Research Misconduct - Program for Disability Research

advertisement

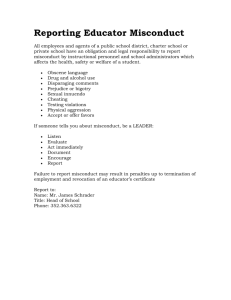

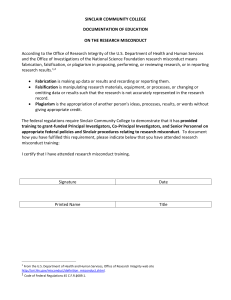

The Responsible Conduct of Research: Research Misconduct Claudia Farber Assistant Dean Graduate School New Brunswick September, 2009 Video vignettes & ORI 1st video behavioral science – research misconduct – 1st video http://www.citiprogram.org/ Syracuse U. videos, #1, 2, 11 http://gradschpdprograms.syr.edu/resources/videos.php ORI Website Objectives • Why study the Responsible Conduct of Research? • Brief historical review • Define “Research Misconduct” & “Questionable Research Practices” • Review Rutgers Academic Integrity Policy • Identify issues surrounding research misconduct • Develop techniques to resolve problems • Breakout groups & discussion of case studies Why study RCR? 1. Mandated – 1989: NIH Training Grant Requirement Office of Scientific Integrity (OSI/ORI) established for policy, oversight, and investigation of misconduct – 2000: NIH requirement: protection of research subjects – 2007: America COMPETES Act mandates RCR training – Aug. 2009: NSF Regulations: “each institution that applies for financial assistance from [NSF]describe in its grant proposal a plan to provide appropriate training and oversight in the responsible and ethical conduct of research to undergraduate students, graduate students, and postdoctoral researchers participating in the proposed research project.” Why study RCR? con’t 2. New structural forces “Increasing complexity and competitiveness in research environments, the prevalence of interdisciplinary and international involvement in research projects, and the close coupling of commerce and academia have created an ethically challenging environment for young scientists and engineers.“ (Hollander, 2009) 3. Maintain public support for research & trust in the results – Undermined by prominent cases: Tuskegee syphilis study; Milgram’s studies on inflicting pain; recent news reports, e.g., falsifying of stem cell data; withholding data on cell phone driving risks; ghostwriting of drug company studies by academics; etc. 4. RCR is the right thing In response… – Most research universities require training in RCR typically online training (e.g., CITI) supplemented by workshops – Proliferation of conferences, workshops, publications, online resources, etc. from the Council of Graduate Schools, the National Academies, AAAS, NIH/NSF et al. the right thing “The scientific enterprise is built on a foundation of trust. Society trusts that scientific research results are an honest and accurate reflection of a researcher’s work. Researchers equally trust that their colleagues have gathered data carefully, have used appropriate analytic and statistical techniques, have reported their results accurately, and have treated the work of other researchers with respect. When this trust is misplaced and the professional standards of science are violated, researchers are not just personally affronted—they feel that the base of their profession has been undermined. This would impact the relationship between science and society.” (National Academy of Science, 2009) and… “In general terms, responsible conduct in research is simply good citizenship applied to professional life. Researchers who report their work honestly, accurately, efficiently, and objectively are on the right road when it comes to responsible conduct. Anyone who is dishonest, knowingly reports inaccurate results, wastes funds, or allows personal bias to influence scientific findings is not. However, the specifics of good citizenship in research can be a challenge to understand and put into practice. Research is not an organized profession in the same way as law or medicine. Researchers learn best practices in a number of ways and in different settings. The norms for responsible conduct can vary from field to field. Add to this the growing body of local, state, and Federal regulations and you have a situation that can test the professional savvy of any researcher.” (Steneck, 2007) Federal Definition Research misconduct is defined as fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism in proposing, performing, or reviewing research, or in reporting research results. • Fabrication: making up data or results and recording or reporting them. • Falsification: manipulating research materials, equipment, or processes, or changing or omitting data or results, such that the research is not accurately represented in the research record. • Plagiarism: appropriation of another person’s ideas, processes, results, or words without giving appropriate credit. From: http://www.ostp.gov/cs/federal_policy_on_research_misconduct Federal definition continued • To be considered research misconduct, actions must: – represent a “significant departure from accepted practices” – have been “committed intentionally, or knowingly, or recklessly” – be “proven by a preponderance of evidence” • Research misconduct does not include honest error or difference of opinion • Official misconduct (FFP) not common, approx. 