assets and liabilities, as compare to total fair value assets and liabilities, are significantly

different before and after June 15, 2009. From the paired observations it could be concluded that

after June 15, 2009 fair value assets and liabilities constituted higher percentage of total assets

and liabilities, respectively, and fewer assets were measured based on unobservable inputs. This

would be consistent with improved market conditions and increase liquidity after June 2009. The

most interesting result, however, is a greater reliance on models based on unobservable inputs for

measurement of fair value liabilities after June 2009. This should be a matter of concern for

investors and regulators alike, as the research shows that the level of informativeness of fair

values is affected by the amount of measurement error and source of the estimates (Landsman,

2007).

Overall, the mismatch between assets and liabilities at fair value reported in other studies is also

observable here, with significant excess of fair value assets over fair value liabilities. Further

analysis and testing would be needed to gain insight into the changing patterns of reporting fair

value by U.S. companies over a longer period of time and under changing economic conditions.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Fair value accounting endured unprecedented attack over the past few years. Many have called

for it suspension altogether. Evidence have shown that fair value accounting played a limited

role in U.S. banks’ problems during the recent financial crisis, except for few banks with large

trading positions (Laux and Leuz, 2010).

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

22

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

This study has contributed to the literature by showing the extent of fair value measurements as

applied and reported by a cross-section of U.S. publicly traded companies during the period

2007-2010. A spotlight was cast on the fair value measurements categorized within Level 3

assets and liabilities. The assessment of the Level 3 items is very important for users of financial

statements as it entails use of valuation techniques and data that may not be verifiable as a great

deal of assumptions and estimates are involved. Another contribution of this study is empirical

evidence on changes in reported fair values before and after mid-2009.

The results show that, on average, fair value assets, and particularly fair value liabilities, are

limited in scope, even when reported by financial institutions. Fair value measurements are based

primarily on observable inputs, only valuation of liabilities utilizes the income approach with

unobservable inputs to a greater degree. This may result from limited trading of liabilities.

Another finding from the study is that fair value assets and liabilities, as compared to total assets

and liabilities, and Level 3 assets and liabilities, as compared to total fair value assets and

liabilities, are significantly different before and after June 2009. Congruent with the overall

improvement of the economy and liquidity of the markets after June 2009, fair value assets and

fair value liabilities increased, while percentage of fair value assets classified in Level 3

declined; contrary to expectations, however, greater percentage of fair value liabilities were

classified in Level 3 after June 1009.

This study looked at the big picture and was based on a large sample of U.S. publicly traded

companies representing a cross-section of industries. In addition, finance, insurance and real

estate companies were analyzed separately. In the future studies consideration should be given to

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

23

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

confounding factors differentiating entities, such as size, industry, financial position and

performance during the financial crisis. Further research is required into the fair value

disclosures to understand management judgments as well as the impact of fair value

measurements on investors and other financial statement users.

Although data presented in this study indicates that, on average, only about one fifth of assets

and less than one twentieth of liabilities are currently measured at fair value, fair value

accounting is here to stay and most probably expand. FASB and IASB has recently converged on

fair value measurements and achieved a high quality standard. But this is an area of accounting

characterized by inherent complexity where significant judgments are required. Especially when

assets and liabilities are not traded in active and orderly markets and valuation is based on

unobservable inputs, an understanding of complex valuation models and subjective assumptions

is needed. Reliance on third party valuation experts, engaged by management and/or audit teams,

is common in these situations. Question arises whether this is the optimum modus operandi for

the accounting profession or more extensive education and training on valuation techniques

should be provided at the university and/or firm level.

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

24

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

REFERENCES

Bhamornsiri, S., Guinn, R. E., & Schroeder, R. G. (2010). The economic impact of SFAS No.

157. International Advances in Economic Research 16: 65-79.

Carcello, J. & Williams, J. (2004). Fair value measurements. Miller GAAP Update Service 4

(17): 2-3.

Casabona, P., & Shoaf, V. (2007). New requirements for measuring and reporting fair value in

GAAP. Review of Business 27(4): 10-18.

Casabona, P., & Shoaf, V. (2010). Fair value accounting and the credit crisis. Review of Business

30 (2): 19-30.

Cascini, K.T., & DelFavero, A. (2011). An evolution of the implementation of fair value

accounting: Impact on financial reporting. Journal of Business & Economic Research 9(1): 1-16.

