ENGL 2362.001 & 002 h: 903-566-4985

advertisement

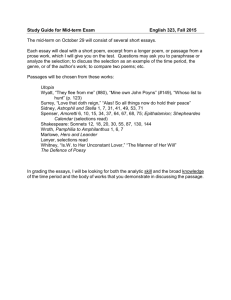

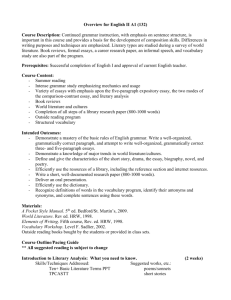

World Literature Through the Renaissance Dr. John Harris ENGL 2362.001 & 002 Spring 2012 Office: BUS 207a h: 903-566-4985 w: 903-565-5701 email: jharris@uttyler.edu Office Hours: MWF: 8:30-9, 10-11, 12-12:30 TTh: 8:30-9:30, 11-12:30 Required Texts/Materials The Macintosh iPad (II). All readings are in the form of three “pdf” files posted on Blackboard: no bound texts required, no purchase of discs or downloads necessary. Objectives: Any survey course seeks to provide an ample breadth of information (often, unfortunately, at the expense of depth). The objective in this class is for you to emerge with a general sense of major historical transitions in Western culture and of several significant authors whose work defined these transitions; furthermore, we shall aim to grow cursorily familiar with some of the world’s most influential texts and to understand how they relate chronologically and stylistically to our own traditions. Yet to suppose that we can even begin to cover all the world or all great literature, though the word “survey” be understood ever so broadly, would be presumptuous. (For instance, most of the non-Western works we shall study are Indo-Chinese: nothing from Japan, nothing from Africa, and just a bit from the Islamic world.) Hence my second general objective is based on the stylistic relationship mentioned above: you will acquire in this course a functional comprehension (which you will be able to apply to works and times not covered here) of the main characteristics distinguishing oral and literate cultures. The history of literature around the world has continually migrated along this spectrum, though at very differing rates. Hence the spectrum’s study is what the ancient Greeks would have called a “prolegomenon” (or necessary introduction) to the study of any complete literary tradition. I have accordingly broken this semester into three basic parts. First, through the ancient Greeks and Romans, we shall study how our own culture proceeded from an oral/tribal stage to a more literate/cosmopolitan stage; then we shall very briefly follow a similar sequence of stages in several Eastern cultures; and finally we shall return to Europe to observe how it achieved an unprecedented degree of literacy on the brink of what might be called modern times. I shall also strive to help you enjoy literature. The works of the past, especially those based in myth, frequently served religious, historical, and quasi-scientific ends without much thought to “aesthetic pleasure”, so we cannot simply assume that ancient authors intended to entertain us. Yet their assessment of religion, history, and science often turns out to be more aesthetic (that is, in search of an imaginative and poignant order) than they would have admitted. We need scarcely feel guilty, then, about stepping back and admiring the dream-like simplicity of their creations. In this course, you will learn how to unveil and admire the powerful narratives at work beneath odd or alien-seeming mythic surfaces. Finally, you will improve your analytical skills, not only through close reading and class discussion, but also and especially through writing. It is my particular objective that you continue your growth as thoughtful writers now that the freshman year is behind you. GRADING: Your grade will be determined through several means. Class Participation (40%): This component of the grade could actually reach 50% (see “additional 10%” below). Because we have such a massive amount of reading material to cover and no classes to waste on formal exams, daily quizzes are the obvious choice for evaluating who is keeping up with the assigned reading and how well. A brief quiz will be administered at the beginning of every class: it will sometimes have a multiple-choice or matching format, sometimes a short-answer one. The questions should prove quite simple for those who have done their work. Naturally, the quizzes must determine this grade far more than any other factor. Yet I try to create opportunities for verbal participation in every class, and I appreciate and reward those who contribute in this manner. While I cannot weigh verbal participation nearly as much as I do the quiz grade (since spoken participation is very difficult to evaluate objectively), I regularly use notations in my grade book to indicate which students have shined during class; and I often find that some of these, by the end of the semester, have logged enough verbal points to pull their quiz average up a full letter grade. I must point out that attendance is vital for this near-half of your total grade. I do not exact a fixed penalty for skipping a certain number of classes, but it should be plain to anyone that the kind of performance measured above requires students to be physically present. Your quiz grade will plummet quickly with slack attendance, you will of course contribute nothing to our discussions, and you will also not collect important information