Theoretical foundations and early research

advertisement

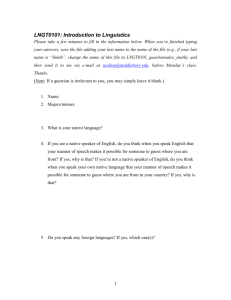

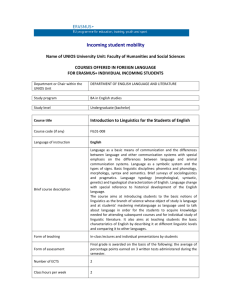

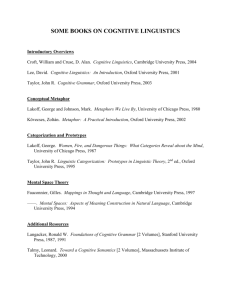

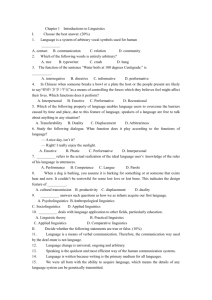

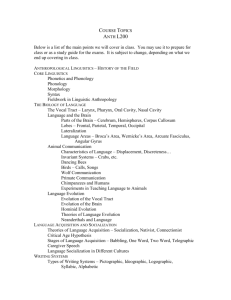

Introduction to Cognitive Linguistics Graduate Institute of Linguistics Fu-Jen University 2005 Lecture 1 September 28, 2005 Overview of the course; Theoretical foundations and early research: The importance of theory, history, and research methods Required readings: de Saussure, F. (1972). Linguistic value. In C. Bally & A. Sechehaye (eds.), Course in general linguistics. Open Court La Salle, Illinois. pp. 111-120 Wang, W. S-Y. (1978). The Three Scales of Diachrony. In B. B. Kachru (ed.). Linguistics in the Seventies: Directions and Prospects. Department of Linguistics, University of Illinois. pp. 63-76. Dirven, R. & Verspoor, M. (1998). Cognitive Exploration of Language and Linguistics. Amsterdam: Benjamins. Chapter 1: The cognitive basis of language: language and thought. pp. 1-24 Recommended readings: Evans, V., & Green, M. (2005). Introduction to Cognitive Linguistics. Chapter 1. pp. 1-33. Janda, L. (2000). Cognitive Linguistics. SLING2K Position Paper What is Cognitive Linguistics • Cognitive Linguistics is a new approach to the study of language that emerged in the 1970’s as a reaction against the dominant generative paradigm (Ruiz de Mendoza 1997). – Some of the main assumptions underlying the generative approaches to syntax and semantics are not in accordance with the experimental data in linguistics, psychology and other fields – E.g., Mental images, general cognitive processes, basic-level categories, prototype phenomena, the use of neural foundations for linguistic theory and so on, are not considered part of these grammars. The Line of Research in Cognitive Linguistics • To examine the relation of language structure to things outside language: – cognitive principles and mechanisms not specific to language • including principles of human categorization • pragmatic and interactional principles • functional principles in general – e.g., iconicity and economy • Cognitive Linguistics is not a totally homogeneous framework. • Three main approaches: – Experimental view – the Prominence view – the Attentional view of language (Ungerer and Schmid, 1997) The Experiential view • This view pursues a more practical and empirical description of meaning • It is the user of the language who tells us what is going on in their minds when they produce and understand words and sentences. • The first research within this approach - the study of cognitive categories led to the prototype model of categorisation (Eleanor Rosch et al.,1977, 1978) • The knowledge and experience human beings have of the things and events that they know well is transferred to those other objects and events, which they are not so familiar with, and even to abstract concepts. • Lakoff and Johnson (1980) were among the first ones to pinpoint this conceptual potential, especially in the case of metaphors. The Prominence view • It is based on concepts of profiling and figure/ground segregation, a phenomenon first introduced by the Danish gestalt psychologist Rubin (1886-1951). • The prominence principle explains why, when we look at an object in our environment, we single it out as a perceptually prominent figure standing out from the ground. – This principle can also be applied to the study of language; especially, to the study of local relations (cf. Brugman 1981, 1988; Casad 1982, 1993; Lindner 1982; Herskovits 1986; Vandeloise 1991; among others). – It is also used in Langacker’s (1987, 1991) grammar, where profiling is used to explain grammatical constructs and, figure and ground for the explanation of grammatical relations. Figure-ground is another Gestalt psychology principle. It was first introduced by the Danish phenomenologist Edgar Rubin (1886-1951). The classic example: The Attentional view • This view assumes that what we actually express reflects which parts of an event attract our attention. • A main concept of this approach is Fillmore’s (1975) notion of ‘frame’, i.e. an assemblage of the knowledge we have about a certain situation. – Depending on our cognitive ability to direct our attention, different aspects of this frame are highlighted, resulting in different linguistic expressions (Talmy 1988, 1991, and 1996). The Tenets to Follow in Cognitive Linguistics – The design features of languages, and our ability to learn and use them are accounted for by general cognitive abilities, kinaesthetic abilities, our visual and sensimotor skills and our human categorisation strategies, together with our cultural, contextual and functional parameters (Barcelona 1997: 8). • The Modularity Hypothesis (cf. Chomsky 1986; Fodor 1983) – The