Ely, B. (2009). Bad rules produce bad outcomes: Underlying public-policy causes of the U.S.

financial crisis. Cato Journal 29.1 (Winter 2009): 93-114.

Enria, A., Capiello, L., Dierick, Grittini, S., Haralambous, A., Maddoloni, A., Molitor, P., Pires,

F., & Poloni, P. (2004). Fair value accounting and financial stability. European Central Bank

Occasional Paper Series, No: 13.

Financial Accounting Standards Board. (2006). Fair value measurements. Statement of Financial

Accounting Standards No. 157, Norwalk, CT: FASB.

___________. (2007). The Fair value option for financial assets and financial liabilities,

including an amendment of FASB Statement No. 115. Statement of Financial Accounting

Standards No. 159, Norwalk, CT: FASB.

___________.(2008). Determining the fair value of a financial asset when the market for that

asset is not active. FASB Staff Position (FSP) FAS 157-3. Norwalk, CT: FASB.

___________. (2009). Determining fair value when the volume and level of activity for the asset

or liability have significantly decreased and identifying transactions that are not orderly. FASB

Staff Position (FSP) No. 157-4. Norwalk, CT: FASB.

___________.(2011). News release May 12, 2011: IASB and FASB issue common fair value

measurement and disclosure requirements Norwalk, CT: FASB.

Forbes. S. (2009). End mark-to-market. Forbes.com, March 29, 2008.

Landsman, W.R. (2007). Is fair value accounting information relevant and reliable? Evidence

from capital market research. Accounting and Business Research Special Issue: International

Accounting Policy Forum: 19-30.

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

25

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Laux C. & Leuz C. (2010). Did fair-value accounting contribute to the financial crisis? Journal

of Economic Perspectives 24 (1): 93-118.

Novoa, A., Scarlata, J. and Sole, J. (2009). Procylicality and fair value accounting, IMF Working

Paper No: 09/39.

OTC Valuations, Inc. (2007). FAS 157 – derivative valuation insights™, an OTC Valuations

White Paper, November 2007.

Robak, E. (2009). Fair value is here to stay. The CPA Journal 79 (10): 6-9.

Securities and Exchange Commission. (2008). Report and recommendations pursuant to section

133 of the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008: Study on mark-to-market accounting.

Office of the Chief Accountant Division of Corporation Finance, United States Securities and

Exchange Commission, Washington DC: December 30, 2008.

Song, C.J, Thomas W.B. and Yi, H. (2010). Value relevance of FAS No. 157 fair value hierarchy

information and the impact of corporate governance mechanism. The Accounting Review 85(4):

1375-1410.

Wallison, P.J. (2008). Judgment too important to be left to the accountants. Financial Times,

May 1, 2008.

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

26

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Table 1: Fair value hierarchy – examples and links to valuation approaches

Source: OTC Valuations, Ltd., 2007.

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

27

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Table 2: Descriptive statistics and paired-differences test results

Variable

N

Mean

Standard

Deviation

FVA Reported After

June 15, 2009 (A1)

FVA Reported

Before June 15,

2009 (B1)

Difference = A1-B1

2,795

20.47

21.30

1,312

19.94

15.05

1,301

2.55

24.72

Level 3_Assets

Reported After June

15, 2009 (A2)

Level 3_Assets

Reported Before

June 15, 2009 (B2)

Difference = A2-B2

2,795

8.78

20.07

1,312

60.30

21.42

1,301

-52.02

28.28

FVL Reported After

June 15, 2009 (A3)

FVL Reported

Before June 15,

2009 (B3)

Difference = A3-B3

1,714

9.45

17.97

831

4.98

10.91

818

7.67

21.17

Level 3_Liabilities

Reported After June

15, 2009 (A2)

Level 3_Liabilities

Reported Before

June 15, 2009 (B2)

Difference = A4-B4

1,714

19.00

30.54

831

8.68

17.99

818

13.72

31.96

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

Paired-Difference Test

t-test

Wilcoxon

Signed Rank

Test

3.7175

(p=0.002)

36,360.5

(p=0.0073)

-66.33

(p<.0001)

-390,998

(p<.0001)

10.37

(p<.0001)

86,726

(p<.0001)

12.27

(p<.0001)

37,631.5

(p<.0001)

28

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Figur 1: Mean values for FVA, Level 3_Assets, FVL and Level 3_ Liabilities

during the period 2007-2010 – all companies

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

29

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Figure 2: Mean values for FVA, Level 3_Assets, FVL and Level 3_ Liabilities

during the period 2007-2010 - finance, insurance and real estate companies (SIC

code: 6011-6799).

