PPT: Collecting Classroom Data/Defining Student Behavior

advertisement

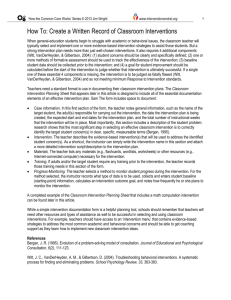

Response to Intervention RTI: Giving the Classroom Teacher the Necessary Tools to Serve as an Intervention ‘First Responder’ Jim Wright www.interventioncentral.org www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Workshop Agenda Writing Clear, Specific Student Academic & Behavioral Problem Identification Statements Review of Selected Tier 1 (Classroom) Instruction and Intervention Ideas Review of Classroom-Friendly Methods of Progress-Monitoring Discussion About Free Internet Resources to Help Teachers to Be Intervention ‘First Responders’ www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention RTI ‘Pyramid of Interventions’ Tier 3 Tier 2 Tier 1 Tier 3: Intensive interventions. Students who are ‘nonresponders’ to Tiers 1 & 2 are referred to the RTI Team for more intensive interventions. Tier 2 Individualized interventions. Subset of students receive interventions targeting specific needs. Tier 1: Universal interventions. Available to all students in a classroom or school. Can consist of whole-group or individual strategies or supports. www.interventioncentral.org 4 Response to Intervention Source: New York State Education Department. (October 2010). Response to Intervention: Guidance for New York State School Districts. Retrieved November 10, 2010, from http://www.p12.nysed.gov/specialed/RTI/guidance-oct10.pdf; p. 12 www.interventioncentral.org 5 Response to Intervention Tier 1 Core Instruction Tier I core instruction: • Is universal—available to all students. • Can be delivered within classrooms or throughout the school. • Is an ongoing process of developing strong classroom instructional practices to reach the largest number of struggling learners. All children have access to Tier 1 instruction/interventions. Teachers have the capability to use those strategies without requiring outside assistance. Tier 1 instruction encompasses: • The school’s core curriculum. • All published or teacher-made materials used to deliver that curriculum. • Teacher use of ‘whole-group’ teaching & management strategies. Tier I instruction addresses this question: Are strong classroom instructional strategies sufficient to help the student to achieve academic success? www.interventioncentral.org 6 Response to Intervention Tier I (Classroom) Intervention Tier 1 intervention: • Targets ‘red flag’ students who are not successful with core instruction alone. • Uses ‘evidence-based’ strategies to address student academic or behavioral concerns. • Must be feasible to implement given the resources available in the classroom. Tier I intervention addresses the question: Does the student make adequate progress when the instructor uses specific academic or behavioral strategies matched to the presenting concern? www.interventioncentral.org 7 Response to Intervention The Key Role of Classroom Teachers as ‘Interventionists’ in RTI: 6 Steps 1. The teacher defines the student academic or behavioral problem clearly. 2. The teacher decides on the best explanation for why the problem is occurring. 3. The teacher selects ‘evidence-based’ interventions. 4. The teacher documents the student’s Tier 1 intervention plan. 5. The teacher monitors the student’s response (progress) to the intervention plan. 6. The teacher knows what the next steps are when a student fails to make adequate progress with Tier 1 interventions alone. www.interventioncentral.org 8 Response to Intervention RTI & Intervention: Key Concepts www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Core Instruction, Interventions, Accommodations & Modifications: Sorting Them Out • Core Instruction. Those instructional strategies that are used routinely with all students in a generaleducation setting are considered ‘core instruction’. High-quality instruction is essential and forms the foundation of RTI academic support. NOTE: While it is important to verify that good core instructional practices are in place for a struggling student, those routine practices do not ‘count’ as individual student interventions. www.interventioncentral.org 10 Response to Intervention Core Instruction, Interventions, Accommodations & Modifications: Sorting Them Out • Intervention. An academic intervention is a strategy used to teach a new skill, build fluency in a skill, or encourage a child to apply an existing skill to new situations or settings. An intervention can be thought of as “a set of actions that, when taken, have demonstrated ability to change a fixed educational trajectory” (Methe & Riley-Tillman, 2008; p. 37). www.interventioncentral.org 11 Response to Intervention Core Instruction, Interventions, Accommodations & Modifications: Sorting Them Out • Accommodation. An accommodation is intended to help the student to fully access and participate in the generaleducation curriculum without changing the instructional content and without reducing the student’s rate of learning (Skinner, Pappas & Davis, 2005). An accommodation is intended to remove barriers to learning while still expecting that students will master the same instructional content as their typical peers. – Accommodation example 1: Students are allowed to supplement silent reading of a novel by listening to the book on tape. – Accommodation example 2: For unmotivated students, the instructor breaks larger assignments into smaller ‘chunks’ and providing students with performance feedback and praise for each completed ‘chunk’ of assigned work (Skinner, Pappas & Davis, 2005). www.interventioncentral.org 12 Response to Intervention “ “Teaching is giving; it isn’t taking away.” ” (Howell, Hosp & Kurns, 2008; p. 356). Source: Howell, K. W., Hosp, J. L., & Kurns, S. (2008). Best practices in curriculum-based evaluation. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology V (pp.349-362). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists.. www.interventioncentral.org 13 Response to Intervention Core Instruction, Interventions, Accommodations & Modifications: Sorting Them Out • Modification. A modification changes the expectations of what a student is expected to know or do—typically by lowering the academic standards against which the student is to be evaluated. Examples of modifications: – Giving a student five math computation problems for practice instead of the 20 problems assigned to the rest of the class – Letting the student consult course notes during a test when peers are not permitted to do so www.interventioncentral.org 14 Response to Intervention Good Behavior Game (Barrish, Saunders, & Wold, 1969) www.interventioncentral.org 15 Response to Intervention Sample Classroom Management Strategy: Good Behavior Game (Barrish, Saunders, & Wold, 1969) The Good Behavior Game is a whole-class intervention to improve student attending and academic engagement. It is best used during structured class time: for example, whole-group instruction or periods of independent seatwork Description: The class is divided into two or more student teams. The teacher defines a small set of 2 to 3 negative behaviors. When a student shows a problem behavior, the teacher assigns a negative behavior ‘point’ to that student’s team. At the end of the Game time period, any team whose number of points falls below a ‘cut-off’ set by the teacher earns a daily reward or privilege. Guidelines for using this intervention: The Game is ideal to use with the entire class during academic study or lecture periods to keep students academically engaged The Game is not suitable for less-structured activities such as cooperative learning groups, where students are expected to interact with each other as part of the work assignment. www.interventioncentral.org 16 Response to Intervention Good Behavior Game: Steps 1. The instructor decides when to schedule the Game. (NOTE: Generally, the Good Behavior Game should be used for no more than 45 to 60 minutes per day to maintain its effectiveness.) 