William Dawes: The Forgotten Midnight Rider

advertisement

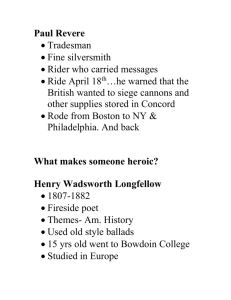

William Dawes: The Forgotten Midnight Rider Posted on February 17, 2014 by Rebecca Beatrice Brooks William Dawes was a Boston tanner and one of the riders sent by Dr. Joseph Warren to alert John Hancock and Samuel Adams of the approaching British army on the night of April 18th, 1775. The following are some facts about William Dawes: Dawes was born in Boston on April 6, 1745. He was the second of twelve children born to William Dawes and Lydia Boone. Dawes married twice, first to Mehitable May, who died in October of 1793, and then to Lydia Gendall. On October 28, 1767, Dawes was one of 650 Boston citizens who signed a “nonimportation agreement,” promising not to buy goods imported from Britain, which included furniture, clothes, nails, anchors, gauze, shoe leather, malt liquors, loaf sugar, starch and glue. To further support this cause, the Boston Gazette states that Dawes also wore a suite made entirely in America on his wedding day. In April of 1768, Dawes joined the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company, a private training organization for militia officers, and was also promoted to second major of the regiment of the Boston militia. Dawes was also a member of the patriotic group the Sons of Liberty and was a Freemason, although it is not clear which Boston lodge he belonged to. William Dawes, oil painting by John Johnston, circa 1785-95 According to the book “History of the Military Company of the Massachusetts,” as an ardent patriot, Dawes often rode throughout the colony trying to find recruits for the colonial cause: “He scoured the country, organizing and aiding in the birth of the Revolution. His granddaughter wrote: ‘During these rides, he sometimes borrowed a friendly miller’s hat and clothes and sometimes he borrowed a dress of a farmer, and had a bag of meal behind his back on the horse. At one such time a British soldier tried to take away his meal, but grandfather presented arms and rushed on. The meal was for his family. But in trying to stir up recruits, he was often in danger.’” In October of 1774, Dawes planned and led a daring break-in at the gun house on Boston Common. While the guards were at roll call, Dawes and several members of his artillery company stole two small brass cannons, sneaking them out the back window, and hid them in a large box under the desk in a nearby school house. When a British sergeant later discovered the cannons were missing, he exclaimed: “They are gone. These fellows will steal the teeth out of your head while you are keeping guard.” The guards searched the yard, gun-house and school house but never found the hidden cannons. The cannons remained hidden in the school house for two weeks until Dawes had them removed one night in a wheelbarrow and hid them under a pile of coal in a blacksmith shop. On January 5, 1775, the Committee of Safety voted to move the stolen cannons to Waltham. The cannons remained in active service throughout the revolutionary war. Dawes also injured his arm during the break-in and was attended to by fellow patriot Dr. Joseph Warren but, due to the illegal nature of the event, Dawes thought it best not to tell Warren how the injury happened. It was Warren who later sent both Dawes and Paul Revere on their famous midnight ride on April 18th, according to the book “History of the Military Company of the Massachusetts: “For some days before the 19th of April, 1775, it had been known the British were preparing to move. It was suspected that the destination of the troops would be Concord, where stores of war material were gathered, and in the vicinity of which were Hancock, Adams and other Revolutionary leaders. On the afternoon of the day before the attack, Gen. Warren learned that the British were about to start. He waited until they had begun to move their boats, and then sent out William Dawes, Jr, by the land route, over the [Boston] neck, and across the river at the Brighton Bridge to Cambridge and Lexington; and directly after, ‘about ten o’clock,’ he ‘sent in great haste’ for Paul Revere, and sent him by the water route through Charlestown to Lexington to arouse the country, and warn Hancock and Adams.” Revere and Dawes took different routes during their rides. Revere crossed the Charles river by boat and rode from Charlestown through Somerville, Medford, Arlington and Lexington. Dawes traveled a longer distance than Revere, going south across Boston neck to Roxbury, then west and north through Brookline, Brighton, Cambridge and Lexington, covering a total of 17 miles in three hours. Dawes’ route also required passing through a guarded gate at Boston neck, which was on high alert at the time, according to the History Channel website: “Dawes set off around 9 p.m., about an hour before Warren dispatched Revere on his mission. Within minutes, he was at the British guardhouse on Boston Neck, which was on high alert. According to some accounts, Dawes eluded the guards by slipping through with some British soldiers or attaching himself to another party. Other accounts say he pretended to be a bumbling drunken farmer. The simplest explanation is that he was already friendly with the sentries, who let him pass. However Dawes did it, he made it in the nick of time. Shortly after he passed through the guardhouse, the British halted all travel out of Boston.” Unlike Revere, Dawes didn’t stop to alert colonial minutemen during his ride and instead rode straight on to Lexington. It’s not clear why Dawes did this but it is possible that he believed his mission was only to alert John Hancock and Samuel Adams of the approaching British army. As a result, the militia took longer to respond to the British army’s approach on Dawes route than on Revere’s. Dawes finally met up with Revere at the Hancock-Clarke house in Lexington, where Hancock and Adams were staying, around 12:30 am. After