that should be included in essays. Essays (50%): You are required to write three essays in the course of the semester. Each of these is quite distinct in nature from the other two, so read the following descriptions carefully. Two Comparative/Contrastive Essay (15% each, 30% total): At the end of every section of readings in all of the files is a list of paper topics. Each list is labeled in red, “Questions for This Section”. The total number of questions for all three files is probably close to fifty, so you shouldn’t suffer from a dearth of options! At the beginning of File 1, you will find three “cultural profiles” that break down the essential stages of cultural evolution: oral-traditional, transitional, and literate. These profiles will be utterly critical in our attempt to make sense of a vast body of material coming to us from many parts of the world and from many eras. Review the profiles whenever you are considering an essay topic. In your essays, you will be directed to select two or more works from our readings. The essays are designated “comparative/contrastive” because their objective is critical analysis, NOT plot summary or historical scene-setting. Sometimes the amount of comparing and contrasting will be about equal. More often the question will instruct you that one kind of analysis should predominate. Always remember that you discussion should a) demonstrate an awareness of the cultural phases represented in the profiles, and b) refer fairly specifically to relevant evidence in the readings. Do not waste a lot of space citing lengthily from works.: summarize as needed. Do not throw citations before the reader and expect that your understanding of their value will be transparent: explain. Do not worry about consulting outside sources to supplement your judgments: you should be putting your own thinking on display. Do not fret about cover pages, font, formatting, or other cosmetic details: I’m looking for substance, not tinsel. A good paper will probably run about 1000 words, or three to four pages. I do not say that it MUST do so. I offer only a ballpark figure here. Papers may certainly exceed these restrictions. More is not necessarily better, but very little is probably not very good. Notice the submission deadlines on the schedule. The questions for each of the three files have a certain “shelf life” because, quite frankly, I cannot always remember whether or not you have already written about Gilgamesh and Achilles by the last week of classes. You might not believe it… but the occasional student will try to run the same essay by me twice for two grades! Survey Paper (20%): The word “survey” is French in origin: it means “overview” literally, as when one panoramically takes in a vast landscape. This is just the sort of view of the course materials that I expect from you at semester’s end. Essentially, this paper is your final exam. The same general rules apply here as were outlined just above for the compare/contrast essays. The topic this time will be laid out more broadly, however, so that your discussion may accommodate works from the beginning to the end of the reading list. In fact, you have a choice of three topics. They appear on the last page of the last file. You may glance over them now and have them in mind throughout the semester. The Survey Paper should of course run a little longer than the two previous essays. You may determine how much is adequate—but I would recommend five or six pages, at least To Repeat: none of these assignments is a research paper: you need make no trips to the library or visits to the Internet. They are exercises which call for judgment; that is, they do not so much discover “right answers” as they measure how well you are able to correlate specific textual facts (whose selection is up to you) to very general criteria. Continually refer to the broad thumbnail sketches of the cultural transition from orality to literacy presented early in File 1—the Cultural Profiles: these are your yardstick. The way you apply the yardstick will be crucial. Do the texts actually illustrate the points you raise about them (accuracy)? Have you indeed chosen useful illustrations, or are you just summarizing plots and “faking” your way through with airy formulations (clarity)? Do you connect the various points you raise in a coherent fashion (logical transition)? Do you use several points to develop your case rather than just one or two (thoroughness)? These four criteria will largely determine your grade. No Exams: Because we have so very much to read and discuss, and because I also have little faith in the timed-exam format to measure the kind of learning I hope to see, we will have no formal exams. I would regard them as wasting our time, under the circumstances. Additional 10%: The previous values add up to 90%. The remaining 10% I will bestow upon that portion of the grade where it will do you the most good. In other words, whichever of these four grades is highest—your Class Participation, your Compare/Contrast Essays Number One and Two, your Survey Paper—will automatically