2. The instructor defines the 2-3 negative behaviors that will be scored during the Game. Most teachers use these 3 categories: • Talking Out: The student talks, calls out, or otherwise verbalizes without teacher permission. • Out of Seat: The student’s posterior is not on the seat. • Disruptive Behavior: The student engages in any other behavior that the instructor finds distracting or problematic. www.interventioncentral.org 17 Response to Intervention Good Behavior Game: Steps 3. 4. 5. The instructor selects a daily reward to be awarded to each member of successful student teams. (HINT: Try to select rewards that are inexpensive or free. For example, student winners might be given a coupon permitting them to skip one homework item that night.) The instructor divides the class into 2 or more teams. The instructor selects a daily cut-off level that represents the maximum number of points that a team is allowed (e.g., 5 points). www.interventioncentral.org 18 Response to Intervention Good Behavior Game: Steps 6. When the Game is being played, the instructor teaches in the usual manner. Whenever the instructor observes student misbehavior during the lesson, the instructor silently assigns a point to that student’s team (e.g., as a tally mark on the board) and continues to teach. 7. When the Game period is over, the teacher tallies each team’s points. Here are the rules for deciding the winner(s) of the Game: • Any team whose point total is at or below the pre-determined cut-off earns the daily reward. (NOTE: This means that more than one team can win!) • If one team’s point total is above the cut-off level, that team does not earn a reward. • If ALL teams have point totals that EXCEED the cut-off level for that day, only the team with the LOWEST number of points wins. www.interventioncentral.org 19 Response to Intervention Good Behavior Game: Troubleshooting Here are some tips for using the Good Behavior Game: • Avoid the temptation to overuse the Game. Limit its use to no more than 45 minutes to an hour per day. • If a student engages in repeated bad behavior to sabotage a team and cause it to lose, you can create an additional ‘team of one’ that has only one member--the misbehaving student. This student can still participate in the Game but is no longer able to spoil the Game for peers! • If the Game appears to be losing effectiveness, check to be sure it is being implemented with care and that you are: – Assigning points consistently when you observe misbehavior. – Not allowing yourself to be pulled into arguments with students when you assign points for misbehavior. – Reliably giving rewards to Game winners. – Not overusing the Game. www.interventioncentral.org 20 Response to Intervention Good Behavior Game Team 1 Cut-Off=2 Team 2 Game Over [Out of Seat] [Disruptive] [Call Out] Answer: teams won thethis Game, as both teams’ point totals fell Question:Both Which team won Game? BELOW the cut-off of 5 points. www.interventioncentral.org 21 Response to Intervention Promoting Student Reading Comprehension ‘FixUp’ Skills Jim Wright www.interventioncentral.org www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Reading Comprehension ‘Fix-Up’ Skills: A Toolkit Good readers continuously monitor their understanding of informational text. When necessary, they also take steps to improve their understanding of text through use of reading comprehension ‘fix-up’ skills. Presented here are a series of fix-up skill strategies that can help struggling students to better understand difficult reading assignments… www.interventioncentral.org 23 Response to Intervention Reading Comprehension ‘Fix-Up’ Skills: A Toolkit (Cont.) • [Core Instruction] Providing Main Idea Practice through ‘Partner Retell’ (Carnine & Carnine, 2004). Students in a group or class are assigned a text selection to read silently. Students are then paired off, with one student assigned the role of ‘reteller’ and the other appointed as ‘listener’. The reteller recounts the main idea to the listener, who can comment or ask questions. The teacher then states the main idea to the class. Next, the reteller locates two key details from the reading that support the main idea and shares these with the listener. At the end of the activity, the teacher does a spot check by randomly calling on one or more students in the listener role and asking them to recap what information was shared by the reteller. www.interventioncentral.org 24 Response to Intervention Reading Comprehension ‘Fix-Up’ Skills: A Toolkit (Cont.) • [Accommodation] Developing a Bank of Multiple Passages to Present Challenging Concepts (Hedin & Conderman, 2010; Kamil et al., 2008; Texas Reading Initiative, 2002). The teacher notes which course concepts, cognitive strategies, or other information will likely present the greatest challenge to students. For these ‘challenge’ topics, the teacher selects alternative readings that present the same general information and review the same key vocabulary as the course text but that are more accessible to struggling readers (e.g., with selections written at an easier reading level or that use graphics to visually illustrate concepts). These alternative selections are organized into a bank that students can access as a source of ‘wide reading’ material. www.interventioncentral.org 25 Response to Intervention Reading Comprehension ‘Fix-Up’ Skills: A Toolkit (Cont.) • [Student Strategy] Promoting Understanding & Building Endurance through Reading-Reflection Pauses (Hedin & Conderman, 2010). The student decides on a reading interval (e.g., every four sentences; every 3 minutes; at the end of each paragraph). At the end of each interval, the student pauses briefly to recall the main points of the reading. If the student has questions or is uncertain about the content, the student rereads part or all of the section just read. This strategy is useful both for students who need to monitor their understanding as well as those who benefit from brief breaks when engaging in intensive reading as a means to build up endurance as attentive readers. www.interventioncentral.org 26 Response to Intervention Reading Comprehension ‘Fix-Up’ Skills: A Toolkit (Cont.) • [Student Strategy] Identifying or Constructing Main Idea Sentences (Davey & McBride, 1986; Rosenshine, Meister & Chapman, 1996). For each paragraph in an assigned reading, the student either (a) highlights the main idea sentence or (b) highlights key details and uses them to write a ‘gist’ sentence. The student then writes the main idea of that paragraph on an index card. On the other side of the card, the student writes a question whose answer is that paragraph’s main idea sentence. This stack of ‘main idea’ cards becomes a useful tool to review assigned readings. www.interventioncentral.org 27 Response to Intervention Reading Comprehension ‘Fix-Up’ Skills: A Toolkit (Cont.) • [Student Strategy] Restructuring Paragraphs with Main Idea First to Strengthen ‘Rereads’ (Hedin & Conderman, 2010). The student highlights or creates a main idea sentence for each paragraph in the assigned reading. When rereading each paragraph of the selection, the student (1) reads the main idea sentence or student-generated ‘gist’ sentence first (irrespective of where that sentence actually falls in the paragraph); (2) reads the remainder of the paragraph, and (3) reflects on how the main idea relates to the paragraph content. www.interventioncentral.org 28 Response to Intervention Reading Comprehension ‘Fix-Up’ Skills: A Toolkit (Cont.) • [Student Strategy] Summarizing Readings (Boardman et al., 2008). The student is taught to summarize readings into main ideas and essential details--stripped of superfluous content. The act of summarizing longer readings can promote understanding and retention of content while the summarized text itself can be a useful study tool. www.interventioncentral.org 29 Response to Intervention Reading Comprehension ‘Fix-Up’ Skills: A Toolkit (Cont.) • [Student Strategy] Linking Pronouns to Referents (Hedin & Conderman, 2010). Some readers lose the connection between pronouns and the nouns that they refer to (known as ‘referents’)—especially when reading challenging text. The student is encouraged to circle pronouns in the reading, to explicitly identify each pronoun’s referent, and (optionally) to write next to the pronoun the name of its referent. For example, the student may add the referent to a pronoun in this sentence from a biology text: “The Cambrian Period is the first geological age that has large numbers of multi-celled organisms associated with it Cambrian Period.” www.interventioncentral.org 30 Response to Intervention Reading Comprehension ‘Fix-Up’ Skills: A Toolkit (Cont.) • Student Strategy] Apply Vocabulary ‘Fix-Up’ Skills for Unknown Words (Klingner & Vaughn, 1999). When confronting an unknown word in a reading selection, the student applies the following vocabulary ‘fix-up’ skills: 1. Read the sentence again. 2. Read the sentences before and after the problem sentence for clues to the word’s meaning. 3. See if there are prefixes or suffixes in the word that can give clues to meaning. 4. Break the word up by syllables and look for ‘smaller words’ within. www.interventioncentral.org 31 Response to Intervention Reading Comprehension ‘Fix-Up’ Skills: A Toolkit (Cont.) • [Student Strategy] Compiling a Vocabulary Journal from Course Readings (Hedin & Conderman, 2010). The student highlights new or unfamiliar vocabulary from course readings. The student writes each term into a vocabulary journal, using a standard ‘sentence-stem’ format: e.g., “Mitosis means…” or “A chloroplast is…”. If the student is unable to generate a definition for a vocabulary term based on the course reading, he or she writes the term into the vocabulary journal without definition and then applies other strategies to define the term: e.g., look up the term in a dictionary; use Google to locate two examples of the term being used correctly in context; ask the instructor, etc.). www.interventioncentral.org 32 Response to Intervention Reading Comprehension ‘Fix-Up’ Skills: A Toolkit (Cont.) • [Student Strategy] Encouraging Student Use of Text Enhancements (Hedin & Conderman, 2010). Text enhancements can be used to tag important vocabulary terms, key ideas, or other reading content. If working with photocopied material, the student can use a highlighter to note key ideas or vocabulary. Another enhancement strategy is the ‘lasso and rope’ technique—using a pen or pencil to circle a vocabulary term and then drawing a line that connects that term to its underlined definition. If working from a textbook, the student can cut sticky notes into strips. These strips can be inserted in the book as pointers to text of interest. They can also be used as temporary labels—e.g., for writing a vocabulary term and its definition. www.interventioncentral.org 33 Response to Intervention Reading Comprehension ‘Fix-Up’ Skills: A Toolkit (Cont.) • [Student Strategy] Reading Actively Through Text Annotation (Harris, 1990; Sarkisian et al., 2003). Students are likely to increase their retention of information when they interact actively with their reading by jotting comments in the margin of the text. Using photocopies, the student is taught to engage in an ongoing 'conversation' with the writer by recording a running series of brief comments in the margins of the text. The student may write annotations to record opinions about points raised by the writer, questions triggered by the reading, or unknown vocabulary words. www.interventioncentral.org 34 Response to Intervention ‘Defensive Behavior Management’: The Power of Teacher Preparation Jim Wright www.interventioncentral.org www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Defensive Management: A Method to Avoid Power Struggles ‘Defensive management’ (Fields, 2004) is a teacherfriendly six-step approach to avert student-teacher power struggles that emphasizes providing proactive instructional support to the student, elimination of behavioral triggers in the classroom setting, relationship-building, strategic application of defusing techniques when needed, and use of a ‘reconnection’ conference after behavioral incidents to promote student reflection and positive behavior change. Source: Fields, B. (2004). Breaking the cycle of office referrals and suspensions: Defensive management. Educational Psychology in Practice, 20, 103-115. www.interventioncentral.org 36 Response to Intervention Defensive Management: Six Steps 1. Understanding the Problem and Using Proactive Strategies. The teacher collects information--through direct observation and perhaps other means--about specific instances of student problem behavior and the instructional components and other factors surrounding them. The teacher analyzes this information to discover specific ‘trigger’ events that seem to set off the problem behavior(s) (e.g., lack of skills; failure to understand directions). The instructor then adjusts instruction to provide appropriate student support (e.g., providing the student with additional instruction in a skill; repeating directions and writing them on the board). Source: Fields, B. (2004). Breaking the cycle of office referrals and suspensions: Defensive management. Educational Psychology in Practice, 20, 103-115. www.interventioncentral.org 37 Response to Intervention Defensive Management: Six Steps 2. Promoting Positive Teacher-Student Interactions. Early in each class session, the teacher has at least one positive verbal interaction with the student. Throughout the class period, the teacher continues to interact in positive ways with the student (e.g., brief conversation, smile, thumbs up, praise