ability to learn one’s mother language as a unique faculty, as a special innate mental module – Language is understood as a product of general cognitive abilities. Embodiment as the most fundamental tenet in the Modularity Hypothesis • According to Johnson 1987; Lakoff 1987; Lakoff and Johnson 1980, 1999 – Mental and linguistic categories are not abstract, disembodied and human independent categories – We create them on the basis of our concrete experiences and under the constraints imposed by our bodies. Three levels - the ‘embodiment of concepts’ (Lakoff and Johnson, 1999) • The ‘phenomenological level’ – “consists of everything we can be aware of, especially our own mental states, our bodies, our environment, and our physical and social interactions” (1999: 103). • This is the level at which one can speak about the feel of experience, the distinctive qualities of experiences, and the way in which things appear to us. Three levels - the ‘embodiment of concepts’ (Lakoff and Johnson, 1999) • The ‘neural embodiment’ – deals with structures that define concepts and operations at the neural level • The ‘cognitive unconscious’ – concerns all mental operations that structure and make possible all conscious experience It is only by the descriptions and explanations at these three levels that one can achieve a full understanding of the mind. The theory of linguistic meaning • For Cognitive Linguistics, meanings do not exist independently from the people that create and use them (Reddy 1993). – All linguistic forms do not have inherent form in themselves, they act as clues activating the meanings that reside in our minds and brains. – This activation of meaning is not necessarily entirely the same in every person, • because meaning is based on individual experience as well as collective experience (Barcelona 1997: 9). Thus, according to cognitive linguists, • we have no access to a reality independent of human categorisation, and that is why the structure of reality as reflected in language is a product of the human mind. • Semantic structure reflects the mental categories which people have formed from their experience and understanding of the world. • Methodological Principles • Human categorisation is one of the major issues in Linguistics. • The ability to categorise, i.e., to judge that a particular thing is or is not an instance of a particular category, is an essential part of cognition. • Categorisation is often automatic and unconscious, except in problematic cases. – This can cause us to make mistakes and make us think that our categories are categories of things, when in fact they are categories of abstract entities. • When experience is used to guide the interpretation of a new experience, the ability to categorise becomes indispensable. • How human beings establish different categories of elements has been discussed ever since Aristotle. The Three Scales of Diachrony (Wang, 1978) • The microhistory of language – Is reckoned across a very thin slice of time, in years or decades. • The mesohistory of language – deals with the middle time scale.. A classic question in language mesohistory has been the manner or means by which a change is implemented. • The macrohistry of language – In considering language change within the largest time perspective The Cognitive Basis of Language: Language and Thought (Dirven, R. & Verspoor, M. 1998). Some fundamental aspects of language and linguistics • Semiotics - the systematic study of signs which analyzes verbal and non-verbal systems of human communication as well as animal communication. • Semiotics distinguishes between three types of signs: – indices – icons – symbols • They represent three different structural principles relating form and content. • Linguistic categories not only enable us to communicate, but also impose a certain way of understanding the world. What is a sign? • In its widest sense, a sign may be defined as a form which stands for something else, which we understand as its meaning. • Different types of signs in sign systems – raising our eyebrows -> indexical – drawing the outline of a woman by using our hands -> iconic – expressing our thoughts by speaking -> symbolic • All these methods of expression are meaningful to us as “signs” of something. An indexical sign/index • An indexical sign/index (meaning ‘pointing finger’ in Latin) - points to something in its immediate vicinity • e.g. – a signpost for traffic pointing in the direction of the next town – facial expressions – raising one’s eyebrows or furrowing one’s brows – “point” to a person’s internal emotional states of surprise or anger. An iconic sign/icon • • • An iconic sign/icon, (from Greek eikon ‘replica’) provides a visual, auditory or any other perceptual image of the thing it stands for. is similar to the thing it represents. e.g. Temporary