NOTES ON DAVIES, chapter 3

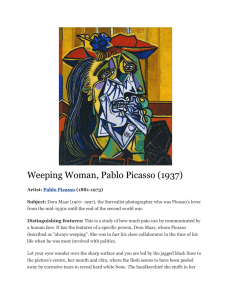

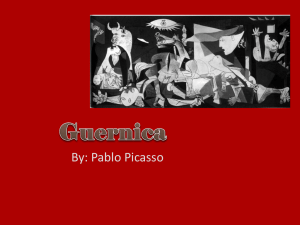

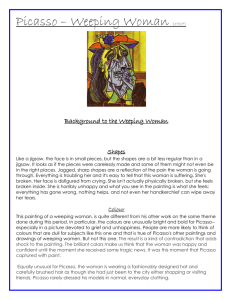

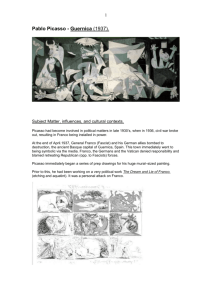

advertisement

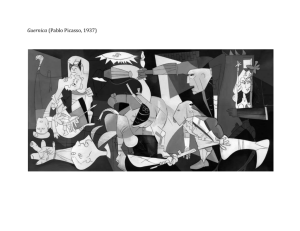

PHILOSOPHY 105 (STOLZE) Notes on Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) Self-Portrait (1906) Picasso’s Three Challenges to Art • History • Beauty • Resemblance (See Simon Schama, The Power of Art [New York: HarperCollins, 2006], especially pp. 355-61.) Boy Leading a Horse (1905-6) Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907) Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (1910) Seated Bather (1930) The Dream (1932) The Bullfight: Death of the Toreador (1933) Minotauromachy (1935) Dreams and Lies of Franco, 1st Series (1937) An Analysis of Dreams and Lies of Franco Picasso made two prints in this format—three rows of three scenes— beginning January 8, 1937, that together form an eighteen-scene narrative. This print is the first of the two. In the upper right, the Fascist general Franco is depicted as a grinning monstrous figure, devouring the innards of his own horse, which he has just killed; the next two scenes show the results of battle; and in the next two, Franco is in combat with an angry bull, symbolizing Spain. The last four scenes were added on June 7; meanwhile, the Basque town of Guernica was leveled by bombs, and Picasso painted his famous mural protesting that atrocity. Three of the last four scenes of this print relate to his studies for that painting. Guernica (1937) Simon Schama on Guernica “It’s just paint and canvas, just black and white paint, but it somehow has authority and endurance: unbombable, indestructible. And it achieves another miracle for, despite the glut of images of 20th-century massacre, this one somehow manages, still, to get under the skin. This is what all great art should do: crash into our lazy routines. Guernica fights the truly deadly habit, a sickness of our own time as well as of his, of taking violent evil in our stride, of yawning at the video-massacre: seen it before; go away; don’t spoil the fun of art. Guernica wasn’t made for fun. It was made to rip away the scar tissue, rob us of our sleep. It did. So in every way that mattered Picasso had won, art had won, humanity had won.” (Excerpted from Simon Schama, The Power of Art [New York: HarperCollins, 2006], p. 388.) The Weeping Woman (1937) Questions about The Weeping Woman • • • • • • What is she holding? Why is her face painted with these colors? Why is her face disfigured? But real people don’t look like this! Why paint a picture that viewers will find “ugly”? Could Picasso have painted a “Weeping Man”? An Analysis of The Weeping Woman The Weeping Woman series is regarded as a thematic continuation of the tragedy depicted in Picasso's epic painting Guernica. In focusing on the image of a woman crying, the artist was no longer painting the effects of the Spanish Civil War directly, but rather referring to a singular universal image of suffering. The model for the painting, indeed for the entire series, was Dora Maar, who was working as a professional photographer when Picasso met her in 1936; she was the only photographer allowed to document the successive stages of Guernica while Picasso painted it in 1937. Dora Maar was Picasso's mistress from 1936 until 1944. In the course of their relationship Picasso painted her in a number of guises, some realistic, some benign, others tortured or threatening. Picasso explained: "For me she's the weeping woman. For years I've painted her in tortured forms, not through sadism, and not with pleasure, either; just obeying a vision that forced itself on me. It was the deep reality, not the superficial one." "Dora, for me, was always a weeping woman....And it's important, because women are suffering machines." Weeping Woman with Handkerchief (1937) An Analysis of Weeping Woman with Handkerchief In Weeping Woman with Handkerchief shows a woman who is in deep sorrow. One hand is at her heart while tears come streaming down her face. Her head is covered with traditional Spanish head covering called a mantilla. This represents the ideals of Spanish womanhood. We can see a line down the center of her face which is a technique developed by Picasso to show different angles or perspectives of an object or person. It is intended to depict the front and the profile of the person at the same time. The Charnel House (1945) An Analysis of The Charnel House “The Charnel House was Picasso’s most overtly political painting since Guernica of 1937 (now in the Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid). Echoing Guernica in its pyramidal composition and abstracted forms, it was inspired by newspaper war photographs, the tones of which are reflected in its somber black–and–white palette. The central jumble of figures—a murdered family sprawled beneath a dining table—might suggest the piles of corpses discovered in Nazi concentration camps upon their liberation. While Guernica, a commentary on the Spanish Civil War, may be seen as signaling the violent beginning of World War II, The Charnel House marks its horrific end.” (From http://www.moma.org/collection/object.php?object_id=78752)