comment after a student remark in large-group discussion, etc.). In each interaction, the teacher adopts a genuinely accepting, polite, respectful tone. Source: Fields, B. (2004). Breaking the cycle of office referrals and suspensions: Defensive management. Educational Psychology in Practice, 20, 103-115. www.interventioncentral.org 38 Response to Intervention Defensive Management: Six Steps 3. Scanning for Warning Indicators. During the class session, the teacher monitors the target student’s behavior for any behavioral indicators suggesting that the student is becoming frustrated or angry. Examples of behaviors that precede non-compliance or open defiance may include stopping work; muttering or complaining; becoming argumentative; interrupting others; leaving his or her seat; throwing objects, etc.). Source: Fields, B. (2004). Breaking the cycle of office referrals and suspensions: Defensive management. Educational Psychology in Practice, 20, 103-115. www.interventioncentral.org 39 Response to Intervention Defensive Management: Six Steps 4. Exercising Emotional Restraint. Whenever the student begins to display problematic behaviors, the teacher makes an active effort to remain calm. To actively monitor his or her emotional state, the teacher tracks physiological cues such as increased muscle tension and heart rate, as well as fear, annoyance, anger, or other negative emotions. The teacher also adopts calming or relaxation strategies that work for him or her in the face of provocative student behavior, such as taking a deep breath or counting to 10 before responding. Source: Fields, B. (2004). Breaking the cycle of office referrals and suspensions: Defensive management. Educational Psychology in Practice, 20, 103-115. www.interventioncentral.org 40 Response to Intervention Defensive Management: Six Steps 5. Using Defusing Tactics. If the student begins to escalate to non-compliant, defiant, or confrontational behavior (e.g., arguing, threatening, other intentional verbal interruptions), the teacher draws from a range of possible descalating strategies to defuse the situation. Such strategies can include private conversation with the student while maintaining a calm voice, open-ended questions, paraphrasing the student’s concerns, acknowledging the student’s emotions, etc. Source: Fields, B. (2004). Breaking the cycle of office referrals and suspensions: Defensive management. Educational Psychology in Practice, 20, 103-115. www.interventioncentral.org 41 Response to Intervention Defensive Management: Six Steps 6. Reconnecting with The Student. Soon after any in-class incident of student non-compliance, defiance, or confrontation, the teacher makes a point to meet with the student to discuss the behavioral incident, identify the triggers in the classroom environment that led to the problem, and brainstorm with the student to create a written plan to prevent the reoccurrence of such an incident. Throughout this conference, the teacher maintains a supportive, positive, polite, and respectful tone. Source: Fields, B. (2004). Breaking the cycle of office referrals and suspensions: Defensive management. Educational Psychology in Practice, 20, 103-115. www.interventioncentral.org 42 Response to Intervention Defining Student Problem Behaviors: A Key to Identifying Effective Interventions p. 70 Jim Wright www.interventioncentral.org www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Create a Problem Behavior Identification Statement • At your tables: – Discuss students whose behaviors pose a challenge in your classroom or school. – Select one of those students discussed. – For that student, write down a ‘problem identification statement’ that describes the problem behavior. www.interventioncentral.org 44 Response to Intervention Defining Problem Student Behaviors… 1. Define the problem behavior in clear, observable, measurable terms (Batsche et al., 2008; Upah, 2008). Write a clear description of the problem behavior. Avoid vague problem identification statements such as “The student is disruptive.” A well-written problem definition should include three parts: – Conditions. The condition(s) under which the problem is likely to occur – Problem Description. A specific description of the problem behavior – Contextual information. Information about the frequency, intensity, duration, or other dimension(s) of the behavior that provide a context for estimating the degree to which the behavior presents a problem in the setting(s) in which it occurs. www.interventioncentral.org 45 Response to Intervention www.interventioncentral.org 46 Response to Intervention Defining Student Problem Behaviors: Team Activity Using the student selected by your team: • Step 1: Define the problem behavior in clear, observable, measurable terms. Five Steps in Understanding & Addressing Problem Behaviors: 1. Define the problem behavior in clear, observable, measurable terms. 2. Develop examples and nonexamples of the problem behavior. 3. Write a behavior hypothesis statement. 4. Select a replacement behavior. 5. Write a prediction statement. www.interventioncentral.org 47 Response to Intervention Defining Problem Student Behaviors… 2. Develop examples and non-examples of the problem behavior (Upah, 2008). Writing both examples and nonexamples of the problem behavior helps to resolve uncertainty about when the student’s conduct should be classified as a problem behavior. Examples should include the most frequent or typical instances of the student problem behavior. Nonexamples should include any behaviors that are acceptable conduct but might possibly be confused with the problem behavior. www.interventioncentral.org 48 Response to Intervention www.interventioncentral.org 49 Response to Intervention Defining Student Problem Behaviors: Team Activity Using the student selected by your team: • Step 2: Develop examples and nonexamples of the problem behavior. Five Steps in Understanding & Addressing Problem Behaviors: 1. Define the problem behavior in clear, observable, measurable terms. 2. Develop examples and nonexamples of the problem behavior. 3. Write a behavior hypothesis statement. 4. Select a replacement behavior. 5. Write a prediction statement. www.interventioncentral.org 50 Response to Intervention Defining Problem Student Behaviors… 3. Write a behavior hypothesis statement (Batsche et al., 2008; Upah, 2008). The next step in problem-solving is to develop a hypothesis about why the student is engaging in an undesirable behavior or not engaging in a desired behavior. Teachers can gain information to develop a hypothesis through direct observation, student interview, review of student work products, and other sources. The behavior hypothesis statement is important because (a) it can be tested, and (b) it provides guidance on the type(s) of interventions that might benefit the student. www.interventioncentral.org 51 Response to Intervention www.interventioncentral.org 52 Response to Intervention Defining Student Problem Behaviors: Team Activity Using the student selected by your team: • Step 3: Write a behavior hypothesis statement. Five Steps in Understanding & Addressing Problem Behaviors: 1. Define the problem behavior in clear, observable, measurable terms. 