Rethinking the Subject: Feminism and Creative Practice

advertisement

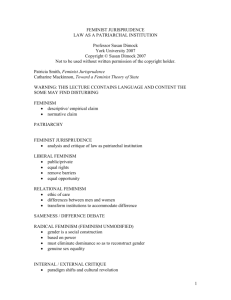

Rethinking the Subject: Feminism and Creative Practice LECTURE ONE Why Feminism? (What of Feminism?) Alexandra Kokoli a.m.kokoli@rgu.ac.uk Lecture Overview • What is (second-wave) feminism? • What has been/is the relationship between feminism and creative practice? – Areas and types of intervention • Feminism & psychoanalysis – The gaze – Fetishism • Feminism and/against art history WACK! Art & the Feminist Revolution (Los Angeles, MoCA, Connie Butler, curator) • • • • ‘My ambition for “Wack!” is to make the case that feminism’s impact on art of the 1970s constitutes the most influential international “movement” of any during the postwar period – in spite or perhaps because of the fact that it seldom cohered, formally or critically, into a movement the way Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism, or even Fluxus did.’ (p. 15) Feminism = ‘an ideology of shifting criteria’ (ibid.) Not defined by a few charismatic individuals Open-ended Subject to constant self-evaluation and critique Political or militant? • Too diverse; C. Butler: not coherent enough • E.g. WACK! included artists who didn’t identify as feminists! • Redefining the limits of ‘the political’ (‘the personal is political’) • ‘art practice with no overt political content may, nevertheless, be able to sensitize us politically’ [Susan Hiller, ‘Anthropology into Art: SH interviewed by Sarah Kent and Jacqueline Morreau’, in Women’s Images of Men (London: Pandora, 1990), p. 151] Griselda Pollock “The Politics of Theory: Generations and Geographies in Feminist Theory and the Histories of Art Histories” ‘[F]eminism signifies a set of positions, not an essence; a critical practice not a doxa [= commonly held opinion]; a dynamic selfcritical response and intervention not a platform. It is the precarious product of a paradox. Seeming to speak in the name of women, feminist analysis perpetually deconstructs the very terms around which it is politically organised.’ (p. 5) Feminism(s)? A belief (based on experience and/or analysis) that women in society are systemically disadvantaged and actively discriminated against because of their gender, combined with the commitment to challenge (through critique) and overthrow (through activism) the conditions that legitimate such discrimination, as well as the discrimination itself. • Education • Employment • Control over one’s own body (fertility; selfdetermination) Sandra Kemp and Judith Squires (eds.), Feminisms, series: Oxford Readers (Oxford: OUP, 1997) Second-wave feminism(s) (late 1960s to mid 1980s) • Origins: – women’s movements & consciousness-raising groups (rape & domestic abuse crisis centres, ecology) – Marxism (mostly UK & Europe) – Civil rights movements (mostly US) • Present & future: – Intellectual and artistic legacies/ feminism in the academy – Professionalisation of feminism? – ‘Turn to culture’ (Michele Barrett) in 1980s-90s, followed by a re-turn to grassroots feminism (e.g. online blogs and publications; http://europeanfeministforum.org/ , etc.)? Equality vs. Difference EQUALITY • ‘Liberal feminism’ • Like the suffragettes? • Aim then: equal rights and access • Aim now: women in positions of power (~ US popular feminisms) DIFFERENCE • ‘French feminisms’ • Focus on the psychosocial construction of femininity • Engagement with psychoanalysis • Marxist too (UK & Fra) • More radical (in theory!) • More intellectual Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (1949) trans. H. M. Parshley (London: Vintage, 1997) ‘One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman. No biological, psychological, or economic fate determines the figure that the human female presents in society; it is civilization as a whole that produces this creature, intermediate between male and eunuch, which is described as feminine.’ (p. 295; beginning of the chapter ‘Childhood’) Why ‘subject’? • In the grammatical sense • It is through and in language that we are • Jacques Lacan (post-structuralist Freudian): we do not own/inhabit language, it owns us! • Thus, we are subjected to the Symbolic (= the sphere of signifiers, i.e. carriers of meaning designated by convention) • Subjected to and shaped by culture in general The troubled marriage of FEMINISM & PSYCHOANALYSIS • Freud on femininity: proscription or description? – Woman as ‘castrated’; ‘penis envy’ – Hysteria as a gendered mental disorder – Femininity described in unfavourable terms: prone to jealousy; poor creative impulse (procreative instead); poor moral faculties – Lacan: ‘castration’ purely symbolic – the recognition of difference • Juliet Mitchell: not only description but analysis • Jane Gallop: may be interpreted against the grain • Jacqueline Rose (in ref. to hysteria case studies): not just analysis, but admission of how complex, difficult and often unpleasant it is to take one’s position in the binary sexual economy See the brilliant Jacques Lacan: A feminist introduction by Elizabeth Grosz Feminism and Visual Culture • Critique of popular visual culture (cinema, advertising) – Psychoanalytic and Marxist models and terms of analysis – The (gendered) gaze; fetishism • Critique of art (& design) history and their methods (the canon, etc.) – – – – Why have there been no great women artists? (Linda Nochlin) ‘firing the canon’ (Griselda Pollock) Pollock and Parker, Old Mistresses (1981) Challenging the ‘modernist myth’ (R. Krauss) of originality • Creative practice as critique – See next lecture! • All three connected, in theory (same principles) and practice (same people involved) [CRITIQUE = not the same as criticism, though usually critical; detailed analysis that aims to uncover the internal logic of the text/object in question, as well as examine the text/object itself] A different popular visual culture (?!) Triumph Underwear, 1960s ‘Undies to be searched in.’ ‘Don’t scoff. In five minutes time you could get mistaken for a Secret Service courier. Handsome Colonel Fernandez, the infamous Transylvanian double agent, would search you thoroughly for the microfilm. Blushmaking? Not if you are in Triumph undies. Get in some quick.’ Laura Mulvey, ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ (1975), in Visual and Other Pleasures (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 1989), pp. 14-26 Mulvey: film-maker, curator, theorist, and academic (Birkbeck College) • For a political use of psychoanalysis (in the feminist and broader sense) • Influence of Bertolt Brecht: pleasure supports the illusion of spectacle and thus the ideology of representation • ‘Displeasure’ as a politically justified aesthetic choice – E.g. Mulvey and Peter Wollen’s film Riddles of the Sphinx (1977) ‘The daily life of a woman with a child. […] I have seen many experimental and "art" films but during this film I became so bored that after about 45 minutes and more than half the viewing audience had left I finally got up and walked out also. I don't recommend this movie unless you need a place to take a nap.’ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0076625/ Ideology • Set of beliefs, values and opinions that shapes the way we think, act, and make sense of the world, ourselves and our position in it. • ‘We’ = no such think as a personal ideology. About social groups and communities. Traditionally, about ‘class’, but also gender, ethnicity, etc. Sometimes, ideology is the very process by which we identify ourselves as part of a particular group. • ~ Misrecognition of the economic system and of identity. Marx: ‘false consciousness’ = a screen separating us from the world and through which we perceive the world; false because it doesn’t allow us to recognise our actual position in the production process, i.e. that the labour of working class produces surplus value and perpetuates capitalism (i.e. complicit in their own subordination). • Judith Williamson, Decoding Advertisements (1978): ideology no longer about our position in the process of production, but about identification with a made-up group through what we chose to consume. Hence, the ‘Pepsi people’; the Specsaver’s people (and those who fail to qualify). The Gaze (Lacan; Mulvey) • Not the same as looking but point of view (not optics but perspective) – the blind are implicated too! (cf. Sartre) • Connected to mastery & drawing boundaries between self and other • Male gaze: a gendered fantasy of coherence between – Knowledge – Power – Pleasure Grounded on: – an ‘active/passive heterosexual division of labour’ • Scopophilia: the mutual implication of the attraction exercised by narrative film on the one hand, and the pleasure that heterosexual men take in looking at beautiful women on the other – the culture industry and patriarchy in cahoots Fetishism • Fetishism = 1. the psychosocial mechanisms of objectification; 2. the privileging of belief over knowledge (Mulvey) (At least) 3 kinds: • Freudian: the substitution of the Mother’s missing Phallus with something else – ultimately, the disavowal of sexual difference (cf. Beauvoir: woman = eunuch). Feminine beauty makes up for (& covers up) female inadequacies • Marxist: commodity fetishism bestows an apparently innate value on a commodity, while disavowing the real source of its value that is labour power. Fetishism obscures class relations. • Anthropological: the bestowal to an object of qualities and powers that are not supported by (or even connected to) its use (William Pietz) Deadly combos – e.g. cinema (window to the world; pretty ladies; we are the hero for 90 mins because we share his point of view) Mulvey, Fetishism and Curiosity (London: BFI, 1996) Fetishism provided the “alchemical link” between Marx and Freud, the two main thinkers with whom the Left and, subsequently, feminism negotiated its analytical tools. In both Marx and Freud, fetishism is called on to explain a blockage “or phobic inability” “in the social or sexual psyche” Instances of fetishism: symptomatic of blindspots and thus flag them as troubled and potentially vulnerable areas, where ideology is more likely to become unstuck (pp. 1-2) Linda NOCHLIN Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? (1971) • What/who is ‘great’? – The modernist cult of originality (cf. Old Mistresses) – The gender bias of ‘genius’ (ibid.) • Women art students historically led towards minor genres of painting, such as portraiture, landscape and still life • Female students of painting banned from attending life drawing sessions as late as the 1890s, to protect their virtue! – Life drawing = prerequisite for history painting, thus women confined to the ‘minor’ genres Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1652), L: Susanna and the Elders (1610) R: Judith Decapitating Holofernes (c. 1618) Tintoretto, Susanna and the Elders (1555-6) Gentileschi, La Pittura (Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting, 1630s) Artemisia Gentileschi: A Feminist Heroine (?) • Tragic life story (see Kahlo too) • English translation of the trial transcripts in Mary D. Garrard, Artemisia Gentileschi : the image of the female hero in Italian baroque art (Princeton University Press, 1989) • Griselda Pollock, ‘The female hero and the making of a feminist canon: A G’s representations of Susanna and Judith’, ch. 5 of Differencing the Canon, pp. 97-127: on the dangers of biographism for women artists What are SEMINARS for? • Asking questions (from lectures, readings, etc.) – Two sets of readings & and little overlap between lectures and readings – connections need to be forged – Do (SOME) reading – Be specific: there are no stupid questions but there are lazy ones • Testing out your ideas • Starting to build your NOTEBOOK through SEMINAR TASKS • NB: Seminars start tomorrow, Tuesday 12th February (9.30am, 10.30am, 12 noon) Seminar Task (1) Keeping in mind Griselda Pollock’s definition of feminism as critique rather than doxa, select ONE WORK by any artist or designer (not necessarily contemporary; not necessarily female) and be prepared to discuss it in class in reference to feminist critical and/or creative practice. For inclusion in the NOTEBOOK!