1 in 10,000 researchers confirmed cases annually; but… Questionable Research Practices (QRP) • Violation of standards (accepted, discipline, lab… standards) beyond the official (FFP) definition of research misconduct • Self-reports of misconduct or QRP (Nature, 2005) 3: – FFP violations: under 2% – QRP: 33% researchers engaged in at least one behavior judged (by university compliance officers) to be “sanctionable” offenses (probably an underestimate) • Much recent attention paid in articles, conference presentations, blogs to QRPs – More common; more impact than FFP (De Vries, et al) Martinson et al (2005) Rutgers Interim Academic Integrity Policy, 9/08 • Violations include: – Fabricating evidence, falsifying data, plagiarism – knowingly or negligently facilitating a violation of academic integrity by another person – Knowingly violating a canon of the ethical code of the profession for which a graduate or professional student is preparing • Any member of the Rutgers University community may report an alleged violation of the AIP to the faculty member teaching the course, to the Chair of the department, to the AIF of the school or college, or to the Office of Student Conduct. GSNB Academic Integrity: Issues for Grad Students distributed by GSNB, 2008 “As a Researcher: Data must be accurate and complete. Appropriate credit should be given to all who contribute to a project. The following actions would, in most cases, constitute a violation of the researcher’s ethical code: • • • • • • Falsify/fabricate data or results Selectively withhold data that contradicts your research Misuse the data of others Present data in a sloppy or deceptive manner Fail to maintain accurate laboratory notebooks Fail to credit authors appropriately. All contributors should be acknowledged Academic Integrity con’t • Sabotage/appropriate the research of another • Misuse research funds or university resources for personal use • Develop inappropriate research/industry relationships for personal gain • Fail to comply with federal and/or Rutgers guidelines for the treatment of human or animal subjects If you have questions about academic integrity, get them answered before jeopardizing your career. Speak to your faculty adviser, your graduate program director, or one of the Deans of the Graduate School-New Brunswick (732-9327747)” If you’re a TA • Rutgers Academic Integrity Policy also has guidelines for handling cheating or plagiarism in your classes. • Resources for Instructors: http://academicintegrity.rutgers.edu/instructors.shtml • Or consult faculty Suspicions of Misconduct “The circumstances surrounding potential violations of scientific standards are so varied that it is impossible to lay out a checklist of what should be done.”* • • • • • • Examine your own biases and motivations; remain objective Understand the standard you believe is being violated Be clear on the evidence Think about the interests/perspectives of everyone involved Think about the possible responses of those involved Consider if you can ask the person you suspect for clarification, or otherwise express your concern • Talk to a trusted advisor or friend • Consider alternative courses of action and their likely outcomes *National Academies Break-out groups (a) Pick someone to report to the group (b) Read and discuss case REPORT: (a) Summarize (or read) case to whole group (b) Review group discussion, consensus or majority & minority opinions, and especially reasoning processes Full group: comments/questions/discussion (4 case studies from National Academies, “On Being a Scientist) Issues to consider • Who has a stake in the situation? • What are the interests and perspectives of each of the parties? • Where do the stakeholders interests conflict? • What are the duties and obligations of the parties? What professional norms and values give rise to them? • What are the alternative courses of action? – And what are the likely consequences of each? (Bebeau et al., 1995) Evaluation of learning • Name the two most important things you learned about Research Misconduct that you did not know before this workshop. Explain your answer. Additional slides • The following case studies should be used as handouts for each of the breakout groups • Additional informational slides and references follow those Case #1: Discovering an error Two young faculty members—Marie, an epidemiologist in the medical school, and Yuan, a statistician in the mathematics department—have published two well-received papers about the spread of infections in populations. As Yuan is working on the simulation he has created to model infections, he realizes that a coding error has led to incorrect results that were published in the two papers. He sees, with great relief, that correcting the error does not change the average time it takes for an infection to spread. But the correct model exhibits greater uncertainty in its results, making predictions about the spread of an infection less definite. When he discusses the problem with Marie, she argues against sending corrections to the journals where the two earlier articles were published. “Both papers will be seen as suspect if we do that, and the changes don’t affect the main conclusions in the papers anyway,” she says. Their next paper will contain results based on the corrected model, and Yuan can post the corrected model on his Web page. 1. What obligations do the authors owe their professional colleagues to correct the published record? 