2. Develop examples and nonexamples of the problem behavior. 3. Write a behavior hypothesis statement. 4. Select a replacement behavior. 5. Write a prediction statement. www.interventioncentral.org 53 Response to Intervention Defining Problem Student Behaviors… 4. Select a replacement behavior (Batsche et al., 2008). Behavioral interventions should be focused on increasing student skills and capacities, not simply on suppressing problem behaviors. By selecting a positive behavioral goal that is an appropriate replacement for the student’s original problem behavior, the teacher reframes the student concern in a manner that allows for more effective intervention planning. www.interventioncentral.org 54 Response to Intervention www.interventioncentral.org 55 Response to Intervention Defining Student Problem Behaviors: Team Activity Using the student selected by your team: • Step 4: Select a replacement behavior. Five Steps in Understanding & Addressing Problem Behaviors: 1. Define the problem behavior in clear, observable, measurable terms. 2. Develop examples and nonexamples of the problem behavior. 3. Write a behavior hypothesis statement. 4. Select a replacement behavior. 5. Write a prediction statement. www.interventioncentral.org 56 Response to Intervention Defining Problem Student Behaviors… 5. Write a prediction statement (Batsche et al., 2008; Upah, 2008). The prediction statement proposes a strategy (intervention) that is predicted to improve the problem behavior. The importance of the prediction statement is that it spells out specifically the expected outcome if the strategy is successful. The formula for writing a prediction statement is to state that if the proposed strategy (‘Specific Action’) is adopted, then the rate of problem behavior is expected to decrease or increase in the desired direction. www.interventioncentral.org 57 Response to Intervention www.interventioncentral.org 58 Response to Intervention Defining Student Problem Behaviors: Team Activity Using the student selected by your team: • Step 5: Write a prediction statement. Five Steps in Understanding & Addressing Problem Behaviors: 1. Define the problem behavior in clear, observable, measurable terms. 2. Develop examples and nonexamples of the problem behavior. 3. Write a behavior hypothesis statement. 4. Select a replacement behavior. 5. Write a prediction statement. www.interventioncentral.org 59 Response to Intervention www.interventioncentral.org 60 Response to Intervention Team Activity: Planning for ‘Next Steps’ At your tables: • Consider the 5-step framework that was just reviewed for identifying student behavior problems. • Create the first steps of a plan to share this framework with teachers in your school to help them to better solve student problems. www.interventioncentral.org 61 Response to Intervention Methods of Classroom Data Collection Jim Wright www.interventioncentral.org www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Classroom Data Collection Existing data. The teacher uses information already being collected in the classroom or school that is relevant to the identified student problem. Examples of existing data include: – – – – grades attendance/tardy records, office disciplinary referrals homework completion • NOTE: Existing data is often not sufficient alone to monitor a student on intervention but can be a useful supplemental source of data on academic or behavioral performance. www.interventioncentral.org 63 Response to Intervention Existing Data: Example Example: Mrs. Berman, a high-school social studies teacher, selected grades from weekly quizzes as one measure to determine if a study-skills intervention would help Rick, a student in her class. Prior to the intervention, the teacher computed the average of Rick’s most recent 4 quiz grades. The baseline average quiz grade for Rick was 61. Mrs. Smith set an average quiz grade of 75 as the intervention goal. The teacher decided that at the intervention check-up in six weeks, she would average the most recent 2 weekly quiz grades to see if the student reached the goal. www.interventioncentral.org 64 Response to Intervention Classroom Data Collection Global skill checklist. The teacher selects a global skill (e.g., homework completion; independent seatwork). The teacher then breaks the global skill down into a checklist of component sub-skills--a process known as ‘discrete categorization’ (Kazdin, 1989). An observer (e.g., teacher, another adult, or even the student) can then use the checklist to note whether a student successfully displays each of the sub-skills on a given day. Classroom teachers can use these checklists as convenient tools to assess whether a student has the minimum required range of academic enabling skills for classroom success. www.interventioncentral.org 65 Response to Intervention Global Skills Checklist: Example • Example: A middle school math instructor, Mr. Haverneck, was concerned that a student, Rodney, appears to have poor ‘organization skills’. Mr. Haverneck created a checklist of observable subskills that, in his opinion, were part of the global term ‘organization skills: – arriving to class on time; – bringing work materials to class; – following teacher directions in a timely manner; – knowing how to request teacher assistance when needed; – having an uncluttered desk with only essential work materials. Mr. Havernick monitored the student’s compliance with elements of this organization -skills checklist across three days of math class. On average, Rodney successfully carried out only 2 of the 5 possible subskills (baseline). Mr. Havernick set the goal that by the last week of a 5-week intervention, the student would be found to use all five of the subskills on at least 4 out of 5 days. www.interventioncentral.org 66 Response to Intervention ‘Academic Enabler’ Observational Checklists: Measuring Students’ Ability to Manage Their Own Learning www.interventioncentral.org 67 Response to Intervention ‘Academic Enabler’ Skills: Why Are They Important? Student academic success requires more than content knowledge or mastery of a collection of cognitive strategies. Academic accomplishment depends also on a set of ancillary skills and attributes called ‘academic enablers’ (DiPerna, 2006). Examples of academic enablers include: – – – – – Study skills Homework completion Cooperative learning skills Organization Independent seatwork Source: DiPerna, J. C. (2006). Academic enablers and student achievement: Implications for assessment and intervention services in the schools. Psychology in the Schools, 43, 7-17. www.interventioncentral.org 68 Response to Intervention ‘Academic Enabler’ Skills: Why Are They Important? (Cont.) Because academic enablers are often described as broad skill sets, however, they can be challenging to define in clear, specific, measureable terms. A useful method for defining a global academic enabling skill is to break it down into a checklist of component subskills--a process known as ‘discrete categorization’ (Kazdin, 1989). An observer can then use the checklist to note whether a student successfully displays each of the sub-skills. Source: Kazdin, A. E. (1989). Behavior modification in applied settings (4th