Conditions Warning Signs Information and Direction Signs • • These images are only vaguely similar to reality but their general meanings are very clear. The gestural drawing of something (e.g., a woman’s shape with one’s hands) with one’s finger is an iconic sign. A symbolic sign/symbol • does not have a natural link between the form and the thing represented, • only has a conventional link. e.g. • the traffic sign of an inverted triangle: – does not have a natural link between its form and its meaning “give right of way.” – the link between its form and meaning is purely conventional. • signs for money –£ $ military emblem flag Most of language has no natural link at all between the word form and its meaning. “symbolic” used in linguistics • understood in the sense that, by general consent, people have “agreed” upon the pairing of a particular form with a particular meaning A hierarchy of abstraction amongst the three types of signs Indexical signs • “primitive” and the most limited signs – restricted to “here” and “now” • very wide-spread in human communication – e.g., in body language, traffic and advertising Iconic signs • more complex – their understanding requires the recognition of similarity. – The iconic link of similarity needs to be consciously established by the observer. • may be fairly similar as with icons or may be fairly abstract – e.g. pictures of men and women on toilet doors, cars or planes in road signs. • probably not found in the animal kingdom. Symbolic signs • The exclusive prerogative of humans. • Humans have more communicative needs than pointing to things and replicating things • Humans want to talk about things which are more abstract in nature • The most elaborate system of symbolic signs is natural language in all its forms – A spoken language as the most universal form – a written form of language develops due to civilization and intellectual development – a sign language largely based on conventionalized links between gestures and meanings. The three types of signs are illustrated in Table 1 and reflect general principles of coping with forms and meanings. Principles of indexicality, iconicity and symbolicity • Indexical signs reflect a more general principle, whereby things that are contiguous can stand for each other. • Iconic signs reflect the more general principle of using an image for the real thing. • Symbolic signs allow the human mind to go beyond the limitations of contiguity and similarity and establish symbolic links between any form and any meaning. Structuring Principles in language • Principle of indexicality in language • The principle of indexicality in language means that we can “point” to things in our scope of attention. • We consider ourselves to be at the centre of the universe – everything around us is seen from our point of view. • e.g. – The ego-centric view shown in language – Deictic expressions: here, there, now, then, today, tomorrow, this, that, come, go, etc. – relate to the speaking EGO, who imposes his perspective on the world. – depend for their interpretation on the situation in which they are used. • The EGO serves as the “deictic centre” for locating things in space. • The EGO serves as the “deictic centre” for locating things with respect to other things as well. • e.g. – the bicycle and tree example – deictic orientation changes – the car and bicycle examples – inherent orientation stays constant Anthropocentric perspective – a more general level led by human psychological proximity • Our anthropocentric perspective of the world follows from the fact that we are foremost interested in humans like ourselves. • We human beings always occupy a privileged position in the description of events. • e.g. – A human subject is very often used in expressing events and states. • She knows the poem by heart. • *The poem is known by heart by her. – Personal pronouns for males and females as opposed to it – Special interrogative and relative pronouns referring to humans as opposed to things – A special possessive form for human (the man’s coat but not * the house’s roof) The principle of iconicity in language • The principle of iconicity in language means that we conceive a similarity between a form of language and the thing it stands for. • Three sub-principles: – the principle of sequential order • a phenomenon of both temporal events and the linear arrangement of elements in a linguistic construction. – the principle of iconicity determines the order of two or more clauses. • Julius Caesar’s historic words: veni, vidi, vici ‘I came, I saw, I conquered’ – the principle of iconicity also determines the sequential order of the elements in “binary” expressions which reflect temporal succession: e.g. now and then, now and never, sooner or later, day and night – cause and effect, hit and run, trial and error, give and