receive a boost of another 10% as I work up the final, overall grade. Grade Replacement If you are repeating this course for a grade replacement, you must file an intent to receive grade forgiveness with the registrar by the 12th day of class. Failure to file an intent to use grade forgiveness will result in both the original and repeated grade being used to calculate your overall grape point average. A student will receive grade forgiveness (grade replacement) for only three (undergraduate student) or two (graduate student) course repeats during his/her career at UT Tyler. (2006-08 Catalog, p. 35) Schedule of Readings and Assignments: Page numbers refer to the PDF’s posted on Blackboard for easy downloading: ALL readings are to be found in these files. Page numbers are approximate (I may make last-minute adjustments after drafting this syllabus). January 13: Opening discussion covering “Profiles of Cultural Phases” (5-10) in File 1; examples drawn from “The Boyhood Deeds of Cú Chulainn” in File 2 (from the Irish Táin Bó Cúalnge). 18: Read File 1, 11-38: The Shaman as Hero, The Epic of Gilgamesh (Old Babylonian Version), and The Epic of Gilgamesh (Modern Translation). 20: Read File 1, 39-49: excerpt from Apollodorus, “The Labors of Herakles.” 23: Read File 1, 50-71: Inklings of Complexity in Character and Society and The Iliad of Homer (books 1, 6, and excerpt from 11). 25: Read File 1, 72-89: The Iliad of Homer (excerpt from book 16, books 22 and 24). 27: 30: Read File 1, 90-109: Homer’s Odyssey (books 1-2, 6). Read File 1, 109-123 and 135-144: Homer’s Odyssey (books 9-10, 13). February 1: Read File 1, 145-175: Homer’s Odyssey (books 17-22). 3: Read File 1, 176-193: “Proverbs: A Selection from Southwestern Ireland” and “The Fables of Aesop”. 6: Read File 1, 195-211: Writing as a Tool to Refine Oral Traditions, Selection from Herodotus’ Histories, Solon #1 of Surviving Fragments. 8: Read File 1, 213-215, 264-277: Writing: Logic Revises Tradition, excerpt from Longus’ Daphis and Chloe, and Selections from Apuleius’ Golden Ass. 10: Read File 1, 280-294: Logic Revises Tradition, Selections from Plato’s Apology of Socrates and Selections from the Discourses of Epictetus. 13: Read File 1, 300-326: Virgil’s Aeneid (books 1 and 2). 15: Read File 1, 327-341: Virgil’s Aeneid (book 4). 17: Read File 1, 341-149: Virgil’s Aeneid (excerpts from books 6, 10, and 12). 20: Read File 1, 360-370:Selection from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. 22: Read File 1, 348-354: “Scipio’s Dream” from Cicero’s De Re Publica 24: Read File 1, 377-384:Selection from Tacitus’s Germania. Change to File 2 27: Read File 2, 3-4, 28-41: Persia/Iran: Remnants of Oral Tradition, and Selections from The Thousand and One Nights. 29: Read File 2, 45-58: Chapters 1 and 2 of the Bhagavad Gita. March 2: Read File 2, 66-80: excerpts from the Panchatantra and from Somadeva’s Kathasaritsagara. 5: Read File 2, 81-104: Kalidasa’s Shakuntala Acts I-III. 7: Finish discussing Shakuntala; Deadline for submission of first essay. 12- S P R I N G 16 B R E A K. 19: Read File 2, 132-144: “China: Likenesses of Uncertain Beginning or End,” and excerpts from The Analects of Confucius. 21: Read File 2, 145-168: Yüan Chen’s “The Story of Ying-Ying” and Wang Shifu’s Romance of the Western Wing (final act only). 23: Read File 2, 161-176, 181-193: Chinese poets T’ao Ch’ien, Han-Shan, and Li Po. Change to File 3. 26: Read File 3, 3-21: “The Middle Ages: Mythic Traditions Adapted to a New View of the Soul,” and excerpts from Beowulf. 28: Read File 3, 50-83: “Later Texts” and The Wasting-Sickness of Cú Chulainn. 30: Read File 3, 84-111: Marie de France’s Lay of Eliduc. April 2: Read File 3, 123-143: Books 1 and 2 of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. 4: Read File 3, 143-160: Books 3 and 4 of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. 6: Read File 3, 161-183: The Adventure of Melora and Orlando. 9: Read File 3, 184-207: Dante’s Inferno (Cantos 1-6). 11: Read File 3, 212-235: Dante’s Inferno (Cantos 21-22, 26, 32-34). 13: Read File 3, 237-252: “The Renaissance: Alienation from the Past, Liberation to SelfDiscovery,” and Selections from Machiavelli’s Prince. 16: Read File 3, 303-313: Montaigne’s “Of Cannibals.” Deadline for submission of second essay. 18: Read File 3, 253-274: Introduction and Canto 1 from Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso. 20: Read File 3, 274-302: Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, excerpts from Cantos 2 and 3. 23: Read File 3, 314-332 and 344-349: Cervantes’s Don Quixote (Part 1, chapters 1-5; Part 2, chapter 17). 25: Read File 3, 350-386: Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, Acts I and II. 27: Read File 3, 386-429: Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, Acts III and V. 30: Finish discussion of Shakespeare. May 2: Read File 3, 431-442: Bonus Assignment—Ben Okri’s “Worlds That Flourish.” 4: S T U D Y 7: D A Y S. 9: Deadline at noon for Survey Paper (bring to BUS 207a, deliver to Lang & Lit Department at BUS 237, or send to reliable e-mail address).