ed.). Pacific Gove, CA: Brooks/Cole. www.interventioncentral.org 69 Response to Intervention ‘Academic Enabler’ Skills: Why Are They Important? (Cont.) Observational checklists that define academic enabling skills have several uses in Response to Intervention: – Classroom teachers can use these skills checklists as convenient tools to assess whether a student possesses the minimum ‘starter set’ of academic enabling skills needed for classroom success. – Teachers or tutors can share examples of academic-enabler skills checklists with students, training them in each of the sub-skills and encouraging them to use the checklists independently to take greater responsibility for their own learning. – Teachers or other observers can use the academic enabler checklists periodically to monitor student progress during interventions--assessing formatively whether the student is using more of the sub-skills. Source: Kazdin, A. E. (1989). Behavior modification in applied settings (4th ed.). Pacific Gove, CA: Brooks/Cole. www.interventioncentral.org 70 Response to Intervention ‘Academic Enabler’ Skills: Sample Observational Checklists www.interventioncentral.org 71 Response to Intervention ‘Academic Enabler’ Skills: Sample Observational Checklists www.interventioncentral.org 72 Response to Intervention ‘Academic Enabler’ Skills: Sample Observational Checklists www.interventioncentral.org 73 Response to Intervention ‘Academic Enabler’ Skills: Sample Observational Checklists www.interventioncentral.org 74 Response to Intervention ‘Academic Enabler’ Skills: Sample Observational Checklists www.interventioncentral.org 75 Response to Intervention ‘Academic Enabler’ Skills: Sample Observational Checklists www.interventioncentral.org 76 Response to Intervention ‘Academic Enabler’ Skills: Sample Observational Checklists www.interventioncentral.org 77 Response to Intervention Activity: Academic Enablers Observational Checklist At your tables: • Review the ‘Academic Enablers’ Observational Checklists. • Discuss how your school might use the existing examples or use the general format to create your own observational checklists. www.interventioncentral.org 78 Response to Intervention Classroom Data Collection • Behavioral Frequency Count/Behavioral Rate. An observer (e.g., the teacher) watches a student’s behavior and keeps a cumulative tally of the number of times that the behavior is observed during a given period. Behaviors that are best measured using frequency counts have clearly observable beginning and end points—and are of relatively short duration. – Examples include: – student call-outs – requests for teacher help during independent seatwork. – raising one’s hand to make a contribution to large-group discussion. Teachers can collect data on the frequency of observed student behaviors: (1) by keeping a cumulative mental tally of the behaviors; (2) by recording behaviors on paper (e.g., as tally marks) as they occur; or (3) using a golf counter or other simple mechanical device to record observed behaviors. www.interventioncentral.org 79 Response to Intervention Behavioral Frequency Count/Behavioral Rate: Example • Example: Ms. Stimson, a fourth-grade teacher, was concerned at the frequency that a student, Alice, frequently requested teacher assistance unnecessarily during independent seatwork. To address this concern, the teacher designed an intervention in which the student would first try several steps on her own to resolve issues or answer her questions before seeking help from the instructor. Prior to starting the intervention, the teacher kept a behavioral frequency count across three days of the number of times that the student approached her desk for help during a daily 20-minute independent seatwork period (baseline). • Ms. Stimson discovered that, on average, the student sought requested help 8 times per period (equivalent to 0.4 requests for help per minute). Ms. Stimson set as an intervention goal that, after 4 weeks of using her self-help strategies, the student’s average rate of requesting help would drop to 1 time per independent seatwork period (equivalent to 0.05 requests for help per minute). www.interventioncentral.org 80 Response to Intervention Classroom Data Collection Rating scales. A scale is developed with one or more items that a rater can use to complete a global rating of a behavior. Often the rating scale is completed at the conclusion of a fixed observation period (e.g., after each class period; at the end of the school day). NOTE: One widely used example of rating scales routinely used in classrooms is the daily behavior report (DBR). The teacher completes a 3- to 4-item rating scale each day evaluating various target student behaviors. A detailed description of DBRs appears on the next page, along with a sample DBR that assesses the student’s interactions with peers, compliance with adult requests, work completion, and attention to task. www.interventioncentral.org 81 Response to Intervention Monitoring Student Academic or General Behaviors: Daily Behavior Report Cards www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Daily Behavior Report Cards (DBRCs) Are… brief forms containing student behavior-rating items. The teacher typically rates the student daily (or even more frequently) on the DBRC. The results can be graphed to document student response to an intervention. www.interventioncentral.org 83 Response to Intervention Daily Behavior Report Cards Can Monitor… • • • • • • Hyperactivity On-Task Behavior (Attention) Work Completion Organization Skills Compliance With Adult Requests Ability to Interact Appropriately With Peers www.interventioncentral.org 84 Response to Intervention Daily Behavior Report Card: Daily Version Jim Blalock Mrs. Williams www.interventioncentral.org May 5 Rm 108 Response to Intervention Daily Behavior Report Card: Weekly Version Jim Blalock Mrs. Williams Rm 108 05 05 07 05 06 07 05 07 07 05 08 07 05 09 07 40 www.interventioncentral.org 0 60 60 50 Response to Intervention Daily Behavior Report Card: Chart www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Rating Scales: Example Example: All of the teachers on a 7th-grade instructional team decided to use a Daily Behavior Report to monitor classroom interventions for Brian, a student who presented challenges of inattention, incomplete work, and occasional non-compliance. They created a DBR with the following items: • Brian focused his attention on teacher instructions, classroom lessons and assigned work. • Brian completed and turned in his assigned class work on time. • Brian spoke respectfully and complied with adult requests without argument or complaint. Each rating items was rated using a 1-9 scale: On average, Brian scored no higher than 3 (‘Never/Seldom’ range) on all rating items in all classrooms (baseline). The team set as an intervention goal that, by the end of a 6-week intervention to be used in all classrooms, Brian would be rated in the 7-9 range (‘Most/All of the Time’) in all classrooms. www.interventioncentral.org 88 Response to Intervention Activity: Daily Behavior Report Card At your tables: • Discuss the Daily Behavior Report Card as a classroom monitoring tool. • How could you use this tool directly