warning Hancock and Adams of the approaching army, Revere and Dawes mounted their horses again and set off for Concord, running into Dr. Samuel Prescott along the way. Hancock-Clarke House, Lexington, Mass, in 2014. Photo Credit: Rebecca Brooks Prescott decided to join them on their trip but the three riders soon encountered a British patrol around 3 a.m. According to Revere’s account of the ride, Dawes and Prescott managed to get away but Revere was captured: “After I had been there [at the Hancock-Clarke house] about half an hour, Mr. Dawes came; after we refreshed our selves, we and set off for Concord, to secure the stores, &c. there. We were overtaken by a young Doctor Prescott, whom we found to be a high Son of Liberty. I told them of the ten officers that Mr. Devens met, and that it was probable we might be stopped before we got to Concord; for I supposed that after night, they divided them selves, and that two of them had fixed themselves in such passages as were most likely to stop any intelligence going to Concord. I likewise mentioned, that we had better alarm all the inhabitants till we got to Concord; the young Doctor much approved of it, and said, he would stop with either of us, for the people between that & Concord knew him, & would give the more credit to what we said. We had got nearly half way. Mr Dawes & the Doctor stopped to alarm the people of a house: I was about one hundred rod a head, when I saw two men, in nearly the same situation as those officer were, near Charlestown. I called for the Doctor & Dawes to come up; – were two & we would have them in an Instant I was surrounded by four; – they had placed themselves in a straight road, that inclined each way; they had taken down a pair of bars on the North side of the road, & two of them were under a tree in the pasture. The Doctor being foremost, he came up;and we tried to get past them; but they being armed with pistols & swords, they forced us in to the pasture; – the Doctor jumped his horse over a low stone wall, and got to Concord.” Dawes, tried to outrun the patrol but knowing his horse was too tired, he scared off the two soldiers chasing him by riding up to a nearby farm house and shouting “Halloo, boys, I’ve got two of ‘em!” The soldiers feared it was an ambush and rode away. Unfortunately, Dawes had halted his horse so suddenly that he was bucked off it. His whereabouts for the rest of the night are unknown. Dawes reportedly later joined the Continental army in Cambridge and some sources state he fought at the Battle of Bunker Hill in June, 1775. He also moved his family to Worcester, sometime during the ongoing Siege of Boston, where he was later appointed commissary. According to the book “History of the Military Company of the Massachusetts” when a group of captured British and Hessian soldiers that had been looting Worcester along their march were brought to Dawes for their daily rations, Dawes deliberately shortchanged them out of revenge: “The Germans stole and robbed houses, as they came along, of clothing and everything on which they could lay their hands to a large amount. When at Worcester, indeed, they themselves were robbed, though in another way. One Dawes, the issuing commissary, upon the first company coming to draw their rations, balanced the scales by putting into that which contained the weight of a large stone. When that company was gone (unobserved by the Germans, but not by all present), the stone was taken away before the next came: and all the other companies except the first had short allowance.” Illustration of Paul Revere’s ride published in “Paul Revere’s Ride” by Longfellow circa 1905 Despite the fact that Dawes played a pivotal role in the midnight ride of April 18th, 1775, he has been almost entirely forgotten by historians and completely overshadowed by Paul Revere. One reason is because Revere wrote a personal account of his ride, which has been widely circulated, yet very few records exist of Dawes’ participation in the ride. Another reason is because of the publication of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere” in 1861, which wrote Dawes and Prescott out of the event entirely. In an attempt to remedy this, Century Magazine published a parody of the poem, titled “The Midnight Ride of William Dawes” by Helen F. Moore, in 1896: I am a wandering, bitter shade, Never of me was a hero made; Poets have never sung my praise, Nobody crowned my brow with bays; And if you ask me the fatal cause, I answer only, “My name was Dawes” ‘Tis all very well for the children to hear Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere; But why should my name be quite forgot, Who rode as boldly and well, God wot? Why should I ask? The reason is clear — My name was Dawes and his Revere. When the lights from the old North Church flashed out, Paul Revere was waiting about, But I was already on my way. The shadows of night fell cold and gray As I rode, with never a break or a pause; But what was the use, when my name was Dawes! History rings with his silvery name; Closed to me are the portals of fame. Had he been Dawes and I Revere, No one had heard of him, I fear. No one has heard of me because He was Revere and I was Dawes. Sadly, not only have historians forgotten about Dawes but even some of his own peers forgot his name, according to an article on the History Channel website: “Contemporaries couldn’t even recall his [Dawes] name. William Munroe, who had stood guard at the Hancock-Clarke House, later reported that Revere arrived along with a ‘Mr. Lincoln.’ In a centennial commemoration, Harper’s Magazine called Dawes ‘Ebenezer Dorr.’” Dawes died on February 25, 1799. Even the real location of his grave has been forgotten. For years it was believed that Dawes was buried in King’s Chapel Burying ground, where he has a headstone. Yet, in 2007, it was discovered that Dawes might be buried in his wife’s family plot in Forest Hills Cemetery instead.