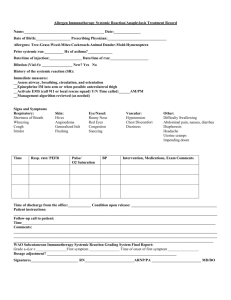

Systemic Risk Bibliography

advertisement