or indirectly to measure aspect(s) of student academic concerns? www.interventioncentral.org 89 Response to Intervention Classroom Data Collection • Academic Skills: Cumulative Mastery Log. During academic interventions in which the student is presented with specific items such as math facts or spelling words, the instructor can track the impact of the intervention by recording and dating mastered items in a cumulative log. • To collect baseline information, the instructor reviews all items from the academic-item set with the student, noting which items the student already knows. Then, throughout the intervention, the instructor logs and dates any additional items that the student masters. www.interventioncentral.org 90 Response to Intervention Academic Skills: Cumulative Mastery Log: Example Example: Mrs. Ostrowski, a 1st-grade teacher, decides to provide additional intervention support for Jonah, a student in her class who does not have fluent letter recognition skills. Before starting an intervention, she inventories and records Jonah’s baseline skills—noting that Jonah can fluently and accurately recognize 18 upper-case letters and 14 lower-case letters from the English alphabet. She sets as an intervention goal that Jonah will master all remaining items –8 upper-case and 12 lower-case letters—within four weeks. Mrs. Ostrowski then begins the daily intervention (incremental rehearsal of letters using flashcards). Whenever Jonah is able fluently and accurately to name a previously unknown letter, the teacher records and dates that item in her cumulative mastery log. www.interventioncentral.org 91 Response to Intervention Classroom Data Collection Work Products. Student work products can be collected and evaluated to judge whether the student is incorporating information taught in the course, applying cognitive strategies that they have been taught, or remediating academic delays. Examples of work products are math computation worksheets, journal entries, and written responses to end-of-chapter questions from the course textbook. Whenever teachers collect academic performance data on a student, it is recommended that they also assess the performance of typical peers in the classroom. Work products can be assessed in several ways, depending on the identified student problem. www.interventioncentral.org 92 Response to Intervention Work Products: Example • Example: Mrs. Franchione, a social studies teacher, identified her eighthgrade student, Alexandria, as having difficulty with course content. The student was taught to use question generation as a strategy to better identify the main ideas in her course readings. • Mrs. Franchione decided to assess Alexandria’s student journal entries. Each week, Mrs. Franchione assigned students 5 key vocabulary terms and directed them to answer a social studies essay question while incorporating all 5 terms. She also selected 3 typical students to serve as peer comparisons.. Mrs. Franchione decided to assess Alexandria’s journal entries according to the following criteria: • Presence of weekly assigned vocabulary words in the student essay • Unambiguous, correct use of each assigned vocabulary term in context • Overall quality of the student essay on a scale of 1 (significantly below peers) to 4 (significantly above peers). www.interventioncentral.org 93 Response to Intervention Work Products: Example (cont.) • To establish a baseline before starting the intervention, Mrs. Franchione used the above criteria to evaluate the two most recent journal entries from Alexandria’s journal—and averaged the results: 4 of assigned 5 vocabulary terms used; 2 used correctly in context; essay quality rating of 1.5. • Peer comparison: all 5 assigned vocabulary terms used; 4 used correctly in context; average quality rating of 3.2. Mrs. Franchione set an intervention goal for Alexandria that— by the end of the 5-week intervention period—the student would regularly incorporate all five vocabulary terms into her weekly journal entries, that at least 4 of the five entries would be used correctly in context, and that the student would attain a quality rating score of 3.0 or better on the entries. www.interventioncentral.org 94 Response to Intervention Activity: Work Products At your tables: • Review the form for assessing work products. • Discuss how your school might be able to use this existing form or modify it to ‘standardize’ the collection and evaluation of student work products. www.interventioncentral.org 95 Response to Intervention Classroom Data Collection Behavior Log. Behavior logs are narrative ‘incident reports’ that the teacher records about problem student behaviors. The teacher makes a log entry each time that a behavior is observed. An advantage of behavior logs is that they can provide information about the context within which a behavior occurs.(Disciplinary office referrals are a specialized example of a behavior log.) Behavior logs are most useful for tracking problem behaviors that are serious but do not occur frequently. www.interventioncentral.org 96 Response to Intervention Behavior Log: Example • Example: Mrs. Roland, a 6th-grade Science teacher, had difficulty managing the behavior of a student, Bill. While Bill was often passively non-compliant, he would occasionally escalate, become loudly defiant and confrontational, and then be sent to the principal’s office. Because Mrs. Roland did not fully understand what factors might be triggering these student outbursts, she began to keep a behavior log. She recorded instances when Bill’s behavior would escalate to become confrontational. Mrs. Roland’s behavior logs noted the date and time of each behavioral outburst, its duration and severity, what activity the class was engaged in when Bill’s behavioral outburst occurred, and the disciplinary outcome. After three weeks, she had logged 4 behavioral incidents, establishing a baseline of about 1 incident every 3.75 instructional days. www.interventioncentral.org 97 Response to Intervention Behavior Log: Example (cont.) • Mrs. Roland hypothesized that Bill became confrontational to escape class activities that required him to read aloud within the hearing of his classmates. As an intervention plan, she changed class activities to eliminate public readings, matched Bill to a supportive class ‘buddy’, and also provided Bill with additional intervention in reading comprehension ‘fix up’ skills. Mrs. Roland set as an intervention goal that within 4 weeks Bill’s rate of serious confrontational outbursts would drop to zero. www.interventioncentral.org 98 Response to Intervention Classroom Data Collection Curriculum-Based Measurement. Curriculum-Based Measurement (CBM) is a family of brief, timed measures that assess basic academic skills. CBMs have been developed to assess phonemic awareness, oral reading fluency, number sense, math computation, spelling, written expression and other skills. Among advantages of using CBM for classroom assessment are that these measures are quick and efficient to administer; align with the curriculum of most schools; have good ‘technical adequacy’ as academic assessments; and use standard procedures to prepare materials, administer, and score (Hosp, Hosp & Howell, 