2. How should their decisions be affected by how the model is being used by others? 3. What other options exist beyond publishing a formal correction? Case #2: Fabrication in a grant proposal Vijay, who has just finished his first year of graduate school, is applying to the National Science Foundation for a predoctoral fellowship. His work in a lab where he did a rotation project was later carried on successfully by others, and it appears that a manuscript will be prepared for publication by the end of the summer. However, the fellowship application deadline is June 1, and Vijay decides it would be advantageous to list a publication as “submitted” rather than “in progress.” Without consulting the faculty member or other colleagues involved, Vijay makes up a title and author list for a “submitted” paper and cites it in his application. After the application has been mailed, a lab member sees it and goes to the faculty member to ask about the “submitted” manuscript. Vijay admits to fabricating the submission of the paper but explains his actions by saying that he thought the practice was not uncommon in science. The faculty members in Vijay’s department demand that he withdraw his grant proposal and dismiss him from the graduate program. 1. Do you think that researchers often exaggerate the publication status of their work in written materials? 2. Do you think the department acted too harshly in dismissing Vijay from the graduate program? 3. If Vijay later applied to a graduate program at another institution, does that institution have the right to know what happened? 4. What were Vijay’s adviser’s responsibilities in reviewing the application before it was submitted? Case #3: Is it plagarism Professor Lee is writing a proposal for a research grant, and the deadline for the proposal submission is two days from now. To complete the background section of the proposal, Lee copies a few isolated sentences of a journal paper written by another author. The copied sentences consist of brief, factual, onesentence summaries of earlier articles closely related to the proposal, descriptions of basic concepts from textbooks, and definitions of standard mathematical notations. None of these ideas is due to the other author. Lee adds a one-sentence summary of the journal paper and cites it. 1. Does the copying of a few isolated sentences in this case constitute plagiarism? 2. By citing the journal paper, has Lee given proper credit to the other author? Case #4: A career in the balance Peter was just months away from finishing his Ph.D. dissertation when he realized that something was seriously amiss with the work of a fellow graduate student, Jimmy. Peter was convinced that Jimmy was not actually making the measurements he claimed to be making. They shared the same lab, but Jimmy rarely seemed to be there. Sometimes Peter saw research materials thrown away unopened. The results Jimmy was turning in to their common thesis adviser seemed too clean to be real. Peter knew that he would soon need to ask his thesis adviser for a letter of recommendation for faculty and postdoctoral positions. If he raised the issue with his adviser now, he was sure that it would affect the letter of recommendation. Jimmy was a favorite of his adviser, who had often helped Jimmy before when his project ran into problems. Yet Peter also knew that if he waited to raise the issue, the question would inevitably arise as to when he first suspected problems. Both Peter and his thesis adviser were using Jimmy’s results in their own research. If Jimmy’s data were inaccurate, they both needed to know as soon as possible. 1. What kind of evidence should Peter have to be able to go to his adviser? 2. Should Peter first try to talk with Jimmy, with his adviser, or with someone else entirely? 3. What other resources can Peter turn to for information that could help him decide what to do? General RCR discussion questions • Should researchers report misconduct if they are concerned that doing so could adversely impact their career? • Should other practices besides fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism be considered misconduct in research? • What evidence is needed to demonstrate that a researcher committed misconduct “intentionally, or knowingly, or recklessly”? • What are appropriate penalties for different types of misconduct? • What evidence is needed to demonstrate that a researcher committed misconduct “intentionally, or knowingly, or recklessly”? • Is it fair to use “significant departure from accepted practices” to make judgments about a researcher’s behavior? Judging responses to moral problems How does one decide whether a response is well-reasoned? Criteria: A. each of the issues and points of ethical conflict are addressed B. each interested party’s legitimate expectations are considered; C. the consequences of acting are recognized, specifically described (not just generally mentioned), and incorporated into the decision; and D. each of the duties or obligations of the protagonist are described and grounded in moral considerations. (from Bebeau, 1995) References • • • • • • • Bebeau, M.J., Pimple, K. D., Muskavitch, K. M. T., Borden, S. L. & Smith, D. H. (1995). Moral reasoning in scientific research. Cases for teaching and assessment. Accessed at http://poynter.indiana.edu/mr/mr-main.shtml De Vries, R., Anderson, M. S., and Martinson, B. C. (2006). Normal Misbehavior: Scientists Talk About the Ethics of Research. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 1(1), 43–50. Accessed online 8/11/09 at http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1483899 Hollander, R. (Ed.) (2009). Ethics Education and Scientific and Engineering Research: What's Been Learned? What Should Be Done? Summary of a Workshop. Accessed at http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12695.html Martinson, B.C., Anderson , M.S. & de Vries, R. (2005). Commentary: Scientists Behaving Badly. Nature 435, 737-738. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v435/n7043/full/435737a.html National Academy of Science. (2009). On Being a Scientist: A guide to responsible conduct in research. http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12192.html Pimple, K. D. (2005). Collaborative Research: Avoiding Pitfalls and Sharing Credit, K. D. Pimple, http://www.iupui.edu/~resed/collaborativereswkshp05intro.html Steneck, N. H. (2007) ORI Introduction to the Responsible Conduct of Research, Rev. ed. Additional bibliography and links • • • • • • • • • Office of Research Integrity (ORI): http://ori.hhs.gov/ (excellent resources) Council of Graduate Schools Project for Scholarly Integrity: http://www.scholarlyintegrity.org/ Council of Graduate Schools: Best practices in graduate education for the responsible conduct of research, 2008. National Academy of Engineering Online Ethics Center: http://www.onlineethics.org/ ; http://www.nae.edu/nae/engethicscen.nsf/weblinks/NKAL7LHM86?OpenDocument Codes of Ethics Online: http://ethics.iit.edu/codes/coe.html Anderson, M. S., Ronning, E.A., De Vries, R. & Martinson, B. C. (2007). The Perverse Effects of Competition on Scientists’ Work and Relationships. Sci Eng Ethics, Accessed online, 8/11/09, http://www.springerlink.com/content/l0764324110225n0/fulltext.pdf Odling-Smee, L., Giles, J. , Fuyuno, I., Cyranoski, D., & Marris, E. (2007). Misconduct special: Where are they now? Nature 445, 244-245 | doi:10.1038/445244a; Published online 17 January 2007 Syracuse University videos. Accessed at http://gradschpdprograms.syr.edu/resources/videos.php Goodman, Allegra. Intuition. (A novel) Bibliography, con’t • Ethics Education and Scientific and Engineering Research: What's Been Learned? What Should be Done?, 2009: http://www.nae.edu/?ID=14646 • National Digital Library for Ethics in Science & Engineering – Beta http://www.umass.edu/sts/digitallibrary/ • Programs involved in international collaborations, see http://tinyurl.com/l76p3b Rutgers University Links Academic Integrity Policy (9/2/08) http://academicintegrity.rutgers.edu/ http://policies.rutgers.edu/PDF/Section10/10.2.13-current.pdf • Graduate School – New Brunswick: Academic Issues for Graduate Students http://gsnb.rutgers.edu/publications/academic_integrity.pdf • University Policies for Dealing with Allegations of Misconduct in Research (1990) http://orsp.rutgers.edu/policies_misconduct.php • Ethics at Rutgers, http://uhr.rutgers.edu/ethics/ America COMPETES Act, 2007 & NSF, 2009 SEC. 7008. POSTDOCTORAL RESEARCH FELLOWS. (a) MENTORING.—The Director shall require that all grant applications that include funding to support postdoctoral researchers include a description of the mentoring activities that will be provided for such ... Mentoring activities may include… training in research ethics. SEC. 7009. RESPONSIBLE CONDUCT OF RESEARCH. The Director shall require that each institution that applies for financial assistance from the Foundation for science and engineering research or education describe in its grant proposal a plan to provide appropriate training and oversight in the responsible and ethical conduct of research to undergraduate students, graduate students, and postdoctoral researchers Available at: http://www.cfr.org/content/publications/attachments/2272.pdf NSF Regulations, 8/09: http://edocket.access.gpo.gov/2009/E9-19930.htm NJ Whistleblower Protection Law “NJ law prohibits an employer from taking any retaliatory action against an employee because the employee does any of the following: Discloses, or threatens to disclose…an activity, policy, or practice of the employer… that the employee reasonably believes is in violation of a law… Provides information to…any public body conducting an investigation, hearing or inquiry into any violation of law, or a rule or regulation … or Objects to, or refuses to participate in, any activity, policy or practice which the employee reasonably believes: – is in violation of a law, or a rule or regulation issued under the law… – is fraudulent or criminal; or – is incompatible with a clear mandate of public policy concerning the public health, safety or welfare or protection of the environment. “ The contact person to answer questions or provide information regarding your rights and responsibilities under this act: Harry Agnostak, Assistant Vice President for Human Resources http://uhr.rutgers.edu/lr/CEPA.htm