1

In the paper I continue to refer to the standard as FAS 157, rather than ASC 820, as the study covers mostly the

pre-codification period (FASB ASC is effective for interim and annual periods ending after September 15, 2009).

2

Under FAS 157 companies are required to consider all “reasonably available” information and use the best data

available to support their market assumptions (Robak, 2009).

3

The most prominent among them are: FSP FAS 157-4 (ASC 820-10), Determining Fair Value When the Volume

and Level of Activity for the Asset or Liability Have Significantly Decreased and Identifying Transactions That Are

Not Orderly; FSP FAS 107-1 and APB 28-1(ASC 825-10), Interim Disclosures about Fair Value of Financial

Instruments, FSP FAS 115-2 and FAS 124-2 (ASC 320-10), Recognition and Presentation of Other-ThanTemporary Impairment; and ASU 2009-05, Measuring Liabilities under FASB Statement 157.

4

FASB ASC 820-10-20 (Glossary)

5

Carcello and Williams (2004) suggested that FAS 157 might have affected or amended as many as 30 previously

issued accounting standards. Robak (2009) determined that FAS 157 amended, deleted, or otherwise affected more

than 40 areas of accounting guidance.

6

The term “input” is meant to refer broadly to the assumptions that market participants would use in pricing the

asset or liability, rather than the more narrow consideration of only actual data entered into a pricing model.

7

Not active markets means markets in which there are few transactions for the asset or liability, the prices are not

current, or price quotations vary substantially either over time or among market makers, or in which little

information is released publicly.

8

FSP FAS 157-4, issued April 9, 2009, superseded FSP FAS 157-3, Determining the Fair Value of a Financial

Asset When the Market for That Asset Is Not Active.

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

30

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

9

FASB Staff Position (FSP) FAS 157-2, Effective Date of FASB Statement No. 157, amended FAS 157 to delay the

effective date of FAS 157 for nonfinancial assets and nonfinancial liabilities, except for items that are recognized or

disclosed at fair value in the financial statements on a recurring basis (at least annually) until fiscal years beginning

after November 15, 2008.

10

Financial Services files (FS) do not contain any FAS 157 data. The FAS 157 inputs for the financial institutions,

as for all other companies, were collected from the INDL files.

11

Alternatively, variable Total Fair Value Assets (TFVA) could be use in this study, but because it equals the sum

of assets under Levels 1, 2, and 3, plus any "netting" or other adjustments (including assets measured at fair value discontinued operations), sum of fair values classified under Levels 1, 2 and 3 is used instead.

12

Results for 2007 should be interpreted with caution for two reasons: (1) they are based on a very limited number

of observations, and (2) FSP FAS 157-2 delayed the effective date of FAS 157 for nonfinancial assets and liabilities

recognized and disclosed at fair value on nonrecurring basis until after November 15, 2008.

13

By the first quarter of 2008, the cumulative net transfers into Level 3 amounted to over 50 percent for the three

largest investment banks (Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and Merrill Lynch) and to over 80 percent for the four

largest bank holding companies (JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, Citigroup, and Wells Fargo) relative to the

original balance of Level 3 assets in the first quarter of 2007.

14

Cascini and DelFavero (2011) discuss the counterintuitive impact of fair value accounting on liabilities. If a

company encounters financial difficulties the increased default risk results in decrease in the present value of the

debt instruments (such as bonds or notes) generating gains to income.

15

CUSIP number is a nine-character number that uniquely identifies a particular security.

16

For companies operating on a calendar year and those with fiscal year end on or after June 30, data derived from

2007 and 2008 annual reports were classified as ‘Before’ and data derived form 2009 and 2010 reports were

classified as ‘After.’ For companies with the fiscal year end falling before June, however, the ‘After’ category

consisted only of the 2010 data and the ‘Before’ category consisted of 2007, 2008 and 2009 data.

June 27-28, 2012

Cambridge, UK

31