2007). www.interventioncentral.org 99 Response to Intervention Description: Worksheet contains either single-skill or multiple-skill problems. CBM Math Computation Administration: Can be administered to groups (e.g., whole class). Students have 2 minutes to complete worksheet. Scoring: Students get credit for each correct digit-a method that is more sensitive to shortterm student gain. www.interventioncentral.org 100 Response to Intervention Curriculum-Based Measurement: Advantages as a Set of Tools to Monitor RTI/Academic Cases • Aligns with curriculum-goals and materials • Is reliable and valid (has ‘technical adequacy’) • Is criterion-referenced: sets specific performance levels for specific tasks • Uses standard procedures to prepare materials, administer, and score • Samples student performance to give objective, observable ‘lowinference’ information about student performance • Has decision rules to help educators to interpret student data and make appropriate instructional decisions • Is efficient to implement in schools (e.g., training can be done quickly; the measures are brief and feasible for classrooms, etc.) • Provides data that can be converted into visual displays for ease of communication Source: Hosp, M.K., Hosp, J. L., & Howell, K. W. (2007). The ABCs of CBM. New York: Guilford. www.interventioncentral.org 101 Response to Intervention Among other areas, CBM Techniques have been developed to assess: • • • • • • • Reading fluency Reading comprehension Math computation Writing Spelling Phonemic awareness skills Early math skills www.interventioncentral.org 102 Response to Intervention Curriculum-Based Measurement: Example Example: Mr. Jackson, a 3rd-grade teacher, decided to use explicit time drills to help his student, Andy, become more fluent in his multiplication math facts. Prior to starting the intervention, Mr. Jackson administered a CBM math computation probe (single-skill probe; multiplication facts from 0 to 12) on three consecutive days. Mr. Jackson used the median, or middle, score from these three assessments as baseline—finding that the student was able to compute an average of 20 correct digits in two minutes. He also set a goal that Andy would increase his computation fluency on multiplication facts by 3 digits per week across the 5-week intervention, resulting in an intervention goal of 35 correct digits. www.interventioncentral.org 103 Response to Intervention Combining Classroom Monitoring Methods • Often, methods of classroom data collection and progress-monitoring can be combined to track a single student problem. • Example: A teacher can use a rubric (checklist) to rate the quality of student work samples. • Example: A teacher may keep a running tally (behavioral frequency count) of student callouts. At the same time, the student may be self-monitoring his rate of callouts on a Daily Behavior Report Card (rating scale). www.interventioncentral.org 104 • Response to Intervention Activity: Classroom Methods of Data Collection Classroom Data Sources: In your teams: Select one of the methods of data collection discussed in • Existing data this section of the workshop that you • Global skill checklist are most interested in having your • Behavioral frequency school adopt or improve. count/behavior rate Discuss how you might promote the • Rating scales use of this data collection method, e.g., • Academic skills: Creating assessment materials for Cumulative mastery log teachers • Work products Arranging for teacher training • Behavior log Having teachers pilot the method and • Curriculum-based provide feedback on how to improve. measurement www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Setting Up Effective Classroom Data Collection www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention The Structure of Data Collection • Teachers can use a wide variety of methods to assess student academic performance or behavior. • However, data collection should be structured to include these elements: baseline, the setting of a goal for improvement, and regular progressmonitoring. • The structure of data collection can be thought of as a glass into which a wide variety of data can be ‘poured’. www.interventioncentral.org 107 Response to Intervention Classroom Data Collection Methods: Examples • • • • • • • • Existing data Global skill checklist Behavioral frequency count/behavior rate Rating scales Academic skills: Cumulative mastery log Work products Behavior log Curriculum-based measurement www.interventioncentral.org 108 Response to Intervention www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Baseline: Defining the Student Starting Point • Baseline data provide the teacher with a snapshot of the student’s academic skills or behavior before the intervention begins. • An estimate of baseline is essential in order to measure at the end of the intervention whether the student made significant progress. • Three to five data-points are often recommended— because student behavior can be variable from day to day. www.interventioncentral.org 112 Response to Intervention Baseline: Using the Median Score If several data points are collected, the middle, or median, score can be used to estimate student performance. Selecting the median can be a good idea when student data is quite variable. www.interventioncentral.org 113 Response to Intervention Baseline: Using the Mean Score If several data points are collected, an average, or mean, score can be calculated by adding up all baseline data and dividing by the number of data points. 13+15+11=39 39 divided by 3=13 Mean = 13 www.interventioncentral.org 114 Response to Intervention www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Intervention ‘Timespan’: How Long is Long Enough? Any intervention should be allowed sufficient time to demonstrate whether it is effective. The limitation on how quickly an intervention can be determined to be ‘effective’ is usually the sensitivity of the measurement tools. As a rule, behavioral interventions tend to show effects more quickly than academic interventions—because academic skills take time to increase, while behavioral change can be quite rapid. A good rule of thumb for classroom interventions it to allow 4-8 instructional weeks to judge the intervention. www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention Performance Goal The outcome goal for an intervention can be estimated in several ways: • If there are research academic norms or local norms available (e.g., DIBELS), these can be useful to set a goal criterion. • The teacher can screen a classroom to determine average performance. • The teacher can select 3-4 ‘typical’ students in the class, administer an academic measure (e.g., curriculum-based measurement writing) to calculate a ‘micro-norm’. • The teacher can rely on ‘expert opinion’ of what is a typical level of student performance. www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention End of Grade 1 SOURCE: Good et al. (2002) DIBELS administration and scoring guide. https://dibels.uoregon.edu/measures/files/admin_and_scoring_6th_ed.pdf www.interventioncentral.org 118 Response to Intervention www.interventioncentral.org Response to Intervention www.interventioncentral.org