take, wait and see, pick and mix, cash and carry, park and ride • a possible word order of subject, verb and object in a sentence in a language: – SVO, SOV, VSO, OSV, OVS, VOS The principle of distance • accounts for the fact that things which belong together conceptually tend to be put together linguistically • things that do not belong to together are put in a distance • e.g. types of subordinate clause: – I made her leave – I wanted her to leave – I hoped that she would leave. The iconic principle of quantity • accounts for our tendency to associated more form with more meaning e.g. No smoking. Don’t smoke, will you? …… The principle of symbolicity in language • Refers to the conventional pairing of form and meaning as is typically found in the word stock of a language. • The link between the form and the meaning of symbolic signs was called arbitrary (Saussure 1916) • However, the whole range of new words or new senses of existing words are motivated. Linguistic and conceptual categories Conceptual categories • Such concepts which slice reality into relevant units are called categories. • Conceptual categories are concepts of a set as a whole. • Languages only covers part of the world of concepts which human have or may have. • The notion of concept may be understood as “a person’s idea of what something in the world is like’. • The world is not some kind of objective reality existing in and for itself but is always shaped by our categorizing activity. • Conceptual categories which are laid down in a language are linguistic categories, or linguistic signs. • The human conceptualizer, conceptual categories and linguistic signs are interlinked (see Table 2 on page 15) Lexical categories • Lexical categories are defined by their specific content, while grammatical categories provide the structural framework for the lexical material. • The conceptual content of a lexical category tends to cover a wide range of instances. • The best member, the prototypical member, the most prominent member of a category, is the subtype that first comes to mind when we think of that category. • Alongside prototypical members of a category and less prototypical ones, we also hve more peripheral or marginal members. Grammatical categories • The structural framework provided by grammatical categories include abstract distinctions which are made by means of word classes, number, tense, etc. • Most of the words classes were first introduced and defined by Greek and Roman grammarians as partes orationis ‘parts of speech’. • The meanings traditionally associated with word classes only apply to prototypical members. • Prototypical nouns denote time-stable phenomena, while verbs, adjectives and adverbs denote more temporary phenomena. Linguistics Value (Saussure) • Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) - He is universally regarded as ‘the father of structuralism.’ His structural study of language emphasizes the arbitrary relationship of the linguistic sign to that which it signifies. Saussure distinguished synchronic linguistics (studying language at a given moment) from diachronic linguistics (studying the changing state of a language over time); he further opposed what he named langue (the state of a language at a certain time) to parole (the speech of an individual). Saussure's most influential work is the Course in General Linguistics (1916), a compilation of notes on his lectures. Saussure’s general view about linguistics and language • There is a distinction between language (langue) and the activity of speaking (parole). • Speaking is an activity of the individual; language is the social manifestation of speech. • Language is a system of signs that evolves from the activity of speech. • language is a borderland between thought and sound, where thought and sound combine to provide communication. • A linguistic sign is a combination of a concept and a sound-image. • The concept is what is signified, and the sound-image is the signifier. The combination of the signifier and the signified is arbitrary; i.e., any sound-image can conceivably be used to signify a particular concept. Saussure’s general view about linguistics and language –cont’d • Nothing enters written language without having been tested in spoken language. • The units of language can have a synchronic or diachronic arrangement. • The meaning or signification of signs is established by their relation to each other. • The relation of signs to each other forms the structure of language. • Synchronic reality is found in the structure of language at a given point in time. • Diachronic reality is found in changes of language over a period of time. • Language has an inner duality, which is manifested by the interaction of the synchronic and diachronic, the syntagmatic and associative, the signifier and signified. (Scott, 2001)